The Sowerby family is without equal in the history of natural history for the depth and variety of its contribution to science. Fourteen members of the family published, wrote or illustrated natural history works between about 1780 and 1954. Subjects covered included botany, zoology, conchology, palaeontology and mineralogy. They worked with and for most of the great names in 19th-century natural history, and the family correspondence is an unparalleled source of biographical, bibliographical and historical information. The founder of this dynasty, James Sowerby, was closely connected to Lambeth.

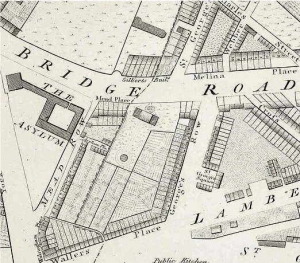

James Sowerby was born on 21 March 1757, in the City of London; he died at No. 2-3 Mead Place, Lambeth, on 25 October 1822. He was the son of John Sowerby, a carver of inscriptions, and his wife Arabella Goodspeed.

James studied art at the Royal Academy in London and began making studies of wildflowers and plants to include in his miniature portraits. This led to an association with William Curtis (1746-1799), botanist and author of Flora Londinensis. Curtis taught him how best to depict plants and their blossoms. James hand-coloured many of the plates for this publication as well as doing the original copper engravings for a number of them. He also painted the only known view of William Curtis’s Lambeth Botanic Garden.

At the Royal Academy James became friendly with a fellow student, Robert De Carle whose sister, Anne Brettingham De Carle, he later married. In 1786 they moved into the house in Mead Place, a gift of the bride’s father. The house was close to the present Morley College in Westminster Bridge Road and survived until bombed in the Second World War. His two eldest sons, James De Carle (1787-1871) and George Brettingham (1788-1854), were also artists and naturalists and did substantial original work; and they completed much that was begun by their father.

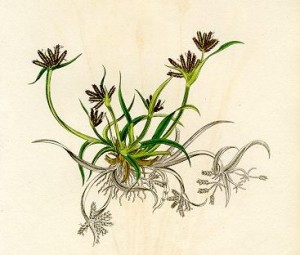

In 1790 James Sowerby started the first of his own illustrated works: English Botany: or Coloured Figures of British Plants, With Their Essential Characters, Synonyms, and Places of Growth (1790-1814). This subsequently became known as ‘Sowerby’s Botany’, although the text was supplied anonymously by Sir James Edward Smith. His accurate descriptions and Sowerby’s beautifully coloured drawings made it a highly esteemed work which was frequently republished. It was issued in 36 volumes over 23 years and contained 2,592 hand-coloured plates of British plants.

Sowerby’s second most important publication, Mineral Conchology of Great Britain, or Coloured Figures and Descriptions of those Remains of Testaceous Animals, or Shells which have been Preserved at Various Times, and Depths in the Earth (London 1812-1846), is actually a work of invertebrate paleontology (a term that had not yet come into use in Sowerby’s day) and it recorded, for the first time, many index fossils found in England. This work, too, was issued in parts, over a 34-year period (the final parts were produced by James De Carle with the help of George Brettingham).

Sowerby also provided illustrations for other natural history works, such as that of Strata Identified by Organized Fossils by William Smith. But probably his major contribution to natural history was his vast correspondence with naturalists in Britain and abroad: many specimens were sent to him for identification. He too sent others in return, together with copies of parts of his publications, stimulating further research.

Sowerby supplied the plates for many other scientific works. He also developed a theory of colour which he dedicated to “the great Isaac Newton”: A New Elucidation of Colours, Original Prismatic and Material: Showing Their Concordance in the Three Primitives, Yellow, Red and Blue: and the Means of Producing, Measuring and Mixing Them: with some Observations on the Accuracy of Sir Isaac Newton (1809). Sowerby set himself two tasks with this work: he wished to re-emphasise the significance of brightness and darkness, which after Newton had fallen into obscurity; and he wished to clarify the difference which exists between colours. Sowerby assumes the existence of three basic colours, red, yellow and blue (he actually selects gamboge – a poisonous yellow sap from Asiatic plants – carmine and Prussian blue, which are then combined). He attempted to transform Newton’s seven primary colours into three materially renderable basic colours. This work attracted the attention of the painter J.M.W. Turner with whom he was acquainted.

The accumulated specimens that Sowerby used in his works took on, more and more, the appearance of a museum, and in 1796 he was obliged to add a room to the rear of his house in which to store them. It was Sowerby’s plan to have, eventually, a complete collection of the natural history of Great Britain. He described his “museum” as “some thousands of minerals, many not known elsewhere, a great variety of fossils, most of the plants of English Botany about 500 preserved specimens or models of fungi, quadrupeds, birds, insects, &c. all the natural production of Great Britain.” In a printed prospectus of 1821 Sowerby reminded the public that “a fire is kept in the Museum every Tuesday during the winter; from eleven o’clock ’til four.”

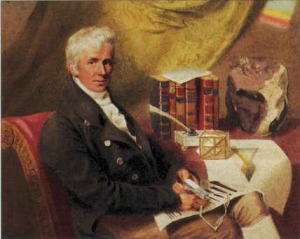

One of the star exhibits in the museum was a meteorite that landed in Yorkshire in 1795. This was later purchased by the British Museum and is now known as the “Wold cottage chondrite”. This meteorite dominates the 1816 watercolour portrait of Sowerby by James Heaphy where he is seen seated next to his books. This meteorite shrunk over time as Sowerby used to chop bits off to send to interested correspondents.

His original plan of creating a major public institution was attempted by his sons. Indeed, James de Carle Sowerby (1787-1871) who carried on living there until 1831 was eminently capable of following in his father’s footsteps. He was a friend of Michael Faraday (1791-1867) and he studied under Sir Humphrey Davy (1778-1829). His knowledge of chemistry led him to propose a classification of minerals according to their chemical composition, and to this end he analyzed many specimens published in British Mineralogy and Exotic Mineralogy. J. de C. Sowerby helped found the Royal Botanic Society and was its secretary for 30 years.

A notice in Mineral Conchology printed in 1827 stated that “tickets for admission to study in Sowerby’s Museum and Library may be had at 10s each for three months, or £2 per annum.” It should be kept in mind that Sowerby’s “Museum” always sounded more formal when it was referred to in print than it was in fact. The attempt to keep the museum functioning did not in fact last very long after the original Sowerby’s death and the collection was auctioned off in 1831; much of it was purchased by the Natural History Museum. There is a large collection of all the family’s papers at this museum.

This article was researched by Richard Woollard

References

Colour theory www.colorsystem.com

Mineralogy www.lhconklin.com