By Ian Beckwith

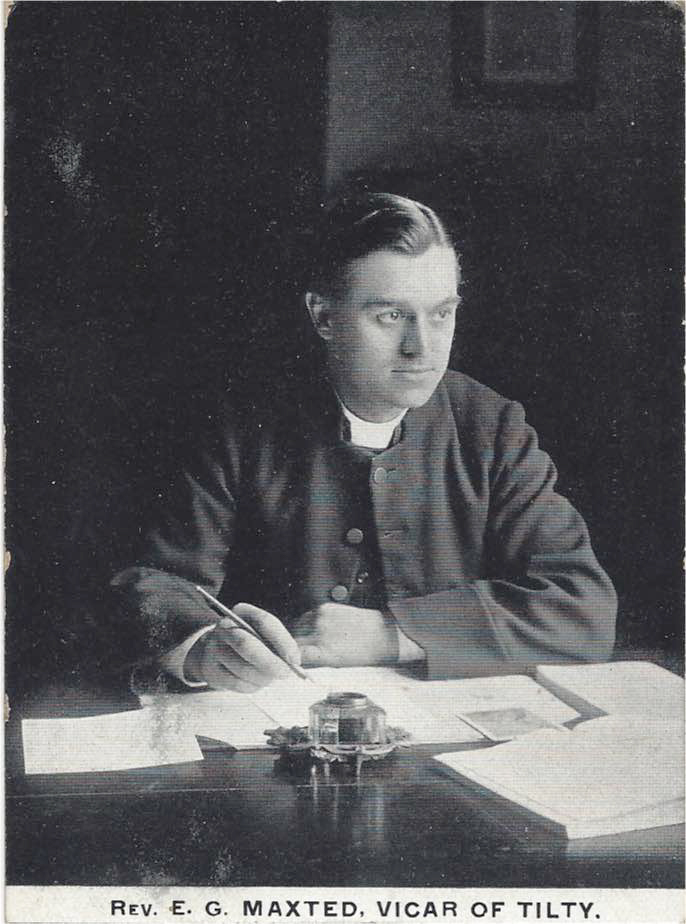

On 5 November 1910, the Essex market town of Great Dunmow held its traditional procession to the bonfire. Led by a brass band, the dummy, perched on a cart pulled by hooded men, moved slowly on its way to immolation. However, the effigy at the centre of the parade was not of Guy Fawkes, the would-be destroyer of Parliament, but of the Reverend Edward George Maxted, the priest of Tilty, a small parish, four miles away.

What had the Reverend Maxted done to arouse so much animosity? Answer: the gospel he preached was not exclusively the Christian one but the unadulterated gospel of socialism. What is more, he had vowed to convert the Tory heathen of Dunmow to his way, the socialist way.

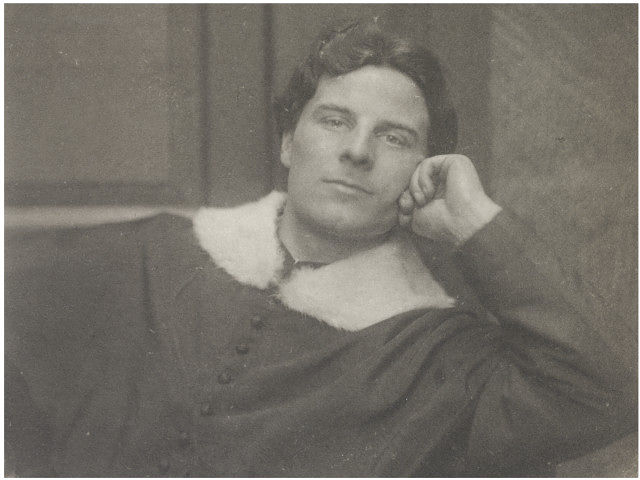

Maxted, like the infamous ‘Red Vicar’ of Thaxted Conrad Noel (1869–1942), was appointed by the socialite-turned-socialist, Frances Evelyn ‘Daisy’ Greville, Countess of Warwick (1861–1938),[1]Née Maynard. She was the inspiration behind the popular song Daisy, Daisy (Give me your answer do). who owned most of this corner of north-west Essex in her own right. But whereas Conrad Noel came from the same aristocratic background as his patron (he was the grandson of an earl), Edward Maxted was cut from another cloth altogether.

Born in 1874, the son of a Kent tinsmith, Maxted trained as an ironworker, before, aged seventeen, he felt called to the priesthood. In order to save enough money to put himself through college, he went to Toronto, Canada, where he met his future wife, Sallester Ramage, the daughter of a Thames lighterman who had migrated to Canada. After four years, Edward returned to England and enrolled on a course at King’s College, London, graduating with a first-class qualification in theology, and was ordained deacon by the bishop of Rochester in 1901.[2]Deacon: the first stage in becoming a priest, usually lasting a year, during which he could perform baptisms and funerals, and lead all services except the Mass. The Anglican diocese of Southwark was … Continue reading

Maxted was that almost unique figure: a working-class parson in a church whose clergy were normally Oxbridge graduates and always from the upper end of the social spectrum. The function of the Church of England, it has been said, ‘was to place a civilizing influence in the form of an educated gentleman in every parish in the Kingdom’[3]Marrin, A., The Last Crusade: The Church of England in the First World War. Duke University Press, 1974, p.12. and its clergy have been likened to colonial governors, their role being to keep the ‘natives’ quiet. The problem was that the ‘natives’ wanted him to behave like the colonial governors they were familiar with and when he refused, they turned on him. Conrad Noel, with his patrician air, his ‘matinee idol’ looks, his persona as an educated gentleman, coupled with his sense of theatre, while not without enemies, not only managed to survive as the Red Vicar but would actually become fondly remembered as a legend in his own lifetime. Edward Maxted, by contrast, stuck out like the proverbial sore thumb. Obviously not a gentleman, he probably did not even speak Received Pronunciation English, and his wife also had working-class origins.

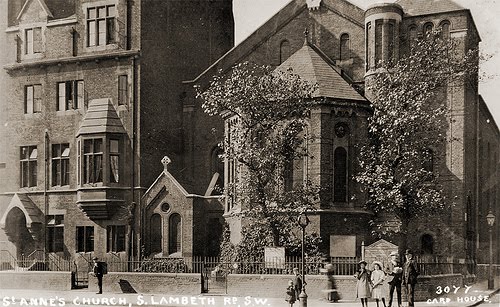

In ecclesiastical jargon, Edward Maxted served his title as curate at Christ Church, Battersea from 1901 to 1904. Later, he would claim that as a boy he had dreamed of playing a role similar to John Ball, the itinerant priest and leader in the fourteenth-century Peasants’ Revolt.[4]John Ball (born c. 1338), whose radical preachings preceded Wycliffe by ten years, was hanged, drawn and quartered at Coventry in 1381. At seventeen, probably during his time in Canada, Maxted bought a copy of Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward. In 1913 Edward Maxted claimed to have been brought to socialism twenty years earlier, i.e. in 1893, the year in which he arrived in Toronto. Perhaps it was then that he had purchased his copy of Looking Backwards. Published in the USA in 1888 and in the UK in 1890, Looking Backward was, after Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Ben Hur, the third best-seller of its day, its British edition selling over 250,000 copies. Written against a background of economic recession and social unrest in the United States, the novel gave a vision of a utopian society in which, although socialism was not mentioned, the means of production and distribution had been nationalised. Whenever he was called on to explain what socialism meant, Maxted offered essentially a version of Bellamy’s utopian vision. Later he would say that the demands of preparing for holy orders meant that he gave socialism no more thought until, on the first Sunday of his first curacy at Christ Church, Battersea, he encountered a socialist meeting. He then read every book on socialism in Battersea Public Library and ‘took up’ with the socialist weekly The Clarion. However, he could not, he claimed, take an active part in socialism until, in 1904, he moved to St Anne’s Church on South Lambeth Road.[5]He made this remark in his ‘apologia’, The Trials and Troubles of a Socialist Vicar by Rev E.G. Maxted, Vicar of Tilty, October 1909. Hull University Library DNO 6/8.

St Anne’s was a relatively new ‘very large, very poor’ parish, and it had a history of appointing socialist clergy. The liturgist Percy Dearmer (1867–1936), was served his first curacy there. Best known for his later collaboration with Ralph Vaughan Williams and Martin Shaw on The English Hymnal and The Oxford Book of Carols, Dearmer was secretary of the Christian Socialist Union. In December 1893 Dearmer’s wife Jessie Mabel Pritchard White was appealing for second-hand clothes and other old articles for ‘a Jumble Fair’. ‘Will some country clergy help the hard battle [i.e. against poverty] which South London churchmen are fighting in the same Diocese?’ asked The Surrey Mirror on 3 December 1893.[6]Mabel died of typhus while serving with an ambulance unit in Serbia in 1915. Its second vicar, William Morris, ‘seemed to know every man, woman and child… He is the most practical, self-denying of socialists and has given away all that he had to help the poor’.

Morris deserves an article all to himself. Son of a wealthy Liverpool insurance broker Thomas Morris, of Elmhurst, near Liverpool, William Alexander Morris graduated with a third-class degree in 1880 and was deaconed in that year. Formerly curate of St Peter’s, Vauxhall, where he was known as ‘the gas workers’ parson’ for the strong support that he gave to the gas workers in Vauxhall during their strike in 1889, including a Boxing Night party for six hundred gas workers and their wives in the Vauxhall Working Men’s Club, paid for out of the curate’s own pocket, so reported Reynolds News on 29 December 1889. He became vicar of St Anne’s in 1891. During Morris’s incumbency, St Anne’s became a centre of Christian Socialism, ‘combined’, according to the South Wales Daily News of 26 September 1893, ‘with ritualistic practice’. The Fabian Society, a socialist organisation founded in 1884 whose purpose is to advance the principles of democratic socialism, met regularly at St Anne’s, as did the Guild of St Matthew, founded by the Rev Stewart Headlam in 1877. The Guild’s aims were ‘to promote the study of social and political questions in the light of the Incarnation’.[7]For a discussion of Headlam’s complex theology, see Orens, J., The Mass, The Masses, and the Music Hall: Stewart Headlam’s Radical Anglicanism, Jubilee Group, St Matthew’s Rectory E2 6EX, Jan … Continue reading Preaching at the Guild Festival at St Anne’s, in 1893, Morris called on the members to do their best ‘to make the poor discontented with their lot and the rich discontented with themselves’. [8]South Wales Daily News, 25 September 1893. In 1903 Morris retired due to exhaustion and died early in the following year.[9]The London Daily News of 6 February 1904 reported that his funeral was attended by a large turn-out of gas workers, as well as by members of the Guild of St Matthew, the Fabian Society, the MPs John … Continue reading He was described as a ‘fine specimen of a muscular parson’ for his work at St Anne’s; in his rural Essex parish Edward Maxted would set a different example of muscular Christianity.

In February 1906, while curate at St Anne’s, South Lambeth Edward Maxted addressed a rally of the unemployed in Hyde Park, arguing that socialism was the only solution to the problem of unemployment.

After three years at St Anne’s, Maxted moved to St Andrew’s, Battersea, where his political activities caused such unrest that he was asked to resign. No doubt speaking at socialist meetings, without his vicar’s permission was a factor. On Sunday 6 October 1907 Maxted spoke on ‘Socialism and the Universities’ at the Chandos Hall, in Stratford, East London. The next day, under the headline ‘Curate’s Night Out’, The Hull Daily Mail reported that, following the ‘Socialist hymn’, Arise England, ‘Our comrade Maxted’ was called upon to speak. ‘Attired in orthodox Church of England dress, he began: “I am here tonight”, he explained, “by the kindness of my vicar. I asked him for a night off, but I took particular care not to say where I was going. If I had said I was coming here, he would not, in all probability, have given me leave…”. He continued: “I am absent tonight from my clerical duties but I wish I could spend every Sunday evening, aye, and every Sunday morning in preaching Socialism.”’ He then made what was described as a violent speech in favour of socialism. “What we want to see is State ownership in education right from the primary school up to the universities.” Justice, the weekly newspaper of the SDF [what is this?], shows that, during 1907, Edward Maxted was one of the speakers touring London with the Clarion van.[10]The Clarion pioneered the use of vans which toured small towns and villages throughout England and Scotland from 1896 until 1929, spreading the socialist message.

Maxted’s next appointment was to St Lawrence’s in Catford, south-east London, given on condition that he said nothing about socialism. The fact that he had up to this point served as curate in four separate parishes over a period of seven years suggests that the incumbents of those parishes each had doubts about him. However, in 1908 the incumbent of Tilty, died.[11]The Chelmsford Chronicle, 31 Jan 1908. Formerly a priest in London’s East End, the Rev Stephenson was said to be a quiet, retiring man – in sharp contrast to his successor. After, as he put it, three months of holding his tongue, Maxted was instituted as vicar. From ministering to populations of between 10,000 and 15,000 in the city, Maxted now found himself looking after 242 people spread across 1000 rural acres.[12]The 1911 Census shows that farming was the main source of employment in the parish. Apart from two dressmakers, a grocer and dealer, two bricklayers, a coal yard foreman, two coach builders, and … Continue reading In Maxted’s own words, ‘… if you can only find it, it is rather scattered and consists mainly of fields.’[13]Maxted, E., The Trials and Troubles of a Socialist Vicar by Rev E. G. Maxted, Vicar of Tilty, Oct 1909. Hull University Library DNO 6/8, first published in The Clarion.The report of Maxted’s induction, on 11 May 1908, described him as one of the few socialist clergy of the Church of England who has taken a public part in propaganda for the spread of socialism. ‘A quiet earnest man… He has a peculiar [sic] experience among the working class population in London’.[14]Essex Newsman, 16 May 1908. The Chelmsford Chronicle (12 Feb 1909) observed that the Rev Maxted had been obliged to leave his London curacy in consequence of his advocacy of socialism.

Edward Maxted probably came to the Countess of Warwick’s attention as a result of ‘A Socialist demonstration… at Dunmow’ on Saturday 2 June 1906, ‘the first meeting of the kind ever held in the old Essex town’, when ‘a number of the confraternity’, most of them wearing red ties and long hair, many arriving on bicycles, assembled at the Countess’s Essex home in Easton Lodge park over the Whit weekend.[15]Chelmsford Chronicle, 9 Jun 1906. Among the speakers attempting ‘to convert Dunmow to Socialism’ was ‘the Revd H [sic] Maxted, clergyman of the Church of England’. All were met with hostility.[16]Cheltenham Chronicle, 9 Jun 1906. According to the Cheltenham Chronicle, over 200 socialists took over Easton Park, where they were accommodated in the great pavilion adjoining the Countess’s … Continue reading

Soon after his institution at Tilty, reports began to appear concerning Maxted’s extra-parochial activities[17]Essex Newsman, 26 Sep 1908. It should be borne in mind that what is known of Edward Maxted’s activities and speeches relies entirely on press reports. In September 1908 he was the main speaker at the Braintree and Bocking Independent Labour Party. According to the chairman, socialists had been called atheists, causing much abuse, but the presence of a Church of England clergyman should ‘disperse’ such a view. Maxted set forth what would become familiar tropes. All agreed that there was something rotten in the state of the country. The only remedy was socialism. Socialism meant the common ownership, by the public, of the means of production and exchange. Just as now, people went to Parliament thinking that they represented the public, so, under socialism people would be elected to manage all the affairs of life – all the land and the means of making goods, all the capital and machinery in workshops. Socialism would become a scheme of society, perfect and complete in all its parts. Socialists took their stand at the head of the stream of human progress.

People laughed at socialism, Maxted continued, but it was remarkable that where it had been applied it was the work of solid old Conservatives or Liberals, when common sense without prejudice had been allowed its way. The Balfour Education Act, which abolished school boards and placed elementary education under the control of county and county borough councils, provided for secondary and technical education and encouraged county councils to subsidise existing grammar schools and provide new ones, might be regarded as a piece of socialist legislation.[18]Education Act, 1902, drafted by A. J. Balfour. The purchase of the South London Tramways by London County Council in 1900 was a good illustration of the central principle of socialism in action, as was the provision of public waterways and public schools. Moreover, the day of voluntary effort in education was over: all schools would have to be owned by the State; the only question was one of terms. All branches of education would be paid for out of taxation. A Ministry of Food would arrange for the loaves of bread, which all the people would require. This would entail State ownership of land, railways and of all the factories. When every single thing that was necessary to the people became publicly owned, ‘then Socialism would be in perfection’.

This was the utopian vision which, for six years, Edward Maxted, persisted in holding up before the people of Dunmow and its hinterland, mainly in weekly, crowded, open air meetings on the village green during the summer, against a background of barracking, predictably from the local farmers but, more surprisingly, the farm workers too, and despite actual physical attacks (to which he responded in kind, rolling up his sleeves and daring any man to strike him). Maxted later confirmed to a newspaper reporter that he had been threatened with tarring and feathering and when he replied that he was ready, he had been told that it would mean lead for him, from a gun.

Even his patroness, the Countess, seems to have wearied of him, possibly because he campaigned for the improvement of the farmworkers’ cottages on her estate. He also stood for Essex County Council, coming a creditable second to his Tory rival.[19]His opponents were Lancelot Cranmer Byng (1872–1945), of Folly Mill, Thaxted, ‘soldier, traveller and oriental scholar’, ‘a dabbler in prose and verse’, a Tory and JP, ‘tall, spare, … Continue reading

Despite his radicalism, the pugnacious vicar of Tilty and Mrs Maxted often hobnobbed with the great and the good. He, together with various leading figures in Dunmow, formed the Committee organising the Easton Lodge Flower Show in August 1911. In the same month, the Rev and Mrs Maxted were at Easton Lodge for a display of Morris dancing led by Cecil Sharpe, the folk song collector, musician, composer and Fabian socialist, organised by the Rev and Mrs Conrad Noel, and hosted by the Earl and Countess of Warwick, at which the local élite were also present.[20]Chelmsford Chronicle, 5 May 1911.

Perhaps his finest hour came in the late summer of 1914. A few weeks before the outbreak of war the farm workers of his part of Essex struck for higher wages and the right to join a union. There was a certain amount of violence, the farmers used the tactic of lock-out, and Edward Maxted took time out to cycle or drive round the district encouraging the strikers. The farmers were panicking as harvest time drew closer. They were saved on 28 June when Gavril Princip assassinated the Crown Prince Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo. The strikers responded to the call to do their patriotic duty and got on with the harvest. Soon many would respond to the call to arms, their names to be written, cheek by jowl with the sons of farmers and squires, in letters of blood on the war memorials of the villages where only recently a battle of a different sort had been fought between worker and farmer.[21]Even in death local hierarchy persisted, the names of the officers being inscribed separately from other ranks. For an account of the Agricultural Strike of 1914, see Brazier, R., The Empty Fields, … Continue reading

As for Edward Maxted, he fell silent. There were no more meetings on the village green, no more promises of the earthly paradise which would be achieved when everyone embraced socialism, and no more Guy Fawkes Nights when he was burned in effigy. Had his vision been turned to dust and ashes by the war? It is possible that he was a pacifist, but there is not enough evidence to be sure.

By 1915 The Chelmsford Chronicle was waxing nostalgic: ‘Those who remember the stormy scenes which occurred in the Dunmow district when the Rev E.G. Maxted set out first on his mission “to convert Dunmow to Socialism” are not a little surprised at the present placid attitude everywhere observant.’ Where once the Dunmow audience had been shocked at the implication that the vicar endorsed the views of Karl Marx in favour of free love and polygamy – not that Maxted had ever referred to such issues – now ‘the polygamy question was being discussed as an after-effect of the War’.[22]Chelmsford Chronicle, 26 Mar 1915. Maxted confined himself to a letter to the paper, protesting at a proposal to take boys aged twelve out of school and put them to work on farms to replace the men who had gone to the Front.[23]Chelmsford Chronicle, 19 Mar 1915. In July 1915, as part of the Day of National Intercession, he and the vicar of Dunmow spoke at open-air meetings on the same village green where in former times he had fought his good fight for socialism.[24]Essex Newsman, 17 Jul 1915. A year later, coinciding with the start of the Battle of the Somme, Maxted wrote, unsuccessfully, seeking exemption from conscription of his forty-year-old gardener and grave-digger.[25]Chelmsford Chronicle, 14 Jul 1916. In November 1917 he reported that as a wartime economy his household had dispensed with the services of a maid.

In 1918 Edward Maxted left Tllty in an exchange of parishes with a vicar in Bristol. Barely two years later, The Western Daily Press advertised the contents of St Aidan’s Vicarage, Bristol, to be sold by auction on 30 January, on the instructions of the Rev E. G. Maxted, who was sailing for New Zealand. Two days before the auction, leaving behind all their possessions, Maxted, Sallester and their four children sailed from Liverpool, the passenger manifest listing Maxted’s occupation as ‘farmer’.[26]Western Daily Press, 29 Jan 1920. The contents of the vicarage, as listed in the advertisement, appear lavish. They include, besides the beds and bedding, a walnut bedroom suite, a stained … Continue reading The family landed in Canada on 12 February 1920. Now described as ‘clerk in holy orders’. The Maxteds left Vancouver two months later but after just over a year in New Zealand, they returned to Canada. On 21 April 1922 the family travelled to St Andrew’s Episcopal Church, in Barberton, Ohio in the United States.[27]The Episcopal Church of the United States (ECUSA) is the US branch of the world-wide Anglican Communion. The parish records show that he was priest there from 1922 to 1923. Thereafter he served as a parish priest in Pascagoula, Mississippi, becoming a United States citizen in 1933, renouncing for ever all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty and in particular to George V, King of Great Britain ‘to whom I am now subject’. He died on 7 September 1966, in Houston, Texas, aged ninety-two.[28]His wife Sallester predeceased him by six years. Of their four children, godchildren of an English countess, one son fought in the US Army, achieving the rank of master sergeant, another became … Continue reading

What evidence there is of Maxted’s theology suggests that it had little to do with Christian Socialism, not even in his 1909 ‘apologia’, The Trials and Troubles of a Socialist Vicar. His indebtedness to Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backwards is evident in the reports of his speeches, prior to 1910. In September 1910 he said that he wanted ‘first to establish the Kingdom of God on earth, and Socialism was the only way to do that’. He appears never to have alluded to the key tropes of Christian Socialist theology: the Fatherhood of God with its corollary, the Brother/Sisterhood of humanity, which was the foundation of Christian Socialism. Maxted made no explicit reference to Incarnation theology, summed up thus by Henry Scott Holland: ‘If we believe in the Incarnation, then we certainly believe in the entry of God into the very thick of human affairs’. Nor, apparently, did Maxted, in his public speeches, quote another important Christian Socialist text, the Sermon on the Mount. He referred occasionally to what he called the Hebrew land law, i.e. that God had given the land for the use of all.

His main concern seems to have been to prove the compatibility of socialism and Christianity, claiming that socialism was Christianity applied to industrial concerns and if Christians would think out their Christianity they would become socialists. It is significant that the visitors who spoke at Maxted’s open air meetings, came mostly from the secular socialist societies – the Independent Labour Party, the Socialist Democratic Federation, the Essex Socialist Federation – while the local societies he spoke to, such as the Chelmsford Socialist Society, were secular, and only occasionally gatherings organised by the local churches. In fact his neighbours among the clergy, including Conrad Noel, clearly found him an embarrassment.

Whereas ‘Noel did not see himself as a revolutionary leader in the political sense’, seeking, at Thaxted, rather to recreate an imagined pre-Reformation ‘Merrie England’, Edward Maxted did. There is a sense in which, in the way he proclaimed socialism, Edward Maxted set aside his priestly role. When, after he had been physically attacked, having told The Chelmsford Chronicle that if he caught one of his assailants he ‘”would hit him as hard as he could, then seize him by the throat and roll on the ground with him”’, Maxted was asked whether a more peaceful approach might be more effective, he replied that the doctrine of turning the other cheek or non-resistance was all very well in some cases but not at the kind of meetings he held. Conrad Noel wrote that his arrival in Thaxted had not been made easy ‘by the preaching of a neighbouring Socialist vicar… he [had] held a meeting and infuriated the people, not so much by his Socialism as by his way of presenting his message’. Nevertheless these words of Noel’s may stand as Edward Maxted’s epitaph: he was, Noel said ‘one of the few clergy who was loyal to the Church [whereas] those clergy who are not keen about bringing the Kingdom of God on earth but are merely waiting to go to Heaven when they die are traitors to their Church and religion’.

Ian Beckwith graduated from Nottingham University in 1958 and retired as a country vicar. He taught history in state grammar schools before becoming Lecturer in Local History at Bishop Grosseteste College of Education (BGCE), Lincoln. He also taught Local History courses for Nottingham and Hull University Adult Education Departments. His histories of Lincoln and Gainsborough were published by Barracuda Press and he has contributed articles to, among others, History Today, The Journal of Ecclesiastical History, and The Journal of Agricultural History. From 1979 to 1982 he was Director of the Centre for the Study of Rural Society at BGCE. After early retirement in 1984, he taught for the OU Southern Region and Oxford University Department of Continuing Education. He subsequently graduated with a Master’s degree in Theology from Oxford University and ended his full-time working life as a country vicar. He now lives in a second retirement, in Shropshire, in a converted watermill at the foot of Wenlock Edge, where, thanks to the internet, he is happily occupied with historical research.

References

| ↑1 | Née Maynard. She was the inspiration behind the popular song Daisy, Daisy (Give me your answer do). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Deacon: the first stage in becoming a priest, usually lasting a year, during which he could perform baptisms and funerals, and lead all services except the Mass. The Anglican diocese of Southwark was not founded until 1905. Until then, parishes south of the Thames were part of the diocese of Rochester. |

| ↑3 | Marrin, A., The Last Crusade: The Church of England in the First World War. Duke University Press, 1974, p.12. |

| ↑4 | John Ball (born c. 1338), whose radical preachings preceded Wycliffe by ten years, was hanged, drawn and quartered at Coventry in 1381. |

| ↑5 | He made this remark in his ‘apologia’, The Trials and Troubles of a Socialist Vicar by Rev E.G. Maxted, Vicar of Tilty, October 1909. Hull University Library DNO 6/8. |

| ↑6 | Mabel died of typhus while serving with an ambulance unit in Serbia in 1915. |

| ↑7 | For a discussion of Headlam’s complex theology, see Orens, J., The Mass, The Masses, and the Music Hall: Stewart Headlam’s Radical Anglicanism, Jubilee Group, St Matthew’s Rectory E2 6EX, Jan 1979. |

| ↑8 | South Wales Daily News, 25 September 1893. |

| ↑9 | The London Daily News of 6 February 1904 reported that his funeral was attended by a large turn-out of gas workers, as well as by members of the Guild of St Matthew, the Fabian Society, the MPs John Burns and Sir Federick Cook, Will Thorne, one of the founders of the Gas Workers’ Union, together with representatives from various trades unions and labour and church societies. Will Thorne had also been one of the organisers of the Dock Strike in 1889. |

| ↑10 | The Clarion pioneered the use of vans which toured small towns and villages throughout England and Scotland from 1896 until 1929, spreading the socialist message. |

| ↑11 | The Chelmsford Chronicle, 31 Jan 1908. |

| ↑12 | The 1911 Census shows that farming was the main source of employment in the parish. Apart from two dressmakers, a grocer and dealer, two bricklayers, a coal yard foreman, two coach builders, and two road menders, there were 11 farmers and 52 farm workers. The latter included three women in their seventies. Thus just over 26 per cent of the total population was engaged in agriculture. |

| ↑13 | Maxted, E., The Trials and Troubles of a Socialist Vicar by Rev E. G. Maxted, Vicar of Tilty, Oct 1909. Hull University Library DNO 6/8, first published in The Clarion. |

| ↑14 | Essex Newsman, 16 May 1908. The Chelmsford Chronicle (12 Feb 1909) observed that the Rev Maxted had been obliged to leave his London curacy in consequence of his advocacy of socialism. |

| ↑15 | Chelmsford Chronicle, 9 Jun 1906. |

| ↑16 | Cheltenham Chronicle, 9 Jun 1906. According to the Cheltenham Chronicle, over 200 socialists took over Easton Park, where they were accommodated in the great pavilion adjoining the Countess’s mansion. |

| ↑17 | Essex Newsman, 26 Sep 1908. It should be borne in mind that what is known of Edward Maxted’s activities and speeches relies entirely on press reports. |

| ↑18 | Education Act, 1902, drafted by A. J. Balfour. |

| ↑19 | His opponents were Lancelot Cranmer Byng (1872–1945), of Folly Mill, Thaxted, ‘soldier, traveller and oriental scholar’, ‘a dabbler in prose and verse’, a Tory and JP, ‘tall, spare, walrus-moustached’, he lived as a sort of minor squire (Groves, R., Conrad Noel and the Thaxted Movement, p.64), and Colonel S.D. Rainsford (1853–1920), of Pond House, Boxted, late Royal Artillery. The Thaxted Division was long and narrow, ‘so that those at one end know nothing of those at the other’. The electorate numbered 1,825. |

| ↑20 | Chelmsford Chronicle, 5 May 1911. |

| ↑21 | Even in death local hierarchy persisted, the names of the officers being inscribed separately from other ranks. For an account of the Agricultural Strike of 1914, see Brazier, R., The Empty Fields, Ian Henry Publications, 1989. |

| ↑22 | Chelmsford Chronicle, 26 Mar 1915. |

| ↑23 | Chelmsford Chronicle, 19 Mar 1915. |

| ↑24 | Essex Newsman, 17 Jul 1915. |

| ↑25 | Chelmsford Chronicle, 14 Jul 1916. |

| ↑26 | Western Daily Press, 29 Jan 1920. The contents of the vicarage, as listed in the advertisement, appear lavish. They include, besides the beds and bedding, a walnut bedroom suite, a stained dining table and six walnut dining room chairs, a five foot walnut sideboard, overmantle and pier glasses, a hand sewing machine, marble clock, a cottage piano with burr walnut case by Barrett & Robinson, an Edison phonograph and records, occasional tables and chairs, a small walnut bureau, a Chesterfield settee, several hundred volumes of books, carpets, rugs, pictures, gas fires, china and glass, kitchen furniture and utensils, a carpet sweeper, two gents’, one lady’s and one juvenile’s bicycles, a rocking horse and lawn mower. |

| ↑27 | The Episcopal Church of the United States (ECUSA) is the US branch of the world-wide Anglican Communion. |

| ↑28 | His wife Sallester predeceased him by six years. Of their four children, godchildren of an English countess, one son fought in the US Army, achieving the rank of master sergeant, another became a bookkeeper, the third an Episcopalian priest; their daughter married a Canadian chauffeur and lived in Toronto. |