In the late 1950s Vauxhall was home to Claudia Jones, one of the most important figures in black British history during perhaps her most creative period, when she founded the West Indian Gazette, Britain’s first major black newspaper. Sean Creighton looks at the impact of her work.

Claudia Jones was born in Trinidad on 21 February 1915. After the collapse of the island’s cocoa trade, she and her family moved to Harlem, New York, where they lived in poverty. Throughout her life she suffered poor health—tuberculosis and heart problems—caused in part by childhood deprivation. Her mother, a garment worker, died when Jones was 13. Although Jones excelled at school, she was too poor to continue her formal education.

While working for local businesses she started to write for a Harlem publication. She also joined the Young Communist League, rising to national level, and worked as a journalist and editor on the Party’s Daily Worker, theWeekly Review and the YCL monthly journal. Between 1945 and 1953 she took leading roles in the US Communist Party on negro affairs [contemporary term], women and peace.

From 1948, persecuted by US Government because of her Communist affiliations, she was imprisoned four times. The Party and friends such the actor, singer and civil rights activist Paul Robeson and his wife Eslanda Goode ran campaigns to support her, but she eventually lost the fight and was deported in 1955 as a British subject.

In England, she stayed with other US Communist exiles but it was through her membership of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) that she came to live in a two-bedroom flat at 6 Meadow Road owned by Hewlett Johnson, the so-called Red Dean of Canterbury (his nickname arose from his support for the Soviet Union). She shared it for a time with her partner Manu Manchanda, an activist involved with the Indian Workers’ Association. Jones’s relationship with the CPGB was fraught. Despite complaining of racism and sexism, she remained a member until her death.

During this period of Jones’s life, she focused on campaigning against racism in housing, education and employment, issues that had come to the fore with the growth of the West Indian post-war immigration. This led to her founding, in March 1958, the West Indian Gazette, which initially had an office at 250 Brixton Road, later moving to Station Road, Loughborough Junction. She took on the role of editor, with Manchanda as managing editor, and the novelist Donald Hinds, who had been working as a bus conductor because he could find no other suitable employment, as city reporter.

The Gazette was initially published monthly, although its appearance was uneven, hampered by lack of funds to pay the printer, but by 1959 it had reached a circulation of 10,000. In order to ensure a broad readership, Jones designed its editorial mix to include arts and beauty, as well as poems and short stories alongside serious political features.

In the late summer of 1958, riots occurred in Notting Hill in west London (and later also in Nottingham), during which West Indians fought back against attacks by neo-Nazis. To raise money for the legal costs of the West Indians arrested, and to promote and share Caribbean culture, Jones set up an indoor cultural event called ‘Claudia’s Caribbean Carnival’.

The first carnival was held in January 1959 at St Pancras Town Hall and was broadcast by the BBC under the slogan ‘A people’s art is the genesis of their freedom’. The following year the line-up included the calypso singer Lord Kitchener, the former RAF pilot, actor and singer Cy Grant, the novelist Samuel Selvin (The Lonely Londoners) and the singer Nadia Cattouse. The beauty contest, which Jones planned as attempt to promote pride in being black, was judged by the Bajan writer George Lamming (In the Castle of My Skin). In a foreword to the 1960 souvenir brochure, Claudia Jones wrote that ‘our Carnival [symbolizes] the unity of our people resident here and of all our many friends who love the West Indies’.

Jones worked in many alliances, such as the Inter-Racial Friendship Co-ordinating Council, along with Amy Ashwood Garvey and Pearl Connor, which was formed after the racist murder of the Antiguan Kelso Cochrane in Notting Hill in May 1959. Her friend Eslanda Robeson spoke at Cochrane’s memorial meeting at St Pancras Town Hall. She also supported the Movement for Colonial Freedom, which from 1959 ran an African Freedom Day concert, and the Boycott Movement, which became the Anti-Apartheid Movement.

With The Gazette constantly in debt, Jones became unable to pay her rent on the Meadow Road flat and in 1960 she moved to North London. In the campaign against the Commonwealth Immigration Act of 1962 she worked with Labour MP Fenner Brockway and set up the Afro-Asian Caribbean Conference. Norman Manley, the Prime Minister of Jamaica, attended the inaugural meeting.

In August 1963 she was involved in activities to support the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom at which Martin Luther King made his ‘I Have a Dream’ speech. The next year she received a visit from King, who was in Europe to receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

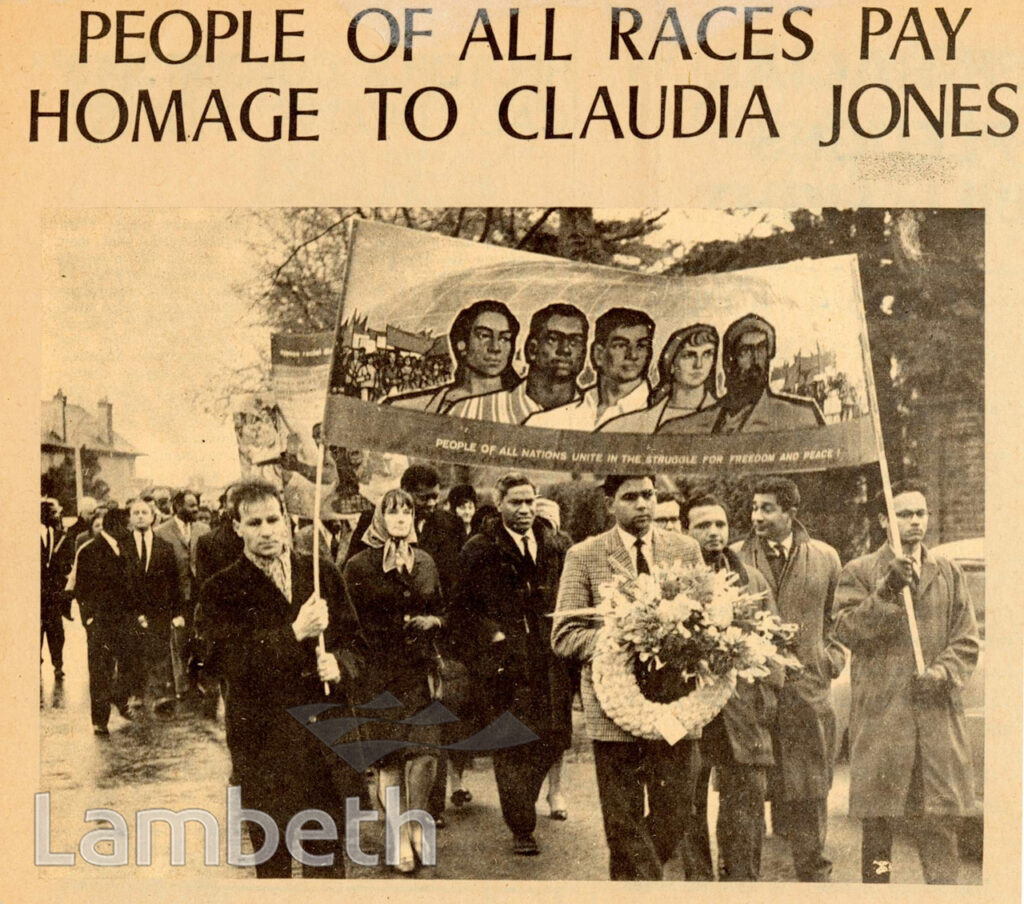

Jones died of her chronic illnesses in north London in December 1964 at the age of 49. Her funeral service included a recorded message from Paul and Eslanda Robeson, and Nadia Cattouse closed by singing ‘We Shall Overcome’. She is buried in Highgate Cemetery, next to Karl Marx. Among those taking part or sending messages at a second memorial held at St Pancras Town Hall in February were the Algerian Ambassador, the Ghana High Commissioner, Lord Brockway, Oliver Tambo of the African National Congress, Nadia Cattouse and the folk singers Ewan McColl and Peggy Seeger.

Organised by community activists Rhaune Laslett and Andre Shervington, the Carnival continued, becoming an outdoor event in 1966, and is now held yearly over the August bank holiday weekend in the streets of Notting Hill and Kensington. Despite conflict with racists and police, it developed into a London cultural institution, with up to two million people attending.

The Gazette closed in 1965, eight months after Jones’s death. Her dynamism, editorial innovation, and humanity made it a pioneer of the black press in Britain. Her most remembered legacies, the Gazette and the Carnival, were immensely important in creating a shared Caribbean identity amongst West Indian immigrants in Britain and in highlighting and fighting racial discrimination.

Further Reading

Marika Sherwood (1999). Claudia Jones. A Life in Exile. Lawrence & Wishart.

Carole Boyce Davies (2008). Left of Karl Marx. The Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones. Duke University Press.

Carole Boyce Davies (ed.) (2011). Claudia Jones: Beyond Containment: Autobiographical Reflections, Essays, and Poems. Ayebia Clarke Publishing.

Black Cultural Archives: A History of Notting Hill Carnival

The West Indian Gazette: A symbiotic dialogue between the local and the global

Claudia Jones and the ‘West Indian Gazette’ by Donald Hinds.