by VauxhallHistory.org online editor Naomi Clifford

Image © Naomi Clifford

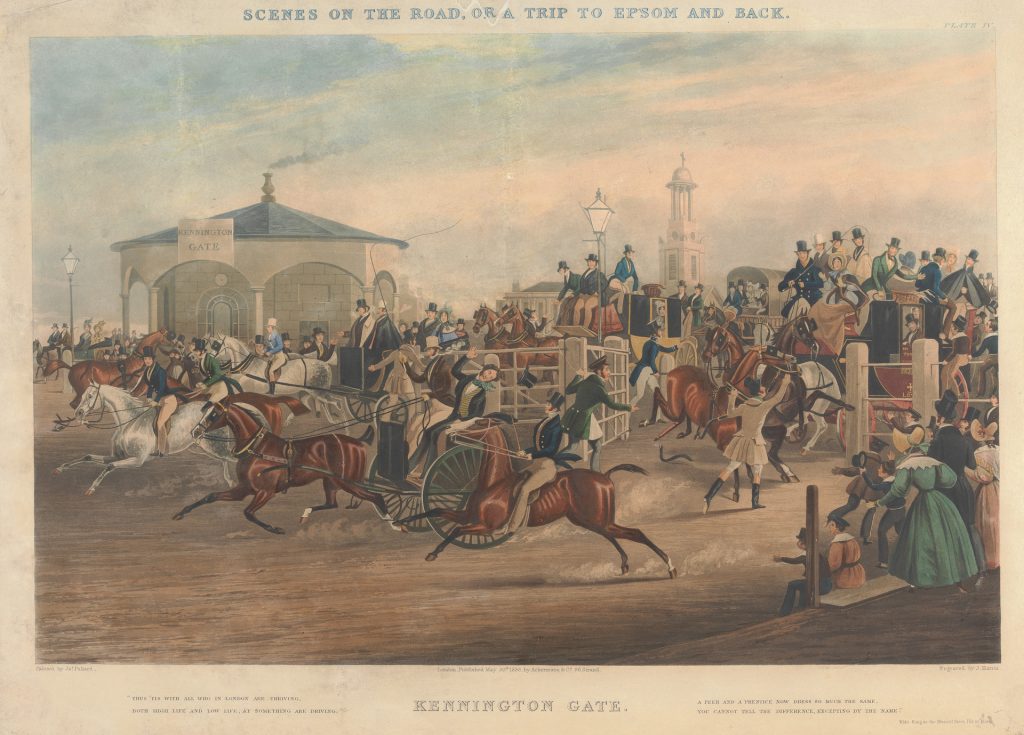

On his way to the gallows at Kennington Common,[1]The spot where St Mark’s Church now stands. Jeremiah Lewis Abershaw did what many a condemned felon had done before him: during the mile-long journey from Horsemonger Gaol in Newington to the gallows he played to the crowd. Abershaw travelled to his agonising death on Monday 3 August 1795 in the cart with two condemned murderers, one male and one female. [2]John Little, a quiet, apparently religious man, was a curator in the laboratory at Kew Observatory in the Old Deer Park at Richmond. A particular favourite of George III’s, he was in debt to an … Continue reading Abershaw’s friends, many of them fellow gang members, attended his hanging out of loyalty. The rest of the large crowd, most of them working poor, came to see the demise of a notorious rogue and to enjoy a day off work.

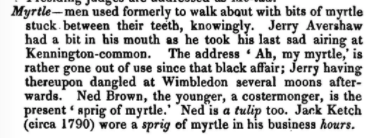

Jerry Abershaw was a known villain who had been found guilty of shooting at a police officer. There was a glamour about him similar to that which clung to Jack Sheppard, the notorious thief and gaolbreaker executed 71 years earlier. Both had the devil-may-care insouciance of youth – Abershaw was 24, Sheppard 22 when they were executed. On the day of his death Abershaw was on full tilt, sporting a sprig of myrtle out of the side of his mouth, his shirt artfully unbuttoned to the waist, and playing with his luxuriant dark curly locks. To his fans he was a Jack-the-lad who went even to his death thumbing his nose at the Establishment. The condemned man could do so only metaphorically, for his was pinioned – bound at the elbow – allowing him to raise his hands in prayer but not, in his last moments, to resist the hangman’s noose.

Until 1799 the county of Surrey used the horse-and-cart method of hanging. The condemned, noosed and hooded by the hangman, would stand on a cart. The rope was run over the gallows and attached to the horse which was then led away, leaving the victim to dangle and slowly choke to death. If not prevented by the Sheriff’s men, relatives and friends might rush forward to pull on his or her legs. This was meant as a kindness, to bring about a swifter end. In some cases supporters might want to fight over the deceased’s clothes, which were legally the property of the hangman.

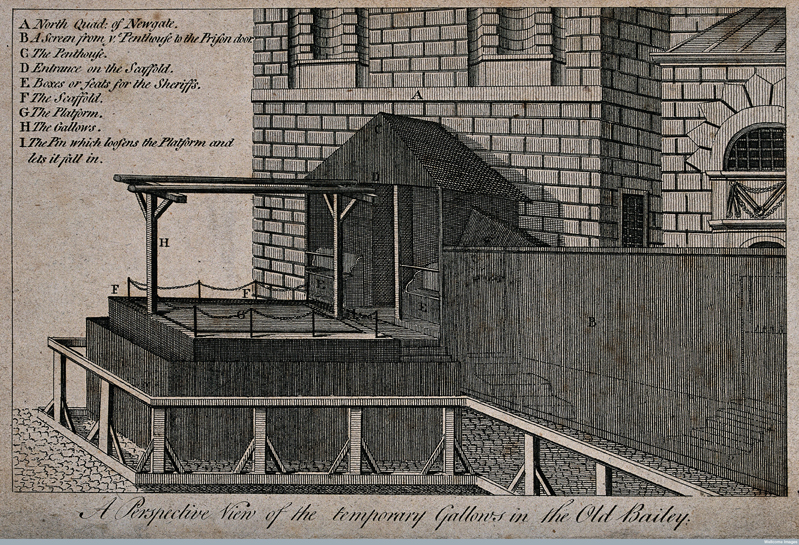

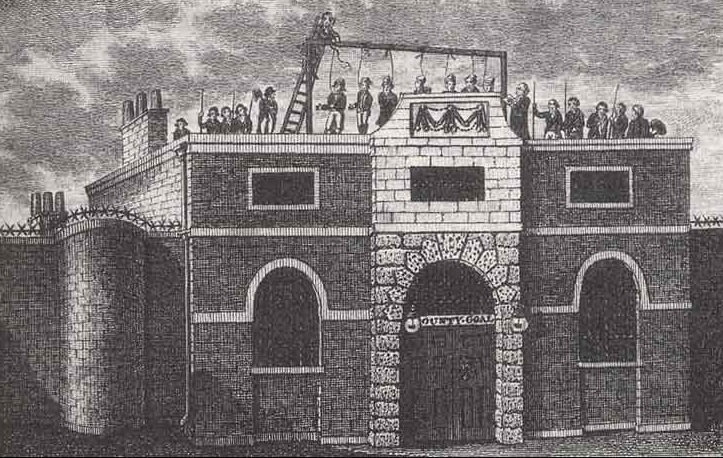

In 1800, five years after Abershaw’s dispatch, Surrey adopted the ‘New Drop’ method of hanging, already in use for the previous 17 years at Newgate Prison in the neighbouring county of Middlesex). Thenceforth, no carts trundled the condemned to Kennington, for all hangings took place on the roof of the Horsemonger Gaol. The switch was not made primarily for humane reasons. Too often, the final journeys of condemned felons were unseemly cavalcades of ribald, sweary mayhem at the end of which the condemned failed to confess or to exhort the crowd to avoid his or her mistakes or, worse still, proclaimed their innocence. Shock and awe was what the authorities wanted: justice administered solemnly but swiftly, a short, heartfelt confession, a brief religious ceremony and a brutal, frightening death.

The sudden throw of a lever, the drop and the convulsive death throes were meant to deliver an unforgettable message to the labouring poor: crime leads you to the gallows; don’t even consider it. In reality, everyone knew that the only crime certain to lead you to execution was murder. With all others, you had a sporting chance of imprisonment or transportation.

Abershaw, a brute “fierce, depraved, and infamous”, in the words of The Newgate Calendar, was what we would now recognise as a mobster, for he ran a network of “thieves and and imposters” committing highway robbery, housebreaking and other crimes in London and surrounding counties.

cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Des Blenkinsopp – geograph.org.uk/p/5072630

Born in Kingston-upon-Thames in or around 1773, Jerry Abershaw was seemingly not predestined for a life of crime. His parents were respectable, his father was a dyer at Bankside. As a teenager Abershaw himself had worked nearby, reputedly as a coach driver. But by the age of 17 he discovered that holding up post-chaises was more lucrative than driving them.

Not much is known about Abershaw’s exploits in the years between 1790 and his execution in 1795, although a few snippets survive. He was taken ill on the road and given a bed in a house in Putney, and a local surgeon, William Roots, sent for. Before Roots left, Abershaw warned him to be careful on his journey home. “You had better have someone to go back with you as it is a very dark and lonesome journey,” he said to which Roots remarked that even if he should meet the notorious Abershaw he would not be afraid.

Over 33 years after Abershaw’s death the Evening Standard noted the death of a veteran police constable who had been in the service at Worship Street for more than 50 years remembered encountering Abershaw, who only escaped from him by breaking through a lath and plaster partition and making his way over the roof.[3]21 November 1828, 4D.

According to the Newgate Calendar, as Abershaw awaited death in prison, he “painted” scenes from his life on the walls of the condemned cell using juice from a bunch of cherries. One picture showed Abershaw “running up to the horses’ heads of a post-chaise, presenting a pistol at the driver, with the words, “D—n your eyes, stop,” issuing out of his mouth; [in] another … he was firing into the chaise; [in] a third, … the parties had quitted the carriage; several, in which he was pourtrayed [sic] in the act of taking money from the passengers.”

The villain’s haunts, when not waylaying post-chaises, included the squalid slums of Saffron Hill (present-day Old Street, EC1)As for pubs, there was Green Man inn at Putney Heath and the Bald Faced Stag near Kingston and he numbered another infamous highwayman, “Galloping Dick” Ferguson.

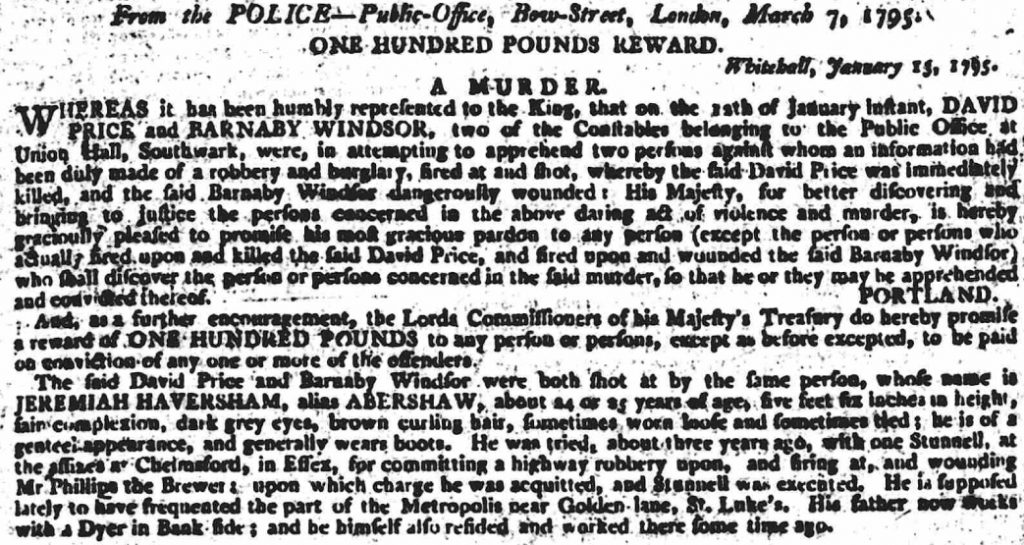

Eventually the law caught up with Jerry Abershaw. Three years before his appearance at Kennington, he was apprehended for non-fatal wounding of a Mr Phillips, a brewer. Abershaw was tried at Chelmsford in Essex, but acquitted. The authorities, however were determined to make an end of him. Abershaw was acquitted and Stunnell executed.[4]I can find no record of this. Stunnell may have been related to John Stunnell, who was executed at Tyburn in 1782 for abetting a murder during a highway robbery, but I cannot confirm this. Both The … Continue reading It cannot have been a surprise to Abershaw that the authorities were determined to make an end of him. In London, according to The Newgate Calendar, constables traced him to the Three Brewers in Tooley Street, and staked out this “resort of thieves and vagabonds.” Yet someone tipped off the fugitive and he was ready when they came for him. Standing in the door of the pub parlour, a pistol in each hand, Abershaw shot officers David Price and Barnaby Windsor, the former fatally.

Wanted-man advertisements soon in newspapers countrywide.[5]The Newcastle Courant, for example, in March 1795 carried a Hue and Cry notice (a process by which bystanders are summoned to assist in the apprehension of a criminal who has been witnessed in … Continue readingA £100 reward was offered for Abershaw’s apprehension. Felons shopping him were promised a pardon.

Abershaw’s trial before Mr Justice Perryn at the Surrey Assizes at Croydon was swift. His counsel tried to argue that somebody else could have fired the fatal shot but the jury took just three minutes to find the defendant guilty. The surviving constable, Barnaby Windsor, managed to give evidence despite the injury to his head. To the surprise of many and perhaps the disappointment of some, Abershaw was reasonably well behaved during the trial. He may have been elated when a flaw in the indictment was discovered which meant that there would have to be a re-trial. But the prosecution ended any hopes of escape by having him tried for the shooting of Barnaby Windsor. Found guilty, Abershaw resorted to his habitual jeering. As the judge, now wearing the black cap, passed sentence of death Abershaw slapped his own hat on his head in mimicry, pulled up his breeches and mocked the bench. The now-condemned man had to be bound hand and foot before being bundled, swearing, out of the dock.

Thousands turned out to witness Abershaw’s execution, sure he would put on a show. He did not disappoint. There was the rollicking cart journey, the foul language, the louche appearance, and at last, a defiant shedding of his footwear, apparently to disprove his mother’s prediction that he was a bad lad and would die with his boots on.

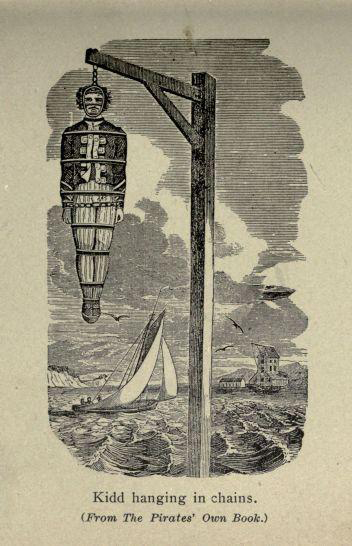

After the drop, the twisting and finally death, Abershaw’s body was taken to be hanged in chains at Putney Bottom near the scene of many of his crimes.[6] For years afterwards this area was known as Jerry’s Hill.. Only men’s bodies were subjected to this postmortem punishment, which was meant as a stark reminder to others to avoid copying the offender’s errors.[7]Gibbeted bodies were left on the gibbet for weeks and sometimes months. Abershaw’s gang members were not rattled, however. They scaled the gibbet to prise the bones out of his fingers and toes, apprently to use as stoppers for their pipes). Buttons were also snipped off the his coat as mementos. Relics from the bodies of executed criminals were believed to hold special powers, even to have beneficial medicinal effects.

Charles (1842), Pirates own book : or, Authentic narratives of the lives, exploits, and executions of the most celebrated sea robbers…, New York: A. & C. B. Edwards; Philadelphia: Thomas, Cowperthwait, & co.

Dismemberment and mouldering away on Jerry’s Hill was not quite the end for Abershaw, who lived on for half a century or so in popular culture. He “returned” to Lambeth in 1826 in “the popular Dramatic Sketch of Jerry Abbershaw, [sic] the Rum-Padder of 95” [8]Morning Advertiser, 26 January 1826, 2A. at the Royal Coburg Theatre, now known as the Old Vic, in Waterloo. His ghost appeared in The Haunted Inn at the Drury Lane Theatre in 1828.[9]Evening Standard, 1 February 1828, 3D. A racehorse was named after him[10]Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 25 February 1844, 3A, lists “Jerry Abershaw, by Jerry, 2 yrs,” trained at Epsom, Mickleham by W. Lumley for Mr Drinkald.

Mr Darville played the title role in Dirty Dick, or Jerry Abershaw the Highwayman at the Queen’s Theatre, Tottenham Street in 1842, with “a manly spirit and graceful recklessness” according to The Morning Post[11]29 March 1842, 3F Henry Downes Miles wrote a serialised novel, Jerry Abershaw, or the Mother’s Curse, published 1847–8, which was dramatised as The Life and Death of Jerry Abershaw: The Highwayman; or, A Mother’s Curse and played at, among other theatres, the Victoria in 1856. Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894) considered writing a story to be titled Jerry Abershaw: A Tale of Putney Heath but in the end did not.

Abershaw was not the very last of the highwaymen but he was the last to be well known. His friend “Galloping Dick” Ferguson was executed at Aylesbury in 1800 but he never commanded the same admiration as Abershaw. As for highway robbery, its decline can be traced to the Bank Restriction Act 1797. This was a government response to a panic over payments in gold at the banks. For the first time, banks were allowed to issue one- and two-pound notes and these could be more easily concealed from robbers than gold coins. If stolen, notes were difficult to exchange for cash as they were “promises to pay” and had to be signed. Next, the coming of the railways did away with the post-chaise and with it the likes of Jerry Abershaw.

Other executions at Kennington

Naomi Clifford’s latest book Women and the Gallows 1797–1837: Unfortunate Wretches is available from Pen & Sword. She looks at the stories of the 131 women who were hanged in England and Wales for crimes including murder, infanticide, theft, arson, sheep-stealing and passing forged bank notes.

References

| ↑1 | The spot where St Mark’s Church now stands. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | John Little, a quiet, apparently religious man, was a curator in the laboratory at Kew Observatory in the Old Deer Park at Richmond. A particular favourite of George III’s, he was in debt to an elderly gentleman called Mr McEvoy, who lived on the lane between Kew and Richmond. Lacking the means to repay McEvoy, Little broke into his creditor’s house at night and beat to death both McEvoy and his elderly housekeeper. He was soon caught. Little may also have been responsible for the murder of Mr Stroud whose body was found under an iron vice in the Octagon Room at Kew Observatory. Sarah King was executed for murdering her newborn baby son. Information from St Margaret’s Community Website. |

| ↑3 | 21 November 1828, 4D. |

| ↑4 | I can find no record of this. Stunnell may have been related to John Stunnell, who was executed at Tyburn in 1782 for abetting a murder during a highway robbery, but I cannot confirm this. Both The Newgate Calendar and a Hue and Cry notice published in newspapers, in March 1795 (for example, the Newcastle Courant) state that Abershaw and Stunnell were tried at Chelmsford. |

| ↑5 | The Newcastle Courant, for example, in March 1795 carried a Hue and Cry notice (a process by which bystanders are summoned to assist in the apprehension of a criminal who has been witnessed in the act of committing a crime). |

| ↑6 | For years afterwards this area was known as Jerry’s Hill. |

| ↑7 | Gibbeted bodies were left on the gibbet for weeks and sometimes months. |

| ↑8 | Morning Advertiser, 26 January 1826, 2A. |

| ↑9 | Evening Standard, 1 February 1828, 3D. |

| ↑10 | Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 25 February 1844, 3A, lists “Jerry Abershaw, by Jerry, 2 yrs,” trained at Epsom, Mickleham by W. Lumley for Mr Drinkald. |

| ↑11 | 29 March 1842, 3F |