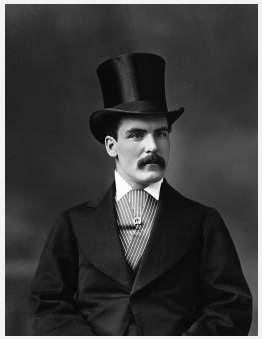

Thomas Neill Cream

Dr Thomas Neill Cream was a Glasgow-born poisoner, who claimed his first proven victims in America and the rest in England, with possibly others in Canada and Scotland. He was undone when he attempted to frame other people for his crimes and he was executed in England in 1892. He was cross-eyed and had a bizarre, self-destructive personality.

Cream was born in Glasgow on 27 May 1850 and his family emigrated to Canada when he was four. He graduated in medicine from McGill University aged 25. Soon after this he underwent a shotgun wedding with Flora Brooks, but abandoned her the day after the wedding. He had earlier nearly killed her while aborting her baby.

Cream returned to the UK to study surgery at St Thomas’ Hospital, London. However, he failed the entrance requirements so took a job as an obstetrics clerk. While in London he sent Brooks, still legally his wife, some pills and she died in suspicious circumstances.

Cream was accepted by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons in Edinburgh and licensed in midwifery. In late 1878 he returned to Canada and set up practice in London, Ontario, where he was implicated in the murder of a new patient, Kate Gardener. Gardener was unmarried and pregnant at the time and had gone to Cream for an abortion, she was later found dead in a nearby woodshed which smelled strongly of chloroform. At her inquest, Cream admitted having been consulted by Gardener but said he had refused to help with the abortion and suggested she must have taken her own life. He alleged that she was pregnant by a prominent local businessman. As there was no bottle found near the corpse, and the face was badly scratched as though she had been trying to remove a mask or pad, the inquest ruled that she had been murdered.

Cream was not tried due to insufficient evidence. However, his reputation was ruined, and he moved shortly afterwards to Chicago to practice as a physician. He was based near a red light district and offered terminations to prostitutes. He was quickly suspected by the Chicago police of being an illegal abortionist. In 1880 he was charged with the death of an abortion patient, Mary Ann Faulkner, but escaped prosecution through lack of evidence. Cream also marketed his own anti-pregnancy pills and one patient, Ellen Stack, died of strychnine poisoning. Again, Cream was not brought to justice through lack of evidence. In 1881 he almost got away with poisoning Daniel Stott, a patient whose wife he had seduced. But Cream felt compelled to contact the District Attorney, maintaining that the chemist who had made up the pills he had prescribed for Stott had added strychnine to them. When the District Attorney ordered the exhumation of Stott’s body, it was found to contain strychnine but the finger of suspicion pointed at Cream not the blameless chemist and he was charged with murder. At his trial he received a life sentence but as a result of bribery he ended up serving only ten-year prison term in Illinois’ Joliet State Penitentiary.

On his release in July 1891 and after a brief period in Canada with his relatives he moved back to the UK. From September 1891 he lodged at 103 Lambeth Palace Road, where he resumed his deadly career. Despite a three-month trip back to Canada, in the six months to 12 April 1892 he murdered four prostitutes: Ellen Dosworth, Matilda Clover, Emma Shrivell and Alice Marsh. Going under the name of Dr Neill of St Thomas’ Hospital, and wearing his usual attire of a top hat and a silk lined cloak, Cream would befriend his victims and offer medication laced with strychnine, supposedly to clear up rashes or spots.

However, Cream again incriminated himself. He blamed the murders on Walter Harper, a medical student and fellow lodger, and wrote to Harper’s father demanding £150 to destroy some supposed evidence. He also pestered the police with his theories as to the identity of the murderer and even wrote under different pseudonyms to a coroner implicating Harper and Frederick Smith M.P. Smith also received a letter asking for £3,000 to destroy some supposed evidence. Other blackmail letters were sent to Dr William Broadbent of Portland Square and Lord Russell. Cream, using his false name Neill, got chatting with a former New York Detective John Haynes at a photographic studio. Haynes became worried by the amount of detail that Cream was relaying about the murders, including the names of two victims who had not been associated with the poisonings. The next day Haynes spoke to his Metropolitan Police friend Inspector Patrick McIntyre about Neill/Cream. Cream was followed and the police sent enquiries to Canada and Chicago. One of the ‘new’ victims mentioned by Neill/Cream was a woman called Louise Harvey. However, Harvey was not dead – she had sensed that there was something wrong with Cream and had pretended to swallow the pills he had given her.

Cream was initially charged with attempted extortion and a mass of evidence, including seven bottles of strychnine, was collected from his lodgings. He was subsequently charged with the murder of Matilda Harper. The jury took only 12 minutes to establish his guilt and he was hanged on 15 November 1892. There is an unsubstantiated claim that at the moment the trap door opened under him Cream made a false confession to being Jack the Ripper (he was in a Canadian prison at the time of those murders).