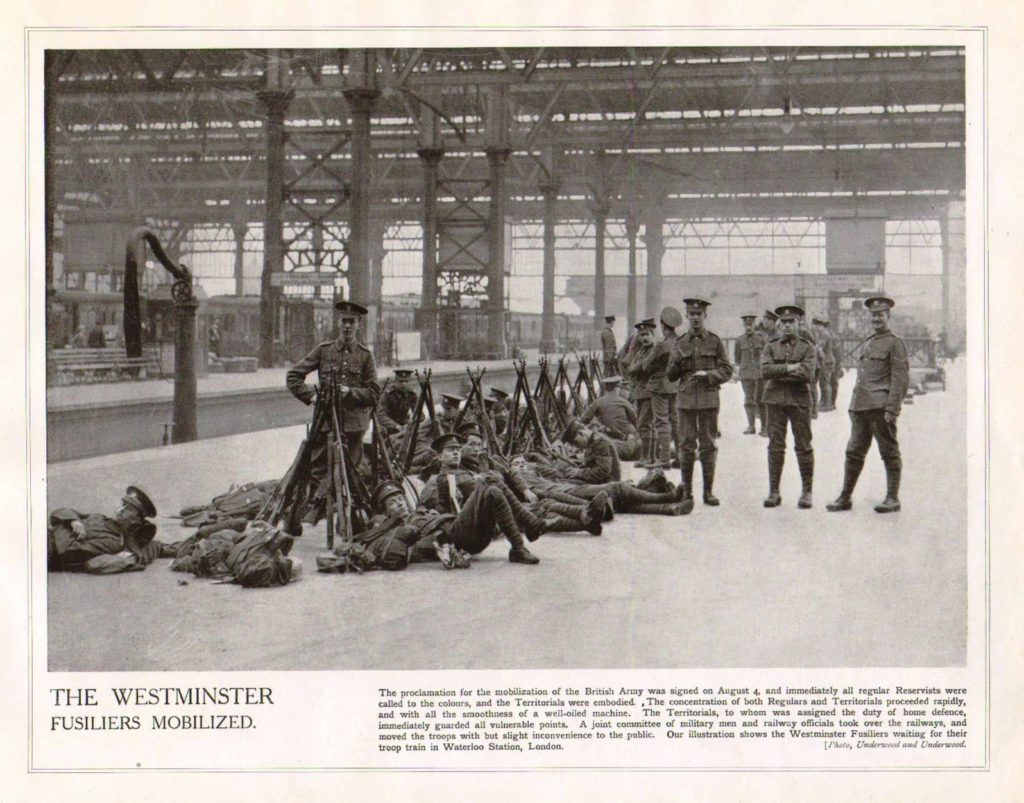

With the coming of the Great War of 1914-1918 the streets of London were soon to be thronged with what Jerry White, Professor of History at London University, terms “a heady mix of soldiers and women”. The ready availability of sex, amateur as well as professional, ignited a moral panic. Nowhere was this more so than around Waterloo Station, a principal departure point for the Front as well as destination for men coming home on leave. Professor White’s many books about the capital include Zeppelin Nights: London in the First World War.

by Jerry White

When we think about London and war we tend to think just of the Blitz of September 1940 to May 1941, an event that has overshadowed not just the rest of the Second World War but the whole of the First. In fact, the First World war was a momentous time for London and Londoners. The war transformed every feature of Londoners’ lives from the day after the declaration of war in August 1914; but even more important, the changes brought about by war redefined the future of London for a generation and beyond.

It’s possible to see one enduring change, and a great deal of drama amid the bustle of everyday life, in something that went to the heart of the experience of soldiers in London during the First World War. That was sex, especially sex for sale, and specifically sex for sale in the streets of North Lambeth around Waterloo Station.

It’s a more complicated subject than might seem evident at first sight. For in many ways this was an issue that seemed to go to the heart of what Britain was fighting for: what sort of nation it had been before 4 August 1914 and what sort of nation would emerge once peace had been declared, whenever that might be. For this was a war that many felt was being waged to restore morality to a nation that was thought to have slipped back from the standards of Victorian Britain. And of all the questions of morality to raise most anxiety in this war it was sexual licence that worried puritans and moral reformers most.

The heady mix of soldiers and women had of course worried the generals too, if only because so many had been brought up with puritan ideals of an unremitting kind. There are many instances but none more famous than Lord Horatio Kitchener of Khartoum, who had walked in the steps of one of the greatest of all soldier-saints General Charles George Gordon, and was made Secretary of State for War on 5 August. He was unmarried and a temperance advocate. Kitchener famously urged sexual abstinence on his troops and refused to equip the British Expeditionary Force of 1914 with condoms as prophylactics against venereal disease, alone among the rival armies of Europe, preferring to rely on exhortation: ‘In this new experience you may find temptations both in wine and women. You must entirely resist both temptations, and, while treating all women with perfect courtesy, you should avoid any intimacy.’

Of course, it didn’t work. But in this war, when the sacrifices of soldiers were plain for everyone to see and every single family in the land to experience, it was not the saintly soldier giving way to ‘temptations’ that faced criticism. It was the women temptresses who were most feared, vilified and disciplined. And it was in London, where the figure of the prostitute had long been a cause of moral queasiness, that fear, vilification and discipline were all most sharply and painfully experienced.

Fear, then, seemed to be all over the streets of London and almost from the moment war was declared. There would be more men in London during the four years and more of the Great War than at any previous time in history. Unsurprisingly they attracted young women too, and for a variety of reasons. ‘Khaki Fever’, girls chasing soldiers, had been a worry from the very outset, and something like it continued throughout the war. Many observers were struck by the change in the London streets brought about by the war: ‘You have vast numbers of soldiers on leave, and you have a large number of young women living a more independent life than they were in peace time’, so that ‘the streets are very much more crowded now.’ Among the crowds of women, those concerned with the changing morality of wartime London thought that ‘since the war, and perhaps for some years before the war, there were considerable numbers of young girls who were, if not adopting the profession of prostitutes, at any rate leading immoral lives. There is a very much larger number now of young girls on the streets than there were, say 20 years ago – quite young girls of 15, 16 and 17 years of age.’ Challenged to provide evidence for this confident assertion Sir Ernley Blackwell, a junior Home Office minister, offered the experience of a man about town.

I would arrive at it simply by walking along the streets and taking notice myself. I see that there are. I do not think anyone who has known the London streets for the last 20 or 30 years could avoid being struck by the fact that, whereas 20 or 25 years ago the streets of the West End between 8 and 12 o’clock were full of women, professional prostitutes, but women of considerable age, well over 25 years of age, now I should say there are far fewer of these regular professional prostitutes and many more quite young girls, whom you did not see in old days….

A somewhat different view of the same phenomenon was given by Miss Elithe MacDougall, a Scottish social worker who knew the girls of Lambeth well and who in October 1918 was ‘Lady Assistant’ to the Metropolitan Police. She agreed that the age of prostitutes in London had come down since the start of the war but on the other hand thought ‘a great many young girls do not take money at all if they go wrong’ with soldiers: ‘They are simply out for a lark.’

These larks took place pretty much everywhere in London County and no doubt beyond. But the war brought with it new fields of action and intensified familiar theatres. The streets around the London railway stations, for instance, had long presented opportunities for sexual encounters but the war, with its extraordinary demands, thrust out new marketplaces in every direction. So around Victoria station, for instance, traditional soliciting walks at Terminus Place and Vauxhall Bridge Road and the cheap lodging district of Pimlico, were extended into Horseferry Road, encouraged by the ANZAC (Australia and New Zealand Army Corps) headquarters there. It was said that ‘the evil is to a large extent foreign to the locality, and has sprung up there since the beginning of the war’; by early 1917 it was ‘a hot-bed of immorality, undisguised and unchecked’, where ‘Prostitutes of all types and ages, but noticeably in most cases young and rather showily dressed, parade the streets and loiter at the corners….’ Around this new local trade ‘convenient “lodgings” abound in every direction’ and public houses happily tolerated the women and their clients.

In the West End, in Soho and Fitzrovia, streets long used by prostitutes continued to hold their own. In March 1916 Arnold Bennett dined at the Reform Club alone and wandered into the West End: ‘London very wet and dark and many grues [eerie apparitions] mysteriously looming out at you in Coventry Street.’ In June 1917 he strolled out again: ‘Walking about these streets about 10 to 10.30 when dusk is nearly over, is a notable sensation; especially through Soho, with little cafés and co-op clubs and women and girls at shop doors. It is the heat that makes these things fine.’ And perhaps the war-enforced darkness too: as on ‘the north side of Coventry Street, where officers, soldiers, civilians, police and courtesans marched eternally to and fro, peering at one another in the thick gloom that, except in the immediate region of a lamp, put all girls, the young and the ageing, the pretty and the ugly, the good-natured and the grasping, on a sinister enticing equality.’

Although there were very large numbers of men in London in these years, it is impossible to determine whether the numbers of prostitutes on the streets rose in proportion. What figures we have are for arrests and convictions for soliciting and associated offences, and these are likely only to have affected the full-time professional prostitute. Both declined significantly during the war years, arrests falling from 9,406 in the two years 1913-14 to 5,843 in 1917-18, despite the public furore over prostitution rising to a fever in 1917 and despite the operational strength of the Metropolitan Police rising by 10 per cent or so over the course of the war. Although the police had many new wartime obligations that must have squeezed out routine duties these figures hardly suggest any rise in full-time professional street prostitution of the traditional London kind. Similarly, convictions for brothel-keeping fell away from an average of 249 a year over the five years before the war to 191 in 1914-18.

Nor does there seem to be much evidence for a rise in the numbers of foreign prostitutes on the streets of London, though they were frequently complained about at the time. Known German prostitutes were removed under the restrictions imposed on enemy aliens at the outset of the war, though it is likely the place of some would have been taken by French and Belgian women. When Belgian and other continental entrepreneurs moved into the old German quarter north of Oxford Street, taking over abandoned cafés and restaurants and starting up new ones, continental freedoms allowing prostitutes the free run of their places quickly brought them trouble from the police. ‘I beg to report’, the Sub-Divisional Inspector at Tottenham Court Road police station wrote to the Commissioner in November 1916,

that a large number of Cafe’s [sic] kept by foreigners have sprung up on this Sub-Division during the past few months and I have received information that drink is sold in several of them, and that gaming is also carried on. Disorderly conduct is prevalent, prostitutes and other undesirables are harboured, and the establishments are much frequented by British, Colonial, and foreign soldiers. Most have Automatic Pianos which are playing almost continuously till late at night.

Of 28 places listed, 22 were said to be used by prostitutes, their proprietors Belgians, French, Swiss, Russians and Romanians. Prosecutions for harbouring prostitutes were duly brought against the Café d’Alliés in Rathbone Place, the Au Roi Albert Café in Tottenham Street, and the Café Franco-Italian in Windmill Street, the last two (run by a Belgian and a Frenchman respectively) described as brothels. Reports of foreign-run brothels appeared frequently too in the London press, as indeed did the homegrown variety, run by women and men alike throughout St Pancras, Holborn, Westminster and Marylebone. Even so, not all the prostitutes using these places can have been foreigners even where the proprietors were: the police at Bow Street, for instance, charged 211 ‘known prostitutes’ with soliciting and similar offences during 1916 – one was Belgian, one Danish and 209 were British.

In all the excitement of the times maybe it was the girls and women ‘out for a lark’, or ‘amateurs’ over whom ‘the police have no control’, who were the dominant figures in London’s lively street life, and who also benefited in the trade in casually-rented cheap lodgings around the railway stations in particular. We might get closer to this reality by looking in more detail at the district around Waterloo Station.

No area drew greater press interest or produced more sensational rumours than this congested district of north Lambeth. Its notoriety as a place of prostitution in London went back generations, even predating the railway station, but the trade was greatly extended when the terminus of the London and South Western Railway and other companies was planted there from 1848. Waterloo Station’s rebuilding was begun in 1909 but delayed by the war and not completed till 1922. Even so, as the main terminus for Southampton and Portsmouth, the station handled trains carrying hundreds of thousands of soldiers and sailors on leave or injured. The station’s connection with the armed services in fact went deeper. The largest military hospital in the country, King George’s, opened in June 1915 in Stamford Street, occupying what was formerly the huge HMSO and Office of Works Store; from here walking wounded in their ‘hospital blues’ would take the air and meet comrades at Waterloo Station. And there was an earlier famous connection in the Union Jack Club, a great club house with restaurant, billiards room and hostel accommodating 335 men for a night or two and opened in Waterloo Road in July 1907. The Union Jack Club cemented the district’s connection with prostitution too: for servicemen and no doubt others, the area around Waterloo Station was known as ‘Whoreterloo’.

It was this unlovely London neighbourhood that encapsulated in a few streets the anxiety of the nation, even the Empire, over the sexual morality of its servicemen during wartime. It is possible, with caution, to pick out some of the reality of ‘prostitution’ in its various forms from the sensationalism that began to paint the district in such lurid colours during the winter of 1916–17.

First, the numbers. They seem to have been generally very large. In 1915 ‘upwards of 800 women were charged’ at Kennington Road police station ‘for offences of indecency soliciting &c.’, mainly in Waterloo Road and around. This seems to have continued throughout the war. ‘Night after night the short stretch of road between Stamford-street and the “Old Vic. [theatre]” is thronged by women who are unmistakeably pursuing the traffic of prostitution’, it was said in February 1917: ‘The whole district is so infested by prostitutes that no one could walk a hundred yards from the station in any direction without passing scores of them.’

The ages of women prosecuted ranged generally from 18 to 25 but with a minority of older women in their forties. By no means all of the young women were ‘common prostitutes’ known to the police. ‘Two, who said they were only “larking”, were remanded for inquiries; a third, who said she was going to be married next week to an Australian soldier, was also remanded’. And ‘Ann Newman (25), milliner, took a soldier by the arm and invited him to go for a walk with her. She had been in regular work for 11 years. – The magistrate remarked that she was beginning to play the fool with soldiers and bound her over to be of good behaviour.’ ‘Playing the fool’, ‘having a lark’, all laid women open to arrest, a night in the cells, a lecture by the magistrate and their names in the papers, although some women were indeed looking for a treat and a payment for their time: ‘Alice Brown (43), independent, and Nellie Taylor (36), no occupation, were walking arm-in-arm and stopping soldiers. Brown was overheard to say to one “Are you coming for a walk with us, dear?” They were each ordered to find a surety in £5 to keep the peace, or to undergo six weeks’ imprisonment.’ Among many hundreds of the more professional sort we might cite Jessie Tate, 24, of Tenison Street, leading ‘an immoral life’ for two years and just out of prison; or a girl of 19, formerly in domestic service at Bath, who told the magistrate ‘she “was prepared to go to the devil her own way”’; or one Madge Thatcher, 21, no fixed abode, fined 30s for soliciting in Waterloo Road or 21 days’ imprisonment.

In and around this thriving trade a distinctive housing market had been constructed for generations. Some were ‘brothels’ where more than one prostitute lodged, perhaps complete with maids and ‘bullies’ to protect them. More were ‘disorderly houses’ where prostitutes could take a client for a ‘short time’ or longer. This housing market was likely to have been extended in every direction during the war. There was a hierarchy that rested on some private nuance of respectability: ‘”we never take ins and outs”’, a 58-year-old packer explained to the magistrate of the disorderly house run by himself and his wife at 85 York Road in early 1917: ‘“They must stay the night.”’ For the ins and outs the profits were potentially very large. Maud Yates, 43, was said to receive 8s 6d for every man taken to her house in Brook Street, Newington, where two prostitutes lodged, for instance. Of whatever variety, houses like this were all over the Waterloo Road district and leached out in all directions. The trade was so profitable that many took advantage of this special housing market by letting prostitutes use their premises, at a price: a dentist in Waterloo Road, secondhand furniture dealers in Lambeth Walk, music hall artistes finding a lucrative sideline for a flat in Cranworth Gardens, Brixton; and it attracted women and men of all ages and conditions, like Sarah McGann, 80 years old, convicted of running a disorderly house in Chichesley Street, York Road, and fined £10: ‘“I’ll lose my Lambeth and old age pensions and have to go into the workhouse”.’ Or Emily Woolougham, 81, fined £15 for running a disorderly house at Kennington Park Road; she paid by cheque, confessing to a private income: ‘Well-to-do Octogenarian Brothel-keeper’ was the headline in the local paper.

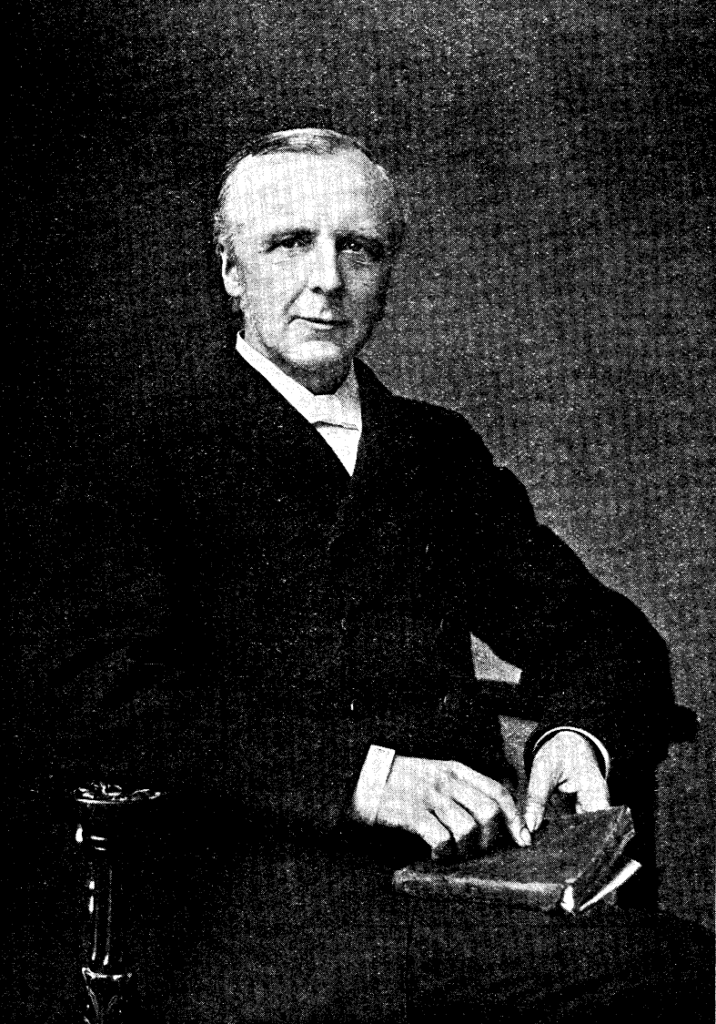

Inevitably this was a trade whose pleasures could not fail to arouse the prurient and the prudish. The most sensational claim made against London prostitution in general and the Waterloo Road district in particular was that women were drugging soldiers and then robbing them of everything they had, including their virtue. It was the Rev. Frederick Brotherton Meyer, Baptist minister of Christ Church, Westminster Bridge Road, a tireless self-publicist, who first publicly made the claim to the Surrey licensing bench at Southwark Town Hall in February 1916. He told the magistrates, ‘I have met with many cases of men who have been drugged and who have been at the mercy of any harpy who desired to plunder them.’ Soldiers, especially colonials from Australia and Canada, had lost not just substantial sums of back-pay, ‘but they lost more than that. They lost self-respect and purity, and those great thoughts of London which had brought them there.’ ‘Dr. F.B. Meyer’s Startling Statements’ were immediately picked up by the press. His supporters among local evangelicals were quick to bring forward ‘proof’ that individual soldiers known to them had indeed been drugged. But when the police asked Meyer for details of any cases, none of which had he brought to their attention before making his public statements, they all proved too vague and insubstantial to be investigated. The police thought the men referred to were merely drunk, sometimes on home-distilled alcohol or ‘Pot Sheen’ [poteen], sold to them in backstreet shebeens.

It was around this time that the state of the streets near Waterloo Station became a national scandal, taken up by the daily press and leading to official protests from Dominion representatives over the risks posed to their young men on the streets of London. Cases of robbery and assault on colonial troops, better paid than homegrown Tommies, were given special prominence in the newspapers and there seems little doubt that some among the residents of this notoriously tough district saw these colonial men as easy pickings. So we read of two women and a man imprisoned with hard labour for robbing an Australian convalescent soldier whom one of the women met in Waterloo Road. Two young women, 19 and 24, were given hard labour for robbing a soldier of the Canadian Mounted Rifles of £8 in a pub in Waterloo Road – it was his first visit to London. And a 38-year-old cook was imprisoned for stealing £13 from an Australian soldier she had met in Waterloo Road; there were numerous others.

Things might get more serious. On 8 November 1917, Private Oliver Imlay, a Canadian soldier, met a comrade at the Waterloo YMCA Hut. Out for a stroll they got chatting to two Australian soldiers who were with some girls. The four men decided to go in search of a drink and fell in with a local dock labourer, Joseph Jones, who promised to get them some ‘whiskey’. In a dark passage, Valentine Place off Blackfriars Road, both Canadians were hit over the head, probably with truncheons and probably by Jones and one of the Australians. The Canadians were robbed as they lay in the street. Imlay’s skull was stoved in and he never recovered consciousness. All three stood trial for murder and Jones was hanged at Wandsworth gaol in February 1918.

Women were in even greater danger during these murky transactions. In February 1915 Alice Jarman, about 40, a prostitute then living in a woman’s common lodging house in Crescent Street, Notting Dale, one of the poorest and roughest districts of London, was found dead in a ditch in Hyde Park. ‘There was a terrible gash in her throat, and wounds in her abdomen, arm, and chest,’ apparently inflicted with a bayonet. She had last been seen in the company of a soldier in the Uxbridge Road. Despite ‘an old sword-bayonet in [a] scabbard’ being found in a sewer nearby, and despite 900 troops put on identity parade at White City barracks, Jarman’s killer was never found.

Amid all the talk of a ‘“harlot-haunted” London’ it is difficult to look behind the sensationalising of wartime prostitution and uncover what it might have meant for those involved at the time. We come closest to the yearning and pity of it all from the rich observations of Sylvia Pankhurst, who visited Waterloo Road with some companions during the height of its scandalous notoriety one biting-cold Saturday night. She crossed over Waterloo Bridge from the north.

In one of the alcoves of the bridge sat a merry party – two sailors and two women – opening packets of sandwiches and cake, with quip and joke. In another a man and woman were together silent, hand clasping hand, in the moveless throes of sorrow.

Over the bridge the people were denser; policemen and special constables met one almost at every step. Sometimes a woman stood by the curb, or hung back close to the wall. Just as one chose, one could deem her a “harpy,” or merely a respectable woman waiting for a ’bus or a friend. Two soldiers went by us together, and behind them two girls, giggling noisily – to attract the attention of the men, one might judge if one pleased, or just with the jolly unconsciousness of youth, enjoying its night out.

The ‘orgy of licentiousness’ said to have been brought on by war elicited an immediate response among guardians of the Londoners’ morals. One long-lasting consequence was in the creation of an entirely new extension of London’s policing arrangements. This was the first appearance of a women’s police force. Their presence was felt most in London’s streets and parks. Their object was to deter or disrupt immoral behaviour rather than crime prevention. Just what constituted behaviour worthy of intervention was very much in the eye of the beholder. The women police usually patrolled in pairs and, in troublesome districts with large numbers of professional prostitutes likely to resent intrusion as in Waterloo Road, they were often accompanied by a police constable. In general, though, they left prostitutes alone. Their target was more the larking girls of the amateur variety, their purpose to discourage promiscuous mixing of the sexes, their tactics unsubtle and no doubt found objectionable by many. Mary Allen of the Women’s Police Service recalled with satisfaction how ‘The number of loiterers around Edgware Road and Marble Arch (often middle-aged well-dressed men) was considerably reduced. Finding themselves watched at every turn by policewomen, they would soon tire and move off.’ We get a closer look at their methods on the ground from the police at Vine Street, C Division:

They usually patrol in Piccadilly Circus, Coventry Street, Leicester Square, and Charing Cross Road, between the hours of eight pm and twelve-thirty am. They work in double patrols and appear to have a superior patrolling officer who has been seen to visit them from time to time.

On seeing a woman who probably appears to them to be a loose character they follow her a few yards behind, and if she stops and speaks to any other person, whether male or female, they sidle themselves as near as possible apparently to overhear any conversation that passes, and by their ostentatious action and persistent gaze compel the parties to occasionally separate or move away.

Unsurprisingly, there were complaints: of the Women Patrols ‘flashing electric torches in the faces of respectable persons sitting on the seats in Hyde Park after dark’, for instance; and a ‘lady’ in Wimbledon complained to a magistrate that two of the WPS had told her 14-year-old daughter that ‘she “ought not to crimp her hair and must put her hat on straight”; also that she was “dressing herself up and walking about to attract the attention of men.”’

It was around 1917 that the question of prostitution in London generated something like a national panic, this time over its role in spreading venereal disease. The temperature was raised by colonial politicians in London for the Imperial Conferences held in London in 1917 and 1918. Some used ‘very strong language’, Sir Robert Borden, the Canadian premier, publicly stating ‘that in no further war would he or any Prime Minister of Canada allow any troops to come to this country, because of the dangers which lie before them and the reckless disregard of the health of the troops.’ It was not the dangers of the trenches he had in mind but the ‘women on the London streets [who] are the real cause of the downfall of their men.’

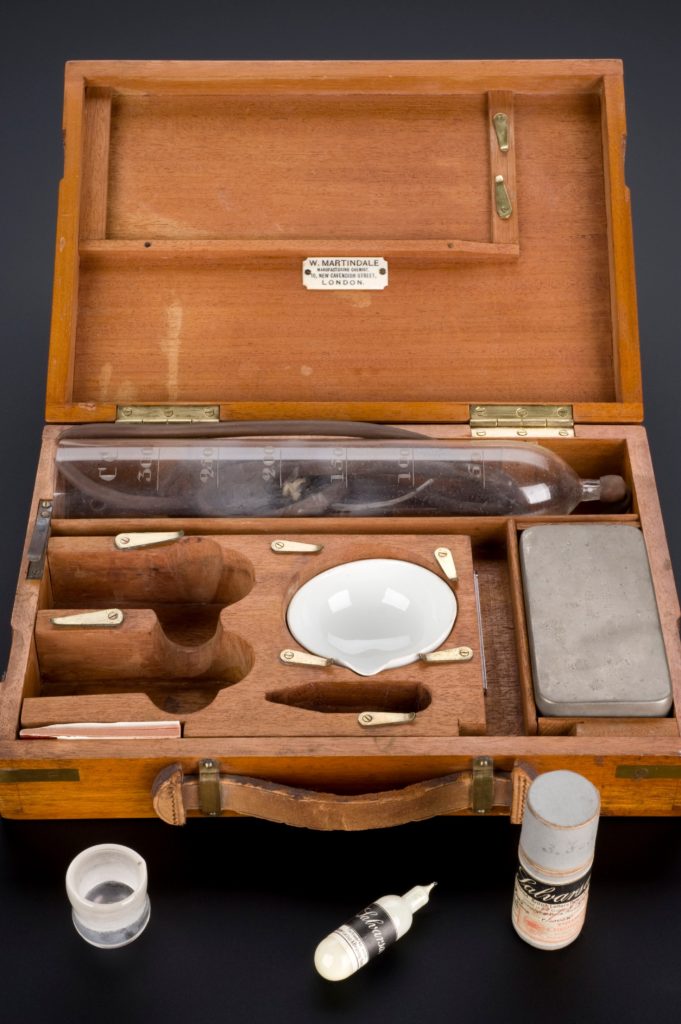

The official reluctance to push prevention through the use of condoms and post-coital treatments – thought to be a threat to the nation’s morals – left the suppression of prostitution and punishment of individual prostitutes as the only acceptable policy available, together with improved treatment of those who had already caught the disease. This last had been made easier from 1913 by the development of an effective treatment for syphilis, the arsenical compound ‘salvarsan’ or ‘606’; unfortunately it was discovered by Dr Paul Ehrlich, a German Jew, and its manufacture was in enemy hands until alternative supplies could be generated in Britain and France a year or so after the outbreak of war.

A Royal Commission on Venereal Diseases had been set up immediately after Ehrlich announced his discovery to the world at an international medical congress held in London; it reported finally in 1916 and among many recommendations proposed that salvarsan be made freely available to sufferers through local authority clinics, which should also take on health propaganda to warn of the dangers of contracting VD. The means to avoid catching the disease, however, were ducked, the Royal Commission relying on ‘more careful instruction in regard to self control generally, and to moral conduct as bearing upon normal relations….’

Others though held to a more robust approach, advocating greater, even draconian, control over women as the main source of infection and demoralisation. FB Meyer in early 1917 called for young women found ‘interfering with soldiers’ in the streets to be ‘shut … up to work in munition factories’; and Arthur Conan Doyle pressed the government to take severe action ‘to hold in check the vile women who prey upon and poison our soldiers in London’:

These women are the enemy of the country. They should be treated as such. A short Bill should be passed empowering the police to intern all notorious prostitutes in the whole country, together with brothel keepers, until six months after the end of the war. All women found to be dangerous should be sent to join them. They should be given useful national work to do, well paid, kindly treated, but subjected to firm discipline at the hands of a female staff.

Government did not go this far. But a week or so later in February 1917 it sought to increase penalties for keeping disorderly houses and soliciting and proposed to make it a criminal offence for anyone infected with VD to have sexual intercourse. This last proposal was said in the House of Commons to have provoked fury among ‘All the women of the country’, with its suggestion of resurrecting the old Contagious Diseases Acts that had allowed the state to compel the intimate examination of women’s bodies, and had seemed to treat women so much less favourably than men.

While the Criminal Law Amendment Bill was being considered in the Commons some magistrates in London, caught up in the hysteria of the time, began to take the law into their own hands. In April 1917 magistrates at Brentford remanded to Holloway Prison two women charged with soliciting to ascertain whether they were suffering from VD – the hospital’s male doctor duly examined them, claiming they had raised no objection, and when found free from infection the magistrates acquitted them. The case raised a storm and generated anxious questioning of the bench by the Home Office. It was not the only case: in December a stipendiary magistrate at Westminster allegedly ‘sentenced’ a girl to the infirmary ‘“until cured”’; Cissie Green, 17, refused to have a medical examination until her mother said she would take her home if she was found not to be infected.

The Criminal Law Amendment Bill stalled, but the idea of a more restricted power to control women who might infect servicemen with VD took root. The use of DORA to protect soldiers against women began to be urged from late 1917, the pacifist leader Ramsay MacDonald one keen advocate among many. And we see something of the popular hostility to women over this issue in two cases arising at the turn of the year.

In early January 1918 police were called to a second floor back room in Great College Street, Camden Town, where they found Gladys Canham dead in bed. She had been shot with his service revolver by her husband, Private Henry Canham of the Machine Gun Corps. Gladys had deserted Henry and their baby and set up as a prostitute. When he returned on Christmas leave she had telegrammed him to press for a reconciliation and they spent the night together. While in bed she allegedly told Henry she had contracted venereal disease, she thought from an officer, and Henry shot her: ‘“I consider I only did my duty as I did in France,”’ he told police. Others thought he had done his duty too. At the trial at the Old Bailey the Crown accepted his plea of manslaughter and the Judge bound him over to keep the peace for two years in the sum of £5. Whatever the truth of the matter, Canham was examined and found not to be suffering from ‘the horrible disease’.

That same January, Phyllis Earl, ‘an unfortunate’ with three children and a husband in France, was found dead under a railway arch in Hackney Downs with her throat cut. George Harman, a local man who had migrated to Canada and was now a private in the Canadian Corps, admitted to murdering her but claimed in his defence she had infected him with VD: she had indeed been infected about a week before her death, according to Bernard Spilsbury, the Home Office pathologist. Harman was sentenced to hang, though the jury recommended mercy. A large petition was gathered in Harman’s favour and he was reprieved in March 1918.

That same month DORA Regulation 40D made it an offence for a woman with VD to solicit or have sex with a member of the armed forces. It was not an offence for an infected soldier to have sex with a woman, though it had been a disciplinary offence since 1889 to conceal VD. In the unlikely event of a woman complaining to a soldier’s commanding officer that she had been infected the soldier would be examined and court-martialled if appropriate. Regulation 40D quickly became notorious. A woman could not in theory be examined against her will but an examination was frequently the price of freedom, women being remanded to Holloway where in most cases an examination was submitted to. This unequal and intrusive treatment of women, turning the clock back to the 1880s, provoked much resentment nationwide. Petitions calling for the repeal of 40D were gathered from June 1918 with more than 600 of them by the end of October. But the regulation survived the Armistice and over a hundred women were convicted under it before the end of the war. Among all this high anxiety, one fact seems to have escaped attention: that despite some 400,000 British troops estimated to have contracted VD at home and abroad at some time during the war, the percentage of soldiers infected was lower than at any time since 1866, when figures were first collected; and lower than among the civilian population as a whole.

In all this then it is hard indeed to determine the reality of London life during the war compared to the contemporary picture amounting to a widespread ‘moral panic’. Did prostitution increase? The figures of arrests and prosecutions for soliciting or brothel-keeping indicate not, while the newspapers were full of what cases there were. Did public displays of sexual behaviour deteriorate? What we know of the behaviour of prostitutes in late-Victorian and turn-of-the-century London makes that difficult to believe, but all observers said it had. Was venereal disease a problem in the army? It undoubtedly was, but proportionately the cases were fewer than at any time since figures began, and the head-in-the-sand approach of the military and civilian authorities to education and distribution of prophylactics made a difficult situation far worse.

In so many ways, though no one knew it at the time, London’s home front of 1914–18 was but a dry run for the far more deadly civilian challenges of just 20 or so years later. All these difficulties would once again be raised in the Second World War, but with one difference I think: the moral anxieties of 1939–45 would not reach the pitch of hysteria that accompanied the question of ‘soldiers and sex’ in London during the Great War.

Note

£1 in 1915 had the approximate purchasing power of £60 in 2019. Source: National Archives.