by Ken MacTaggart FBIS

A unique collection of unusual art adorns the walls of the British Interplanetary Society’s headquarters in South Lambeth Road.

The striking building of yellow Georgian brick near Vauxhall Park, at the corner of Langley Lane, is a familiar sight to passers-by rushing to and from Vauxhall station. But few have stepped under the fanlight window and through the heavy wooden door of what cab drivers call the ‘Space Station’.

Inside are offices, presentation rooms for the Society’s conferences, its comprehensive library and the imposing Council Room. Around the long polished 12-seater table hang souvenirs of Britain’s early pioneers of rocketry and space flight, including many examples of the extraordinary art of Ralph Smith.

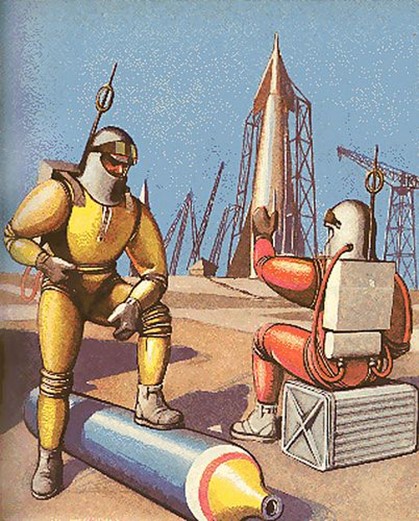

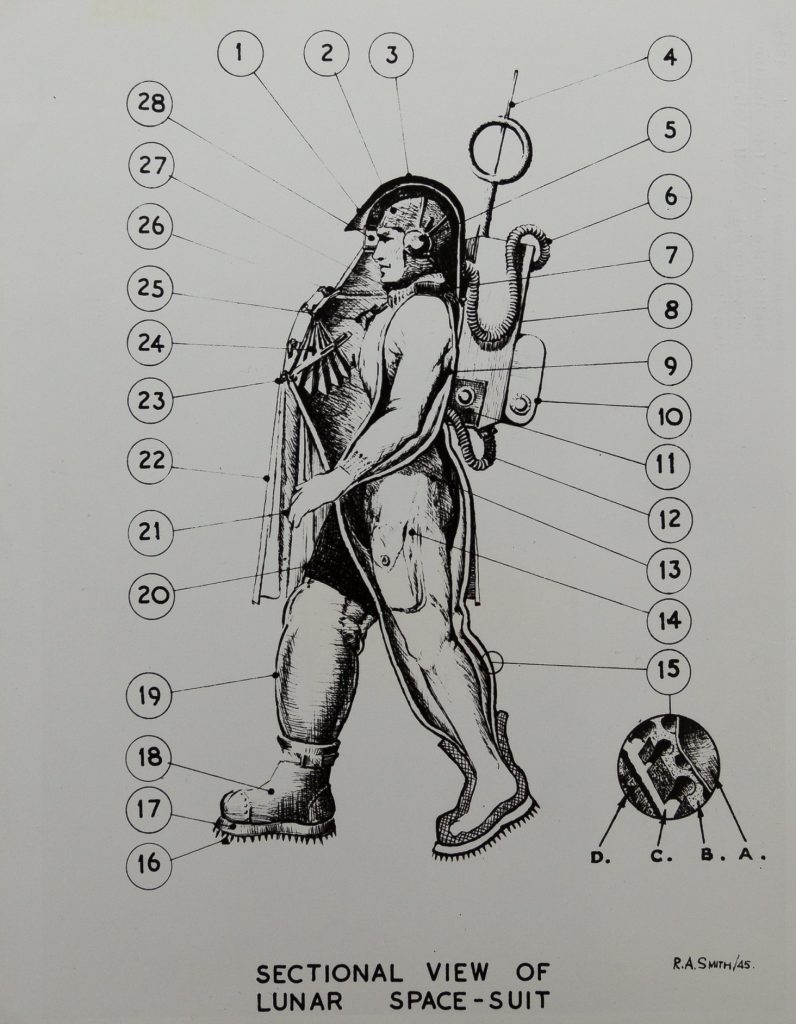

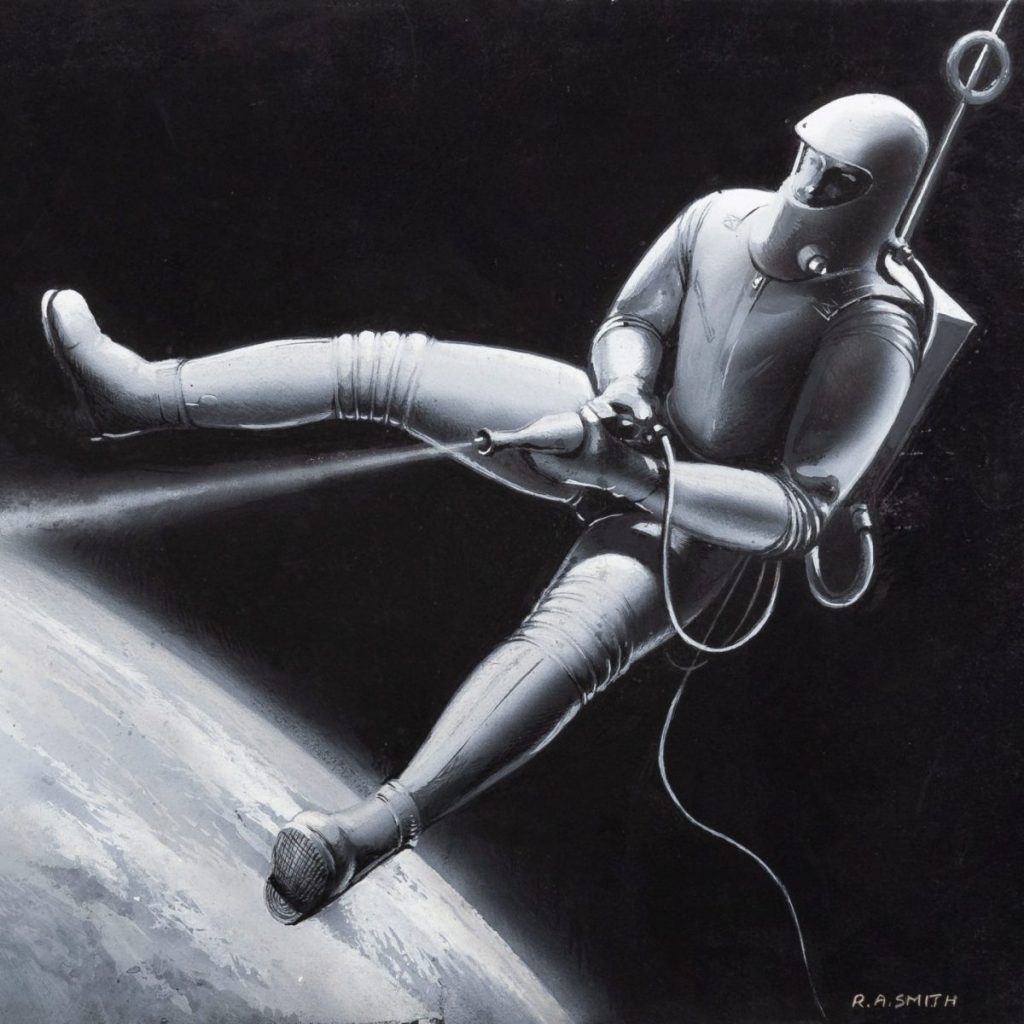

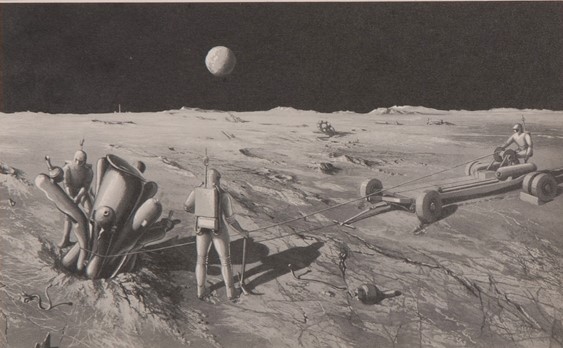

Produced in the 1940s and 50s, much of it looks like it should grace the covers of a period science fiction magazine. Astronauts wear quaint space suits and helmets that make them resemble deep-sea divers; a rocket poised to leave Earth with a needle-sharp nose and tapered fins looks like a cartoon; a lunar lander has the appearance of a tin can with a bullet nose supported on legs of scaffolding.

However these are not just the imaginative sketches of a comic book illustrator. They are based on meticulously crafted designs, the result of many hours of complex calculations and detailed specification by engineers of the British Interplanetary Society (BIS).

Harry Ross and Ralph Smith worked as an inseparable team to devise practical solutions to the problems of spaceflight more than a decade before Russia’s satellite, Sputnik, inaugurated the Space Age in October 1957. In addition to his technical credentials Smith was also a talented artist, able to bring vividly to life their concepts for how the human race would, firstly, investigate space with robotic craft, and later send astronauts to explore the Moon and Mars.

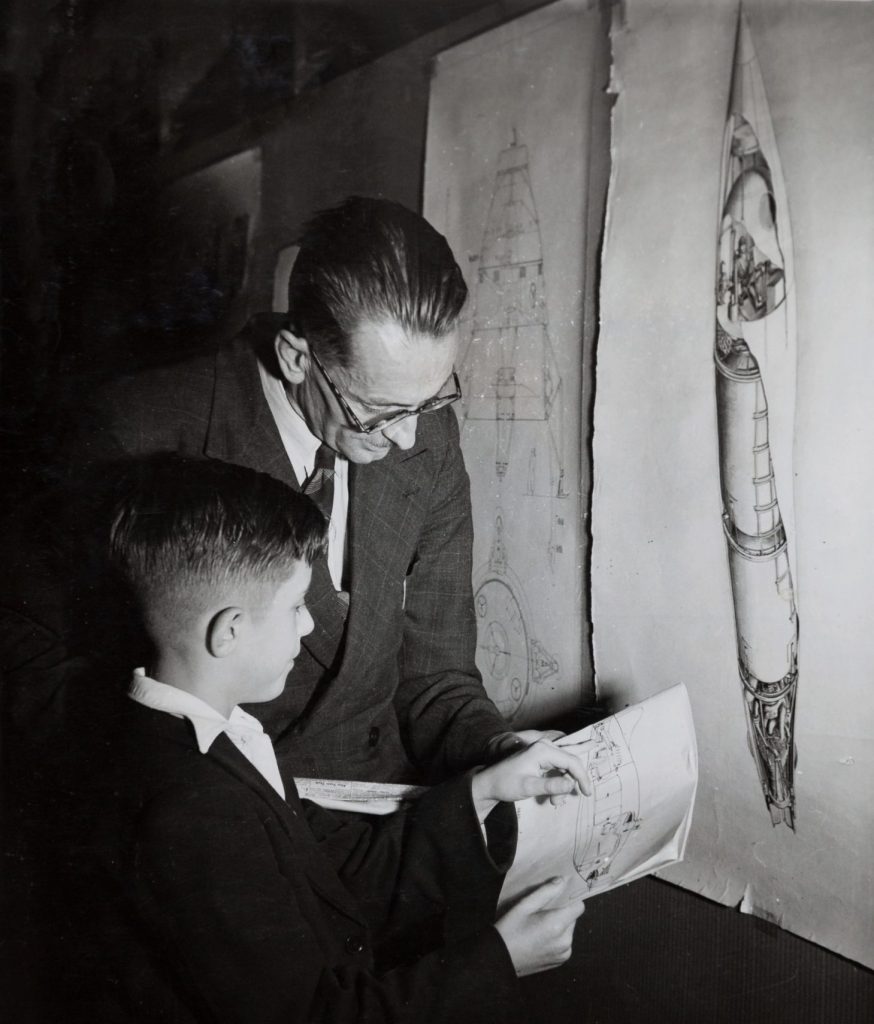

Then based in Buckinghamshire, the pair achieved early recognition by appearing in a Pathé News item in 1947. The black-and-white newsreel film clip shows them both dressed smartly in waistcoat, collar and tie, at the drawing board busy on their plans for spaceships, a lunar base and space suits. The commentator points out, perhaps a little sceptically, the rocket that will ‘take them from High Wycombe to the Moon’ and ‘the landing base they will build – if they get there’.

Smith’s rocket drawing in the newsreel was the Megaroc, their design for a heavily modified German V2 rocket to carry a British pilot on a test flight into space to an altitude of 300km. The V2 had already proven its credentials during the Second World War by making history as the first man-made object to enter space. Quite incidental to its main purpose, the rocket left the Earth’s atmosphere at the top of its flight arc on 1,400 launches to bomb London – not least Vauxhall, which sustained some of the highest casualties from a single V2 attack that struck Lambeth Baths in Morton Place.

Smith and Ross proposed the Megaroc project to the British Ministry of Supply in December 1946, outlining how a capsule on top of the rocket would return the pilot inside his cabin to Earth by parachute, with a collapsible skirt cushioning the final impact with the ground. Careful programming of the engine thrust meant the solo astronaut would experience no more that 3.3 times the force of gravity, compared with the 8G endured by Yuri Gagarin on the first manned space flight, just 14 years later.

The idea was championed by the journalist Chapman Pincher, who knew about rocketry from wartime service in the Royal Armoured Corps, but was rejected by the government. NASA would use essentially the same idea in the Mercury-Redstone flights that put their first astronaut, Alan Shepard, into space.

Britain, unlike France, USA and Russia, showed no interest in developing the German V2 rockets they had captured during the war, let alone producing a manned version. In true Civil Service style, Smith’s provocative letter was quietly filed away. The first British citizen would not fly into space until Helen Sharman was launched on a Soviet rocket to the Mir space station 43 years later.

Anticipating another space development which has since come to fruition, on 23 November 1948, Ross and Smith presented a ground-breaking paper to the British Interplanetary Society on building and maintaining a space station. The orbital platform would be crewed by 24 scientists, who would conduct experiments in zero gravity and perform astronomical observations. The station, they suggested, could be resupplied with oxygen and other life-support essentials by supply ships launched every three months.

It seemed like another dead-in-the-water proposal, except that the History Office of the US space agency NASA acknowledged its importance on the 65th anniversary of that BIS meeting in 2013. Its own International Space Station, precisely as envisaged by the BIS pair, is re-supplied by automatic craft every few months – albeit it has only ever held a maximum crew of 13.

Many of the plans and practical designs which Ross and Smith worked out were later adopted by the British science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, also a Fellow of the BIS, for his highly successful novels – and not always acknowledged.

Ralph Andrew Smith said he designed his first spaceship at the age of twelve, in 1917. That drawing no longer exists, but his artistic legacy is an extensive collection of line drawings and paintings covering a wide range of automatic and human space activities which have almost all come to fruition. He invariably signed his work R. A. Smith.

Smith was Chairman of British Interplanetary Society from 1956 to 1957 and lived to see the first satellite orbit the Earth, a vindication of the prescient designs he worked on with Harry Ross and captured so skilfully in his artwork. He suffered a stroke in 1958 and died suddenly the following year.

Smith’s art was published in The Exploration of the Moon by R.A. Smith with text by Arthur C. Clarke and Frederick Muller (Harper & Brothers, 1954). It displays 45 of his works, including those whose originals hang in Vauxhall, mostly reproduced in black-and-white with a few in colour.

In 1979, the BIS published a more comprehensive paperback collection, High Road to the Moon: From Imagination to Reality by R.A. Smith with commentary by Bob Parkinson. BIS is to publish a new edition, replacing many of the black-and-white reproductions with colour versions of the space art of Ralph Smith.

The Society

The British Interplanetary Society was founded in 1933 and remains Britain’s leading organisation for promoting space flight, attracting a world-wide membership. It produces the monthly news-stand magazine SpaceFlight.