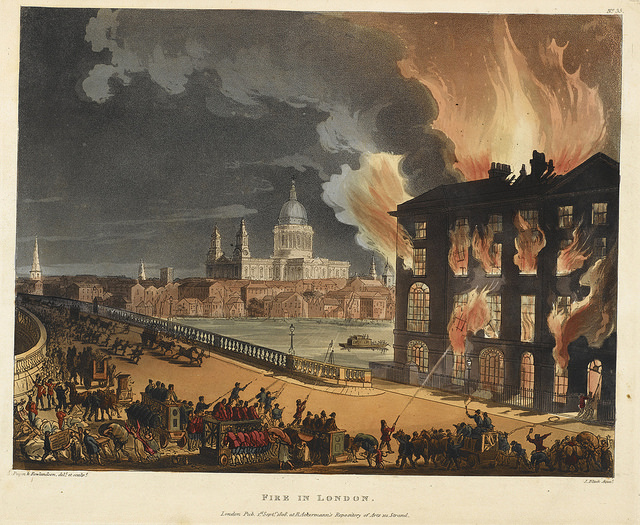

Fire at the Albion Mill, from The Microcosm of London, by William Henry Pyne. R. Ackermann: London, 1808 – 1811

This corn mill was erected by Matthew Boulton, with the backing of City financiers, at the foot of Blackfriars Bridge in 1786. Matthew was an entrepreneur and the business partner of James Watt and the mill provided an ideal opportunity to use their steam engines for grinding the corn and all the associated handling of materials. When erected it was the biggest and best-equipped mill in the country.

The work of construction and erecting the engine was supervised by John Rennie. The first trial of the machinery was made before a great crowd of spectators, including Sir Joseph Banks. There were problems with the sun and planet gear, and the piston rods and other parts of the working gear were defective. Matthew Boulton spent considerable time and effort overcoming the initial difficulties. By April 1786 repairs had been made and the mill was again tested for engine performance. At the beginning of 1789 the second engine with its set of millstones had been laid down.

Each double-acting engine was 50 horse-power and they jointly drove 20 pairs of mill-stones. The engines also hoisted and lowered the corn and flour into and out of the barges, fanned the corn to free it of impurities, and sifted and dressed the meal. Each pair of stones ground nine bushels of corn an hour. So by 1790 the output of the mill was very considerable for the period.

The sales of flour in a week in June 1790 amounted to £6,800, but Boulton was still not satisfied with the state of affairs in respect of finance and organisation. Before he could make any changes, however, the mill was destroyed by fire on 2 March 1791. There were strong suspicions of foul play and Boulton called for a thorough investigation by the government as a matter of national importance. On the other hand, Rennie and Wyatt, the manager of the mill, thought that the fire was caused by accident due to a lack of grease on the large corn machine in front of the kiln.

In many quarters there was great rejoicing at the fire, especially among the mob, rival millers and mealmen discontented by the virtual monopoly of the London flour trade held by the Albion Mill Company. Its efficient production methods had reduced the price of flour and put traditional windmills out of business. The mill was not rebuilt but it was some time before the affairs of the company were wound up. As late as 1800 the erection of a new engine and mill was still under discussion. Finally the ruined building was converted into houses.

Before its destruction the mill was something of a tourist attraction and its roof provided a vantage point for artists wanting to portray London, an example being Robert Barker’s famous panorama. According to Graham Gibberd, the mill was London’s symbol for the impending industrial revolution and its burnt-out shell was the model for William Blake‘s “dark Satanic Mills.” There are extensive records of the mill, including engineers’ drawings, in the Boulton & Watt Archive at Birmingham Central Library.

This article was researched by Richard Woollard.