Sean Creighton, biographer of John Archer, relates how over a century ago this black progressive and Labour activist battled for greater fairness for all in Battersea and beyond.

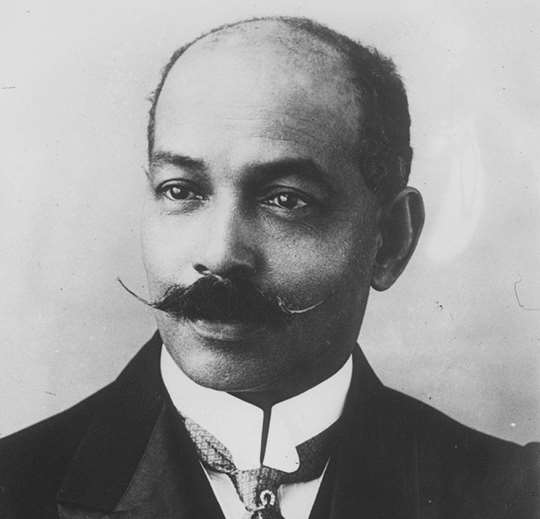

John Archer (1863-1932), the Mayor of Battersea in 1913/14, is an important figure in the story of the black contribution in Britain. As a black man he represented Battersea’s white working class in the early part of the 20th century and was particularly associated with the Nine Elms district. A Roman Catholic, he attended the Church of Our Lady of Carmel, next to Battersea Park Road Railway Station.

Little is known about his early life, except that he was born in July 1863 in Liverpool to Mary Theresa Burns, a Catholic Irishwoman, and John Archer, a ship’s steward from Barbados, that he may have worked as a seaman, and that in the early 1890s he and his wife Margaret, a black Canadian, settled in Battersea. By 1898 the Archers were living just off Battersea Park at 55 Brynmaer Road. While they were living there, in the years up to her death in January 1914, John and Margaret looked after Jane Roberts, the African-American widow of Joseph Jenkins Roberts, the first black President of the independent state of Liberia. Margaret appears to have died in the late 1910s or early 1920s as Archer married Bertha E. White in 1923; there were no children of either union.

Archer knew which side of the political argument he was on: he was against injustice whether on class or racial grounds. He became involved with a network of black and anti-colonial activists, leading in 1900 to his attendance at a Pan-African Conference in Westminster Town Hall. Here he mingled with leading campaigners from the ‘Black Atlantic’, people of African descent living in Europe, the Caribbean, and the Americas, including the Croydon-based Anglo-Sierra Leonean composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. Archer and Coleridge-Taylor became members of a committee to campaign for black rights.

In the 1901 Census, Archer’s occupation was recorded as singer. By 1906 he had become a professional photographer with a shop in Battersea Park Road. That same year he was elected as a Councillor for the labour, liberal and radical Progressive Alliance. In the Tory rout of the Alliance in 1909 most Progressives lost their seats, Archer included, but in 1912 he was re-elected. In November 1913 he was elected Mayor of Battersea and during his year in office chaired council meetings, as well as furthering local charities and civic groups, including the Nine Elms Swimming Club. His election attracted hundreds of congratulatory messages from the Black Atlantic.

Archer’s last months in office were dominated by the outbreak of the First World War. He set up a relief fund for the families of men who had enlisted in the armed forces. Both Battersea Council and local activists thanked him with special presentations at the end of his year as Mayor.

He served as a member of the Wandsworth Board of Guardians which administered help to the poor, disabled and elderly. He highlighted abuse of power by officials, and championed people who, by the standards of the time, were regarded as ‘undeserving’. He also fought cuts in financial support to the needy, especially when so many ex-servicemen could not get work after the war ended. As political arguments about the treatment of the unemployed heated up from 1922, Archer’s activism earned himself the title of the ‘K.C.’ (King’s Counsel) for the Unemployed’. These arguments culminated in October 1923, when the Chairman of the Board of Guardians suspended all the Labour members. Archer had to be physically carried out.

In December 1918 Archer became President of the newly-formed African Progress Union and in 1919 led an APW deputation to Liverpool to discuss the attacks on black seamen there. Archer attended the Pan-African Congress in 1919 and 1921, at the latter introducing the Labour/Communist Party member Shapurji Saklatvala. Archer supported Saklatvala to be Battersea’s Labour’s Parliamentary candidate. ‘Sak’ was elected to Parliament in 1922, lost his seat in 1923 and was re-elected 1924. The Battersea party was expelled from the national Labour Party for defying a ban on dual Labour/Communist membership. Sak was arrested during the General Strike in May 1926. The police found a letter in which he advised the Communist Party to destroy the Labour Party. The letter was given to the press. Archer was among those who considered Sak to have betrayed their support.

After the General Strike of 1926, Archer became a key figure in setting up new local Labour Party organisations affiliated to the national party. Although no longer a member of Battersea Council, he represented the body at several national and international health conferences between 1926 and 1928, and the following year, as election agent, he helped William Sanders replace Sak as MP. In his final years his premises in Battersea Park Road doubled as Labour Party offices. Again elected to Battersea Council in November 1931 for the Nine Elms Ward, the indefatigable K.C. for the Unemployed became Labour Deputy Leader.

Archer fell ill, dying on Thursday 14 July 1932 aged 68. The funeral was held at Our Lady of Carmel and children from local church schools sang the Dies Irae. He was buried at Morden cemetery (his grave has been recently restored) and was commemorated not long after his death by Archer House, a block of flats in Battersea Village. There is also a John Archer Way. In 2010 the Nubian Jak Community Trust, who honour stalwarts of black history, erected a plaque on the building in Battersea Park Road where Archer’s shop once stood, and in 2013, the centenary of Archer’s mayoralty, the Royal Mail included him in a series of first class stamps and English Heritage put a blue plaque on his home at 55 Brynmaer Road.

Sean Creighton’s John Archer: Battersea’s Black Progressive and Labour Activist 1863-1932 (2014) is available from History & Social Action Publications.

Sean Creighton’s John Archer: Battersea’s Black Progressive and Labour Activist 1863-1932 (2014) is available from History & Social Action Publications.