by David E. Coke

The patrons of the Royal Gardens, Vauxhall, will regret to learn that a Gentleman (Mr Simpson) whose name and person have for so many years been associated with that popular scene of recreation, is no more. The well-known ‘Master of Ceremonies,’ who has filled that distinguished post for 38 years, to the infinite advantage of the Proprietors, and gratification of the public, departed this life on Friday, the 25th ult.” —The Examiner, no.1457, Sunday 3 January 1836, p.13. Coke Vauxhall Collection CVC 0656.

This is one of many published notices of the death of one of Vauxhall’s great historic characters. C.H. Simpson, as he was universally known, was born Christopher Herbert Simpson, the fourth son of George and Dorothy; he was baptised, like his three elder brothers and younger sister, in the parish of St George, Bloomsbury. A shorter obituary appeared in the prestigious Gentleman’s Magazine’s ‘Deaths’ column. ‘25 December 1835. Mr. C.H. Simpson, late Master of the Ceremonies of the Royal Gardens, Vauxhall; so long the butt of the newspaper wits, and well-known from his grotesque whole-length portrait. He had served in the Royal Navy.’[1]Volume V. (ns) Feb. 1836, p.210.

As Master of Ceremonies at Vauxhall, Simpson was widely known and recognised by the character he assumed. Exquisitely dressed in old-fashioned costume, his obsequious civility to everybody, whoever they were, and whatever they had done, became proverbial. His deep bow of welcome ‘to the Royal Property’ (i.e. Vauxhall Gardens), exercised after a polite step back to allow space for the elegant sweep of his arm, was indiscriminately received by anybody standing close enough. We are assured that Simpson was ‘endowed with ubiquity’, as he appeared to be everywhere in the gardens at once. ‘He has attended here . . . every public night from eight at night until three in the morning for above twenty years!’ Whenever there was any sort of disturbance, ‘He pierces through the mob like an eel in mud’ to calm things down.[2]William Clarke, Every Night Book, or, Life After Dark. London: T. Richardson, 1827, p.187.

Simpson’s panache and civility did have a practical application; a news report of 1833, reports a disturbance at Vauxhall, caused by ‘a party of “peep-a-day boys”’ (hooligans) who had been drinking heavily. One of them was a big, powerful youth, who discouraged any attempts by waiters or others to get in his way. The call went out for Simpson, who came out and made a most profound bow to the riotous swain, who, on seeing Simpson’s hat flourishing in the air, his fine oval powdered cranium bare, cried out, with a thundering voice “who the h—l are you?” – the M.C. bowing to the ground, answered with the greatest complacency “Your very obedient humble servant” – “You be d—d.’; Simpson: “Sir, you do me honour.” Buck: “Honour, the d—l.” Simpson: “Sir, you are perfectly right, he ought to be honour’d.” Buck: “Who ought to be honour’d and be d—d to you.” Simpson: “Your own noble and generous self, who are the most good naturest gentleman I know.” Buck: “What do you know of me, you puppy.” Simpson: “Every thing that is valiant, courageous and manly.” Another profound bow, hat off, which the ungracious youth kicked into the air; but the peace-making philosopher, quickly picked it up – replaced it on his head, with that elegance of gait and manner so peculiar to himself, that it made even the rebel to smile, of which the M.C. taking advantage, addressed him thus, “Sir, you are little aware that I have the honour to know your noble relatives; his lordship, your extinguished father, is a great patron of the Royal Property; on that account, permit me, right honourable sir, to conduct you to your carriage: clear the way there, lamplighters and waiters, don’t commode his honour; this way, highly respected sir, this way.” – The youth tickled with the high rank the witty M.C. had bestowed on him, suffered himself to be led out of the Gardens like a lamb.[3] Lambeth Archives, Vauxhall Gardens Albums V, f.226. This was not the behaviour of an innocent or an idiot, but of a highly-practised diplomat and serviceman, well used to keeping order without aggression or violence – an ability of great skill.

By his own account, and confirmed by the historical record, Simpson had indeed served in the Navy as a boy. Between 1781/2 and 1783, he served as a young midshipman on board the new ship the 74-gunWarrior under its commander Capt. Sir James Wallace, a friend of his father’s. In this situation he saw combat, under Admiral Rodney, on 12 April 1782 at the ‘bloody and furious battle’ of Saintes in the West Indies, when the French fleet was soundly defeated and their admiral, the Count de Grasse, was captured. On 12 July he is marked as discharged, but the ship’s cash book shows he received his full wages of ₤61. 19s 10d, paid on 21 July; he returned to England, after more naval service, in 1783.

His naval career is reported in his address to the public on the occasion of his great benefit night at Vauxhall in 1833 (the printed address was on sale at sixpence per copy), but what the young C.H. Simpson did for the years between 1783 and 1797 is one of the mysteries that surround him. Vauxhall had strong connections with the London theatres, sharing several performers in common, and there were, at the time, several actors in London called Simpson, one of them even with the same distinctive pair of initials; C.H. Simpson the actor performed at the Adelphi Theatre in London between 1809 and 1820, but there is also a mention in 1787 of a Mr Simpson playing a valet in a pantomime called ‘Hobson’s Choice’ at the Royalty Theatre in Well Street (just to the east of the Tower of London). This may have been the better-known actor George Simpson, who died in 1795, but it seems an unusually minor role for such a figure at that time. Another record of an actor called Simpson places him at the Theatre Royal Brighton before 1809, where he was playing dashing young men or soldiers. Who is to say today but that a young character actor may have seen in the comic portrayal of the valet the embryo of a much more important role, even down to the costume?

It is entirely conceivable, although impossible now to prove, that Christopher Simpson, a competent jobbing actor may have decided to give up the allure of many insecure roles on the late Georgian stage for the security of the starring role at Vauxhall Gardens. To suggest that ‘C.H. Simpson, Master of Ceremonies at the Royal Gardens, Vauxhall’ was a role that Simpson chose to act is by no means to denigrate his achievements. His was one of the great comic theatrical roles of the 19th century, known and loved by a huge number of people, and equal to anything invented by Vesta Tilley or Dan Leno in the Music Halls, by Kenneth Williams in the ‘Carry On’ films, or indeed among the television soap stars of more recent times.

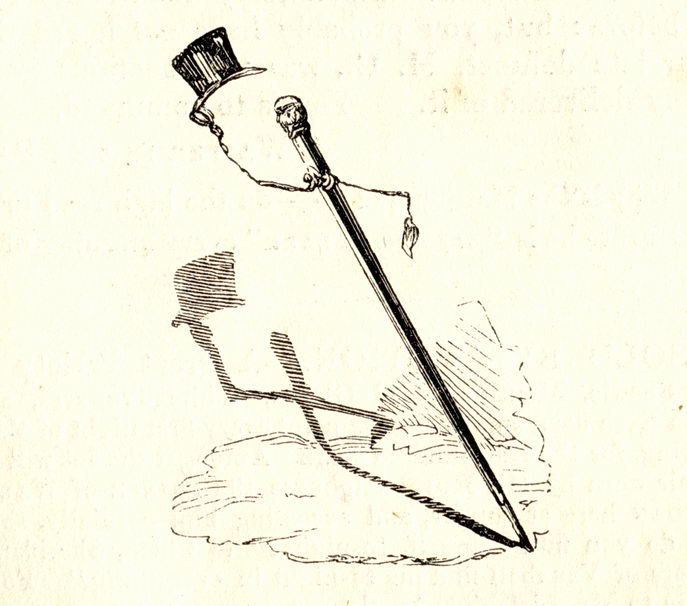

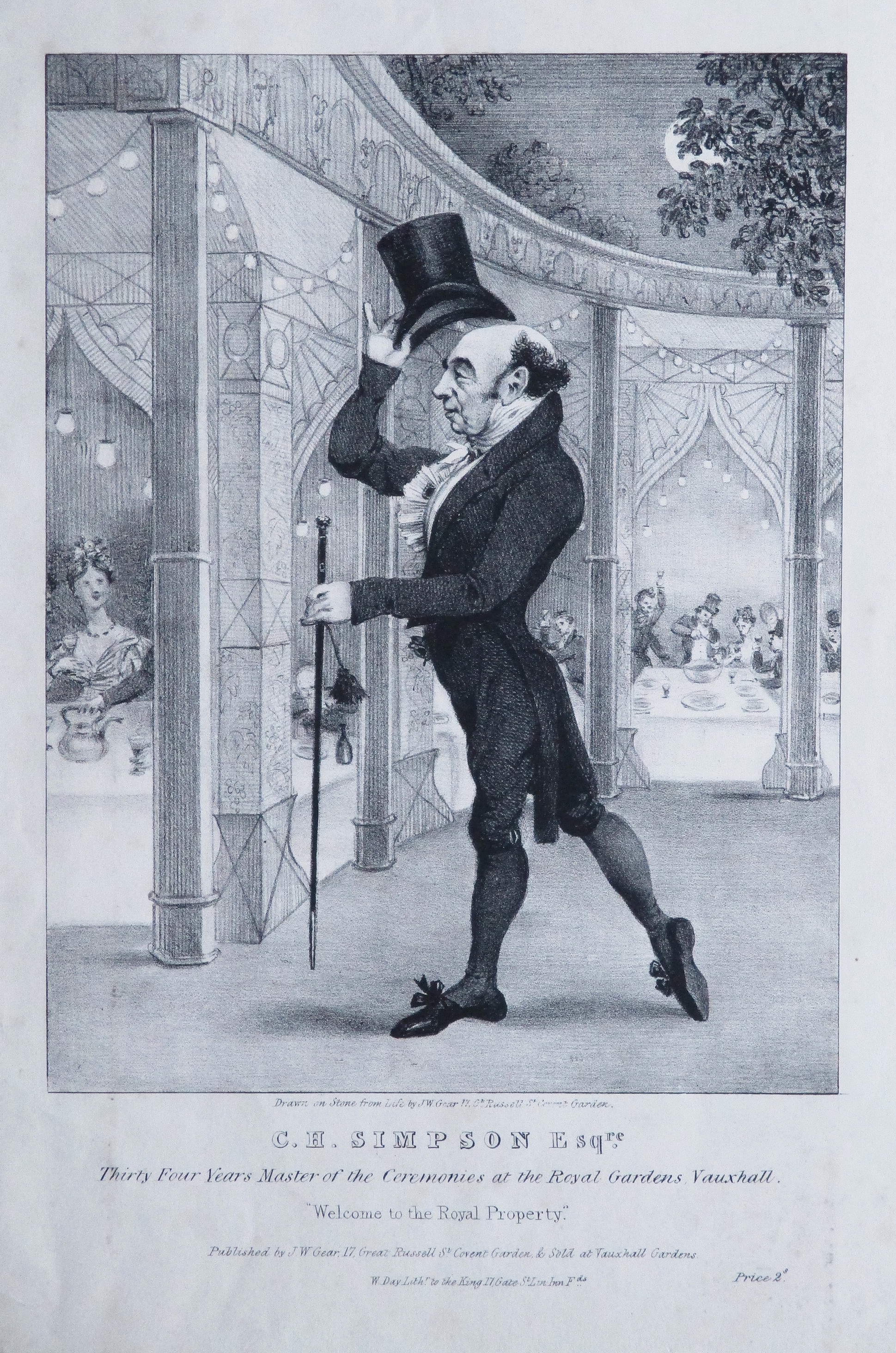

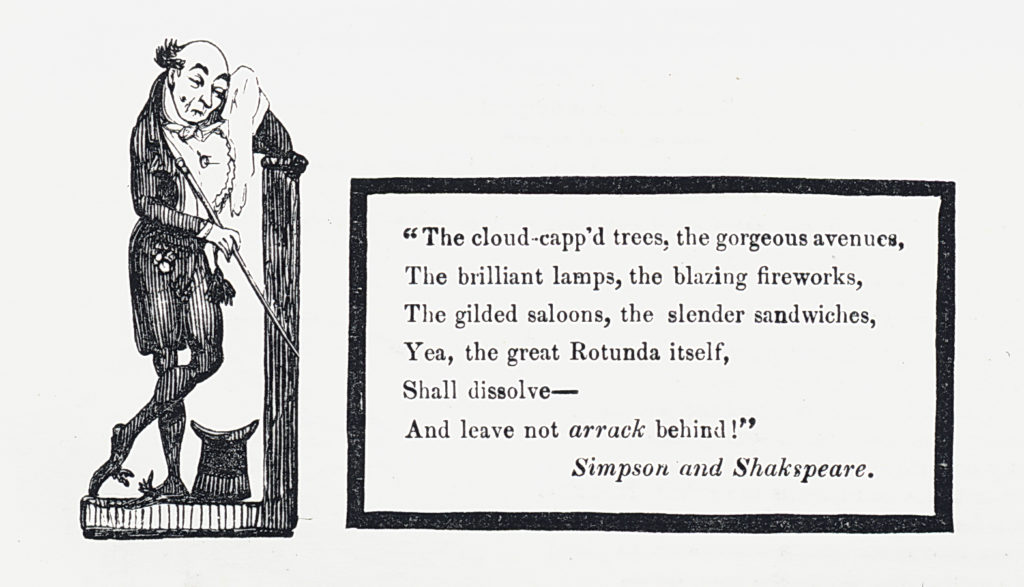

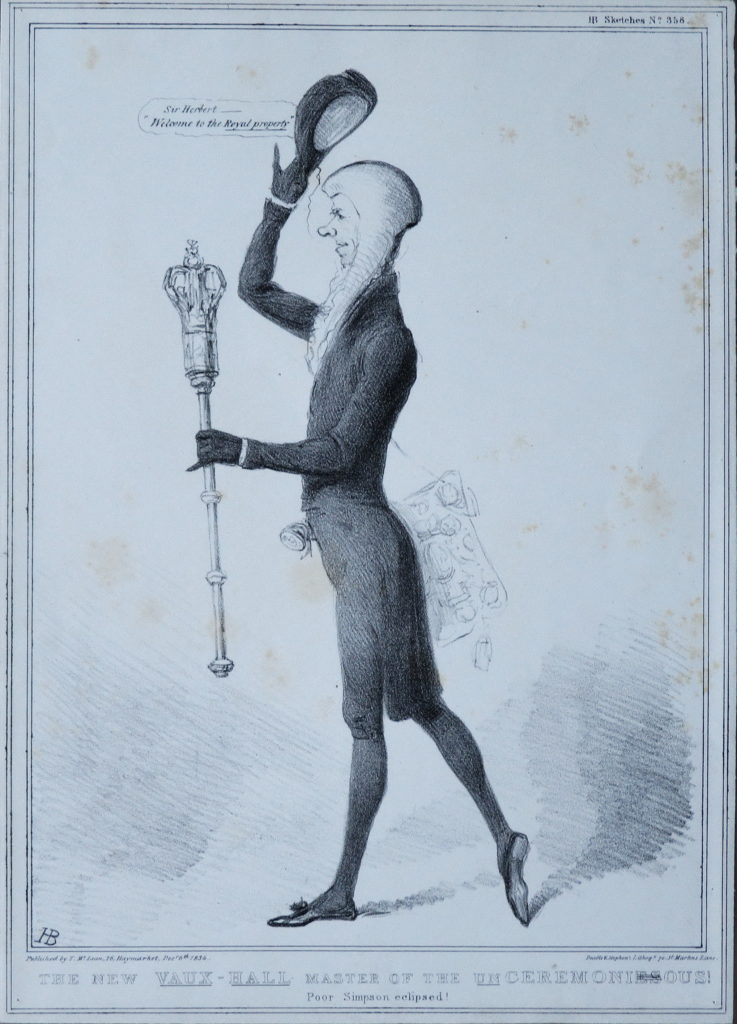

The success of Simpson’s transformation was achieved by a double disguise – his determined hiding of his Christian name behind those initials, and his invariable uniform when seen in public – an undoubtedly theatrical and old-fashioned costume of black buckled knee-breeches and stockings, patent pumps with black bows, a white waistcoat and black morning coat, all close-fitting, with a cascading cravat at his neck, a watch-chain loaded with seals and fobs, an occasional seasonal nosegay at the button-hole, and a black beaver hat on (or most often courteously lifted off) his bald head; the ensemble was completed with white gloves and a tasselled silver-mounted ebony cane [Fig.1] – a character costume if ever there was one. The costume is first visually recorded in the portrait of Simpson created by J.W. Gear for his 1833 Benefit Night at Vauxhall [Fig 2], and is celebrated in poetry by a contemporary versifier:

ON THE INCOMPARABLE PORTRAIT OF THE INIMITABLE

“C.H. SIMPSON, ESQ., MASTER OF THE CEREMONIES AT

VAUXHALL.”

BY THE AUTHOR OF “CRAYONS FROM THE COMMONS”

The painter’s art unrivall’d we behold,

In seizing all that Nature’s hand could mould –

In tracing forth each point on which we gaze,

While matchless Simpson fills us with amaze –

Simpson, who stands proclaim’d, by one and all,

The glorious guardian genius of Vauxhall!

That saltant form, with agile gait, appears,

A prancing comment on advancing years;

That face, despite of wrinkles, rude is seen,

A strong, perennial, stubborn evergreen.

The more we gaze, the more must we admire

Each nicer touch that pencils his attire:

His pliant pumps upon their surface show

Two tasteful knots, full bunching to a bow;

His silken hose are soften’d on the sight,

In sable contrast with the buckle bright,

Which, in its sparkling vividness, we see

Reflecting transient lustre from his knee;

His coat enhances his transcendant vest –

A costly brilliant blazes on his breast;

His hat, with rim convolv’d on either side,

Completes the acmé of his conscious pride.

But all the powers of graphic song were vain

To tune each movement of his ebon cane,

As onward still in greeting mood he trips,

The “Royal Gardens” on his lauding lips.

Ne’er could the Muse, in numbers meet, pourtray

The prostrate homage, studious of display,

Evinc’d, as each beholder must allow,

Within the circle of his sweeping bow.

These features rare the Sister Art alone

Describes, by means peculiarly her own:

Fam’d Simpson swells in ev’ry cut and caper,

The crowning climax of pictorial paper.

Such the great man whom fashion proudly stamps,

Flaming beneath five hundred thousand lamps.

Just as the real Jonathan Tyers, the temperamental and depressive founder of the gardens in the 1730s, had to hide behind the mask of the urbane host and gentleman patron of the arts, so the real C.H. Simpson, doubtless scarred by his brief but violent experience of warfare as a child of 12, and depressed by his lack of acting success, hid himself behind the comic figure of his Master of Ceremonies – what Thackeray in Vanity Fair called ‘The gentle Simpson, that kind smiling idiot’. This character became famous for his excessive and unfailing politeness to everybody, an obsessive courtesy and ridiculous, fawning sycophancy; invariable behaviour that visitors would travel for miles just to see and to experience. Simpson was a phenomenon, a wonder, a spectacle in his own right; such was the impression made by his character that he soon morphed into a trade-mark for Vauxhall, a universally recognised logo. This fact was exploited and encouraged by John William Gear (c.1799–1866) painter, printer, and publisher, who created the full-length lithograph portrait of Simpson (see Fig. 2), first issued in 1831 for sale at the gardens, and referred to by the Gentleman’s Magazine as ‘grotesque’, which here means something more akin to ‘caricature’. As Simpson himself had an interest in its sale, he wrote letters, in his own idiosyncratic style, to his friends in the press: “Highly esteemed Sir – With a heart filled with every sentiment of the most profound gratitude for all your manifold kindnesses to me, I most respectfully, and in the most humble and submissive manner, entreat, kind Sir, that your well-known goodness of heart will be graciously pleased to condescend to accept the enclosed portrait of myself.”

He goes on to explain that the print is for sale at two shillings, and to ask the editor to write up the print in his next edition.[4]Lambeth Archives, Vauxhall Gardens Albums V, f.185 This, of course, following such a polite entreaty, they were delighted to do. Simpson’s marketing skills were not far short of those of Jonathan Tyers himself, and used to equal effect – further evidence of the intelligence and skills of the man behind the disguise.

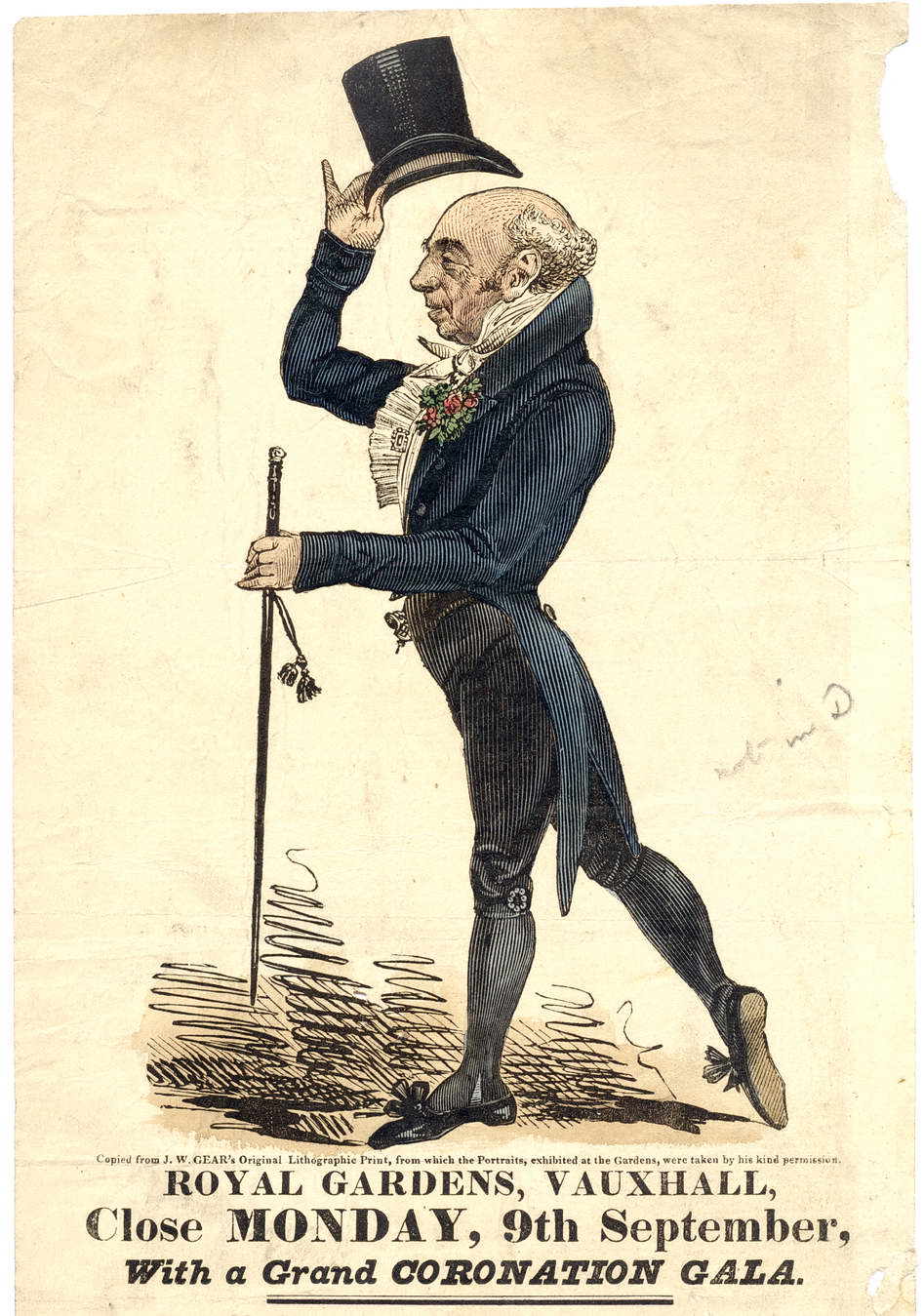

The genius of Gear’s composition is that it is not a straight portrait, but rather a full-length silhouette, catching the sitter, from his left side, in his characteristic pose about to bow to a visitor, his right foot behind the left, his hat lifted, his cane held off the floor like a staff of office, creating one of the most striking and memorable portraits of the period.

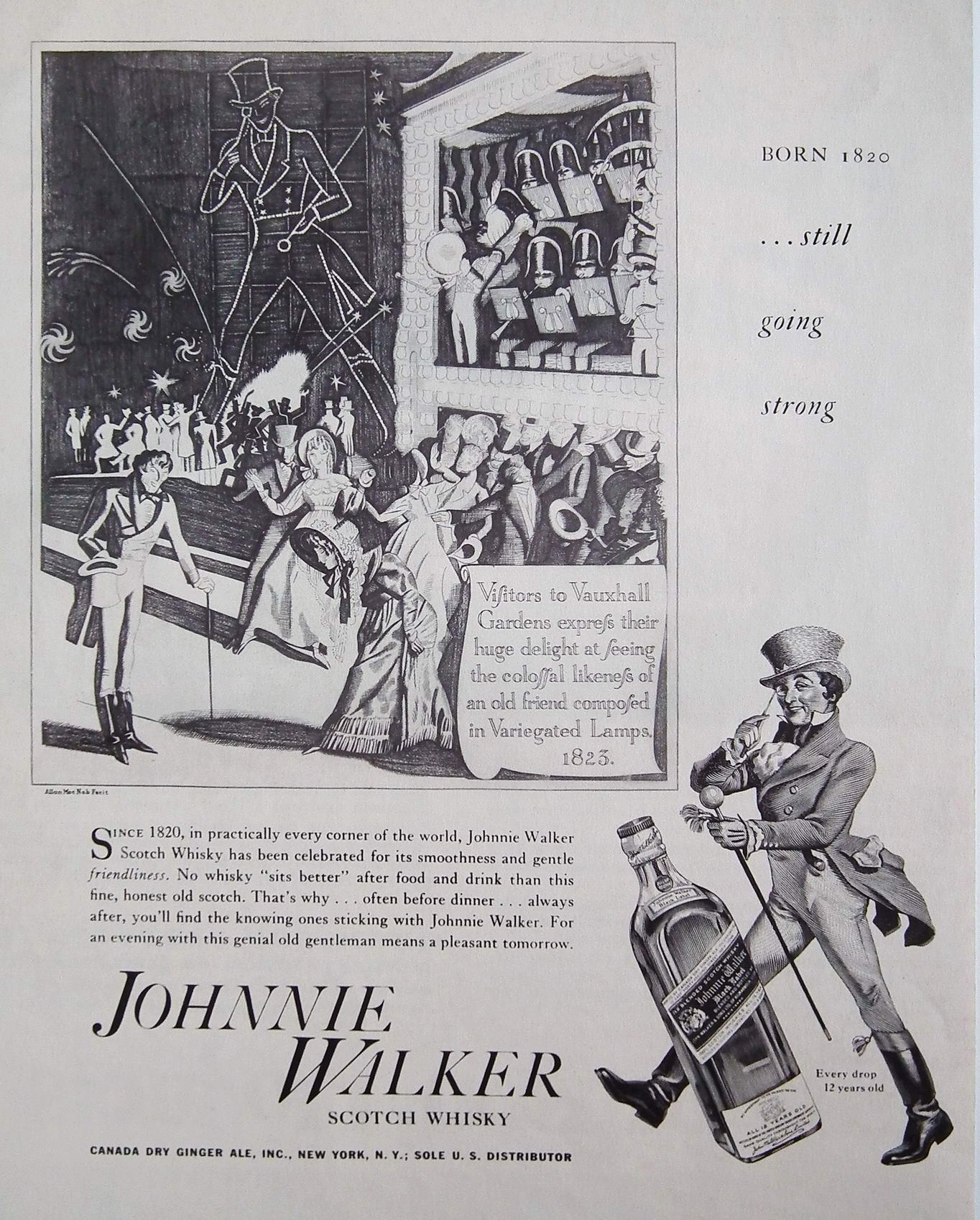

So memorable was it that Gear’s silhouette of Simpson went on to inspire another, possibly even more famous logo; when the cartoonist Tom Browne was commissioned to produce a marketing device for a Scotch Whisky company in 1908, he brought Gear’s portrait to mind, and created the famous ‘Striding Man’ logo for Johnnie Walker. Reinforcing this link, a magazine advertisement for the Scotch in the 1930s actually adapted the 1833 Robert Cruikshank scene of Simpson welcoming the Duke of Wellington to Vauxhall, against the backdrop of the Orchestra and the gigantic illuminated figure of Simpson created for his benefit night [Fig. 3], replacing the illuminated Simpson with the new figure. With its strapline of “Born 1820 . . . still going strong”, Johnnie Walker’s early publicity regularly harked back to an earlier more elegant age, and Vauxhall Gardens, itself still going strong in 1820 and after, fitted the bill very well [Fig. 4].

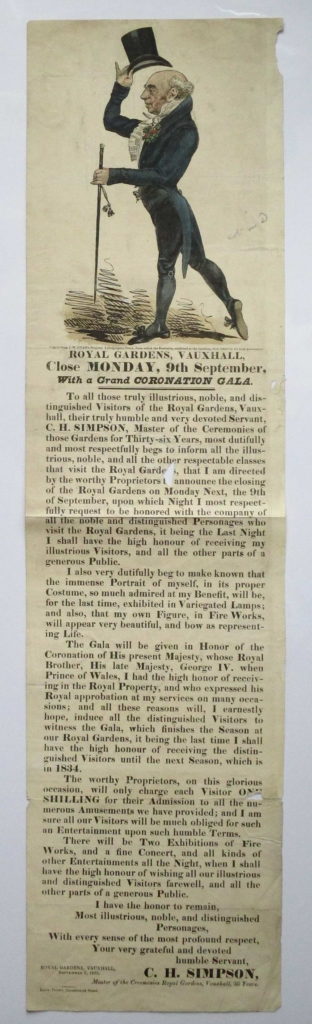

The Gear silhouette was adapted by other artists, especially in designs for Vauxhall’s publicity. The best example of this is the handbill advertising the Grand Coronation Gala of 9 September 1833, the closing night of the season, headed by Simpson’s striding figure [Fig. 5] Everybody would have been immediately aware that this was a Vauxhall handbill, but it also gave the image itself an added currency. The text of the handbill is in the form of a letter from Simpson to Vauxhall’s patrons, in his usual obsequious style, designed, as always, to make people smile:

“To all those truly illustrious, noble, and distinguished Visitors of the Royal Gardens, Vauxhall, their truly humble and very devoted Servant, C.H. Simpson, Master of the Ceremonies at those Gardens for Thirty-six Years, most dutifully and most respectfully begs to inform all the illustrious, noble, and all the other respectable classes that visit the Royal Gardens, that I am directed by the worthy Proprietors to announce the closing of the Royal Gardens on Monday next . . .” [Fig. 6]

The ‘letter’ goes on to enumerate the attractions of the Coronation Gala in a similar style.

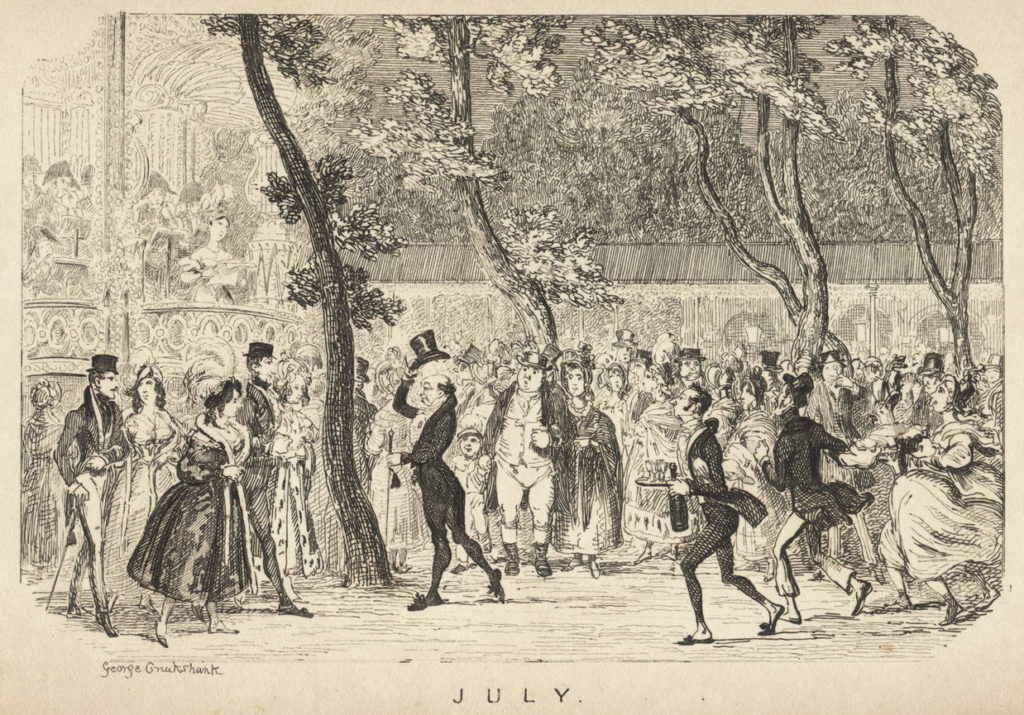

Even such a distinguished artist as George Cruikshank borrowed the image, realising that it was a useful shorthand for the location; in his Comic Almanack for July 1835, the main illustration shows a crowded Vauxhall Gardens, as viewed from the entrance to the Rotunda looking south, with the recognisable figure in the centre, bowing to a middle-class couple, much to the amazement of a rustic couple behind him, obviously on their first visit. [Fig. 7]

Simpson, of bowing and letter-writing celebrity, was for years an attraction. It is impossible to conceive anything more solemnly absurd, more inexpressibly ludicrous, than this little fellow, who paraded in the gardens in unexceptionable black tights, carrying his beaver up a foot above his head, and bowing to everything he saw, animate or inanimate, from a lord to a lamp-post…” —Sunday Times, 6 October 1844.

This is the kind of publicity that Simpson’s character consistently gained for Vauxhall throughout his career, and which made an incalculable contribution to the continuing success of the Gardens right up to the accession of Queen Victoria. Because of Simpson’s starring role at Vauxhall, and his ability to keep order, alongside major attractions like Charles Green’s balloon ascents, Vauxhall Gardens could contribute hugely to the local economy of Vauxhall for several decades beyond its realistic expectations.

First employed at Vauxhall Gardens aged only 27, Simpson stayed in post for the remarkable total of 38 years, a reign as long and as notable as that of Jonathan Tyers himself. Even though he was employed from the opening night (3 June) of 1797, it is not until much later that we hear anything significant about him. This appears to be because his earlier role at the gardens was not so much in the public eye as it later became. When he appeared at the Surrey Magistrates’ Quarter Sessions on 14 October 1811 as the ‘accuser’, along with constable James Glannon, of three of Vauxhall’s lamplighters for stealing lamp-oil and wick-cotton, he was called the ‘Superintendent at Vauxhall Gardens’; this makes absolute sense when taken together with the verse in ‘Simpson the Beau’ quoted below, where he is called the ‘Chief inspector of fowls, ham and beef’ and the taster of punch; he was, it appears, in charge of quality control of the refreshments, and maybe of the junior staff as well.

His first job at Vauxhall, then, was not Master of Ceremonies at all, but something more like a front-of-house manager, in which role, the public would have known little of him. Of the accused lamplighters, one was acquitted, one was found guilty and given three months hard labour, and the ring-leader of the gang, one Samuel Brown, was found guilty and sentenced to 12 months hard labour and public whipping for 150 yards in Kennington Lane.

As the front-of-house manager, Simpson would have worked alongside a business manager – soon after Simpson’s arrival, the name of James Perkins (or Parkins) appears as ‘manager’ on insurance documents and other official and financial papers. During Simpson’s time, the situation of business manager or treasurer changed hands many times. He also saw the proprietorship change hands from the great-grandsons of Jonathan Tyers to the business partnership of Frederick Gye and Richard Hughes.

Over the next decade or so, Simpson must have transformed his chosen job into something much more public, almost a maitre d’hôte, in which the satisfaction of Vauxhall’s customers, rather than the supervision of his juniors, became his main concern. From this, it would have been a short step to M.C., which is exactly what he is called in the in-house accounts for 1822/23, preserved in the Shaw collection at Harvard[5]vol. III, p.35; as M.C. he was earning £34 per season, with a bonus of £10. In addition, and in common with other members of the senior staff, Simpson was allowed free refreshments. The fact that he was employed for the season, rather than permanently, may suggest that he was still finding work, maybe on the stage, outside the Vauxhall season. His colleagues in 1823 – the Treasurer William Rouse and the Manager Mr Ghent – both appear to have been full-time appointments, the first earning a salary of £500, and the second £100 per annum. The 1823 season ran from 19 May until 12 September – 17 weeks in all, so Simpson’s pro rata salary was the equivalent of Mr Ghent’s.

We find no mention of Simpson in the press coverage of Vauxhall until the last night celebrations of the 1826 season, attended by 700 visitors. A newspaper report on the following day bemoans the fact that the proprietors had probably made very little profit that season, but “To Mr Simpson, and indeed to every gentleman of the establishment, the thanks of the visitors are due for the zeal, promptitude and regularity with which their various duties have been executed.”[6]Unidentified cutting in the J.H. Burn collection, British Library, Cup.401.K7, fo.445. It was Simpson who received the credit for the smooth running of the gardens.

Just four years later, Simpson had already become the almost mythical ‘presiding deity’ at Vauxhall for which he is best known today, his behaviour and character well-worn subjects for comedy and satire. It was in its issue of 7 August 1830, only three weeks after the funeral of King George IV, that The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction published a comic article called ‘The Bower – A Vauxhall View.’ Anybody reading that title would ordinarily have expected the subject to be the venerable pleasure garden itself, but the joke, possibly in its first of many appearances, was broken to the reader at the end of the first paragraph – “The Bower that we allude to, is not that wherein hearts and promises are sometimes broken, which birds delight to haunt, and bards to describe. No, it is merely a human being, a living bower – an acquaintance most probably of the reader’s; – we mean, in short, the Master of the Ceremonies at Vauxhall Gardens!”

The Mirror article, while acknowledging that there were few people who did not know of Simpson as a civilised and civilising influence at Vauxhall, goes on to enumerate several mysteries about ‘our kind and accomplished friend.’ The writer describes how Simpson would appear like magic at your supper-box and politely enquire whether there was anything he could do to improve the evening of the visitors dining there. He describes Simpson’s constant bowing and smiling, and wonders how he could keep it up quite so constantly, even when wine is spilled on his pumps or over his immaculate white waistcoat, at which ‘he smiles as if you had conferred a favour on him, and bows himself dry again.’ Another mystery was where Simpson went when it was not supper-time – he was seldom seen when not ensuring that visitors were enjoying their suppers. But the greatest mystery of all, according to the Mirror, was where Simpson disappeared to out of season – ‘He and the lights go out together.’ The mystery was as great as that of the migrations of birds. It is now clear to historians that Simpson, during the Vauxhall season, rented rooms at 12 Lambeth Walk, and for the rest of the year returned to his own residence off the Mile End Road, more or less on the site of the present Harford Street – the address then was 4 Regent Place, from where Simpson wrote to his employer Frederick Gye in 1826 thanking him for his continued employment, and pointing out the ‘truly enormous and almost useless expenditure’ on Vauxhall’s force of constables at that time.[7]Harvard, Shaw Collection, vol. III, p.90. Later he moved to more salubrious, though less rural surroundings at 31 Holywell Street, Strand, where he is recorded by 1830.

While the letter to Frederick Gye is authenticated by the recipient, it is frequently difficult, because his writing style was so distinctive and so easily parodied, to determine whether published letters, articles or other writings signed by Simpson are, in fact, by him. There was a regular flow of writings in Simpson’s idiosyncratic style, and, often, replies and disclaimers apparently from him as well, all lightly satirical. This makes it hard to ascertain what is true and what is not. The climax of this series is Simpson’s ‘autobiography’, called The Surprising Life and Adventures of C. H. Simpson, Master of the Ceremonies at the Royal Gardens, Vauxhall, from his earliest Youth to the sixty-Fifth Year of his Age. Written by Myself, and dedicated to my friend, the Editor of “The Times”, published by W. Strange in 1835. This is a very kind parody, gently comic even today, and completely inoffensive. Its leitmotif, repeated many times, is the fact that he was Master of the Ceremonies at Vauxhall for 38 years, and that he is now in the 65th year of his life. The autobiography (only 30-odd pages in all) is repetitive, abject, self-effacing, effusive, self-caricaturing; the subject sometimes clearly mistakes criticism for praise, and teasing for friendship. It is entirely possible, even probable, that all these ‘hoax’ writings, even including the Mirror article, were actually by Simpson himself, as self-caricature. If I am right in assuming that his ‘Master of Ceremonies’ was a character role he created and adopted, then it is equally likely that the various writings signed by him, even the ‘autobiography’ were merely building up that character, making it better-known and better loved – all part of his continuing campaign to promote the Gardens. The C.H. Simpson ‘so long the butt of the newspaper wits’, as the Gentleman’s Magazine put it, may quite credibly have been entirely the creation of a minor actor best known for comedy valets or dapper young gentlemen.

His date of birth is given in his autobiography as 1 April 1770, although we now know that this April Fools’ Day birthday is part of the author’s joke. At least the year is correct, but the real date was just a week earlier, the 26th March. In early childhood, the author reports, Simpson had apparently so well mastered the art of bowing ‘that my respected, elegant, and accomplished parents Denominated me “the Bower of Bliss”. We are told that Simpson was considered “a clever child” because he once burned his hands in the fire by accident “and actually took them out again without being told, and this was considered very shrewd and clever in so young a Child.” One possibly mythical event of his childhood was carried in the Magazine of Curiosity and Wonder (an illustrated penny magazine produced by Thomas Prest and published by George Drake) in 1836, apparently quoting an earlier press report:

Yesterday evening as the infant son of Mr. Simpson, residing in Westminster, was playing on a bed in the nursery, he was suddenly rolled off into a large tub, which was full of water, and in consequence of the size of the vessel, the accident would most certainly have been attended with fatal consequences, had not a fine dog, belonging to the family, observed the peril of the child, and rescued it from its dangerous situation.” —Quoted, from the Morning Advertiser of August 1773, in The Magazine of Curiosity and Wonder, Thursday January 7, 1836, p.82.

The dog, named William Tell, lived on to great old age after this event. Even though this story stretches our credibility, there is enough factually correct material in the autobiography to suggest that the author, whether Simpson himself or not, knew a great deal about his subject.

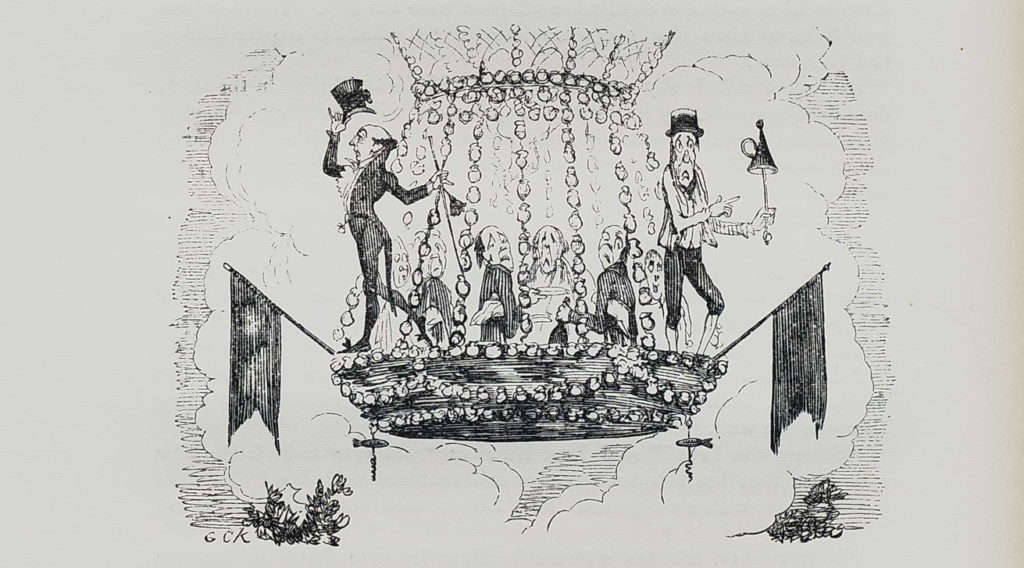

‘An interesting and unique Gala’ at Vauxhall Gardens on 19 August 1833 marked the apogee of Simpson’s long career [Fig.8]. The attractions for the occasion included a huge illuminated transparent painting of the city of Antwerp, a ‘water scene’ representing the Triumph of Britannia “amidst the Discharge of large bodies of Water, Explosion of Bombs, Shells, Rockets, Coloured Fires, &c., with music from the military band of the Grand Duke of Darmstadt. It is for this spectacular occasion that the creation of Simpson’s character was truly completed, and his myth made immortal. The first ‘Benefit night’ so far given to an individual, this occasion represented almost an apotheosis of the famed Master of Ceremonies, at which he was represented not only in paint, but also in fireworks, in prints, in poetry and in song. Often called ‘larger-than-life’, at his Benefit, that is how he was depicted, 15 metres tall.

The comic singer W.H. “Billy” Williams, who performed regularly at Vauxhall between 1823 and 1836, was widely famed for a song of 1833 in honour of Simpson, entitled “What Think you of Simpson the Beau?” – an ‘Historical Comical Comic Ballad’, written by Captain Stone, composed by J. Blewitt[8]Jonathan or Jonas Blewitt (1782-1853) was principle composer to Vauxhall between 1828 and 1839, and ‘Dedicated to the Count de Grasse by Col. Bolsover of the Horse Marines.’ The only complete copy I have found is in the Shaw Collection, Harvard Theatre Collection[9]IX, p.198-200, and I transcribe it here in full, not because of any inherent quality, but because it is not otherwise easily obtainable, even online. Apart from taking up the joke of Simpson being Vauxhall’s great ‘bower’, this rather poor song includes several biographical details about Simpson, including that he was only four feet seven inches (1.4m) high, although, to be fair, this does refer to the time when he was only a boy in the navy so he may have gained some height afterwards. He was, though, known to be shorter than average, and slightly over-weight.

1. What think you of Simpson the beau?

Who at Vauxhall was always the go

He’s an elegant Man, For a Lady with a fan

Or a Dandy who sues for a Box.

Chorus: Off he goes on his toes

With his pretty black Cloaths

Lord! how vain of his Cane!

See he’s coming again

What think you of Simpson the beau? O

O what think you of Simpson the beau?

2. For thirty six years he’s been Chief

Inspector of Fowls Ham and Beef

Besides he’s the knack

As grand taster of rack

To infuse all with spirits around

Off he goes . . .

3. To the Noble, accomplish’d, sweet Ladies

Who prized this Lothario in gay days

To the Princes of blood

Even those ‘fore the flood

He offers his very best bow

Off he goes . . .

4. He blesses the worthy Proprietors

Bows, flatters, and quiets e’en rioters

And tho’ he looks sable

To Cane he’s quite able

All those who stick up for a fight.

Off he goes . . .

5. With RODNEY he kicked up a row

Which his friends of the mess must allow

He swears by the mass

That he nibbled long Grasse

What a Nebuchadnezzar was he

Off he goes . . .

6. This Monster was five feet eleven

Brave SIMPSON just four feet & seven

How horrid the fight

From morn until night

Which raised mighty SIMPSON to Glory

Off he goes . . .

7. To Music he moves quite Stick-ato

In toe toe you’ll find him legato

Though he’s not such a Flat

But he knows what he’s at

For his key has been ever C. Sharp

Off he goes . . .

8. Even Artists their time to beguile

Have Painted brave SIMPSON in Oil

And by aid of the lamp

Given nature a stamp

And raised him just thirty feet high

Off he goes . . .

9. To stand high is the wish of us all

But SIMPSON you’re growing too tall

Indeed such devices

Are worthy high prices

And not to be treated so light

Off he goes . . .

11. Vauxhall hath its bowers and flowers

Its Rockets, and shelters from showers –

But SIMPSON away

All would fall to decay –

For he’s surely the gardens – best bower

Off he goes . . .

12. God bless all his friends and his backers,

And those who exalt him in Crackers

Tho’ burning the shame

It raises his fame

So adieu to this wonderful Star

Off he goes see his toes

Lord he’s sing’d his black Cloaths

All in pain for his Cane !

We shan’t see it again

What think you of SIMPSON the beau ?

Verse 6 of this song refers to the massive portrait of Simpson, 30 feet high and illuminated with lamps. This was the figure, possibly painted by E.W. Cocks, director of the scene-painting department at Vauxhall, which appears in the background of the engraving showing Simpson welcoming the Duke of Wellington to his benefit night on 19 August 1833 [see Fig. 3]. For this very special occasion, portraits of Simpson were an integral part of the decorations – not only this static illuminated figure behind the Orchestra, but also an even larger figure, 45 feet high, in fireworks, designed by the Vauxhall pyrotechnician Joseph Southby to mechanically bow like Simpson himself; on the same occasion, according to The Times (Aug 20, 1833) “thirty-five landscape illustrations of the splendid Simpson, graced the quadrangle of the Royal Gardens”, judging by their number, these must have decorated (temporarily) the remaining supper-boxes to the north and south of the central quadrangle or ‘Grove’, in place of the old-fashioned paintings by Francis Hayman.

Although Simpson was the only individual, up to that time, granted a Benefit Night by the proprietors, and despite his fame and popularity, it was not the overwhelming success that it should have been, partly because of the weather, which threatened rain. The Benefit was originally intended to mark Simpson’s retirement from Vauxhall – an event almost as unthinkable as the ravens retiring from the Tower of London. In the event, however, Simpson preferred not to retire, but returned the following season, and the one after that. The total take for Simpson’s 1833 Benefit Night was £2,572; with tickets costing four shillings (the usual price of admission at that period), this suggests that over 12,000 visitors attended – a huge number in view of the unfavourable weather. Ticket no.1,609 is preserved in the Peter Jackson Collection[10]Image online at the Look and Learn History Picture Library, ref: XJ 132589. Because the weather had been against them, the proprietors gave Simpson a second benefit night on 21 July the following year, with special performances by some of the greatest musicians and singers of the day – Madame Pasta, Madame Gandolfi (or Grandolfi), Signor de Begnis and Niccolo Paganini all performed for it without a fee.[11]Lambeth Archives, Vauxhall Gardens Albums IV, f.211. Together, these two occasions would have allowed Simpson to retire in comfort, but he chose to continue his duties until his death in 1835, presumably relishing the celebrity and status it gave him.

To honour his remarkable talents and qualities, a plaster bust of Simpson was commissioned by the proprietors in 1834 from Lewis Brucciani, of 5 Little Russell Street, to be placed in the Saloon. This bust does not appear in any of the visual documentation, and there is no sign of it thereafter – its present whereabouts are unknown; it may eventually have been included amongst the ‘Busts of Eminent Men’ sold by Drivers on 29 August 1859. At the earlier Drivers sale on the premises on 12 October 1841, ‘four busts of the celebrated Simpson’ (lot 142) were sold for ten shillings; these may have been small versions of Brucciani’s original, intended for sale to the public.

A final episode in Simpson’s career does nothing to dilute the character of his M.C., and was one of the most newsworthy. In 1833, he announced his intention of ascending in Charles Green’s gas balloon. He was clearly nervous when the day came – ‘his whole person shaking like the skeleton of Jerry Abershaw in a high wind’ – but he was fortunately prevented from risking his neck by ‘a thousand amiable, interesting, and beautiful females’ who rushed forward to stop him going; or, depending on which explanation you prefer, by a certain Mr Cave, who offered 25 guineas to go up in his place, or even, less credibly, by a group of English aristocrats who thought it undignified for Simpson to ascend in a balloon. For this occasion he had exchanged his usual sober attire for something rather more colourful; ‘rose-coloured inexpressibles[breeches], silk stockings, and jacket of ethereal blue, with a splendid yellow dahlia (or dandelion) in his button-hole.’ He had already removed his ‘shallow of green satin (a low-crowned hat, tapering down to the wide curled brim), decorated with purple ostrich feathers.’[12]Unidentified cutting of Aug 17, 1835, Lambeth Archives, Vauxhall Gardens Albums II, f.10. So Simpson did, at least once, wear a different costume, but this one must have been equally, or even more flamboyant than his usual uniform. On the occasion of his re-assumption of his duties on the opening night of his final year, 1835, Simpson appears to let his standards drop one more time, and to have made himself indistinguishable from other men in the crowd, maybe to reveal something of the real man, maybe just to give journalists something to write about. He is described in a press report of 19 May 1835[13]Lambeth Archives, Minet volume II, f.82. as ‘not in his usual costume…but, as much interest will be felt about his appearance, we think it right to state that he wore an undress black coat, light waistcoat, and fawn-coloured continuations [trousers]; his hair was unpowdered, and his hat was of smaller dimensions than that which last season formed so prominent a feature in the attractions of the gardens.’

It was on Christmas Day 1835, well outside the Vauxhall season, that C.H. Simpson died, at his home, 31 Holywell Street, Strand (where he had lived for at least five years), aged just 65, childless and unmarried. He was buried at St John the Evangelist, Westminster, on 31 December, almost within sight of Vauxhall Gardens across the river. I know of only one surviving relic of Simpson – his 1808 oval ivory staff-pass to Vauxhall Gardens is preserved at the British Museum, in the Montague Guest Collection.[14]MG 691.

Following Simpson’s demise, one of the Vauxhall’s waiters, ‘Little’ John Lewis smartened himself up, started using Rowland’s kalydor (a hair oil), wore whiter and more starched cravats, and exchanged his ‘rudely carved pantaloons and gaiters’ for ‘the Nugee coat and a pair of O’Shaughnessy pumps’, all in the hope of sliding seamlessly into Simpson’s place. But Lewis was not the proprietors’ choice, and a certain Edward Fisher Longshawe is recorded on handbills of 1836 as the new M.C. After six years, during which several professional actors took on the role, the job was offered to Henry Widdicomb (1813–1868), still Circus Master of Astley’s Amphitheatre. Widdicomb, who had himself appeared in pantomime when young, held down the two jobs simultaneously, suggesting that neither venue was a full-time commitment for him, as it had been for his illustrious predecessor.

Simpson’s ghost was evoked by cartoonists [Figs. 9 & 10], poets and songsters writing of Vauxhall; the famous silhouette continued to be used for political satire [Fig. 11], and the man himself was long remembered by Vauxhall’s regulars. Theodosius Purland wrote to his friend John Fillinham, on the occasion of the final closure of the gardens, on 25 July 1859, “we will drink to the immortal memory of Jonathan Tyers – Hogarth and Simpson! Yes we will do all that befits us to do on the melancholy occasion.”[15]Coke & Borg, Vauxhall Gardens, A History, Yale University Press (2011), p.353.

To many people, Simpson was Vauxhall, as Vauxhall was Simpson – to continue to open the gardens after his death was meaningless madness; nobody could take his place. Without his greeting and his obsequious letters, Vauxhall was nothing. Indeed, only five years after Simpson died, the proprietors were declared bankrupt, and the gardens were closed for a whole season. A series of different lessees took on the venue, but none could make it pay, and the gardens inevitably closed for ever in 1859 after a fitful final two decades.

Simpson’s celebrity was such that he was included in the works of W.M. Thackeray, of Charles Dickens, and of several historians of 19th century London. Even today, Simpson is still remembered in Vauxhall – Simpson House, the biggest and most prominent apartment block on the 1930s Vauxhall Gardens Estate, overlooking the site of the pleasure garden, is named after him, an honour he shares with several of the better-known singers of his day.

For much of the information in this essay, I gratefully acknowledge the kind assistance and hard work of Dr Alan Borg, Karen Coke, and Dr Pieter van der Merwe MBE, DL. of the Royal Museums, Greenwich.

Except for the two items from Cruikshank’s Comic Almanack 1842, which belong to a friend of mine, J.J. Visser in Friesland, The Netherlands, all images are taken from originals in my own Vauxhall Gardens collection, and are copyright to that collection.

© David E. Coke, 7 April 2019.

References

| ↑1 | Volume V. (ns) Feb. 1836, p.210. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | William Clarke, Every Night Book, or, Life After Dark. London: T. Richardson, 1827, p.187. |

| ↑3 | Lambeth Archives, Vauxhall Gardens Albums V, f.226. |

| ↑4 | Lambeth Archives, Vauxhall Gardens Albums V, f.185 |

| ↑5 | vol. III, p.35 |

| ↑6 | Unidentified cutting in the J.H. Burn collection, British Library, Cup.401.K7, fo.445. |

| ↑7 | Harvard, Shaw Collection, vol. III, p.90. |

| ↑8 | Jonathan or Jonas Blewitt (1782-1853) was principle composer to Vauxhall between 1828 and 1839 |

| ↑9 | IX, p.198-200 |

| ↑10 | Image online at the Look and Learn History Picture Library, ref: XJ 132589. |

| ↑11 | Lambeth Archives, Vauxhall Gardens Albums IV, f.211. |

| ↑12 | Unidentified cutting of Aug 17, 1835, Lambeth Archives, Vauxhall Gardens Albums II, f.10. |

| ↑13 | Lambeth Archives, Minet volume II, f.82. |

| ↑14 | MG 691. |

| ↑15 | Coke & Borg, Vauxhall Gardens, A History, Yale University Press (2011), p.353. |