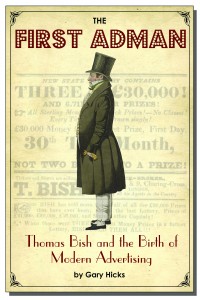

The First Adman

By 1821 Vauxhall Gardens had lost their lustre. Takings were down, and the attractions had become stale. Cash-strapped customers were getting less value for money from their food and drink. ‘ Supper was a perfect abomination,’ recalled Lord William Lennox, military aide to the Duke of Wellington. Fortunately, an entrepreneur who had pioneered modern advertising in order to sell tickets in the national lottery was looking for a moneymaking opportunity.

Thomas Bish (1779 – 1842) was a strange mixture of idealist and spiv who managed to be expelled from both the House of Commons and the Stock Exchange in the same year, 1826. Returning to Parliament as MP for Leominster in 1832, he formed an unlikely alliance with the Irish radical leader Daniel O’Connell to campaign for Irish reforms. Bish was also a marketing genius, hiring the essayist Charles Lamb as copywriter and George Cruikshank as illustrator. Techniques Bish pioneered included spin-doctoring, graphic design, the use of modern typography, direct marketing and even early market research.

Following a campaign led by William Wilberforce, Parliament decided to do away with the State lottery from 1826 onwards. The slave-trade abolitionist thereby abolished an important part of Bish’s income as principal broker for the lucky draw. Restoring the sparkle to a fading pleasure ground promised to make up some of the lost cash. In 1821, therefore, with his old business cronies Frederick Gye and Richard Hughes (a music lover), Bish bought the Vauxhall Gardens lease from the Tyers family. The partners paid £30,000 (£1 million today) topped up by yearly ground-rent payments averaging £1800 (£60,000). An option to buy all the property was exercised in 1825, but Bish dropped out.

The grand relaunch was planned for the 1822 season as most of the attractions for 1821 had already been arranged. The resourceful Bish now pulled a marketing masterstroke. For decades the newly-enthroned King George IV, first as Prince of Wales and then as Prince Regent, had used Vauxhall for amorous adventures. When George ascended the throne in 1820, Bish swooped and the new monarch readily accepted an invitation to become the Gardens’ patron. Thus, an amusement park could be renamed The Royal Gardens, Vauxhall, and a title that Bish insisted appear on every entry ticket, programme, advertisement, handbill and supper menu. The proud new proprietors also exploited the royal connection by staging galas attended by most of fashionable London. Starting with the disappointing firework displays (‘They are not equal to Tivoli’ complained society beauty Lady Calvert, in her 1819 diary), Bish and his partners set about rebranding, reinventing, redecorating and reviving. The ‘Tivoli’ Lady Calvert meant was the amusement park in Paris on the site of today’s Saint-Lazare station. This Tivoli opened in 1795 with beautiful gardens, whose attractions ranged from a fairground to rare plants and many other attractions including a fairground. A number of public amusement parks were named after it, notably Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens (1843).

Bish sent Vauxhall’s firework specialist Madame Hengler (real name Sarah Field of Lambeth) to Paris to pick up tips from the experts who staged the spectaculars that so delighted King Louis XVIII. Sarah had graduated to putting on her shows from tightrope walking while juggling clay tobacco pipes and swallowing giant live grubs. As Madame Hengler, she was appointed “Pyrotechnist to His Majesty” with the job of organizing fireworks displays on Royal birthdays, and is celebrated in a Thomas Hood ode as ‘Starry Enchantress of the Surrey Garden! She was paid huge bonuses to create new novelties such as her innovative Green Fire “unknown to any other Artist”, a Mine of Snakes, an Egyptian Obelisk, and the Grand Girandole Wheel. To the delight of the crowds, George IV himself occasionally brandished the flaming torch to fire up these set pieces.

Sarah’s death, in 1845, was no less dramatic than her life. For 50 years she had sorted and stored fireworks in her own home at 4 Asylum Buildings, Westminster Road. One dark October night a whole batch went off. Within seconds, a sheet of flame engulfed the premises. The former tightrope walker, by then nearly ninety years old and enormously corpulent, was unable to raise herself to her bedroom window and jump. Crying out piteously, she perished in the flames like a grotesque female Guy Fawkes on a gigantic bonfire, a spectacularly fitting if gruesome end to a remarkable career.

An advertising blitz preceded the opening of the triumphant first season of ‘Royal Vauxhall Gardens’ on 3 June 1822, an opening that won rave reviews in the press. The crowds, curious to experience the new Vauxhall, poured in. Profits soared, allowing bigger and better attractions to be bought as Bish continued to invest heavily in promotion, paying a £100 a week for printing and advertisements alone. The following 1823 season pulled in a record-breaking attendance of nearly 140,000.

Overseeing the amusements was an eccentric Master of Ceremonies, C.H. Simpson, who greeted visitors with exaggerated obsequiousness and wore an eighteenth- century frock-coat with black silk knee-breeches and carrying a tasselled and silver-headed cane. Simpson was therefore an obvious target for violent drunks, and Bish, who made a point of patrolling the illuminated avenues on busy nights, was particularly protective when rowdies picked on this natural victim. Late one Monday evening in July 1822, three London drapers, the brothers William and John Creed, and Edmund Lancaster entered the gardens dressed in the costumes of Corinthian Tom, Jerry Hawthorn and Bob Logic, the three central characters in the stage version of Pierce Egan’s bestseller Life in London, then running to packed audiences at the Adelphi Theatre off The Strand. Drunk on punch and wine, the three drapers roared around the walks so persecuting Simpson that Bish had them locked up. At the subsequent court hearing Bish declared ‘the proprietors are resolved to have the gardens most vigilantly watched’.

As well as his hands-on approach, Bish the lottery man was gifted with a broad strategic sweep, a rare combination that was to make his fortune. An anonymous note of the period credits him with upgrading “Orchestra, Ballet, Theatre etc.” Culturally, that went way beyond the new, well-received, vaudeville acts. Plays and operas specially designed for the gardens were commissioned and world-class concerts organized.

Fifteen years later Bish again came to the rescue. In 1837 Robert Cocking chose the Royal Gardens Vauxhall for his attempt to be the first Englishman to make a parachute descent from a hot-air balloon, Vauxhall Gardens’ Royal Nassau. Cocking’s rackety contraption failed to open and Cocking plunged to his death, landing in a field in Lee. To combat acres of negative newspaper publicity, Bish and other celebrities later took off from Vauxhall in the Nassau. The stunt worked, but only just; Nassau ended its flight comically marooned atop a tall elm tree in Twickenham.

Gary Hicks

Kennington resident Gary Hicks’ book The First Adman. Thomas Bish and the Birth of Modern Advertising is published by Victorian Secrets. Available through www.amazon.co.uk