War hero, trick-rider, entrepreneur with a flair for PR, the Lambeth-based Philip Astley was all of these things and more.

Jonathan Tyers put Vauxhall on the map when, between 1729 and 1750 he made Vauxhall Gardens the world’s most famous open-air resort. Astley (1742–1814) is the father of the modern circus. He began giving equestrian trick-riding shows at Ha’penny Hatch field in Lambeth Marsh in 1768.

In about 1769 Astley opened what is claimed to be the first modern circus, ‘Astley’s Amphitheatre’, at the Lambeth foot of Westminster Bridge. The showman interspersed his own daring feats of horsemanship with clowns, jugglers and tight-rope walkers.

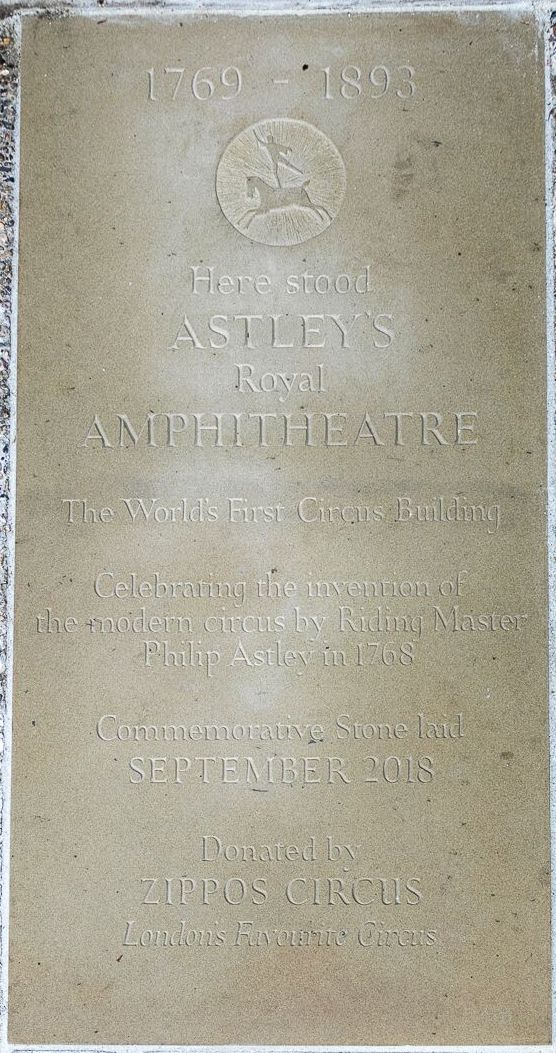

Astley’s Amphitheatre commemorative flagstone inaugurated at St Thomas’s Hospital on 14 September 2018. Photo credit: Cathy Cooper.

Astley’s whole life was an adventure. The foghorn-voiced Philip was born in Newcastle-Under-Lyme, Staffordshire, and apprenticed to his father Edward, a cabinet-maker with a passion for horses. The family moved to Lambeth two or three years later where, some sources say, Edward opened a shop near Westminster Bridge – an area to which the adult Philip would will later return – but Philip fell out with his father and in 1759, aged 17, enlisted in a cavalry unit, Colonel Eliott’s Light Dragoons. Six feet (183cm) tall at a time when the average recruit was 5ft 8in (173cm), he would have stood out from his comrades, even if he had not shown himself to be a fearless natural horseman.

Soon promoted to corporal, Astley became the 15th’s horsebreaker. In 1760 he and the 15th took ship for Bremen to fight alongside the armies of Frederick II of Prussia against the French in the Seven Years War (1756–63). Corporal Astley soon distinguished himself by rescuing a horse that was drowning in the sea, for which he was again promoted. He was wounded twice in battle, retrieved the regimental colours from the enemy at Emsdorf (despite being unhorsed and wounded), which he later presented to George III at a review in Hyde Park) and helped rescue of the Hereditary Prince of Brunswick at the Battle of Nauheim (1762) when he was surrounded by French Hussars.

Philip Astley after an unknown artist. Etching, early 19th century. NPG D9009 © National Portrait Gallery, London.

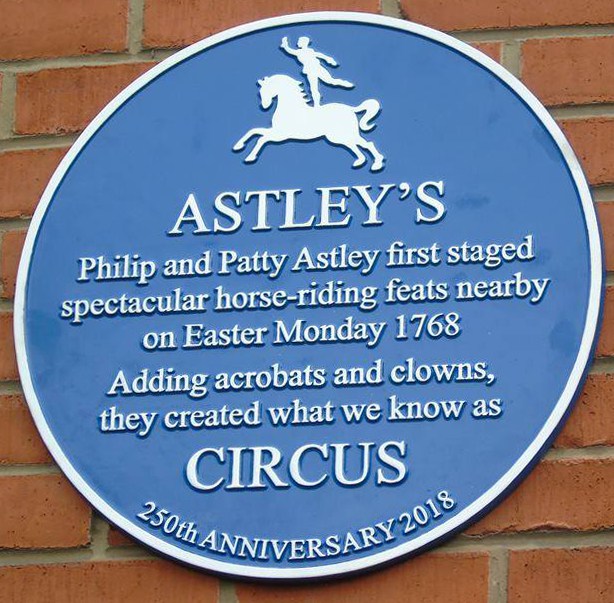

In 1766, having been made Serjeant Major of Horse, the highest possible rank for a non-commissioned officer, Astley was looking for change. He had made a significant social step up by marrying Martha (known as Patty or Petsy) Jones, a granddaughter of Sir Thomas Longueville, the 4th Baronet of Wolverton, the previous year. He decided to leave the 15th and within two years, he and Patty, who was a talented rider herself, were giving shows in a field known as Ha’penny Hatch. Astley rode three horses at a time, picked up handkerchiefs from the floor while cantering and did handstands in the saddle. Roupell Street and Cornwall Road, Waterloo are built on what was Ha’penny Hatch.

A plaque in Cornwall Road, SE1, near the site of Astley’s premises at Ha’penny Hatch, was laid 250 years after his first performance. Photo credit: LERA.

On 14 September 2018, the founder and director of Zippo’s Circus Martin ‘Zippo’ Burton (second from right, at back) brought a group of his performers to the site of the main entrance to Astley’s Amphitheatre, now the garden of St Thomas’s Hospital to unveil a commemorative flagstone. They included Cossack rider Tamik Khadikov, with his wife Helena; ringmaster Norman Barrett MBE; musical clowns Totti and Charlotte Alexis and their sons Charlie and Maxim; aerialists Vickki and Pablo Garcia and their sons Antonio and Connor; hand-balancer Melissa; and clown Paulo Dos Santos. Also present in authentic period costume to represent Mr Astley was actor, ringmaster and circus historian Chris Barltrop. Photo credit: Cathy Cooper.

Astley himself was always the main feature of the shows, but his decision to mix his manly feats of bravery on horseback with other forms of entertainment, including dramatic routines featuring Billy the Little Learned Horse, who was trained to play dead, and slapstick turns such as The Tailor Riding to Brentford in which Astley acted the role of an inept horseman, was inspired.

Advertisement for Astley’s British Riding School.

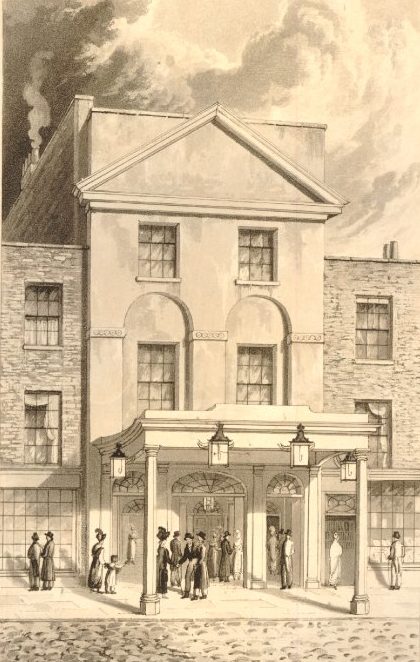

Success brought expansion, and in 1769 Astley bought a timber yard near Westminster Bridge, converting it into bespoke premises for his British Riding School, where he offered lessons in equestrianism during the day and shows in the evening. The ring was open to the elements but the audience, either sitting or standing, were under shelter so that the show could go on in the event of light rain. Astley now expanded the repertoire, adding a clown, acrobats, a strongman, monkeys and other equestrian performers. At first, the idea was to keep the audience’s attention between the equestrian acts, but eventually ‘variety’ became integral to the show.

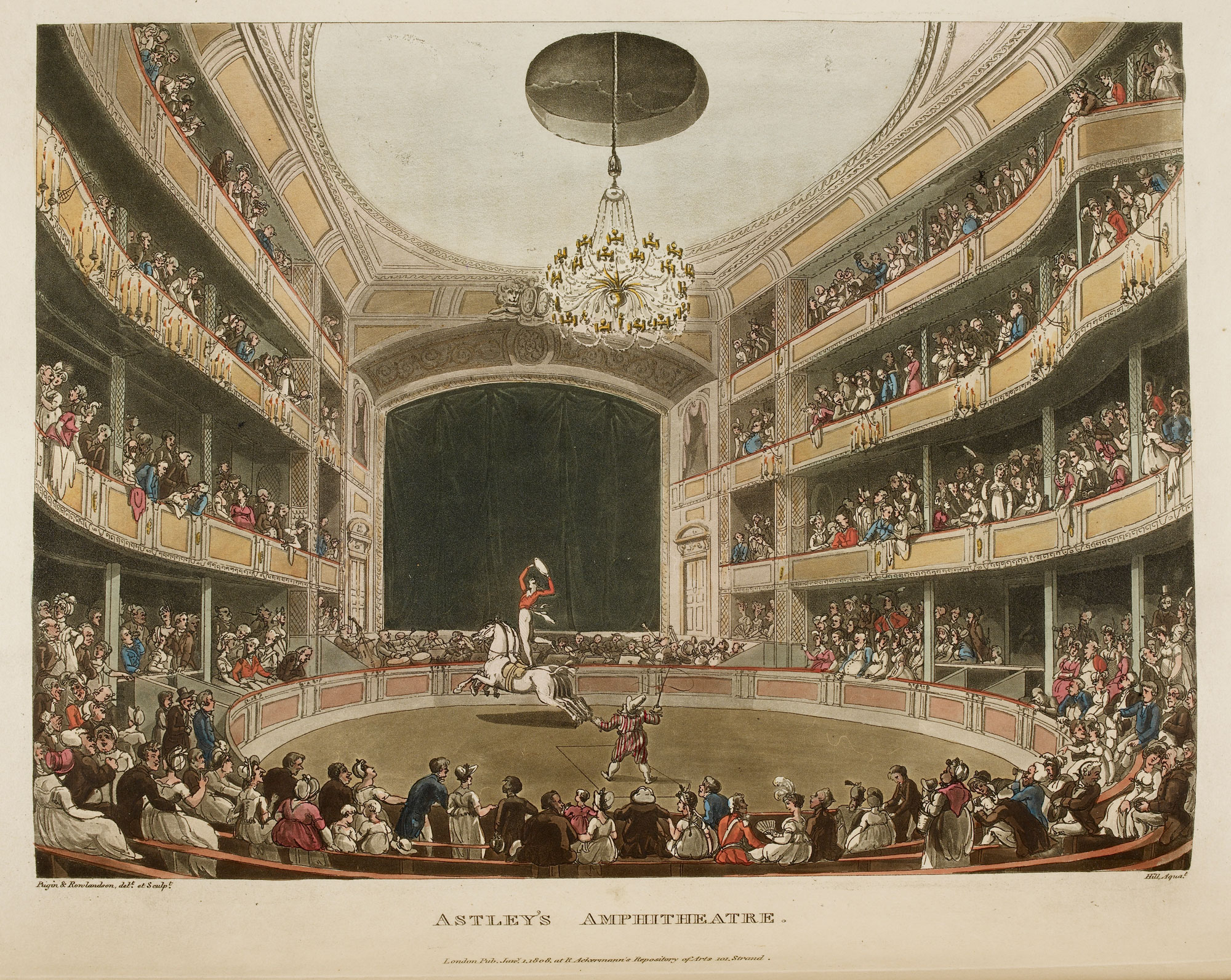

Astley’s main achievement, however, was the understanding that a circular ring rather than a rectangular arena not only allowed the audience a better view of the show and assisted in the ‘flow’ of the acts, but also made room for a larger audience. He also discovered that the centrifugal force generated when riding in the circle aided balance while riding. By experiment, Astley established that the optimum diameter for the ring was 42 feet (just under 13 metres).

Exterior of Astley’s Riding School, later Astley’s Amphitheatre, Westminster Bridge Road. Pencil and watercolour by William Capon (1757-1827). @ Victoria & Albert Museum.

George III commanded two performances and Louis XVI asked him to perform for him and his family at Fontainebleau. The Astleys also went on tour, frequently taking the show across England, Scotland and Ireland. In 1783 they set up the Amphithéâtre Anglais at the Rue Du Faubourg du Temple in Paris, which played to packed houses and they also established an amphitheatre in Dublin. Fireworks and balloons were incorporated into the acts.

Interior of Astley’s Riding School, later Astley’s Amphitheatre, Westminster Bridge Road. Pencil and watercolour by William Capon (1757-1827). @ Victoria & Albert Museum.

The French Revolution of 1789 put a stop to performances in Paris, but inspired Astley’s presentation ‘Paris in Uproar’ in which he re-enacted the storming of the Bastille. In fact, Astley’s Amphitheatre became famous for its re-enactments of battles, which were often accompanied by explosions and sound effects. Such scenarios, which later included The Fatal Bridge (1810); Battle of Waterloo (1824), Buonaparte’s Invasion of Russia, and the Conflagration of Moscow (1825) were hugely popular with audiences well after Astley’s death and into the Victorian era. The nearby Vauxhall Gardens took to mounting similar and even more ambitious re-enactments.

Astley’s Amphitheatre in London circa 1808. Auguste Pugin and Thomas Rowlandson, from Microcosm of London. Courtesy of Houghton Library.

By the 1790s Britain was again at war with France, and Astley, now pushing 50, re-enlisted in his old regiment. He was away on military service when in 1794 the amphitheatre burned down (it reopened in April the following year). The new building was horseshoe-shaped rather than circular, with a large stage with a proscenium arch. The two were interlinked by ramps so that the horses could run on to the stage from the ring. This ingenious design increased the scope for tricks and dramatic effects. Eight years later, in 1803, the Amphitheatre was once more destroyed by fire and again rebuilt.

Increasingly, the bill included comic musicals, dances and pantomimes, demonstrating that Astley was competing not only with his circus rivals (Charles Dibdin’s Royal Circus was at the southern end of Blackfriars Bridge) but with conventional theatres as well.

Astley’s Amphitheatre, 1819, drawn and engraved by Daniel Havel. Copyright: British Museum.

Philip Astley died in Paris aged 72 and was buried in the Père Lachaise cemetery. Andrew Ducrow, one of Astley’s riders, acquired the business, selling it in 1841 to William Batty after the building sustained its third fire. William Cooke leased the building from Batty and ran Astley’s until 1860. ‘Lord’ George Sanger bought it in 1871. The building was demolished in 1893 after falling into disrepair.

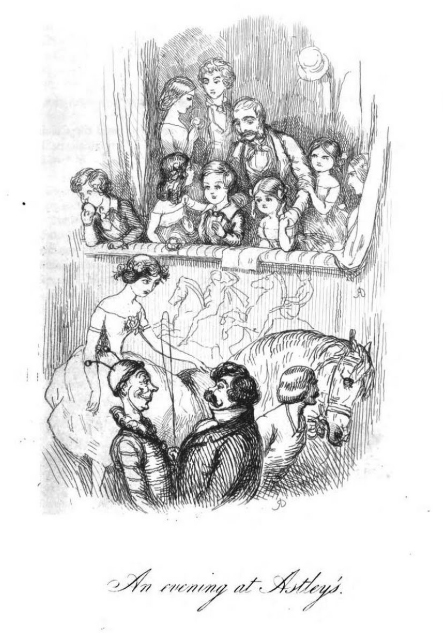

There are many references to Astley’s in literature: In Jane Austen’s Emma, a visit to Astley’s brings about the engagement of Robert Martin and Harriet Smith; Charles Dickens’s short story Astley’s appears in Sketches by Boz and Astley’s also makes an appearance in The Old Curiosity Shop and Hard Times. Astley’s also crops up in Thackeray’s The Newcomers.

More generally, Astley’s contribution to culture was enormous. His entertainments, a series of acts that combined risky and tense displays of skill with comic relief, have universal and continuing appeal.

An Evening at Astley’s from The Newcomes: Memoirs of a Most Respectable Family, Vol 1, by William Makepeace Thackeray.

Sources

Ward, Steve (2018). Father of the Modern Circus: ‘Billy Buttons’. Barnsley: Pen & Sword.

circopedia.org

With thanks also to Jon Newman, Manager of Lambeth Archives, and Chris Barltrop.