This obituary for Florence Nightingale appeared in The Times on August 15, 1910.

We deeply regret to state that Miss Florence Nightingale, O.M., the organizer of the Crimean War Nursing Service, died at her residence, 10, South-street, Park-lane, on Saturday afternoon. She had been unwell about a week ago, but had recovered her usual cheerfulness on Friday. On Saturday morning, however, she became seriously ill and she gradually sank until death occurred about 2 o’clock. The cause of death was heart failure. Two members of her family were present at the time.

Miss Nightingale, who had for some time been an invalid and had been under the constant care of Sir Thomas Barlow, was in her 91st year. She celebrated her 90th birthday on May 12 last, and one of the first acts of the present King since coming to the throne-King Edward had died on May 6-was to send her a telegram of congratulation. The message was worded as follow:-

“On the occasion of your 90th birthday I offer you my heartfelt congratulation, and trust that you are in good health.-GEORGE R. & I.”

The funeral will take place in the course of the next few days, and will be of the quietest possible character in accordance with the strongly expressed wish of Miss Nightingale.

MEMOIR

In Miss Florence Nightingale there has passed away one of the heroines of British history. The news of her death will be received to-day with feelings of profound regret throughout not merely the land of her birth, but in all lands where her name has been spoken among men.

Florence Nightingale was born May 12, 1820, at Florence, from which city she took her name. She was the younger of the two daughters and co-heiresses of Mr. William Shore Nightingale, of Embley Park, Hampshire, and Lea Hall, Derbyshire, a descendant of the old Derbyshire family of Shore, and himself the possessor of large estates and considerable wealth. Her mother was a daughter of William Smith, the friend of Wilberforce and his supporter in the House of Commons in the abolitionist and other movements. From Lea Hall the family removed, about 1926, to Lea Hurst, a house about a mile distant, and the one with which the name of Florence Nightingale has been more especially associated. Florence, who even in her young days was a child of extremely strong sympathies, quick apprehension, and excellent judgment, was carefully trained, acquiring, among other accomplishments, under the direction of her father, a knowledge of the classics, mathematics, and also of modern languages. But while applying herself to the culture of her mind she was, at the same time, the consoler and benefactress of all the villagers to whom her help or her kindly words might be of service, displaying even thus early in life that bent of her mind and disposition which afterwards spread her fame throughout the world.

Seeking for wider experience than her position as a square’s daughter in a small Derbyshire village could give her, she visited all the hospitals in London, Dublin, and Edinburgh, many country hospitals, and some of the naval and military hospitals in England; all the hospitals in Paris, studying with the Sœurs de Charité; the Institute of Protestant Deaconesses at Kaiserswerth, on the Rhine, where she was twice in training as a nurse; the hospitals at Berlin, and many others in Germany; while she also visited Lyons, Rome, Alexandria, Constantinople, and Brussels. On her return to Derbyshire, where she hoped to have the rest of which she stood in need after her travels, she was appealed to, in 1850, on behalf of the Home for Sick Governesses, 90, Harley-street, London, which was languishing from lack, not only of proper support, but also of proper management. She responded to the appeal by herself taking over the entire control of the institution, and devoting alike time, energy, and fortune to re-establishing it (with the help of Lady Canning, the original founder) on a sound basis. She also took an active interest in the ragged schools and other similar institutions in London. Altogether something like ten years had been spent by her in preparing, unconsciously, for the great events of her life, and these came with the Russian war.

THE CRIMEAN WAR

On September 20, 1854, the battle of Alma was fought, and it is not too much to say that the accounts published in the columns of The Times from our Correspondent, the late Dr. (afterwards Sir William Howard) Russell as to the condition of the sick and wounded sent a feeling of horror throughout the length and breadth of the land. There is no necessity to dwell here in detail on the harrowing stories he related. Suffice it to say that he showed how the commonest accessories of a hospital were wanting; how the sick appeared to be tended by the sick, and the dying by the dying; how, indeed, the manner in which the sick and wounded were being treated was “worthy only of the savages of Dahomey”; and how, while our own medical system was “shamefully bad,” that of the French was exceedingly good, and was, too, rendered still more efficient because of the sisters of charity who had followed the French troops in incredible numbers.

On October 12, 1854, a leading article appeared in The Times in which it was pointed out that while “we are sitting by our firesides devouring the morning paper in luxurious solitude…these poor fellows are going through innumerable hardships”; and the article went on to suggest that the British public should subscribe to send them “a few creature comforts.” On the following day we published an extremely sympathetic letter from Sir Robert Peel, starting a fund with a cheque for £200, and so generally and so liberally was his example followed that £781 was received by us within two days, £7,000 within seven days, and £11,614 by the end of the month, when the fund was closed. But, in the meantime, the terrible cry from the East had met with a response which was of even more effectual service to the suffering soldiers than the thousands of pounds thus promptly and generously contributed. On October 15, Miss Nightingale wrote to Mr. Sidney (afterwards Lord) Herbert, Secretary at War, offering to go to Scutari, and, as it happened, her own letter was crossed by one to herself from Mr. Sidney Herbert. Medical stores, he said, had been sent out by the ton weight, but the deficiency of female nurses was undoubted. Lady Maria Forrester had proposed to go with or to send out trained nurses, “but there is,” Mr. Herbert went on to say, “only one person in England that I know of who would be capable of organizing and superintending such a scheme.…A number of sentimental and enthusiastic ladies turned loose in the hospital at Scutari would probably, after a few days, be mises à la porte by those whose business they would interrupt and whose authority they would dispute. My question simply is, Would you listen to the request to go out and supervise the whole thing?” Miss Nightingale, as we have seen, had already answered this question, and preparations could thus be set on foot without a moment’s delay. But, as showing how little she was known to fame at that time, we may mention as a curious fact that in The Times of October 19, 1854, there appeared the announcement,-“We are authorized to state that Mrs. (sic) Nightingale” had undertaken to organize a staff of female nurses, who would proceed with her to Scutari at the cost of the Government. Not, indeed, until several days had elapsed does it seem to have been realized that “Mrs.” Nightingale was really “Miss” Nightingale, and even then the Examiner found it necessary to publish an article, headed “Who is Miss Nightingale?” setting forth who she really was, and bearing eloquent testimony to her accomplishments, her experience, and the nobility of her character.

Within a week Miss Nightingale had selected from hundreds of offers, received from all parts of the country, a staff of 38 nurses, including 14 Anglican sisters, ten Roman Catholic sisters of mercy, and three nurses selected by Lady Maria Forrester. It may be interesting to recall that among the ladies forming the gallant little band was Miss Erskine, eldest daughter of the Dowager Lady Erskine, of Pwll-y-crochan, North Wales. Miss Nightingale and her nurses left London on October 21, passing through Boulogne on October 23 on their way to Marseilles; and a letter which appeared in The Times some days afterwards, written by a correspondent who had been staying at Boulogne, related how the arrival of the party there caused so much enthusiasm that the sturdy fisherwomen seized their bags and carried them to the hotel, refusing to accept the slightest gratuity; how the landlord of the hotel gave them dinner, and told them to order what they liked, adding that they would not be allowed to pay for anything; and how waiters and chambermaids were equally firm in refusing any acknowledgment for the attentions they pressed upon them.

ARRIVAL AT THE FRONT

From Marseilles the party proceeded to Constantinople, where they arrived on November 4, the eve of the battle of Inkerman. They found there were two hospitals at Scutari, of which one, the Barrack Hospital, already contained 1,500 sick and wounded, and the other, the General Hospital, 800, making a total of 2,300 but on the 5th of November there arrived 500 more who had been wounded in the course of that day’s fighting, so that there were close on 3,000, sufferers claiming the immediate attention of Miss Nightingale and her companions. In the best of circumstances the task which the nurses thus found before them would have been enormous; but the circumstances themselves were as bad as the imagination can conceive, if, indeed, imagination, unaided by fact, could call up so appalling a picture. Neglect, mismanagement, and disease had “united to render the scene one of unparalleled hideousness.” The wounded, lying on beds placed on the pavement itself, were bereft of all comforts; there was a scarcity alike of food and medical aid; fever and cholera were rampant, and even those who were only comparatively slightly wounded, and should have recovered with proper treatment, were dying from sheer exhaustion brought about by lack of the nourishment they required.

Miss Nightingale, as “Lady-in-Chief,” at once set to work to restore something like order out of the chaos that prevailed. Within ten days of her arrival she had had an impromptu kitchen fitted up, capable of supplying 800 men every day with well-cooked food, and a house near to the Barrack Hospital was converted into a laundry, which was also sorely needed. In all this work she was most cordially supported by Mr. MacDonald, the almoner of The Times Fund, the resources of which were, of course, freely placed at her disposal. But in other directions Miss Nightingale had serious difficulties to encounter. The official routine which had sat as a curse over the whole condition of things continued as active, or, rather, as inefficient, as ever. Miss Nightingale was at first scarcely tolerated by those who should have co-operated with her. She had, at times, the greatest possible difficulty in obtaining sufficient Government stores for the sick and wounded; for though, as Mr. Sidney Herbert had written, medical stores had been sent out by the ton weight, they were mostly rotting at Varna instead of having been forwarded to Scutari. On one occasion, when she was especially need of some that had arrived, but were not to be given out until they had been officially “inspected,” she took upon herself to have the doors opened by force and to remove what her patients needed.

But her zeal, her devotion, and her perseverance would yield to no rebuff and to no difficulty. She went steadily and unwearyingly about her work with a judgement, a self-sacrifice, a courage, a tender sympathy, and withal a quiet and unostentatious demeanour that won the hearts of all who were not prevented by official prejudices from appreciating the nobility of her work and character. One poor fellow wrote home:-“She would speak to one and nod and smile to a many more; but she could not do it to all, you know. We lay there by hundreds; but we could kiss her shadow as it fell, and lay our heads on the pillow again, content.” Mr. MacDonald, too, wrote in February, 1855:-

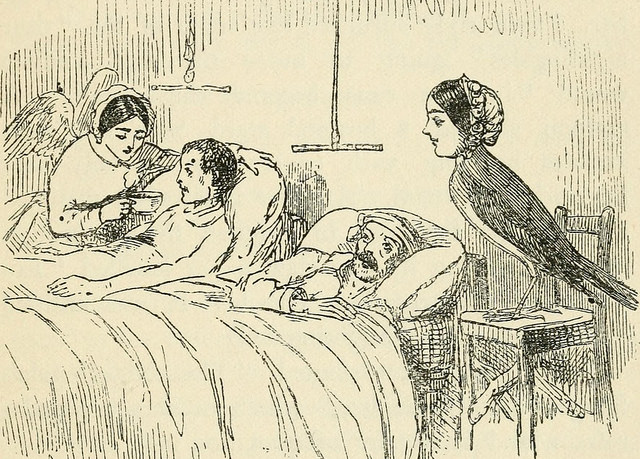

Wherever there is disease in its most dangerous form and the hand of the despoiler distressingly nigh, there is that incomparable woman sure to be seen. Her benignant presence is an influence for good comfort, even amid the struggles of expiring nature. She is a “ministering angel” without any exaggeration in these hospitals, and as her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every poor fellow’s face softens with gratitude at the sight of her. When all the medical officers have retired for the night and silence and darkness have settled down upon those miles of prostrate sick, she may be observed alone, with a little lamp in her hand, making her solitary rounds. The popular instinct was not mistaken which, when she set out from England on her mission of mercy, hailed her as a heroine. I trust she may not earn her title to a still higher though sadder appellation. No one who has observed her fragile figure and delicate health can avoid misgivings lest these should fail. With the heart of a true woman, and the manner of a lady, accomplished and refined beyond most of her sex, she combines a surprising calmness of judgment and promptitude and decision of character.

It was also written of her:-

She has frequently been known to stand 20 hours on the arrival of fresh detachments of sick, apportioning quarters, distributing stores, directing the labours of her corps, assisting at the painful operations where her presence might soothe or support, and spending hours over men dying of cholera or fever. Indeed, the more awful to every sense any particular case might be the more certainly might be seen her slight form bending over him, administering to his ease by every means in her power, and seldom quitting his side till death released him.

CRITICISM AT HOME

Meanwhile the reports which Miss Nightingale made both to Lord Raglan, the Commander-in-Chief, and to the War Minister at home were of invaluable service in enabling them to put their finger on the weak spots of the administration. On the other hand, it is painful to recall the fact that while, in all these various ways, Miss Nightingale was doing such admirable work in the East, sectarian prejudices at home had led to unscrupulous attacks being made alike on her religious views and on her motives in going out. “It is melancholy to think,” as Mrs. Herbert wrote to a lady correspondent, “that in Christian England no one can undertake anything without these most uncharitable and sectarian attacks.…Miss Nightingale is a member of the Established Church of England, and what is called rather Low Church; but ever since she went to Scutari her religious opinions and character have been assailed on all points. It is a cruel return to make towards one to whom all England owes so much.” Happily a check was put to this campaign of slander and uncharitableness by a letter written by Queen Victoria from Windsor Castle, dated December 6, 1854, to Mr. Sidney Herbert, asking that accounts received from Miss Nightingale as to the condition of the wounded should be forwarded to her, and saying:-

“I wish Miss Nightingale and the ladies would tell these poor noble wounded and sick men that no one takes a warmer interest, or feels more for their sufferings, or admires their courage and heroism more, than their Queen. Day and night she thinks of her beloved troops. So does the Prince. Beg Mrs. Herbert to communicate these my words to those ladies, as I know that our sympathy is much valued by these noble fellows.”

The eminently tactful indication conveyed in this letter of her Majesty’s complete confidence in Florence Nightingale did much not only towards silencing the ungenerous critics at home, but also towards strengthening the position of the Lady-in-Chief in meeting the difficulties due to excessive officialism in the East.

From The Life of Florence Nightingale, by Sarah A. Southall Tooley. London : S. H. Bousfield & Co., 1905

GROWTH OF THE WORK

In January, 1855, Miss Nightingale’s totally inadequate staff was increased by the arrival of Miss Stanley with 50 more nurses; and how greatly they were needed is shown by the fact that there were then 5,000 sick and wounded in the various hospitals on the Bosporus and the Dardanelles, 1,000 more being on their way down. By February there was a great increase of fever, which in the course of three or four weeks swept away seven surgeons, while eight more were ill, twenty-one wards in the Barrack Hospital being in charge of a single medical attendant. Two of the nurses also died from fever. Miss Nightingale told subseqently how for the first seven months of her stay in the Crimea the mortality was at the rate of 60 per cent. per annum from disease alone, a rate in excess, she added, of that which prevailed among the population of London during the Great Plague. By May, however, the position of affairs had so far improved at Scutari, thanks mainly to the untiring energies and devotion of Miss Nightingale, that she was able to proceed to Balaclava to inspect the hospitals there. Her work at Balaclava was interrupted by an attack of Crimea fever, and she was afterwards urged to return home; but she would go no further than Scutari, remaining there until her health had been re-established. Thereupon she again left for the Crimea, where she established a staff of nurses at some new camp hospitals put up on the heights above Balaclava, and took over the superintendence of the nursing department, herself living in a hut not far away. She also interested herself in organizing reading and recreation huts for the army of occupation, securing books and periodicals from sympathizers at home. Among the donors were Queen Victoria and the Duchess of Kent. Another institution she set up was a café at Inkerman, as a counter-attraction to the ordinary canteens. Then she started classes, supported the lectures and schoolrooms which had been established by officers or chaplains, and encouraged the men to write home to their families. Already at Scutari she had opened a money-order office of her own, through which the soldiers could send home their pay. She thus set an example which the Government followed by establishing official money-order offices at Scutari, Balaclava, Constantinople, and elsewhere. Some £70,000 passed through these offices in the first six months of 1856.

THE END OF THE WAR

Florence Nightingale remained in the Crimea until the final evacuation in July, 1856, her last act before leaving being the erection of a memorial to the fallen soldiers on a mountain peak above Balaclava. The memorial consisted of a marble cross 20ft. high, bearing the inscription, in English and Russian-

LORD HAVE MERCY UPON US.

GOSPODI POMILORI NASS.

Calling at Scutari on her way home, Miss Nightingale left that place in a French vessel for Marseilles, declining the offer made by the British Government of a passage in a man-of-war, and reached Lea Hurst on August 8, 1856, having succeeded in avoiding any demonstration on the way.

Before returning to England Florence Nightingale had received from Queen Victoria an autograph letter with a beautiful jewel, designed by Prince Albert; the Sultan had sent her a diamond bracelet; and a fund for a national commemoration of her services had been started, the income from the proceeds, £45,400, being eventually devoted partly to the setting up at St. Thomas’s Hospital of a training school for hospital and infirmary nurses and partly to the maintenance and instruction at King’s College Hospital of midwifery nurses. For herself she would have neither public testimonial nor public welcome. She was honoured by an invitation to visit the Queen and Prince Consort at Balmoral in September, and addresses and gifts from working men and others were sent or presented privately to her. But though her fame was on every one’s lips, and her name has ever since been a household word among the peoples of the world, her life from the time of her return home was little better than that of a recluse and confirmed invalid. Her health, never robust, broke down under the strain of her arduous labours, and she spent most of her time on a couch, while in the closing years of her life she was entirely confined to bed.

LATER REFORMS

But, though her physical powers failed her, there was no falling off either in her mental strength or in her intense devotion to the cause of humanity. She was still the “Lady-in-Chief” in the organization of the various phases of nursing which, thanks to the example she had set and the new spirit with which she had imbued the civilized world, now began to establish themselves; she was the general adviser on nursing organization not only of our own but of foreign Governments, and was consulted by British Ministers and generals at the outbreak of each one of our wars, great or small; she expounded important schemes of sanitary and other reforms, though compelled to leave others to carry them out, while at all times her experience and practical advice were at the command of those who needed them.

Almost the entire range of nursing seems to have been embraced by that revolution therein which Florence Nightingale was the chief means of bringing about. Following up the personal services she had already rendered in the East in regard to Army nursing, she prepared, at the request of the War Office, an exhaustive and confidential report on the working of the Army Medical Department in the Crimea as the precursor to complete reorganization at home; she was the means of inspiring more humane and more efficient treatment of the wounded both in the American Civil War and the Franco-German War; and it was the stirring record of her deeds that led to the founding of the Red Cross Society, now established in every civilized land. By the Indian Government also she was almost ceaselessly consulted on questions affecting the health of the Indian Army. On the outbreak of the Indian Mutiny she even offered to go out and organize a nursing staff for the troops in India. The state of her heath did not warrant the acceptance of this offer; but no one can doubt that, if campaigns are fought under more humane conditions to-day as regards the care of wounded soldiers, the result is very largely due to the example and also to the counsels of Florence Nightingale.

But advance no less striking is to be found in other branches of the nursing art as well. In regard to general hospitals, the pronounced success of the nursing school established at St. Thomas’s as the outcome of the Nightingale Fund led to the opening of similar schools elsewhere, so that to-day hospital nursing in general occupies a far higher position in the land than it has ever done before, while this, in turn, advanced the whole range of private nursing in the country. Then, again, the system of district nursing, which is now in operation in almost every large centre of population, has had an enormous influence alike in bringing skilled nurses within the reach of sufferers outside the hospitals, and of still further raising the status of nursing as a profession. “Missionary nurses,” Florence Nightingale once wrote, “are the end and aim of all our work. Hospitals are, after all, but an intermediate stage of civilization. While devoting my life to hospital work, to this conclusion have I always come-viz., that hospitals were not the best place for the sick poor except for severe surgical cases.”

DISTRICT NURSES

District nursing was really set on foot in this country by the late Mr. William Rathbone, who, in compliance with the dying request of his first wife, started a single nurse in Liverpool in 1859 as an experiment. The demand for district nurses soon became so great that more were clearly necessary, and Miss Nightingale was consulted as to what should be done. She replied that all the nurses then in training at St. Thomas’s were wanted for hospital work, and she recommended that a training school for nurses should be started in Liverpool. The suggestion was adopted, and in November, 1861, on being consulted about the plans, she wrote to the chairman of the training school committee:-

God bless you and be with you in the effort, for it is one which meets one of our greatest national wants. Nearly every nation is before England in this matter-viz., in providing for nursing the sick at home; and one of the chief uses of a hospital (though almost entirely neglected up to the present time) is this-to train nurses for nursing the sick at home.

By about 1863 there was a trained nurse at work among the poor in each of the 18 districts into which Liverpool had been divided for the purposes of the scheme. The example of Liverpool was speedily followed by Manchester, where a district nursing association was formed in 1864; the East London Nursing Society was established in 1868, and the Metropolitan and National Association followed in 1874. In the organization of the last-mentioned society Florence Nightingale took the deepest interest, sending to The Times a long letter, in which she expressed her gratification at the idea of the nurses having a central home, set forth in considerable detail the nature and importance of the duties the district nurses were called upon to perform, and appealed strongly-and successfully-for donations towards the cost of a home. After these pioneer societies had been successfully started many others followed; but the greatest development of all was afforded by Queen Victoria’s Jubilee Institute for Nurses, the operations of which have been of the highest importance in spreading the movement throughout the United Kingdom. When, in December, 1896, a meeting was held at Grosvenor House for the purpose of organizing a Commemoration Fund in support of the Institute, a letter from Florence Nightingale was read, in which she expressed the heartiest sympathy with the proposal.

Great and most beneficent changes, again, have followed the substitution in workhouse infirmaries of trained nurses for the pauper women to whose tender mercies the care of the sick in those institutions was formerly left. It was a “Nightingale probationer,” the late Agnes Jones, and 12 of her fellow-nurses from the Nightingale School at St. Thomas’s who were the pioneers of this reform at the Brownlow-hill Infirmary, Liverpool; and it was undoubtedly the spirit and the teaching of Florence Nightingale that inspired them in a task which, difficult enough under the conditions then existing, was to create a precedent for Poor Law authorities all the land over.

Midwifery was another branch of the nursing art which Florence Nightingale sought to reform. She published in 1871 “Introductory Notes on Lying-in Hospital”; and, in 1881, writing on this subject to the late Miss Louisa M. Hubbard, who was then projecting the formation of the Matrons’ Aid Society, afterwards the Midwives’ Institute, she said, referring to these “Introductory Notes”:-

The main object of the “Notes” was (after dealing with the sanitary question) to point out the utter absence of any means of training in any existing institutions in Great Britain. Since the “Notes” were written next to nothing has been done to remedy this defect.…The prospectus is most excellent.…I wish you success from the bottom of my heart if, as I cannot doubt, your wisdom and energy work out a scheme by which to supply the deadly want of training among women practising midwifery in England. (It is a farce and a mockery to call them midwives or even midwifery nurses, and no certificate now given makes them so.) France, Germany, and even Russia would consider it woman-slaughter to “practise” as we do.

No less keen was her interest in rural hygiene. The need of observing the laws of health should, she thought, be directly impressed on the minds of the people, and to this end she organized a health crusade in Buckinghamshire in 1892, employing-with the aid of the County Council Technical Instruction Committee-three trained and competent women missioners, who were to give public addresses on health questions, following up these by visiting cottagers in their own homes and giving them practical advice.

WRITINGS

Further evidence of Florence Nightingale’s activity and beneficent efforts is afforded by the series of books, pamphlets, and papers that came from her pen. In 1858 appeared her “Notes on Matters affecting the Health, Efficiency and Hospital Administration of the British Army,” a volume of 560 pages, in which, “so far as the state of my health,” she writes, “has permitted me,” she makes an exhaustive review of the defects that led to the “disaster” at Scutari, and discusses in the most thorough and lucid manner the various points calling for consideration in regard to the management and efficiency of army hospitals. The value of this work, still great, was simply incalculable at the time it was first issued. In October, 1858, Miss Nightingale contributed two papers to the Liverpool meeting of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science on “The Health of Hospitals” and “Hospital Construction.” In 1860 she published “Notes on Nursing.” So popular has this work become by reason of its thoroughly practical hints, given in the clearest possible language, that some 100,000 copies of it are said to have been sold. For the Edinburgh meeting of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science, held in 1863, Miss Nightingale contributed a paper on “How People may Live and not Die in India”; and she followed up the same subject, when the association met at Norwich, in 1873, with a paper on “Life or Death in India,” this paper being subsequently reprinted with an appendix on “Life or Death by Irrigation,” in which considerations arising out of the Bengal famine are discussed more especially from the point of view of the paramount necessity of combining drainage with irrigation.

CLOSING YEARS

In these various ways one sees how Florence Nightingale, though a bedridden invalid and well advanced in years, was still ever ready, as she had been throughout life, to devote her energies to promoting the practical well-being of her fellow-creatures. What with writing papers, pamphlets, and letters, receiving reports concerning the many movements in which she was interested, and dealing with communications from Governments, authorities, and others all the world over, she was, even in the closing years of her life, essentially a hard-working woman. How great, indeed, were the demands made upon her time is well shown by a letter addressed by her on October 21, 1895, to the Rev. T. G. Clarke, curate of St. Philip’s, Birmingham, and local secretary of the Balaclava Anniversary Commemoration. In the course of this letter she said:-“I could not resist your appeal, though it is an effort to me, who know not what it is to have a leisure hour, to write a few words”; and she added:-“I generally resist all temptations to write, except on ever-pressing business. I am often speaking to your Balaclava veterans in my heart, but I am much overworked.”

Yet, among all these manifold claims upon her attention, she never forgot that unpretending “Home” in Harley-street, W., over which she was still presiding when she went out to the Crimea. In The Times of November 12, 1901, she appealed for further support for this institution, declaring that it was:

Doing good work-work after my own heart, and I trust, God’s work. There is [she continued] no other institution exactly like this. In it our governesses (who are primarily eligible), the wives and daughters of the clergy, of our naval, military, and other professional men, receive every possible care, comfort, and first-rate advice at the most moderate cost.…Every one connected with this home and haven for the suffering is doing their utmost for it and it is always full. It is conducted on the same lines as from its beginning, by a committee of ladies, of which Mrs. Walter is the president, and she will be glad to receive contributions at 90, Harley-street, W. I ask and pray my friends who still remember me not to let this truly sacred work languish and die for want of a little more money.

On the occasion of her 84th birthday, in May, 1904, Miss Nightingale (who had already received the Red Cross from Queen Victoria) had conferred upon her by King Edward the dignity of a Lady of Grace of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem. October 21, 1904, was the jubilee of the memorable expedition on which she set forth in 1854; to few great reformers had the mercy been vouchsafed of seeing within their own lifetime results so striking and so beneficial as those that had followed the noble efforts of “The Lady with the Lamp”; and the congratulations she received on the occasion of her jubilee were but a sample of that universal veneration she had won.

Further recognition of the value of her life’s labours came to Miss Nightingale with the announcement in the London Gazette of November 29, 1907, that the King had been graciously pleased to confer upon her the Order of Merit, she being the only woman upon whom this exceptionally distinguished mark of Royal favour has been conferred. On March 16, 1908, Miss Nightingale received the honorary freedom of the City of London, an honour which had been conferred upon only one woman before-namely, the late Baroness Burdett-Coutts. Owing to her advanced age, Miss Nightingale was unable to be present at the Guildhall to receive this mark of distinction, and her place was taken by a relative. At her own request the money which would have been spent on a gold casket was devoted to charity, the sum of 100 guineas being given instead to the Hospital for Invalid Gentlewomen; and the casket presented to Miss Nightingale was of oak.