Naomi Clifford, with research assistance from Paul T. Klein, explores the life of Susanna Meredith, a 19th-century pioneer in the aftercare of women prisoners.

“Your petitioner humbly beg [sic] for mercy. She has done 14 years and 9 month of her life sentence and beg your Lordships to forgive her the remainder of it that she may return to her own country to see and help her own father in his old age or if your Lordship like to send her to London to Mrs Meredith she will work for an honest living.”

M.D., a Belgian prisoner at Woking Women’s Convict Prison in 1886, petitions for early release from a life sentence for murder.[1]HO144/11984/47.

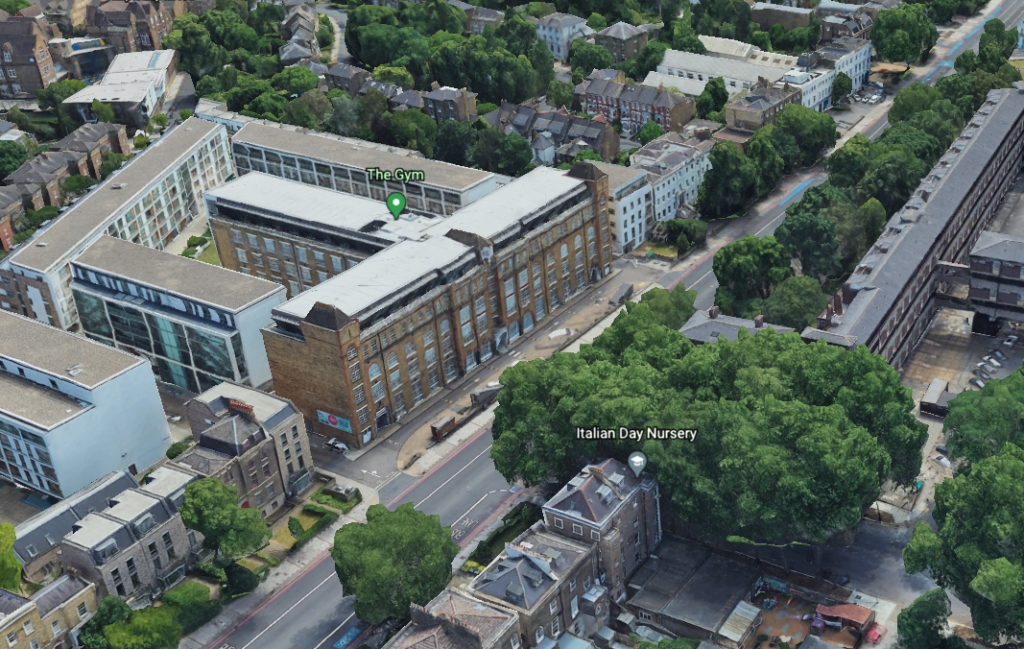

Next time you find yourself in the upper end of Wandsworth Road, stop near Sainsbury’s and look across the road towards the railway bridge. Half-close your eyes and picture, in place of the Strawberry Star tower, a shabby Victorian building set back from the road. You might be able to catch the shouts and raucous laughs of women working in the back of the house, and on the air, a mix of starch and bleach. You are imagining the Nine Elms Laundry, which stood there for most of the last quarter of the 19th century, an extraordinary enterprise staffed by former prisoners and run by an extraordinary woman: Susanna Meredith.

Mrs Meredith was born Susanna Lloyd in Cork, Ireland in 1823, the eldest daughter of Farmar Lloyd, the governor of Cork County Gaol. At the age of 17 she married William Lambert Meredith, a doctor ten years her senior, with whom she shared a fervent Protestant faith. He died seven years later. Childless, she threw herself into philanthropic work. In Cork she became involved in an industrial school for girls in lacemaking, and in London—she and her widowed mother moved there in 1860—she edited The Alexandra, a magazine advocating greater employment opportunities for women.[2]The Alexandra Magazine, whose aim was to reach a readership of women already working for a living, closed in 1856 after about a year of publication. See: Sheila Herstein (1993). The Langham … Continue reading However, it was for her work with women former prisoners in south London that she was best known.

Dismayed at the misery she found when she started visiting women incarcerated in Brixton Prison (then for women only), she and some like-minded women established the Prison Mission.[3]In 1864, the social reformer Mary Carpenter’s book Our Convicts alerted the public to the appalling conditions for women prisoners at Brixton Prison. Every morning two volunteers stood by the gates of London prisons housing women to await those released that day. Some, tempted by the prospect of tea and food, were persuaded to accompany the ladies to rooms nearby. They may have relished the thought of a Bible reading and prayer but it is more likely that they were attracted by the offer of work.[4]E.C. Wines (1873). Report on the International Penitentiary Congress. Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 237-8.

The work was sewing, at which few of the women excelled and which brought the Mission pitifully little revenue. Soon Mrs Meredith and her fellow volunteers had more ambitious plans.

“She has always maintained that the only way to wean a convict from evil ways and to help her to a respectable place in the world is to inculcate habits of industry.”

Mother’s Companion, 1 February 1895[5]p.8.

Female criminality

The Victorians were obsessed with crime and the “criminal classes”, and especially criminal women. The medieval view of ideal womanhood prevailed; women were designed by God to be naturally maternal, gentle, caring, loving helpmeets for men. By breaking the law of the land they also broke the laws of nature; they became, in effect, “unsexed” monsters. Although far fewer women committed crime than men (their crimes were overwhelmingly larceny or low-level violence, often connected with alcohol use) and fewer of them were imprisoned, those who did transgress were considered more morally depraved than men and, in general, deserving of harsher punishments.

When transportation ended in 1857 the government was faced with the problem of how to deal with the thousands of additional prisoners on its hands.[6]After the 1853 penal servitude act, only long-term transportation remained and that was abolished after the penal servitude act of 1857. A few convicts were transported after the … Continue reading The focus began to be on preventative measures, including ways to reduce the rate of recidivism. In almost every county there were Discharged Prisoners’ Aid Societies, licensed by the Home Office, whose aim was to find work and accommodation for convicts who had been released early under the ticket-of-leave system. While they were in the societies’ care they were still under sentence and could be returned to prison if they broke the terms of their release. In London the Royal Society for the Assistance of Discharged Prisoners, founded in 1857, operated a hostel for women at Russell House in Streatham where it trained them as domestic servants and helped them to emigrate to Canada or the United States.[7]Russell House was at 2 Mitcham Lane. It closed in 1888 when the premises were taken over by a Roman Catholic mission to fallen women.

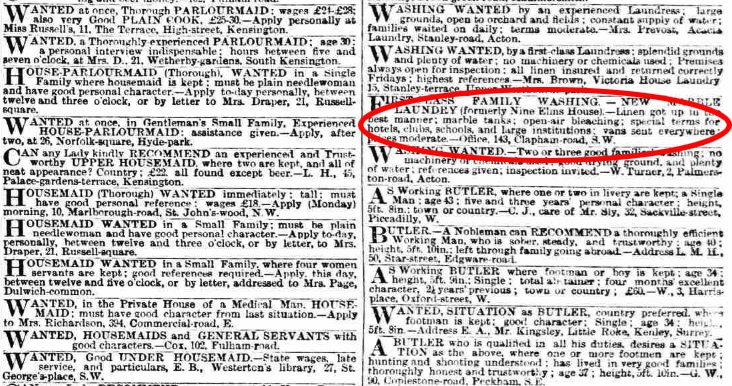

Mrs Meredith knew that placing female former prisoners as servants within households was bound to fail. Some of the women received weekly visits from the police, which would be unacceptable to any respectable householder, and there was also the fundamental issue of trust. “It would be well to make it generally known that only a very small percentage of women who have suffered penal servitude enter the domestic line of life,” she wrote in 1879. “They are usually incapable of such employment. Their way of getting an honest living is mostly confined to daily labour in such operations as women with characters for propriety can afford to refuse. Happily there is no lack of work accessible to convicted women, without their competing for domestic service. When they attempt this, it is usually with the aid of misdirected benevolence, or by false statements. It is unwise and unnecessary to place them in families. Their labour should be encouraged in other directions, under circumstances that provide for their special disqualifications.”[8]Evening Standard, 2 August 1879, p.2. With six other women, including her older unmarried sister Martha, Mrs Meredith set up a Discharged Female Prisoners Aid Society. The “other directions” Mrs Meredith had in mind was the Society’s own steam laundry, which would employ the women directly.

Laundries and rehabilitation

Laundries had played a role in punishment and rehabilitation since the 18th century, mainly housing so-called fallen women. The first Magdalene laundry, a Protestant institution, was established in Whitechapel in London in 1758. In the first half of the 19th century, Magdalene laundries were more like penitentiary workhouses. In Ireland, Catholic Magdalene laundries proliferated, and focused on recalcitrant teenagers and unwed mothers. Mrs Meredith’s operation, established in the late 1860s at Nine Elms House, 6 Upper Belmont Terrace, Wandsworth Road, was run on very different lines.

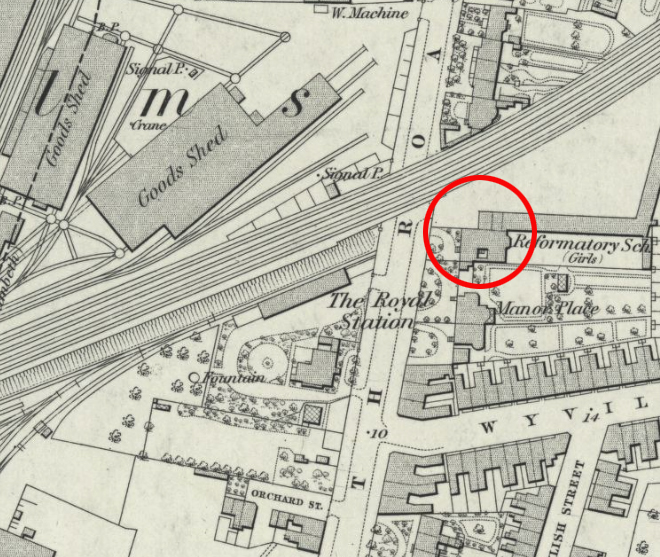

“Near to the Nine Elms Station,[9]Nine Elms Station was originally a goods stop but had been renamed Queen’s Station or the Royal Station in 1854 when it was converted for the use of the Royal family. It was demolished in 1878. and adjoining a bridge over the South Western Railway, is a brick house, standing in an enclosure, which has evidently seen better days…

The interior of the house is rather dreary and uninviting. There is no trace of luxury in the appointments. On the left-hand of the entrance ball is an uncarpeted room, in which several wooden chairs are placed in rows, giving to it the look of a school-house in a poor neighbourhood. Here instruction, chiefly of an elementary religious kind, is imparted to adult women, by ladies who eschew preaching or lecturing… At the back of the house, in what had formerly been a good-sized garden, are long iron sheds, in which clothes are disinfected, washed, mangled and dried. In the space left vacant the wet clothes are dried when the weather is fine; when rain falls they are dried in artificially heated chambers.”

Daily News, 25 July 1871[10]Daily News, 25 July 1871, p.5.

The women were governed by a set of rules, prominently displayed. They had to do all the work assigned to them, were not allowed alcohol, could not carry money on their person, and were forbidden from leaving the premises without permission. Breaking the rules could lead to instant dismissal, but the regime was firm rather than strict. Women who served a subsequent prison term were free to come back to the laundry, an important point of difference to other Discharged Prisoner Associations, and women remanded by the courts were also accepted. There was no religious barrier. Everyone was welcomed, whatever their denomination.

The women worked a ten-hour day from 8am to 6 in the evening for which they received a shilling and sixpence (18 pence) a day; fourpence was deducted for accommodation. Most lodged with local families, with a handful living at Nine Elms House. As you might expect, some women had difficulty conforming. They failed to turn up, or relapsed into crime, drink or sex work, or stole from the laundry. For example, in 1881 Ellen Davis was sentenced to five years penal servitude for taking two towels and some linen, “the property of Mrs Meredith”.[11]Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, 19 April 1881, p.4. We do not know whether Mrs Meredith approved of the harshness of the sentence.

Initially, the laundry was set up to be self-financing and washed for the well-off in the neighbourhood, but when the prisoners complained that their middle-class customers expected them to be grateful for the opportunity to wash for them, Mrs Meredith decided that they would instead take in the washing of the poor. Washing was often fraught with difficulty for poor households—they had few clothes or bedclothes and could not dry items fast enough to wear them. Families suffering infectious disease or cancer had their washing done for free. Mrs Meredith came to call this “washing for love”[12]W. G. Blaikie, The Princess Mary’s Village, Addlestone. The Sunday Magazine, 1875, p.420.

The 1871 census shows Mrs Meredith and her sister Martha living within walking distance of the laundry at 45 The Lawns, South Lambeth Road, with four domestic servants.[13]The National Archives; Kew, London, England; 1871 England Census; Class: RG10; Piece: 671; Folio: 73; Page: 17; GSU roll: 823327 By this time, she and Martha had started another ground-breaking initiative. Troubled by the lives of the prisoners’ children, the girls in particular, they wanted to offer them a permanent home away from London.[14]Sunday Magazine, op. cit. This was unprecedented. There was little official interest in the welfare of prisoners’ children, except when they became criminals themselves, and children under the age of six had no recourse to public funds. In 1870 with her friend Caroline Cavendish (1840-1925) Mrs Meredith started placing very young children with foster parents in the area around Chertsey, Surrey and a year later, with donations and government support, set up Princess Mary Village Homes for Girls at nearby Addlestone. The Homes were run on the cottage or “family” system, with each house-mother in charge of ten girls.[15]The establishment was named after Princess Mary Adelaide, Duchess of Teck, who cut the first turf. By 1880 the Homes were caring for around 175 girls.[16]The Star, 27 April 1880, p.4.

Often, the women whose children were being taken into care objected. “It is with great difficulty that we can prevail on these women to give their little girls out of their hands,” one of Mrs Meredith’s associates told the Daily News in 1871, blaming the women’s “cruel thirst for profit through their means” rather than maternal attachment. “The mothers are insensible to our sense of their guilt,” she went on. “Some smile at us; many are quite annoyed at our suggestions. Some have violently resisted our attempts to rescue their own daughters from defilement.”[17]The Daily News, op. cit.

In London the mission at Nine Elms House was expanding. The washing sheds were rebuilt in 1872 (they can be seen clearly on an OS map of 1894-6).[18]The laundry had moved to Stockwell by this time, and the rest of the site redeveloped. In 1878 a coffee hall and a reading room were added; they proved popular with local railway workers and their families.[19]Banffshire Journal and General Advertiser, 31 December 1878, p.3. A Wesleyan commissioner who visited in 1883 had mixed feelings about the operation, however. In a piece titled “Among the Sick and the Sinful” he described Mrs Meredith’s work as “one of the most beautiful and blessed manifestations of the power of the love of Christ”; but he found the plain brick building, reached via “dingy” Wandsworth Road, “dreadfully dull” and in need of brightening up. As he observed a volunteer read a story to about 30 women while they had their lunch—Mrs Meredith, ever the pragmatist, felt too much religion could defeat her aim of converting them—he came to the conclusion that “for the most part [the women] obviously belonged to the lower, if not the lowest class” and that “only one or two bore any traces of refinement.”[20]The Wesleyan-Methodist Magazine (1883), Series 6, Vol. 7, pp.142-149.

Appearances

The women’s appearance was of central importance to respectable society. Most people believed that if you looked evil you were evil and that attractive criminals were merely expert in hiding their criminal souls. In late 19th century two allied theories of biological determinism became increasingly influential. Physiognomy, the study of the correspondence between facial features or body structure and psychological characteristics, exposed women, especially criminal women, to lengthy discussions and analysis of their appearance and moral value. Female offenders, most of whom had lived chaotic lives marked by poverty, domestic violence and disadvantage, were judged against the unattainable standards of beauty of the middle and upper classes. Eugenics, the racist and classist theory that society would be improved with the elimination of those with weak or criminal genes, was boosted in Britain by, among others, Havelock Ellis (1859-1939). He believed that the physical markers indicated specific criminality: women who committed infanticide had more down on their faces and female thieves went grey more quickly, were uglier and exhibited signs of degeneracy in their sexual organs earlier than ordinary women. He had cause for hope, however—he thought female criminals so disgusting that men would not procreate with them and the criminal classes would eventually disappear.[21]Lucia Zedner (1991). Women, Crime, and Penal Responses: A Historical Account. Crime and Justice, Vol. 14, p.338.

Everything about the physical state of criminal women was scrutinised for clues to their inner character. Journalists visiting the laundry felt that their readers were owed descriptions of them. “All have an animal look in their eyes,” wrote the Daily News’s correspondent in 1871. “A heaviness of feature is common to them all… If the faces of these women were dyed a copper-colour, and if they were dressed in nondescript garments of a female Ute, or Shoshone Indian, they would pass for genuine savages. In reality they are not much better.”[22]Daily News, op. cit.

In her 1881 A Book About Criminals,[23]Published in 1881 by James Nisbet (London) Mrs Meredith acknowledged that the bodies of criminals were “public property.” “His [the criminal’s] likeness may become a carte de visite at police stations, an illustration in the ‘black book’ of the Home Office, a photograph in the album… of the Discharged Prisoners’ Aid Society, and a ‘waxwork’ figure, life size’ at Madame Tussaud’s. There is great importance attached to his appearance, and no less to his deed, and their penalties.” Unusually for her time, although she absorbed some of the prevailing thinking about criminal heredity, Mrs Meredith, did not see the women as the sum of their physical parts. She believed that, by accepting God, criminals had the potential for improvement in both body and soul, and she seemed to be achieving good results. The laundry was employing about 200 women a year, and attracting donations from across the country.

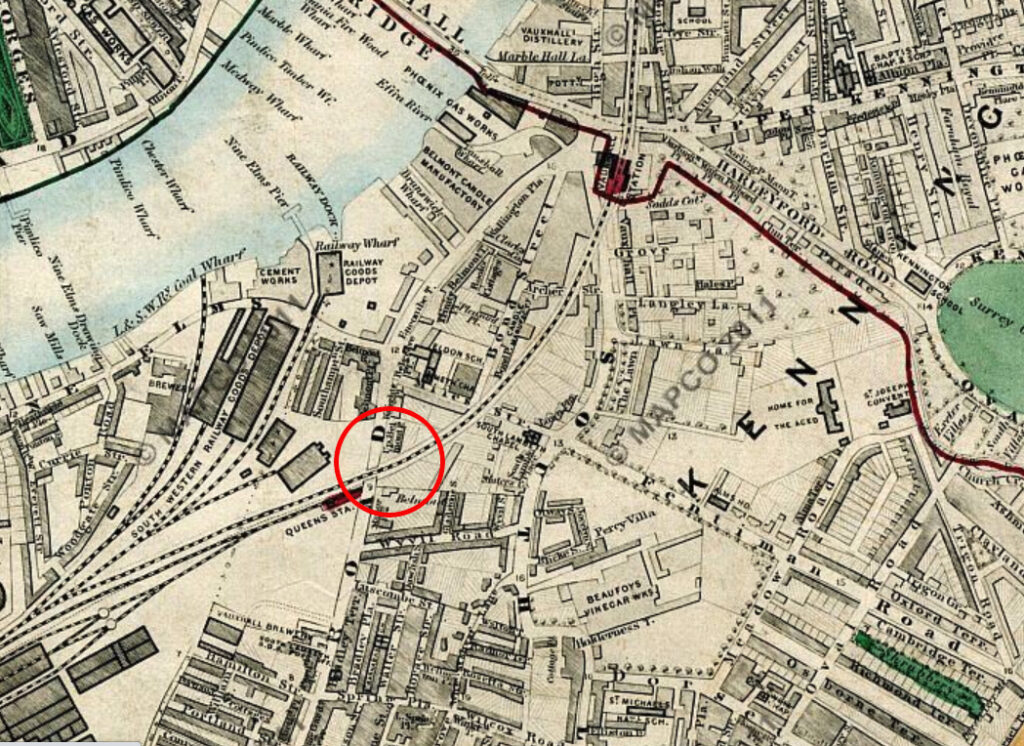

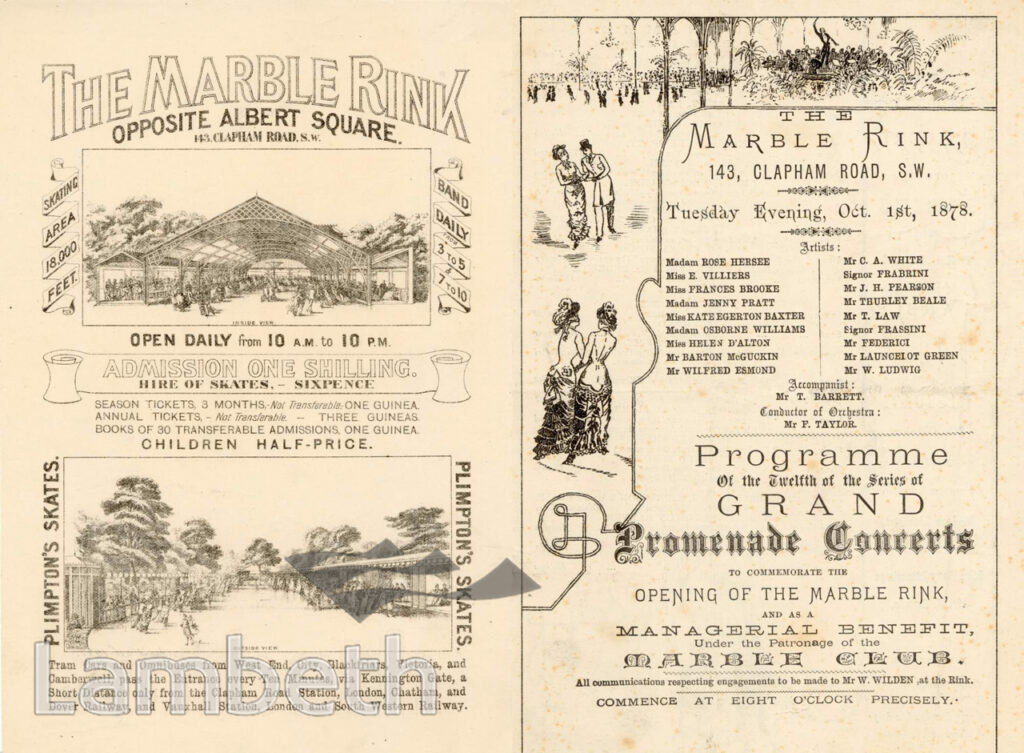

Its success meant that it was in constant need of funds. By 1887 there were plans to sell Nine Elms House and move the laundry to 143 Clapham Road, just under a mile away.[24]The Daily News, op.cit.; based on the advertised auction of lots when the laundry closed we can speculate that the move was prompted by a need to mechanise the laundry operation. The new location was on the site of the Marble Skating Rink, an iron building with a floor of polished white marble which had opened in 1876 and closed after only seven years of operation.[25]Evening Standard, 2 March 1883, p.7; Rugby Advertiser, 27 October 1880, p.2. In order to survive the venue offered diverse entertainments including music concerts and bicycle races which led to … Continue reading

The Marble Laundry

We have not been able to find any images of the Marble Laundry, as it came to be known, but a description by Anne Beale was published in 1891 in the Newbury House Magazine (“for churchmen and churchwomen”). She wrote of its “spacious buildings with high glazed roofs, and fitted with all the modern steam appliances”; there were also long ironing rooms and disinfecting troughs (they were still taking in the washing of the sick). Beale also wrote of the ethos of the laundry. The workers were a “floating population” who might come and go, but no woman was turned away. Those unable to do laundry work were given plain needlework or sewed slippers for sale.[26]Anne Beale, Prison Missions, Newbery House Magazine (1891), Vol. 4, pp.718-724.

The site was vast and accommodated Mrs Meredith’ own home, where she lived with her sister, and the headquarters of all of Mrs Meredith’s other organisations—the Addlestone Homes, a mission to Palestine and a charity sending out Christmas letters to thousands of prisoners across the world. The skating rink, an iron structure, had earlier been converted into a conference hall used by local organisations for mass meetings—a “Divine Service for the People” held every Sunday at 11am with Sydney Gedge, a lay preacher, was typical.[27]South London Chronicle, 1 August 1885, p.4.

In 1885, before she moved the laundry, Mrs Meredith had started using the bar of the conference hall to host an outpatients clinic (known as a dispensary) for poor women and their children. To run it, she hired a newly qualified doctor from Manchester, Annie McCall (1859-1949).

“Inside [the Conference Hall], Mrs. Meredeth [sic] and I worked happily together. I was a doctor; she was a social worker with wide interests and of Irish extraction… When slight differences arose between us, as they were bound to do, Mrs. Meredeth, with her liberal attitude to life, left me to pursue my way.”

Annie McCall remembers her work with Mrs Meredith.[28]Patricia Barrass (1950). Fifty Years in Midwifery: The Story of Annie McCall, M.D. London: Health for All Publishing Co, pp.37-41.

Dr Annie McCall

Mrs Meredith chose well. Annie McCall went on to have an incalculable influence on the health outcomes of pregnant mothers in south London and on obstetrics practice worldwide. Although she and Mrs Meredith had many differences of opinion and parted ways in 1887 after 18 months of collaboration they remained on good terms. [29]Dr McCall moved the outpatients department to her own home a few doors away at 131 Clapham Road. It subsequently moved to Fentiman Road (exact location unknown), then to McCall’s new address at … Continue reading “She was a woman of great parts,” wrote McCall. “Her story is significant in the evolution of some of our more modern social attitudes, and I have no doubt that it will be embodied in other records of the times through which she passed.”

Mrs Meredith left a body of writing, numerous pamphlets and a handful of published books, all of it underpinned by her Christian ethos. Laundry is gruelling labour, requiring strength and skill, but she and her associates saw it not as punishment but as opportunity. For the women, it was time away from life on the streets, in some cases away from an abusive partner, with access to food, shelter and medical care. She helped thousands of women, and her efforts prevented many from reoffending and returning to prison. At one of the Mission’s last annual meetings it was reported that in 1899 247 women had been received at the laundry on Clapham Road. Mr Justice Bruce, the chairman, made the point that “Prison at the best, though of course punishment of the crime was absolutely necessary, was not a good reformatory, and it was well that other influences should be brought to bear on those who had the misfortune to be imprisoned.” He blamed alcoholism for much of the criminality of women and advocated treatment centres to help them.[30]Morning Post, 18 June 1900, p.6.

In all of her endeavours, Mrs Meredith’s kindness come through strongly. The life prisoner whose quote is at the start of this piece had endured years of the exacting regime at Woking Women’s Convict Prison after committing a single and catastrophic act of violence that had taken a life and ruined her own. She was probably yearning for some of that kindness above anything else.

Legacy

In October 1901, Mrs Meredith died aged 78, at Woburn Hill, Addlestone, leaving an estate of £1,200 to her sister. She was buried at Brookwood Cemetery.[31]Morning Post, 20 December 1901, p.5. The Marble Laundry had already closed. Everything, the steam calendars, box mangles, hydro, engines, boilers, rotary washers, drying room fitters and ironing tables, was sold off at auction. A printworks was opened on the site two years later. The Princess Mary Homes at Addlestone kept going, expanded its intake to older girls at risk of criminality and eventually became an approved school. It closed in 1981 with the land redeveloped for housing. The fate of Meredith’s many charities is not clear.

Although there appears to be no collection of her papers, Mrs. Meredith exists in the archives. You can find her in Google, on archive.org, in newspaper collections, in scholarly books and listed in tomes reporting on conferences and charities. In south London, where she did most of her work, however, there is no trace.

Mrs Meredith is the subject of one of the chapters in Naomi Clifford’s book Out of the Shadows: Essays on 18th and 19th Century Women (Caret Press), available from Amazon or to order from bookshops

References

| ↑1 | HO144/11984/47. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Alexandra Magazine, whose aim was to reach a readership of women already working for a living, closed in 1856 after about a year of publication. See: Sheila Herstein (1993). The Langham Place Circle and Feminist Publications of the 1860s. Victorian Periodicals Review, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp.24-27. |

| ↑3 | In 1864, the social reformer Mary Carpenter’s book Our Convicts alerted the public to the appalling conditions for women prisoners at Brixton Prison. |

| ↑4 | E.C. Wines (1873). Report on the International Penitentiary Congress. Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 237-8. |

| ↑5 | p.8. |

| ↑6 | After the 1853 penal servitude act, only long-term transportation remained and that was abolished after the penal servitude act of 1857. A few convicts were transported after the 1857 act, with the final transportations taking place in 1868. |

| ↑7 | Russell House was at 2 Mitcham Lane. It closed in 1888 when the premises were taken over by a Roman Catholic mission to fallen women. |

| ↑8 | Evening Standard, 2 August 1879, p.2. |

| ↑9 | Nine Elms Station was originally a goods stop but had been renamed Queen’s Station or the Royal Station in 1854 when it was converted for the use of the Royal family. It was demolished in 1878. |

| ↑10 | Daily News, 25 July 1871, p.5. |

| ↑11 | Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, 19 April 1881, p.4. |

| ↑12 | W. G. Blaikie, The Princess Mary’s Village, Addlestone. The Sunday Magazine, 1875, p.420. |

| ↑13 | The National Archives; Kew, London, England; 1871 England Census; Class: RG10; Piece: 671; Folio: 73; Page: 17; GSU roll: 823327 |

| ↑14 | Sunday Magazine, op. cit. |

| ↑15 | The establishment was named after Princess Mary Adelaide, Duchess of Teck, who cut the first turf. |

| ↑16 | The Star, 27 April 1880, p.4. |

| ↑17 | The Daily News, op. cit. |

| ↑18 | The laundry had moved to Stockwell by this time, and the rest of the site redeveloped. |

| ↑19 | Banffshire Journal and General Advertiser, 31 December 1878, p.3. |

| ↑20 | The Wesleyan-Methodist Magazine (1883), Series 6, Vol. 7, pp.142-149. |

| ↑21 | Lucia Zedner (1991). Women, Crime, and Penal Responses: A Historical Account. Crime and Justice, Vol. 14, p.338. |

| ↑22 | Daily News, op. cit. |

| ↑23 | Published in 1881 by James Nisbet (London) |

| ↑24 | The Daily News, op.cit.; based on the advertised auction of lots when the laundry closed we can speculate that the move was prompted by a need to mechanise the laundry operation. |

| ↑25 | Evening Standard, 2 March 1883, p.7; Rugby Advertiser, 27 October 1880, p.2. In order to survive the venue offered diverse entertainments including music concerts and bicycle races which led to problems with the licensing authorities. |

| ↑26 | Anne Beale, Prison Missions, Newbery House Magazine (1891), Vol. 4, pp.718-724. |

| ↑27 | South London Chronicle, 1 August 1885, p.4. |

| ↑28 | Patricia Barrass (1950). Fifty Years in Midwifery: The Story of Annie McCall, M.D. London: Health for All Publishing Co, pp.37-41. |

| ↑29 | Dr McCall moved the outpatients department to her own home a few doors away at 131 Clapham Road. It subsequently moved to Fentiman Road (exact location unknown), then to McCall’s new address at 161 Clapham Road, and eventually to Jeffreys Road, the location of the Annie McCall Hospital. |

| ↑30 | Morning Post, 18 June 1900, p.6. |

| ↑31 | Morning Post, 20 December 1901, p.5. |