Vauxhall Gardens was an open-air resort and the English climate being what it is, there had to be an ‘if wet, indoors’ option. This was The Rotunda, which opened in 1748, offering concerts and exhibitions as well as shelter. Pulled down when the gardens closed in 1859, The Rotunda rose again in 2019 as a Virtual Reality (VR) construct, the first fruit of a proposal to recreate Vauxhall Gardens in VR. The proposal came from Lars Tharp, a mainstay of BBC’s Antiques Roadshow, and David E. Coke, co-author with Alan Borg of Vauxhall Gardens: A History and Consultant Editor of vauxhallhistory.org.

David and Lars approached the composer and digital music specialist Professor Andrew Hugill of Leicester University with a proposal for developing a VR model of Vauxhall Gardens. Professor Hugill could see a way to encapsulate the notion of ‘creative computing’ by building such a model, beginning with the Rotunda. An exhibition, Virtual Vauxhall Gardens, was held at Leicester University’s Attenborough Arts Centre, which is named after the film actor/director Richard, Lord Attenborough. Vauxhall Gardens fans may still – by appointment – don a headset and so be able to interact with, look and move around inside the recreated Rotunda. Contact: Leicester Innovation Hub at leicinnovation@le.ac.uk or phone 44 (0)116 373 6471. Andrew Hugill now takes up the story.

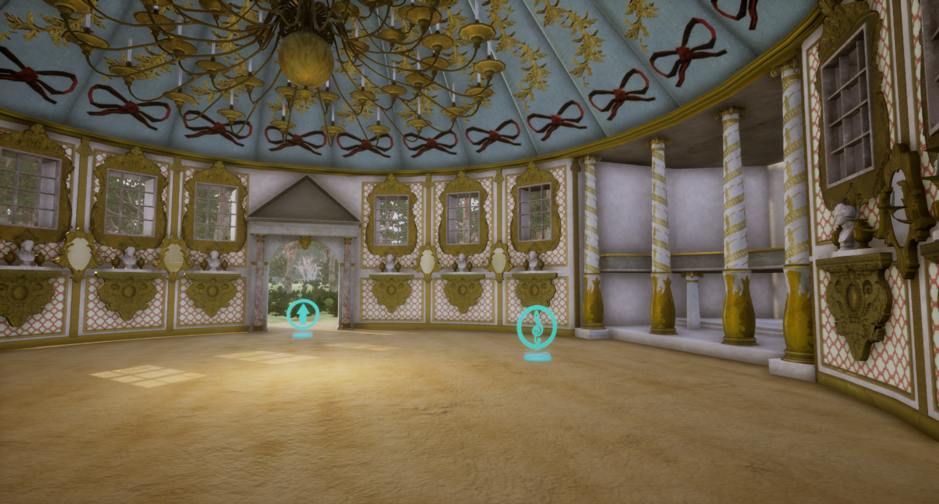

Friday 16 July 2019 saw the launch of Virtual Vauxhall Gardens in the Attenborough Arts Centre, Leicester. Visitors were invited to experience an interactive virtual visit to the Rotunda in 1752 by wearing VR headsets and using vision to move through the story. One of the VR headsets had the addition of an olfactory device: the smell of beeswax, which was activated when the viewer lit the fuse of the spectacular 72-candle chandelier. The exhibition also contained posters describing the project in detail and a slideshow about the history of Vauxhall Gardens.

The project is a collaboration between a multidisciplinary team at the University of Leicester, led by Professor Andrew Hugill, and MBD Ltd, a company specialising in Heritage VR. David E. Coke and Lars Tharp were retained as consultants to the project. Funding came from the Leicester Institute of Advanced Studies and the university’s Knowledge Exchange and Enterprise Fund. The exhibition was a great success and there was a steady stream of visitors, including several who had travelled long distances and even a descendant of Jonathan Tyers.

Vauxhall Gardens was re-launched in 1732 as the first and most significant of the true Pleasure Gardens of Georgian London. Commercial pleasure gardens, an English invention, were privately-run sites of entertainment; they were often situated on the outskirts of large towns or cities, and paying visitors were entertained in the summer months with music and company; refreshments were available at a price. Pleasure gardens, as their name implies, were mainly outdoor spaces, though sometimes with an assembly room or concert hall, and they were normally open in the evening, after the working day; anybody who could afford the admission price and who was at least respectably dressed would be admitted.

In re-creating this experience, the team aimed to widen access to and diversify audiences for historical virtual reality environments by engaging the widest range of senses (sound, vision, smell), using creative approaches and targeting non-traditional VR users. The first step was to reconstruct the Rotunda, which was the main hub of entertainment: an indoor space that saw artistic exhibitions and musical performances as well as providing many opportunities for social interaction.

By the 1750s, Jonathan Tyers’s acquisition of Vauxhall’s old Spring Gardens had transformed a dodgy tavern on the south bank of the Thames into a reformed model of civilised entertainment and relaxation, an embodiment of Tyers’s civilising purpose. At an affordable one shilling (equivalent to a labourer’s daily wage), the entrance fee permitted a broad spectrum of London’s population to sample the Gardens’ delights. A spirit of egalitarianism was further encouraged by a particular prohibition: while servants might be allowed, they were not admitted if ‘in livery’ – visible servitude undermined the Gardens’ ethos.

Visitors with deep pockets could order al fresco food and drink, to consume in open-sided ‘supper-boxes’. Each box was backed with a piece of modern art by artists such as William Hogarth and Francis Hayman, depicting pastoral scenes, naval victories and other patriotic subjects that would raise the spirits.

Meanwhile, beyond the central bandstand, tree-lined walks led visitors further off into the gardens’ shadier corners where the occasional sculpture of a famous poet appeared in the shrubbery. For a brief season only, a bed of roses murmured with music (rising from players confined within a hidden subterranean chamber). As daylight faded, the Dark Walk and intersecting avenues were magically illumined with lanterns offering greater (if not total) safety from unwanted suitors of both sexes.

But there was a problem: the London weather. Low skies might deter prospective visitors and looming showers drive out those already there. So, in 1748, Tyers added his Rotunda, a temple-like building, where musicians and audiences might take shelter in the event of ‘weather’. Befitting its purpose as well as its appearance the Rotunda was dubbed ‘The Umbrella’ – the very contraption that was but recently gaining popularity among a few eccentric London pedestrians.

University of Leicester’s Biomechanics and Immersive Technology Laboratory undertook the initial reconstruction of the Rotunda, with advice from the history team and the project consultants, working from various drawings. The resulting structure was passed to MBD, who undertook the work on recreating the decorative features. The model was then textured to create the appearance of the stone, plaster, gold gilt and painted surfaces, before adding the details such as the busts, urns, carvings and even the spectacular 72 candle chandelier. Finally, the model was lit to create the realistic shadows and textured surfaces that really bring the building to life. Everything, right down to the flickering of the candles on the wall was painstakingly recreated to make sure that, when wearing a virtual reality headset, it felt as if you are there.

Meanwhile the History and Literature teams worked with MBD to create a storyline and provide appropriate imagery, music and voiceover content. The VR experience takes the viewer on a surreal boat trip to the Gardens (visitors would have arrived by boat) and builds the structure of the Rotunda around them on arrival and the reverse on departure.

While multisensory installations are not in themselves new, we are aiming to achieve a new level of user control and experience with this project. The olfactory component that was added to one of the displays was a first attempt to combine sensory inputs within a single experience. Smell is the oldest of the senses and largely bypasses the neocortex. Miasma theory of smell was used historically as an account for the spread of disease through smell (which accounts for our use of deodorants today). Historically a figure of 10,000 different smells was the perception limit, but now argued to be 1 trillion, with new odorous molecules being invented every day. In humans, olfaction works by triggering 10 million olfactory receptors in a unique pattern for each odour – population code. The VR model used only a single smell, and it was surprising to observe that many people assumed there were more – even up to six! Perhaps the brain, on being told that smell will be included, becomes super-responsive to any olfactory trigger. This is something we will be investigating in the future.

We will also be conducting some psychology experiments in the coming months, to test the extent to which such a multisensory experience enhances user experience and understanding of the historical aspects. We are also interested in exploring how people with sensory processing issues might be able to experience and enjoy VR.