The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. “Edward, prince of Wales, the Black Prince.” New York Public Library Digital Collections

The Duchy of Cornwall owns much of Vauxhall and Kennington, which makes the local landlord HRH Charles, Prince of Wales. One of the royal heir’s other titles is Duke of Cornwall. The first Duke was a Vauxhall resident as well as landlord. This is short-lived warrior Edward of Woodstock (1330–1376), who was invested as Prince of Wales in 1343 and has gone down in history as the Black Prince.

Lambeth Archives describes this unattributed engraving, possibly late-Victorian, as ‘an idealised view’ of the ‘ancient royal palace at Kennington, birthplace of Richard II and favourite home of Edward, the Black Prince’, adding that ‘the palace was demolished in the reign of James I and replaced with Kennington Manor, the residence of Charles I when Prince of Wales’. Image © London Borough of Lambeth, courtesy of Landmark

In a new biography The Black Prince, South Londoner Michael Jones questions whether the Edward was nicknamed Black because of his alleged brutality towards civilians and captured enemy soldiers. As Karen Coke points out in her review of The Black Prince (below), Edward was particularly ‘blackened’ by the horrendous slaughter of civilians during the siege of Limoges (1370). Yet contrary to an account by the French chronicler Froissart, the killers were not Edward’s English troops but the army of his French opponent, the Duc de Berry. Edward seems neither to have been particularly cruel by the standards of his time nor to have worn black armour, although as Michael Jones points out, the backdrop to Edward’s tournament badges on his tomb at Canterbury Cathedral is black.

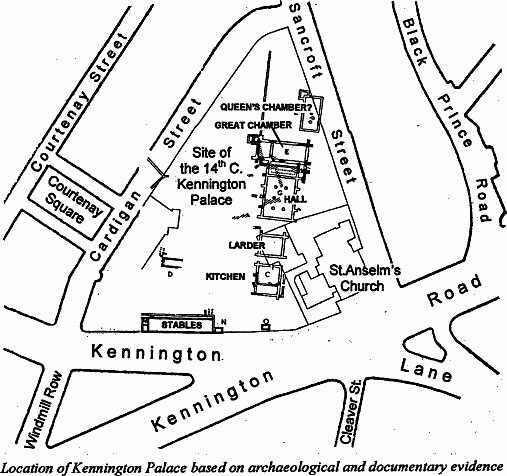

Site of Kennington Palace

In his lifetime, Edward was known after his birthplace as Edward of Woodstock. The Black Prince tag did not surface until about 150 years after his death. It is memorably voiced about 1599 by Shakespeare in Act 2, Scene 4 of his Henry V, which can be read as suggesting that the warlike Edward was ‘black’ to his opponents in battle because he gave them so many black days, notably Poitiers (1356). Shakespeare has the French king Charles VI fear for the outcome of the Battle of Agincourt (1415), because Henry is a descendant of Edward, who distinguished himself at the humiliation of the French at Crecy (1346):

Witness our too much memorable shame,

When Cressy battle fatally was struck,

And all our princes captured by the hand

Of that black name, Edward, Black Prince of Wales.

Vauxhall’s six-year-old landlord

Edward of Woodstock became the first Duke of Cornwall when he was just six years old. The main residence near London that came with the new duchy was a manor house at the Kennington end of what is now Black Prince Road. Edward celebrated his victory over the French at Poitiers and the capture of the French King John (1356) by tearing down the Kennington manor house to build a palace near Kennington Cross in the triangle formed by Kennington Lane, Sancroft Street and Cardigan Street. He sired at least four illegitimate children, mostly, it seems before his marriage in 1363 to his cousin Joan, Countess of Kent. Limoges (1370) was Edward’s last engagement. He had to be stretchered to the scene, worn out by constant campaigning and terminally ill (possibly with amoebic dysentery).

In 1531, King Henry VIII ordered much of Kennington Palace to be dismantled and lugged across the Thames to Westminster for the building of a new royal palace, Whitehall, now also long gone. The track along which the Kennington Palace timber, masonry and brick and stone masonry was carted to the river was renamed ‘Black Prince Road’ in 1939.

Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. “Character sheet for the drama Edward the Black Prince” New York Public Library Digital Collections

Black mark, Froissart

Review by Karen Coke

Michael Jones excels at action-packed exciting battlefield descriptions. You can feel the blows, smell the blood, hear the roar of men and sense the agony of dying horses. From meticulous preparation to the final victorious planting of the standard, the narrative is driven along like a battle-charge bringing to life the story of that most charismatic knight the Black Prince, Edward of Woodstock.

From the outset he was a prince who knew how to inspire his men. At Poitiers, aware the outcome was stacked against him, Edward rallied his men with a defiantly ringing speech, ‘in the name of God and St George’. In spite of being outnumbered by three to one, the English force beat the French, thanks to cunning, bravado and tactical brilliance. We are left wondering why Poitiers, unlike Agincourt, is not enshrined as a legend of English warfare. Yet amid the carnage of a military life, there are flashes of humour. In 1338 troops of Edward’s father, Edward III, besiege Dunbar Castle. It is held by Agnes, Lady Dunbar, for her husband the Earl of Dunbar and March is away. The English siege catapults pound the castle with huge stones. In full view, Lady Agnes taunts the English by sending one of her ladies-in-waiting to dust down the castle wall. Dunbar threatening to become a PR disaster, the siege is called off.

Michael Jones has scoured contemporary and recently-discovered sources to reach the man beyond the legend. Edward was courteous, generous, sometimes profligate, and undoubtedly courageous but, like many of his contemporaries who breathed the refined air of the chivalric code, he struggled to negotiate a life of contradiction: How to be the perfect prince while at the same time avoiding accusations of vainglory, to be the invincible warrior yet no threat to his father’s crown, to reconcile a profound spirituality with the horrors of warfare, and remain aware, always, of the turning of the fickle Wheel of Fortune.

We share the prince’s camaraderie with his fellow knights, his loyal if complex relationship with his father Edward III, see clearly the king he might have become had illness and death not intervened, admire the simplicity of his faith and ultimately are both saddened and uplifted by his bearing in the final hours.

The chevauchée, the ‘scorched earth policy’ that was pursued by the Black Prince and his father, was in itself a brutal yet accepted aspect of medieval warfare and Jones reminds us that though fierce in battle the prince was invariably honourable in victory. Yet the prince has suffered from a bad press and this is largely due to the 14th-century French chronicler Jean Froissart whose Chroniques, his account of the Hundred Years War, were widely read and hugely influential throughout Europe in the following centuries.

In 1370, the English stronghold of Limoges had surrendered to the French Duc de Berry. Edward and his army regained the city only to discover the retreating French garrison had massacred 3,000 of its population. The exact numbers of civilians killed at Limoges, and why, is still a subject of debate but whatever the truth, it provided an unmissable opportunity for the French. A calculated attempt to ‘blacken’ Edward of Woodstock’s name, Jean Froissart’s reassignment of the blame to the English prince and his armies for the massacre at Limoges was a last-ditch attempt to succeed with propaganda what the French armies had been unable to achieve by force.

Determined that ‘it is time to dismiss this slur by Froissart’, Michael Jones memorably fleshes out this historical figure, Edward the Black Prince, as a man who should now be judged more kindly.

The Black Prince by Michael Jones. Published by Head of Zeus, £30.

KAREN COKE is currently researching the early Tudor painter Lambert Barnard, has contributed to several academic publications and is the author of the brief guide Lambert Barnard, Chichester’s Tudor Painter (Chichester, Dean and Chapter of Chichester Cathedral, 2014).