In their day, two centuries ago, Vauxhall Gardens’ waiters were variously described as insolent swindling rascals, or as the epitome of unobtrusive efficiency. But who were they really, and what were their working conditions? asks David Coke, co-author of Vauxhall Gardens: A History.

Because of the lack of obvious documentation, modern historians have largely ignored them as well as their central role in Vauxhall’s profitability. In fact they were pivotal to the early and continuing success of Jonathan Tyers’s pleasure garden, and he is known to have valued them highly, even though he never actually employed them, leaving them to make an income as best they could. Some thrived in this atmosphere, but others fell by the wayside.

The Morning Chronicle newspaper of Monday 24 June 1822 carried on the back page, under ‘Situations Wanted’, a small advertisement:

As Waiter, in Town or Country, a Single Young Man that thoroughly understands his business, and can command a five years character from his last situation. A line addressed to J.B., post paid, to No.38, James-street, Lambeth-marsh, will be duly attended to.”

This unassuming notice takes us into the private life of an ordinary inhabitant of Lambeth two centuries ago. There is no obvious reason to assume that ‘J.B.’ was a Vauxhall waiter, but the circumstantial evidence is compelling. First, he lived within easy walking distance of Vauxhall Gardens, as most Vauxhall waiters would have done; James Street was a terrace of small houses in Walworth, close to where Browning Street is today. Second, Vauxhall Gardens provided employment for a large number of waiters in an area where few others would have been required. And third, Vauxhall Gardens had changed hands the year before, so staffing changes and reorganisations would not have been unexpected. A minor supporting detail in the notice is that the ‘single young man’ calls waitering his ‘business’; the waiters at Vauxhall were all self-employed, so it would indeed have been his business, rather than his trade.

Vauxhall’s waiters were a vital and integral part of the establishment. Without their efficient, seamless, and inconspicuous work, Vauxhall Gardens could not have succeeded. It is clear that Jonathan Tyers, Vauxhall’s great entrepreneur, valued his waiters, in some cases above his performers. It was through the refreshments served by the waiters that Tyers made most of his income. The infamous ‘Reinhold Affair’, during which Tyers angrily defended his waiter, Mr Tilt, against the accusations of his bass singer, Mr Reinhold, shows clearly where Tyers’s priorities lay.[1]See D. Coke: ‘Vauxhall in an Uproar’, in The London Journal, vol. 41 no.1, March 2016, 17-35. There is good reason to believe that Tyers’s waiters were well trained in their job, and were highly valued by the proprietors, but it is also clear that any diversion from, or delay to, their work would have been harshly punished, probably with summary dismissal. Indeed, during the opening Ridotto al Fresco of 7 June 1732, the story is told that ‘A Waiter belonging to the House having got drunk, put on a Dress, and went to Fresco with the rest of the Company; but being discovered, he was immediately turned out of doors.'[2]Daily Advertiser, 21 June, 1732.This picturesque incident was recalled in the humorous Vauxhall Papers of July 1841,[3]p.36. so had probably become one of the legendary stories handed down through generations of waiters.

The more usual strict order with which the gardens were run is mentioned by John Lockman at the end of his 1751 guidebook to the gardens.

After the Sketch thus attempted of these Gardens, it may not be improper just to hint at one Circumstance, that contributes very much to the Convenience, as well as to the Beauty, of this Entertainment; and for want whereof, indeed, it could not well subsist: I mean the Readiness with which the numberless Tables are serv’d, with whatever may be call’d for; a Decorum that could not take Place, nor the Master of the Gardens keep a just Account of the various Articles deliver’d out to his Waiters, was it not for Order. This, indeed, is so exact, that Many have wonder’d how it could be possible for three or four thousand Persons to be regularly entertain’d, at different Tables, at one and the same Time.”[4]John Lockman, A Sketch of the Spring-Gardens, Vaux-Hall, in a letter to a Noble Lord. London: G. Woodfall, 1751, p.24.

Lockman, who was Vauxhall’s publicist, is normally a reliable source of information, so although his assertion that ‘three or four thousand Persons’ ordered food and wine on a regular basis may appear to be an exaggeration, the ‘five hundred separate suppers’ mentioned independently by a journalist in 1739 [The Scots Magazine I, Sept 1739, p.409] could represent the number of tables served, and with each table seating six or eight people, we come to a similar total. With such numbers, Vauxhall’s kitchens and waiters would have been at full stretch on many occasions. One such was seen in 1781, when it had been announced that the Duke and Duchess of Cumberland would be attending a Sailing gala at Vauxhall; it is said this attracted some eleven thousand visitors, of whom seven thousand ordered refreshments. Even if both figures are exaggerated, it must have been an occasion such as this to which one historian referred when he reported a story told him by an elderly retired waiter. At one o’clock in the morning, the cook of the Gardens apparently rushed up to this waiter and implored his assistance. He must send someone up to the market to buy fowls and other food, because of the enormous demand. On a similar evening (or early morning) the cook asked him to come and help in the kitchen, because orders for four hundred roast chickens had just come in. [5]H.H. Montgomery, The History of Kennington and its Neighbourhood, London, 1889, p.87.. We can only hope that the loyalty and hard work of these men was duly rewarded.

Vauxhall’s waiters had to make their own income – they were not paid a salary for their work. There were various ways they could do this – first from gratuities given by their customers. This was not always a reliable source of income, but some visitors could be very generous, especially if they had received good service. It is well documented that, on heavily-attended special occasions, waiters could earn substantial tips by finding seating or refreshements for a wealthy party who found themselves crowded out by the mob. During the 10 May 1769 Ridotto al Fresco, when around ten thousand visitors are known (from the ticket numbering) to have attended, one waiter boasted of having earned six guineas more than usual (almost £600 today).[6]Winston Collection, Bodleian Library, I, item 139.2.

Other possible sources of income were provided by Tyers himself, who would have offered his waiters other employments at the gardens; some waiters were certainly also lamp-lighters, and some would have worked in the Vauxhall kitchens, or even as gardeners or handymen. Tyers knew the value of loyalty in his staff, as well as the importance of staff morale. This is demonstrated clearly in an episode of 1739, when two of Tyers’s waiters wanted to marry two of his barmaids. Tyers not only gave each couple a ring, but also a slap-up dinner at his country house near Dorking, to which fifty of his other employees were invited. This event shows something about the numbers of staff employed at Vauxhall. The fifty invited to the wedding feast must have been less than half of the establishment, because Vauxhall Gardens did not close that evening – it would have been fully operative and well-staffed despite fifty of them being absent.

Even though women served behind the bar [see fig.1], the waiters at Vauxhall, like the musicians, were all male, and there is no evidence to suggest that they were anything other than white and British. In some, probably rare, cases, good-looking waiters could play their part in the fantasies of visitors. One such scenario is related in 1737, when the promiscuous wife of a ‘Courteous Knight’, had been deprived for the evening of her usual lover, one of her husband’s footmen:

But barr’d from thence she turns her View,

On the smug Waiter, with his Apron blue;

The painted Tin upon his rising Crest,

Pleases her Sight, and warms her am’rous Breast.

Not the blue Ribbon, with fam’d Edward’s Star,

Can with this Tapster’s Clout and Badge compare,

At Home, perhaps, with more than common Joy,

She’ll hug her Knight, whilst dreaming of this Toy.

He to reward her Love, and keep it still,

Next Morn presents some Jewel or some Bill,

This sold or chang’d, Eftsoons a Part is sent

To Tom, who guess’d last Night, at what she meant.

An Assignation’s made by trusty Nancy,

Unless some other Slave first strikes her Fancy.[7]Anon: A Trip to Vaux-Hall: Or, A General Satyr on the Times. With some explanatory notes. By Hercules Mac-Sturdy, of the County of Tiperary, Esq. London, Printed for A. Moore, 1738. British Library, … Continue reading

The ribbon and star refer to the regalia of Knights of the Bath, whose charms the Lady rejects in favour of her ‘toy’, a uniformed waiter or footman, or some other servant.

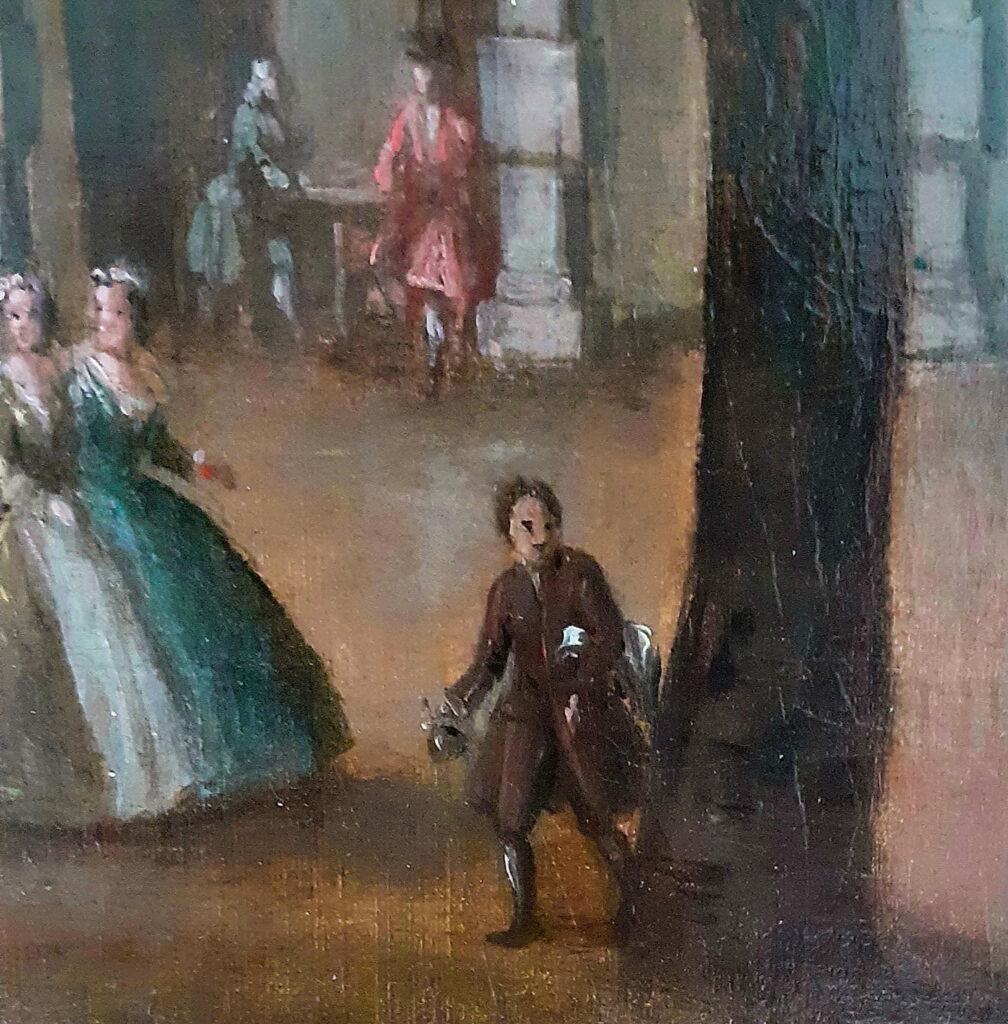

The waiters, in the early days, were distinguished by their costume. They wore a frocked overall (the ‘Tapster’s Clout’), in a blue or brown fabric, over which they wore a blue apron [see Fig. 2]. In Tyers’s time, each waiter also wore a numbered enamel badge (the ‘painted tin’ mentioned above, a little like old French house-numbers), and the corresponding number would be attached to one of the dining tables [see Fig. 3]. According to an article in the Scots Magazine of 1739, each waiter had ‘a certain number of tables committed to his charge’.[8]The Scots Magazine I, Sept 1739, pp.409-410 The speed with which five hundred suppers could be dispensed suggests that each waiter was assigned just two or three tables; if two, it would mean that there would have to be at least fifty waiters employed, to look after the five dozen supper-boxes, and the three dozen tables in the Grove. It is unlikely that all the tables were occupied every evening, and some evenings would have been busier than others, so giving considerable latitude in the numbers of staff required.

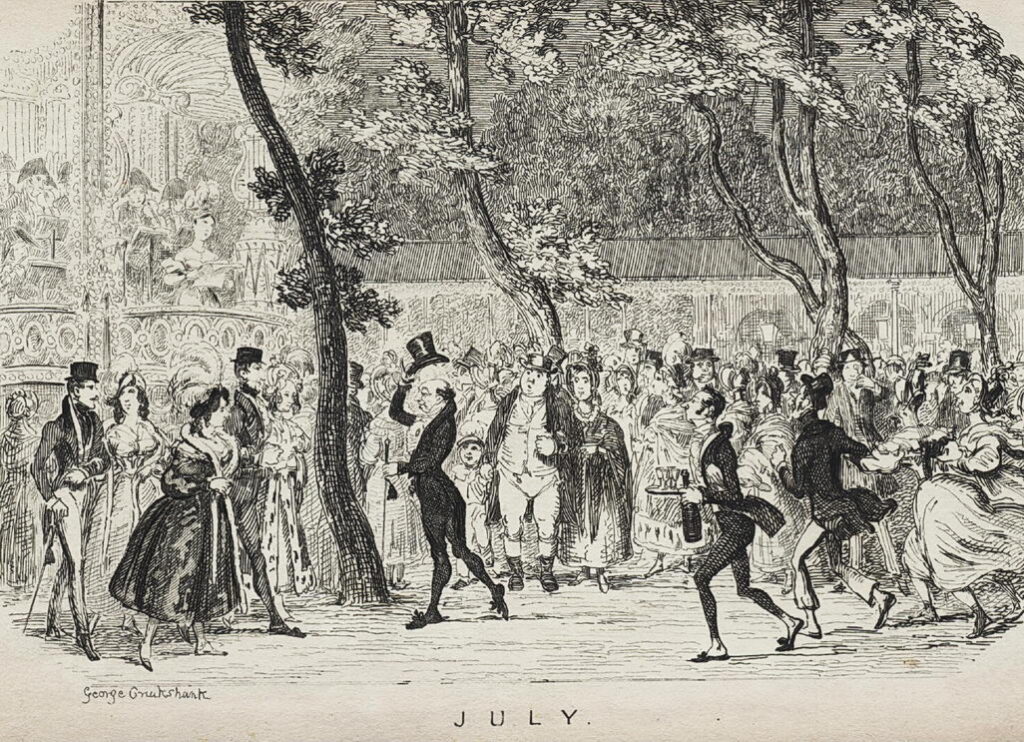

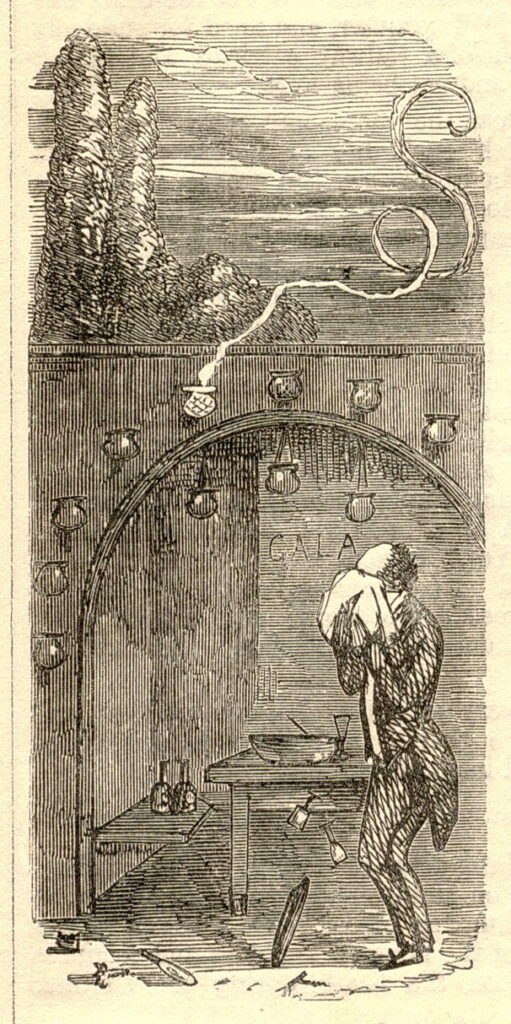

This was no doubt one reason why Tyers’s waiters had to be self-employed – they took all the risk of having no customers. They also took the even greater risk of their customers avoiding payment or just refusing to pay (a practice called ‘bilking’ the waiters, a favourite ‘sport’ among the so-called ‘smarts’) – waiters had themselves to pay for all refreshments at the bar before selling them on to their customers. This system would have led to rivalries and hierarchies among the waiters themselves, meaning that the best and most loyal waiters would always have obtained the first and best customers, giving all waiters the positive incentive to do the best they possibly could at their jobs, or to use other methods, like bullying, to have their own way. ‘J.B.’ in the advertisement above may not have been made redundant, he may just have become fed up with the system at Vauxhall, and the seasonal and vulnerable nature of the work. The fact of their self-employment is highlighted in a satirical piece about Vauxhall and Ranelagh published in 1742. Waiters at the time were called ‘drawers’ because their most obvious public role was in drawing the corks out of bottles (see Fig. 4); the satire is written in imitation of Biblical verses. The narrator had crossed the river and entered the Vauxhall Grove:

35. Then I beheld a Drawer, and he looked wistfully upon me, and his Countenance said, Sit down.

36. So I sate down; and I said, Go now, fetch me savoury Meats, such as my Soul loveth; and he straitway went to fetch them.

37. And I said unto him, Asked I not for Beef? wherefore then didst thou bring me Parsley?

38. Run now quickly and bring me Wine, that I may drink, and my heart may chear me, for as to what Beef thou broughtest me, I wot not what is become of it.

39. Now the Wine was an Abomination unto me; nevertheless I drank, for I said, “Lest peradventure I shou’d faint by the Way”.

40. And I said, Tell me now what is to pay: and He said, Thou shalt know what is to pay.

41. Then pulled I out three Pieces of Silver, and I gave them unto Him, albeit He looked displeased at me, as who shou’d say, Pay me that thou owest me.

42. Have I not been thy Slave and thine Ass these five Minutes? Have I not served thee faithfully? according to the Thing thou gavest me to do, even so did I.

43. Moreover have I any Wages save what thou givest me? Wherefore then dost Thou with-hold from me that which is my due, and givest me not Six-pence? So I gave him Six-pence.

44. But after this He neither bowed, nor made any Obeisance unto me, and I repented of what I had done.[9]The Evening Lessons. Being the First and Second Chapters Of the Book of Entertainments. Woe unto thee, Ranelagh! Woe unto thee, Vaux-hall! Woe unto thee, O Cuper’s! And Woe! Woe! Woe! to the … Continue reading

The reference to ‘parsley’ is a comment on the infamous thinness of the slices of meat produced at the Gardens. Vauxhall’s wines too had a low reputation. The poor quality, mean quantities and high cost of all the refreshments soon became an ‘in-joke’ among Vauxhall’s regular visitors, who enjoyed watching the horrified faces of first-time visitors when they were given their food and when they later received their bill. Sixpence would have been a generous tip, amounting to around 20 per cent of an average bill. Even at this early date, the ‘drawers’ were seen as insolent and ungrateful, in common with many of their peers in domestic service.

By the 1740s, waiters were wearing costume that was closer to everyday dress of coat and breeches, but the coat would normally be buttoned up to the neck, and the suit would be all of one dark colour. The waiters never wore or carried hats [see Fig. 5]. A few years later, the waiters’ costume became even more like their customers’, except, of course, of lesser quality. The only way of differentiating between waiters and visitors in prints of the 1750s onwards is that a waiter will normally be carrying a tray or a bottle, with a napkin over his arm, and will always be in a hurry. By the time Vauxhall closed in 1859, there is evidence that the waiters were wearing red coats, to mark themselves out from visitors. Although this detail is not seen in the visual documentation, a valediction to Vauxhall published in the Sydney Morning Herald on 17 August 1859 talks of what will be missed (and what will not) once Vauxhall has closed, and makes mention of all the waiters’ red coats that will be found in London’s second-hand clothing markets.

The one certain thing about Vauxhall’s waiters is that they were an accepted and essential part of the setting. Waiters turn up with great regularity in the visual documentation of Vauxhall throughout its history, from the 1736 Vauxhall Fan in which a waiter on the left is stooping to pick up a dropped cold chicken, all the way through to the 1859 photograph of the Orchestra. The few images included with this article are by no means the only views of Vauxhall showing waiters; indeed, a pleasant few hours can be passed playing ‘spot-the-waiter’ when looking at such pictures. They often appear close to a tree or other fixed landmark, so as to mark them out as belonging to the establishment, but they are sometimes in a prominent foreground position, with a specific role to play (see Fig. 6).

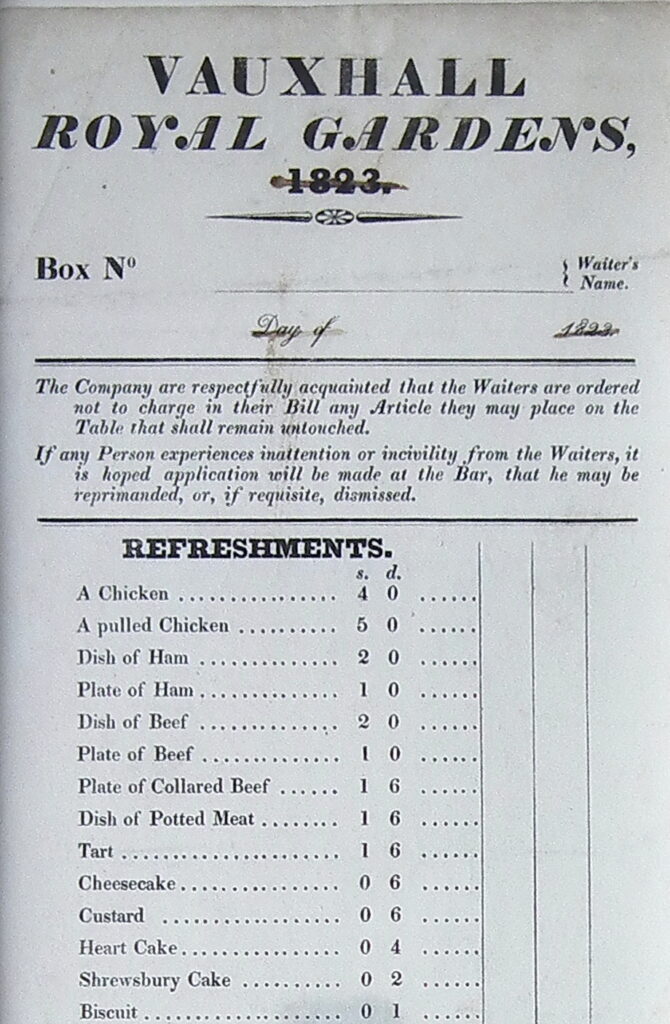

Vauxhall’s waiters also make themselves felt in the printed ephemera; bills of fare often include warnings to visitors not to accept from their waiter any wine that comes to the table without its proper seal, nor to pay for any plates of food that have not been touched (see Fig. 7). Visitors are also asked to report any inattention or incivility from a waiter, so ‘that he may be reprimanded, or, if requisite, dismissed.’ A notice of the 1820s, after the Gardens had passed into new management, baldly states ‘Visitors are earnestly requested not to pay for any kind of Refreshment without being furnished with a Printed List, with the Prices attached. In case of any Imposition being attempted by the Waiters, Visitors will confer a favor on the Proprietors by making a COMPLAINT AT THE BAR.'[10]Lambeth Archives, Minet Coll. IV 162/13/2, and IV/162/12. Notices like this must have been posted up where visitors could see them, but the impression given is that the real audience was the waiters themselves. These notices, which are contemporary with the advertisement at the start of this essay, make it clear that waiters had worked out some less honest ways to make their work pay, and that they could not be trusted not to cheat their customers. In any case, the onus was on the customers themselves to detect and report such behaviour, the Proprietors state that they ‘cannot answer for the conduct of the Waiters’, presumably because they were still self-employed.

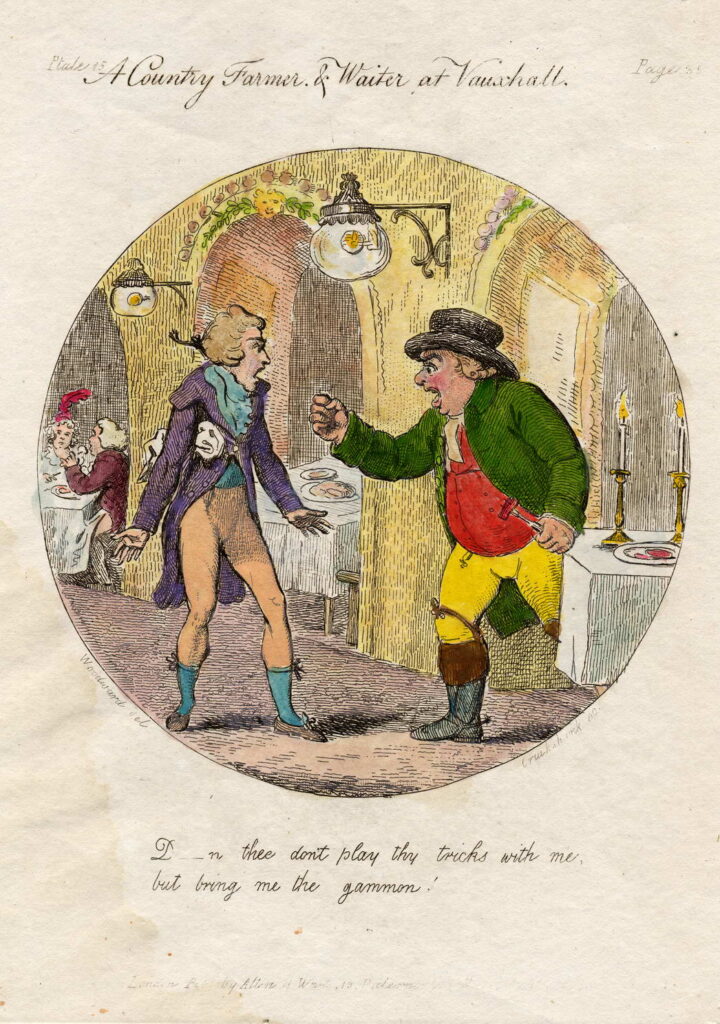

Every now and again, waiters appeared in written satires on Vauxhall, giving a closer insight into their work and their dealings with the public. An outstanding example of this dates from the last years of the 18th century, and concerns the first visit to Vauxhall of a farmer on his own (see Fig. 8). It is worth quoting at length as a vivid picture of the Gardens at the time. Upon entry to the Gardens, the farmer is at first dazzled by the amazing display of multi-coloured lamps, however:

After hearing the various songs, staring at the lamps, crowding to view the waterfall, and enjoying the rest of the amusements, his ears were saluted by sounds much more congenial to his home-spun notions, than the empty display of gorgeous machinery; in short, the hurry of the waiters, rattling of plates, and smoothing of table-cloths, informed him that something substantial was going forward. After a few moments reflection he resolved as he had begun, to go through with the whole, and once in his life, do the genteel thing: he accordingly seated himself in a box, and called for the waiter. Being always possessed of a communicative and open disposition, it is not surprizing that in a few minutes he found out the man’s name was Richard, and that he had been in the capacity of a waiter about a twelvemonth, that he was unmarried, and such like important intelligence, for which in return he politely favoured Dicky (for so he familiarly called him) with the outlines of his own history; where he was born, at what place he lived, and that he was resolved for once by the way, to spend a little money as well as his neighbours, hoping that Dicky would not forget to call and take a pipe and taste his tap, if he should chance to travel through his country, assuring him it would be worth his while, and that he should have a hearty welcome! After many eulogiums on his wife Molly’s brewing, he concluded by enquiring what there was in the house for supper?

Two large wax candles being placed on the table, the bill of fare was produced; after casting his eye over several articles and smacking his lips, as he spelt the words in rotation, he fixed on ham and fowl, because he said “it put him in mind of whoame; for though he said it that should not say it, Molly had as pretty a method of cutting up a pig, and fattening poultry, as any Duchess in the land, let her be who she would; – and d’ye hear Dicky, bring in some home-brew’d – none of thy London tricks for me – I’ve seen the world lad, so bustle about mun, and let’s have some’at to begin with, for by th’dickens I’m almost famish’d!”

After waiting a considerable time supper was brought in – the fowl met with some degree of approbation, but the ham changed his countenance to muscular expressions of the greatest surprise and astonishment ! He called loudly for his friend the waiter (whom he now believed to be little better than a rogue) and holding up a slice on the end of his fork, he vehemently exclaimed, “What the devil dost thee call this ? – why I could eat zeven such little parings at a mouthful – D—n thee don’t play thy tricks with me, but bring me the GAMMON!” [See Fig.8] – “The gammon your honour!” replied the waiter, “I don’t rightly understand you, but I’ll go and enquire at the bar.” On saying this he slipped out, glad of an opportunity of making his escape, for the enraged countenance, and doubled fist of the farmer, began to wear a formidable appearance. – After giving him a little time to compose himself, the man returned with the utmost diffidence, “assured his honor, that his master would be happy to accommodate him, but that such requests were foreign to the rules of the gardens.” – “Rules ! don’t tell me of rules ! I fancy thee and thy master make it a rule to starve people, and pick their pockets at the same time; and let me tell thee, such doings is a burning sin, and a sheame, and thee’ll both have to answer for it.” – “I’m sure that is not our intention your honour, would your honour chuse any thing else ?”

So many honours began to soften our country hero into a tolerable good humour; and to make some amends for the loss of the gammon he ordered an additional fowl, with a few tarts and cheesecakes, and at the same time a bottle of the best old port, a pipe, a paper of tobacco, and a lanthorn. – The refusal of the latter articles, on account of smoaking not being allowed, had nearly occasioned a fresh gust of passion, but on being clearly convinced that it was not genteel, he reconciled himself to his fate. After enjoying himself about an hour and a half (by which time he had completely finished his bottle) he deemed it necessary to know what he had to pay. When the bill appeared the different items were truly alarming ! but what seemed most to command attention was three shillings for wax lights ! This last charge produced the following elegant address to the waiter: “Thou Rascal! if thee coms’t into our country I’ll have thee hang’d, – don’t think I’m in a passion ! – but mind what I say. – I don’t care for thy long bill half a farthing, because why ? I’ve got money in my pocket to pay for it (more than thee hast I’ll be bound); yet at the same time I canna but say that it hurts me sorely to pay three shillings for these two farding candles ! – but however thee shalt get nothing by it, so bring me in another bottle, for here I’ll sit till they are burnt down to their sockets ! and if ever thee catchest me doing the genteel thing again, may I never more see my wife Molly, nor enjoy the comforts of my own whoam !” He kept strictly to his word in every particular, and curses FOX HALL ! in his chimney corner to the present hour.[11]George Moutard Woodward, Eccentric Excursions or, Literary & Pictorial Sketches of Countenance, Character & Country in different parts of England and South Wales. London: Allen & West, … Continue reading

This piece, with its accompanying illustration (see Fig. 8), is the epitome of the Vauxhall ‘in-joke’ about the refreshments. Reading the text it is easy to imagine the inhabitants of the neighbouring boxes (visible in the background) indulging in a fit of humour at the farmer’s expense.

Vauxhall Gardens is often referred to by historians as ‘theatrical’. If this is so, then the waiters were an invariable and essential member of the cast, alongside the musicians and their audience (see Fig. 9). Some indeed, as in modern times, may have been out-of-work actors themselves. Tragically, we know very little about either the working conditions or the private lives of Vauxhall’s waiters. Information tends only to surface if they appear in the police courts, which was rare, or if some tragedy occurred. Joseph Trippet, Vauxhall waiter, was indicted at the Old Bailey for theft on 14 June 1769, with his partner in crime and colleague James Fannen; in his evidence statement, Joseph himself tells us that his work normally finished by 1 or 2 o’clock in the morning.[12]Proceedings of the Old Bailey, Ref: t17690628-30]. Trippet called as character witnesses Stephen Paxton and William Morris, who may have been work colleagues. Two decades later, one of Trippet’s successors, a Mr Gahey, lost his life when he was attending the starting cannon for a Vauxhall sailing match in June 1791; the cannon, inexpertly loaded, blew up, killing Gahey in a particularly gruesome manner. And James Scrufus, who might have worked with Gahey, had faced a paternity suit three years earlier. Other named waiters include John Asquith, who also worked at Bagnigge Wells in the 1780s, William Everit, who lived in the parish of St George’s in Southwark, Joseph Harrison, employed at Vauxhall in 1785, a prospective waiter called John Wharton, who was accused (and acquitted) of stealing £20 from a visitor in 1823 (whether he was then employed as a waiter we do not know), and Benjamin Jessup, the Principal Waiter in 1823.

With one precious exception, no details about the lives of any of these men have come down to us today. That exception was Robert Wilson; Robert was born on 9 August 1747 in March, Cambridgeshire. He grew up in a farming family, trained in agriculture by his father Thomas. Aged 28, however, Robert decided one day that he needed to broaden his horizons, and he left the farm, taking his father’s favourite mare, to travel to London and beyond. He must have arrived in London at around Christmas-time 1775, when he took up a job, presumably menial, in a Lambeth glass factory. That winter of 1775-6 was one of the coldest on record, with severe frosts, snow, storms and fog; the sub-zero temperatures through January would have vindicated Robert’s choice of work-place, where the furnaces would have kept him warm. However, by the end of May, the glass-house job had lost some of its allure, so ‘I then engaged as a waiter at Vauxhall-gardens, and staid there ten weeks. The latter situation being temporary, I entered my name at two register-offices, by which means I got a place as footman at a French boarding-school at Upper-Clapton.’ Robert was clearly not one to stick fast, and indeed, he went on to become the ‘Well-known Pedestrian’ and traveller who wrote of his ‘Remarkable Adventures, his Extraordinary Sufferings, and Wonderful Escapes, during a peregrination over a considerable portion of the Globe’ in a memoir of 1807. The memoir even includes a full-length portrait of the author.

Robert’s stay at Vauxhall Gardens was always going to be short-lived, but ten weeks was probably not even the whole of the 1776 season. It is frustrating that Robert tells us nothing of his employment, but we can at least deduce that a young countryman arriving in London for the first time was able to persuade the proprietors to employ him, even on a temporary basis, and that such men coming and going was probably a normal feature of Vauxhall’s daily life. It also shows that an ambitious Vauxhall waiter could move on to a superior post if he wanted to. But Robert’s ambition drove him eventually to board ship for the West Indies and North America, where his adventures truly started. He did not return home for more than six years, to find his father had recently died, and that it was now his job to maintain the family farm ‘with Christian fortitude and resignation.’

Whether J.B., in the advertisement at the beginning of this article, had left his job willingly, like Robert Wilson, or was let go by the proprietors, is not known, but a skilled and experienced waiter, especially a well-trained Vauxhall waiter of five years’ experience, would have been in high demand from the burgeoning hospitality industry in London at that time. We can rest assured that he would not have been unemployed for long. Like Robert Wilson, and many others of his colleagues, he may even have achieved some promotion and improved working conditions through a new position.

David Coke, October 2020.

References

| ↑1 | See D. Coke: ‘Vauxhall in an Uproar’, in The London Journal, vol. 41 no.1, March 2016, 17-35. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Daily Advertiser, 21 June, 1732. |

| ↑3 | p.36. |

| ↑4 | John Lockman, A Sketch of the Spring-Gardens, Vaux-Hall, in a letter to a Noble Lord. London: G. Woodfall, 1751, p.24. |

| ↑5 | H.H. Montgomery, The History of Kennington and its Neighbourhood, London, 1889, p.87. |

| ↑6 | Winston Collection, Bodleian Library, I, item 139.2. |

| ↑7 | Anon: A Trip to Vaux-Hall: Or, A General Satyr on the Times. With some explanatory notes. By Hercules Mac-Sturdy, of the County of Tiperary, Esq. London, Printed for A. Moore, 1738. British Library, 840.m.5. |

| ↑8 | The Scots Magazine I, Sept 1739, pp.409-410 |

| ↑9 | The Evening Lessons. Being the First and Second Chapters Of the Book of Entertainments. Woe unto thee, Ranelagh! Woe unto thee, Vaux-hall! Woe unto thee, O Cuper’s! And Woe! Woe! Woe! to the Frequenters thereof!. London, Printed for W. Webb near St. Paul’s. 1742. (included in the Jacob Henry Burn volume, British Library Cup.410.K7, at f.139-150). |

| ↑10 | Lambeth Archives, Minet Coll. IV 162/13/2, and IV/162/12. |

| ↑11 | George Moutard Woodward, Eccentric Excursions or, Literary & Pictorial Sketches of Countenance, Character & Country in different parts of England and South Wales. London: Allen & West, 1796-7. With engravings after Woodward by Cruikshank. pp.34-7. |

| ↑12 | Proceedings of the Old Bailey, Ref: t17690628-30]. |