by David E. Coke

Amongst the many extraordinary facts about 19th century London, one stands out as almost unbelievable – an urban myth, you might think. How could the world record for manned-flight distance possibly have been set by a flight from Vauxhall – in 1836, the year before Queen Victoria came to the throne? Yet it’s true. The record 480-mile flight was by the ‘Royal Vauxhall Balloon’, and took 18 hours with three passengers and well over a ton of supplies and ballast. The record stood for almost 80 years, until February 1914, when Karl Ingold managed to cover twice the distance in a similar time in his Mercedes-powered Aviatik biplane.

The sixth flight of the Royal Vauxhall Balloon set off from Vauxhall Gardens on Monday 7 November 1836, straight into the record books. This was no publicity stunt for the popular garden resort, designated ‘The Royal Gardens Vauxhall’ by Royal Warrant in 1822. November after all was very much in the Gardens’ closed season, and there was no pre-publicity. Indeed, this flight was kept a secret until lift-off, its main purpose being experimental. Vauxhall Gardens was chosen as the launch-pad as it had the right facilities and because the proprietors, Frederick Gye and Richard Hughes, had commissioned and paid for the construction of the vast new balloon. It cost them around £2,100 (well over £100,000 in today’s money), including about £700 (£34,000) for the silk alone, to meet the specifications of its pilot, the aeronaut Charles Green.

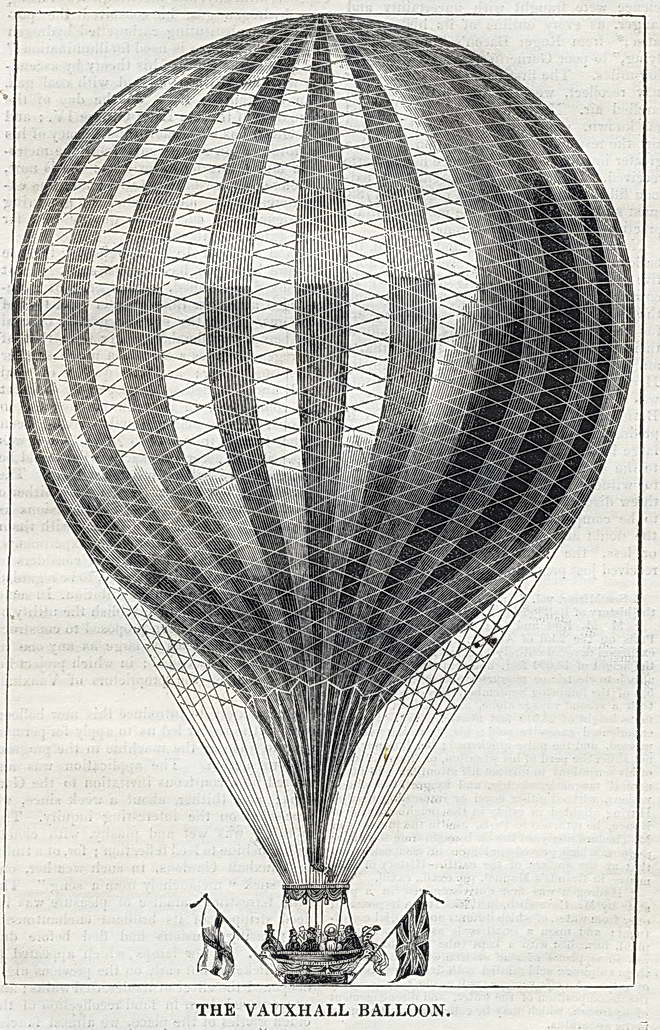

Fig. 1. ‘The Vauxhall Balloon’, from The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction, no. 796, 17 September, 1836.

Green (1785–1870) was a professional balloonist. Having realised early on the disadvantages of hot air and of hydrogen as lifting agents, he had made his first ascent, in a balloon filled with coal gas, on 19 July 1821. Green eventually made over 500 balloon ascents in his career – his 500th being a perilous night flight in early September 1852, accompanied by eight passengers including the writer Henry Mayhew. By 1836, however, Green had completed 220 flights and was famed as the most experienced and expert balloonist in the country. He had designed the new ‘Royal Vauxhall Balloon’ not only for distance flights, but also with substantial extra lifting capacity to carry passengers and equipment to conduct scientific experiments. This meant that, because of the lesser lifting-power of Green’s favoured lifting-agent, coal gas, as against the more expensive hydrogen, the new balloon had to be enormous. This suited the Vauxhall Gardens proprietors, who wanted their spectacular new balloon to be as visible as possible for as long as possible after take-off. At 80 feet high and 50 feet broad, this was not hard, the effect heightened by the 44 alternating crimson and white silk gores that made up the envelope of the balloon (Fig. 1), all coated with a special varnish to prevent the escape of gas. Nearly 2,000 yards of specially-woven Spitalfields silk was used, and the other statistics, like the 85,000 cubic feet of gas contained by the envelope, fall into line behind this. The original wicker-work gondola or ‘car’, supported by ten ropes, and draped with purple and crimson velvet, was just 9 feet by 4 feet, decorated at each end with a large gilt eagle’s head (Fig 2).

Detail from a Vauxhall handbill advertising ‘One More Double Ascent’ on 4 September 1837, showing clearly the two eagles’ heads, and other features of the gondola.

For this record-breaking flight, the gondola had to contain not only a fortnight’s food and drink (in case of landing in a wilderness), but also a ton of sand ballast, much apparatus, including a 1,000-foot length of rope, a barometer and telescopes. Then there was the baggage of the three men aboard. As well as Charles Green himself, there was the Irish writer, musician and keen balloonist Thomas Monck Mason (1803–1889), who was to write a record of the journey.[1]Thomas Monck Mason, ‘An Account of the Late Aeronautical Expedition from London to Weilburg, Accomplished by Robert Hollond Esq., Monck Mason, Esq., and Charles Green, Aeronaut.’ It was published … Continue reading They were accompanied by the expedition’s backer, Robert Hollond (1808–1877), a lawyer and politician. Hollond was with Green on the maiden flight of the Royal Vauxhall Balloon on 9 September, when it flew 26 miles to beyond Gravesend in 80 minutes.

Hollond hired the balloon from the proprietors of Vauxhall Gardens for his record-breaking flight, and he paid for the necessary supplies and preparations. All three men had to be provided with passports for the countries in which they might land. The passport the travellers actually used (it was signed by Hollond) still exists and is now housed in the Cuthbert–Hodgson Collection at the National Aerospace Library, at Farnborough. The balloonists’ supplies of food and drink might sound excessive, even for a fortnight’s provision; they included 40lbs of ham, beef, and tongue, 45lbs of chicken, as well as preserves, sugar, bread and biscuits. On top of this, Hollond thought it necessary to stow two gallons each of sherry, port, and brandy. Refreshments on this scale are likely to have been supplied by the kitchens at Vauxhall Gardens, the only London caterer of the time working on that scale.

The three men could just about squeeze into the gondola because as much stuff as possible – cloaks, bags, barometers, cordage, wine jars, spirit flasks, barrels of wood and copper, speaking trumpets, telescopes and lamps – was hung on hoops. There was also a coffee-machine, heated with slaking quick-lime. On top of everything else, the Royal Vauxhall Balloon was equipped with a ‘Bengal’ light (a slow-burning vivid blue firework) to lower at night to see how high they were. The base of the gondola was cushioned, in case the travellers needed to sleep, but it is hard to see that there can have been any space for them to do so, even one at a time.

The First Airmail Letter Ever?

Final preparations for the great flight, the purpose of which was to test the theories formed by Green from his extensive experience, began at 7am on 7 November 1836, with the balloon being slowly filled with coal gas, and the gondola with supplies. All being ready, at 1.30pm, the Royal Vauxhall Balloon took off on this sixth and most significant flight, heading south-east towards Paris. They passed over Rochester, over Canterbury, where, at 4pm they dropped a note for the mayor by parachute (the first airmail letter?), and then Dover and across the Channel. As night fell there were some anxious moments caused by the accumulation of dew on the balloon, but Green kept the balloon aloft, and after passing Calais the trio brewed coffee on their slaked-lime stove, later amusing themselves by lowering fireworks over labourers in the fields and shouting at them through a loud-hailer to see their amazed and terrified reactions. Their journey took them over Ypres, Courtrai, Lille, Oudenaarde, Brussels, Namur, Liège (where they lost their coffee-pot), Spa, Malmedy and Koblenz.

Monck Mason’s account of the flight does not say whether the men slept or not, but there was always somebody on watch. At about 3.30am, and at a height of about 12,000 feet (3,660m), the three were alarmed by three sudden explosions, which turned out to be merely the silk sections expanding in a thinner atmosphere. It was intensely cold, so they probably could not sleep in any case. They were certainly all awake before sunrise the following morning. Having passed over great tracts of snow, the party thought they might be over one of the German states or possibly even Poland, so they decided to land when they could find a suitable spot rather than risk blundering into the trackless wastes of Russia. They accordingly landed at 7.30am, and, on landing, discovered from local inhabitants who had, as Monck Mason wrote, “for some time been shyly and timidly watching the motions of the aeronauts,” that they were in the Duchy of Nassau in Germany, about six miles from the town of Weilburg, the best part of 500 miles from London. Had they kept up speed and direction, they could easily have reached Prague the next day.

Following the descent at Weilburg, and Green’s decision that the balloon had done its job, the goods from the gondola were cleared out with the help of the locals, encouraged by a ‘liberal distribution of the brandy and other liquors’ they had brought with them; so, by midday, they were ready to be taken to the town, where they ‘experienced the kindest reception from the Prince and people of Nassau.’ The church in Weilburg still boasts a stained-glass panel commemorating the event, although there is no reciprocal memorial in Vauxhall. After spending almost two weeks there, the party began their journey home – by carriage – taking note of the contrast of modes of travel, both in terms of speed and comfort. The reasonably smooth balloon flight had averaged a speed of more than 25mph, which no carriage could hope to emulate. The travellers had to make do with the coal gas already in the balloon because they could neither transport spare gas nor make any more in inflight. Coal gas was not manufactured in Nassau, hence the return journey by land of the men and their now-deflated Royal Vauxhall Balloon.

Before returning to London, Charles Green stopped in Paris, making two ascents of the balloon there, on 19 December 1836 and on 9 January 1837 (at 1.30pm), from the Barracks on the Rue du Faubourg Poissonnière, for which Green offered seats to up to ten ladies and gentlemen as passengers. On the handbill for the first of these ascents, the balloon is called the Royal Vauxhall Nassau Balloon; on its return to Vauxhall the balloon was duly re-christened the ‘Nassau Balloon’, and later, on 10 July 1838, under the patronage of the Duke of Nassau, the ‘Royal Nassau Balloon’. The ‘Duke of Nassau’s Day’ was celebrated at Vauxhall on that day, in the unavoidable absence of the Duke himself, who had been thrown from his horse and injured, so was unable to attend.[2]Vauxhall Gardens Wine Account Book [53.32/1]

The story of the Royal Vauxhall Balloon was retold many times over several years, and the balloon’s fame spread over the whole world for its outstanding achievement. The artist J.M.W. Turner was fascinated, and pleaded with Robert Hollond to make a sketch of what he had seen – especially the tops of clouds, and how the sunlight fell. Robert Hollond commissioned E.W. Cocks (b.1803), an in-house artist at Vauxhall Gardens, to produce a series of seven small paintings of the Weilburg flight for his private collection. Cocks himself had been a passenger on the second flight of the Royal Vauxhall Balloon, on 21 September, when it flew a mere seven or eight miles to Bromley, in 40 minutes.

Fig. 3. W.J. Taylor, portrait head, in profile, of ‘Charles Green Aeronaut’, from the medal struck in memory of the Nassau flight, c.1837.

Fig. 4. Reverse of the Nassau medal, with a balloonist’s-eye-view of Weilburg, and the balloon itself, top left.

Even though Charles Green was awarded no medal, a bronze medal was, in fact, struck in honour of his flight, with Green’s portrait head, in profile, on the obverse, and a view of Weilburg on the reverse (Figs. 3 and 4). This was designed and made by William Joseph Taylor (1802–1885), possibly to the commission of Robert Hollond. It is now a very scarce and precious souvenir of Green’s achievement, with only five in public collections in the UK and the US together, and two or three in known private collections, which may indicate that only a few were ever produced.

Fig. 5. Robinson after Hollins, ‘A Consultation Previous to An Aerial Voyage from London to Weilburg in Nassau.’ Engraving, 1843. Portraits of (left to right) Prideaux, Hollins, Milbourne James, Hollond, Mason, Green. This print was originally sold for the huge price of two guineas.

At the same time as this medal was being struck, a portraitist and friend of Robert Hollond, called John Hollins painted a group portrait of all those involved on the venture, called ‘A Consultation Previous to An Aerial Voyage from London to Weilburg in Nassau.’ Monck Mason stands at the right of a carpeted table with a map on it, with Green sitting to the right holding a telescope and Robert Hollond to the left. To the left of them stand three men – Walter Prideaux on the left grasping a walking stick in his gloved hand, with Hollins in the traditional pose of the self-portrait looking out at the viewer, and, behind Hollond, Sir William Milbourne James. Through a window, the red-and-white striped balloon can be seen ready for the ascent. Both Prideaux and James were friends of Hollond, both well-connected lawyers, and both probably involved in obtaining or drafting the necessary paperwork for the voyage. The painting, exhibited at the Royal Academy (no.513) in 1838, is now in the National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG 4710). Five years later, in 1843, an expensive (presumably fund-raising) engraving was made of Hollins’ painting (in the same orientation) by John Henry Robinson (1796–1871) (Fig. 5).

Unhappy Landing and ‘Vauxhall – the Movie’

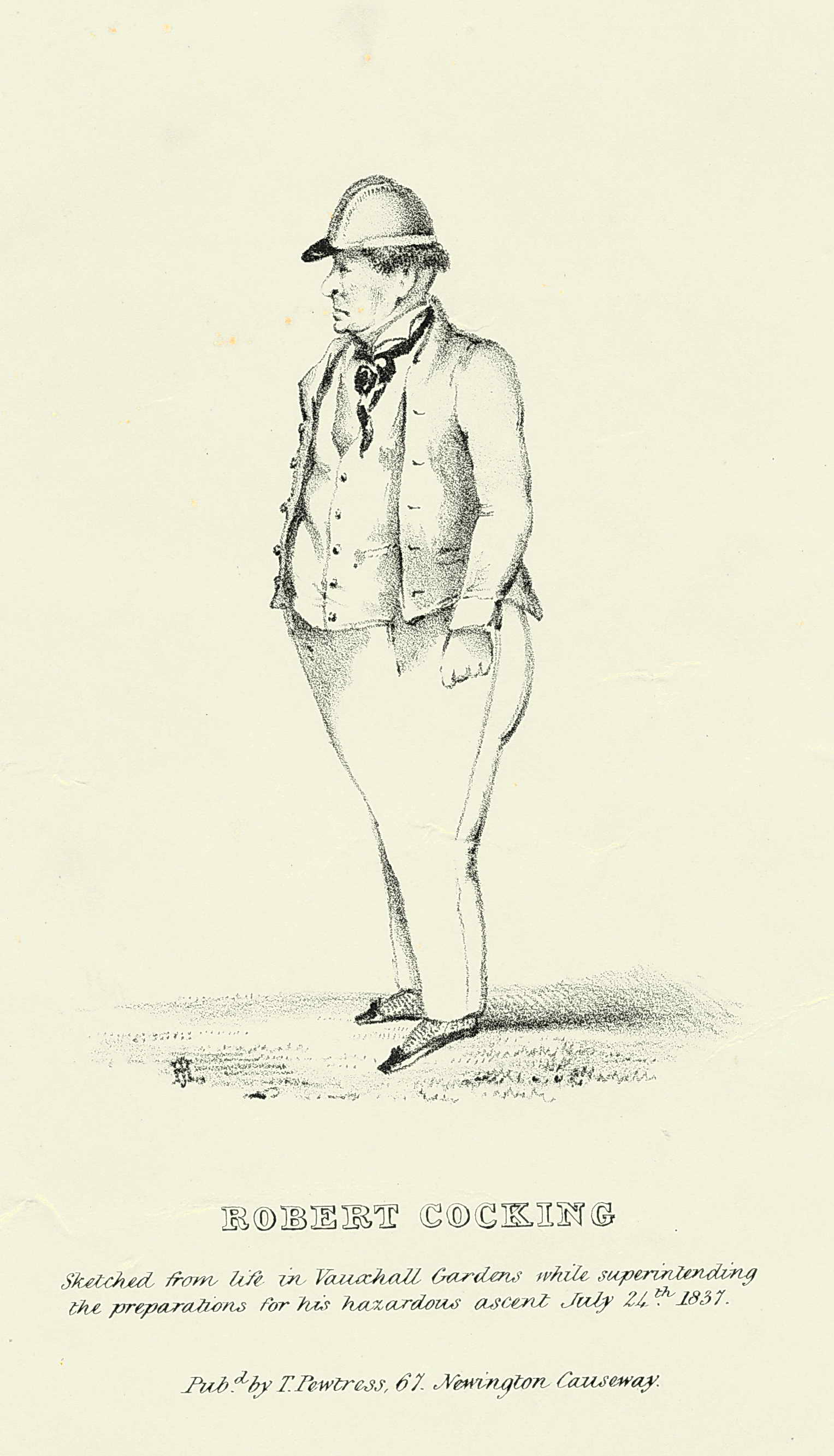

It was unfortunate that the year after the Weilburg flight, on 24 July 1837, the Nassau balloon, as the only balloon capable of carrying such a weight, became the vehicle for lifting Robert Cocking’s revolutionary new ‘parachute’ to almost a mile high before Cocking released his ludicrous machine to achieve lasting fame as the first parachute fatality in the world (Fig. 6). After this tragic event, balloons inevitably lost some of their glamour and appeal. William Taylor had originally intended to issue his medal with two different reverse designs – the view of Weilburg on some, and Robert Cocking’s no less famous fatal descent on others. Clearly he decided against this alternative reverse in the end, as none appear to survive.

Fig. 6. ‘J.H.’, ‘Robert Cocking, Sketched from life in Vauxhall Gardens while superintending the preparations for his hazardous ascent July 24th. 1837.’ lithograph.

Even though the Nassau flight may not originally have been intended as a public attraction, it inevitably became one, and, in fact, the Vauxhall proprietors capitalised on this with a vast ‘Grand Moving Panorama’ of the voyage, to show their visitors the following year. This was not yet early cinema, but a roll of painted canvas 75,500 feet long, wound between two rollers, so that about 400 feet was visible at any one time, probably about 20 or 30 feet high and probably illuminated from behind. Whether it was a view of the balloon passing over the landscape, or a continuous view from the balloon itself (as I suspect), history does not relate, but it apparently showed in fine detail the epic voyage from Vauxhall, over Chatham, Dover, the Channel, Calais, Brussels, Koblenz, and the descent near Weilburg. For those who had never been higher than a few feet, or travelled more than a few miles, it must have been a thrilling sight.

Following their classic flight, the three aeronauts returned to their daily lives; Robert Hollond of Stanmore Hall in Middlesex became Whig MP for Hastings, the polymath Thomas Monck Mason wrote the 52-page account of the flight. Charles Green, naturally enough, continued in his chosen profession, and successfully completed 526 flights since his first on the day of the coronation of King George IV in 1821, before he finally retired, after several comebacks as ‘the Veteran Green’, in 1854. His wife Martha (née Morrell) and his son George joined him in his business, as did several other members of his extended family, including Charles’s brother Harry, and themselves became successful balloonists. The family were well known to the dentist and dilettante Theodosius Purland, who wrote of them:

All his family were exceedingly illiterate and vulgar; and yet for all his vulgarity, the instant he [Charles] touched the Balloon in Vauxhall Gardens, or anywhere else, he became the gentleman and the man of science. The transformation was complete![3]Cyril Bowdler Henry, ‘The Unique Scrap-books of Theodosius Purland, MA, PhD, 1805-1881.’ London: Royal College of Surgeons, 1962. p.11

Henry Mayhew, in his vivid story about Green’s eventful 500th flight, also recorded his impressions of Charles Green, ‘the old ethereal pilot’, after they had landed and the Nassau Balloon was all packed up. During the flight Green had been ‘taciturn and almost irritable’, but ‘now he was garrulous, and delighting all with his intelligence, his enterprise, his enthusiasm, and his courtesy.’

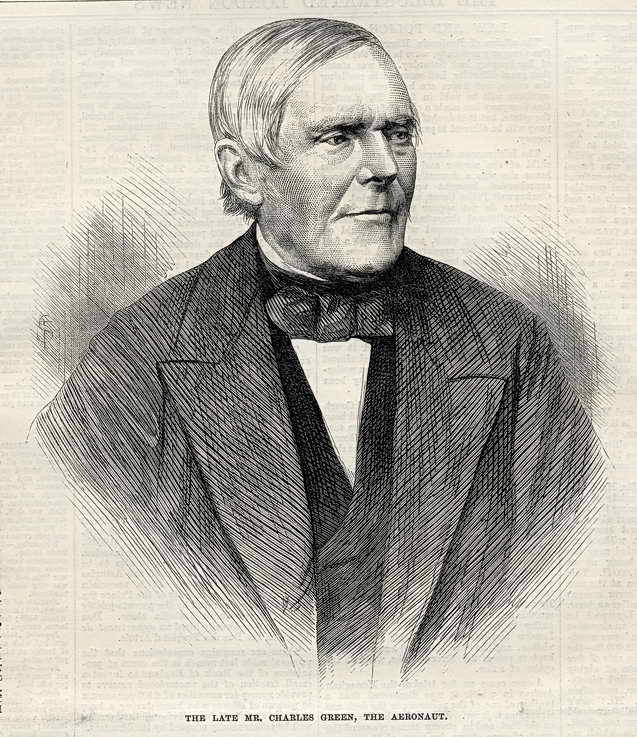

Fig. 7. ‘T.S.’, Portrait of Charles Green in old age, from the Illustrated London News, 16 April 1870, engraved from a photograph by Mayall. This illustration accompanied Green’s obituary.

Charles Green was to achieve the records for distance (480 miles), altitude (over 27,000 feet or 5 miles) (10 September 1838) and possibly speed too (80mph, on the same occasion). A nice portrait of him in older age accompanied his obituary in The Illustrated London News of 16 April 1870 (Fig. 7). Green died on 26 March that year, not aloft but at his home, Arial Villa in Holloway. He was 85. The British Balloon and Airship Club named a trophy named after him, the Charles Green Salver, which is decorated with an engraving of the Nassau Balloon, and was presented to the balloonist in 1839 by Richard Crawshay, a grateful passenger. It has since been presented by the British Balloon and Airship Club for exceptional flying achievements. In recent times winners have included Richard Branson and Per Lindstrand in 1988, for the first crossing of the Atlantic by hot-air balloon, as well as to Brian Jones and Bertrand Piccard for their the first round-the-world flight by balloon (1990), and no less than six times to David Hempleman-Adams between 2001 and 2012.

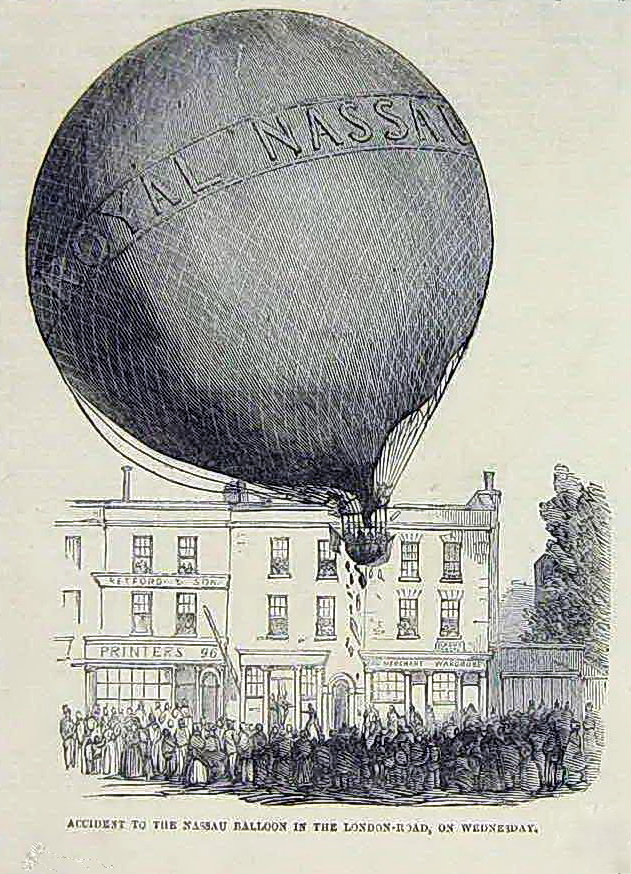

Fig. 8 ‘Accident to the Nassau Balloon in the London Road.’ From the Illustrated London News of 28 July 1849. The building damaged in the accident was a ‘Ladies School’.

Of the eventual fate of the Royal Nassau Balloon itself, I can find no record. Charles Green and his family continued to fly the balloon well into the 1850s, not without both dangerous incidents (Fig.8)[4]Published in The Illustrated London News of 18 September 1852[5]One such accident was reported in The Illustrated London News on 28 July 1849, reported in the Daily National Intelligencer of Washington, USA, on 15 August. and determined competition from other balloonists; the balloon made numerous appearances in song, in comic poetry, and even embroidered onto dress silk.[6]A Gentleman’s silk waistcoat, embroidered with a repeating balloon motif, clearly the Nassau Balloon, was sold at Tennants Auctions, North Yorkshire on 29 April 2016. Green regularly lectured, and on 17 July 1840 bought the balloon itself from the Vauxhall proprietors for £500 at auction. Green flew several other balloons at Vauxhall, all with patriotic names like the Royal Victoria, the Albion (destroyed in a crash on 20 August 1845, at Gravesend), and the Coronation (presumably created for Queen Victoria’s coronation in June 1838, and always called ‘Mr. Green’s own balloon’). Sometimes the Green family would ascend in two balloons at the same time, just to emphasise the huge scale of the Nassau Balloon.

The Vauxhall proprietors’ massive original investment in the Nassau Balloon was handsomely repaid, even in its first season, when Charles Green’s balloon ascents proved a huge attraction for visitors to the gardens. They proved be a real money-spinner in the sale of tickets for passengers to travel in the balloon’s gondola on a real flight out of London. Even before the Nassau flight, on 21 September 1836, at 3.45 in the afternoon, Charles Green made the second ascent in his new balloon, with ten passengers. The proprietors had provided a new and larger gondola to accommodate more people. The charges for passengers were phenomenally high, at £21 for gentlemen (around £1,000 in today’s money) and £10 10s. for ladies. Passenger tickets were also offered as prizes in Vauxhall’s lotteries, with tickets selling at one shilling each. The third flight of the balloon, on 27 September, achieved the 33 miles to Chelmsford in less than an hour, with the ill-fated Robert Cocking as a passenger.

Vauxhall’s proprietors paid Green £980 for his participation in their 1837 season, plus the income from two seats in the balloon. Even though it was not the original intention, the success of the Nassau flight gave a huge boost to the fortunes of Vauxhall Gardens in following seasons as well; it would be fair to say that Charles Green, with his regular flights, illuminated night-flights, parallel running races (following his balloon flights but on the ground), and especially his high ticket prices for passengers, was responsible for keeping the gardens in credit when many other pleasure gardens were failing. Over the 14 balloon days in 1838, for instance, the total income was £6,446, whereas it was only £5,544 for all the other 59 nights. Illustrations of the Nassau Balloon making its ascent over the gardens can be found in the journals and periodicals of the 1840s (Fig. 9).

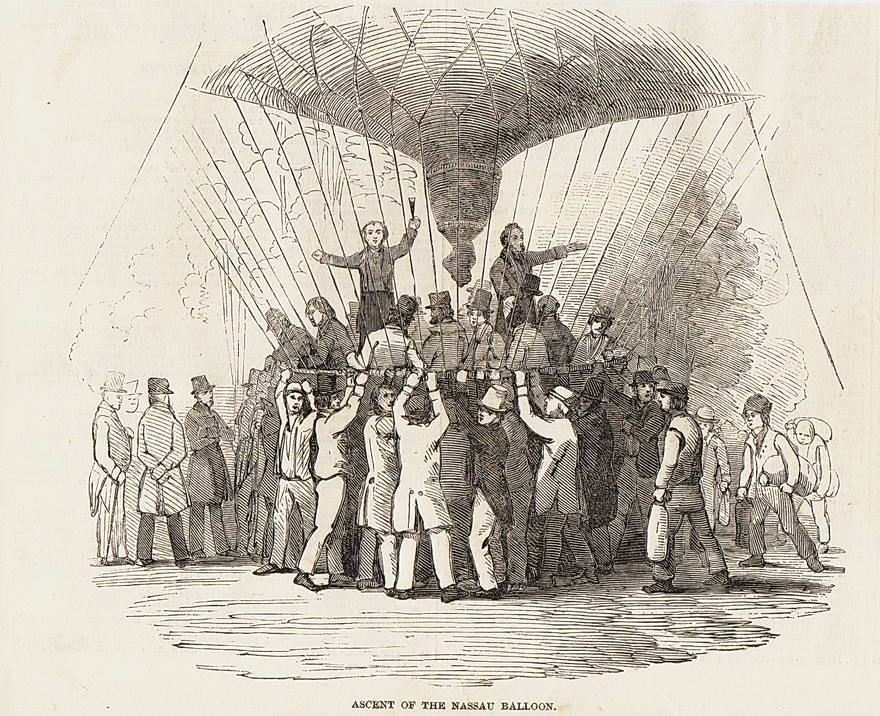

Fig. 9. The Ascent of the Nassau Balloon from Vauxhall Gardens, on Saturday 22 June 1850; The Illustrated London News shows the balloon rising up over the stupendous three-dimensional diorama of The Kremlin, constructed on Vauxhall’s ‘Waterloo Ground’.

Monday 3 July 1854 saw the last recorded ascent of Green’s Great Nassau Balloon at Vauxhall, following a lottery for six seats in the car. A year earlier (June 1853) a brief paragraph had appeared in George Cruikshank’s ‘Comic Almanack’ satirically predicting that “The veteran Green, by the announcement of his 8000th ascent, suspended by warranted unsafe cords, will prove that, in spite of his vast age and experience, he is not yet old enough to know better.” Even in his 70th year, Green clearly did not consider himself so. After 1854 however, balloons drop off Vauxhall’s advertising literature, although the Nassau continued to be flown elsewhere around the country; Fig. 10 shows a detail of the gondola, with twelve passengers on board, immediately before an ascent at Cremorne Gardens, Chelsea, in 1842. Another celebrated famous ballooning venue was the Montpellier Gardens in Cheltenham, where the Nassau balloon made an ascent on 3 July 1837; ten weeks later, an unfortunate chimpanzee named Mademoiselle Jennie was dropped from the Nassau Balloon in her own ‘parachute’; she survived the descent, to be reunited with her owner, the landlord of a local pub, who was probably more interested in his publicity than in her well-being. The Nassau balloon was eventually sold to Henry Coxwell, one of Green’s younger competitors, who continued using it until 1873, with some reconditioning. The likelihood is that it just became worn out after almost 40 years of use, and was scrapped.

Fig 10. ‘The Ascent of the Nassau Balloon’, showing just the gondola and people just before an ascent at Cremorne Gardens, Chelsea. From the Illustrated London News, 25 July 1846.

Even though the phenomenal flight to Weilburg was no myth, it certainly became the stuff of myth, with stories of Charles Green having flown to the Moon, and an article in Punch magazine speculating on the giant balloon that could land ‘a thousand troops in China in 24 hours.’[7]Punch, volume 3, 1842, p.155 In the 1840s, Charles Green made plans for a transatlantic flight, never realised, which induced an Austrian printmaker, Johannes Zinke, to produce a satirical print showing Green’s great balloon landed in the Antipodean Islands of the south Pacific, much to the wonder of the locals. The transatlantic flight proposal was picked up by the American writer Edgar Allan Poe, who wrote a hoax story for the New York Sun of 13 April 1844, trumpeting the astounding news that the Atlantic had been crossed by the balloon in just three days. This brilliant hoax caused a public sensation at the time, spreading the fame of the three aeronauts throughout the United States. Charles Dickens, in his first published book Sketches by Boz (1836–7), includes a description of a day-time visit to Vauxhall Gardens, during which the Green family ascend in two balloons. George Cruikshank’s frontispiece illustrates the ascent of the Nassau Balloon from the Gardens, with only Charles Green and an unnamed peer aboard, cheered off by a huge and enthusiastic crowd below (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11. George Cruikshank, frontispiece to Charles Dickens’ ‘Sketches by Boz’, Series 2, of 1837. [Courtesy of the US Library of Congress photographic division, digital ID cph.3g07510.]

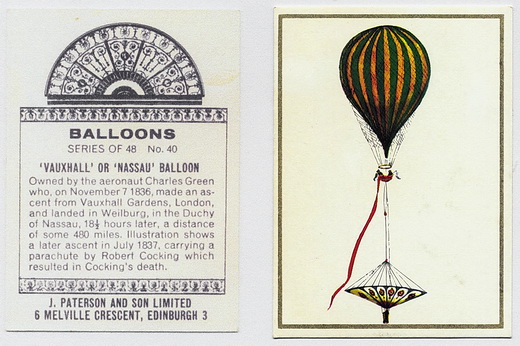

Fig. 12. A trade card produced by Patersons of Edinburgh, plumbers, c.1960, showing the ascent of the Nassau Balloon with Robert Cocking’s parachute suspended beneath it in 1837.

Green’s record-breaking flight from Vauxhall 181 years ago was a phenomenal achievement at a time when ballooning had become little more than a gentleman’s entertainment. He pioneered the use of coal gas instead of hydrogen, he proved the efficacy of the ‘trail-rope’, still in use today, and he demonstrated that gas balloons were capable not only of safe, sustained heavier-than-air manned flight, but also of considerable speed, if the correct height could be reached, and of changing direction by changing height, so catching different winds. He also showed convincingly that passengers in a balloon did not suffer from lack of oxygen, nor were they frozen solid by the colder air, both fears that had been expressed by other aeronauts. Under Green’s expert leadership, ballooning became very much safer and more controllable than before. More than anything, however, it is thanks to Charles Green that ballooning became the serious and respectable occupation and sport it still is today.

For further information, See also Tim Robinson’s 2012 article ‘Balloon Pioneer Charles Green’ at: https://www.aerosociety.com/news/balloon-pioneer-charles-green-the-parachuting-monkey/

All images © David Coke except Fig. 11.

Ready reckoner: 1 foot = 0.3m; 1 yard = 0.9m; 1 mile = 1.6km; 1 gallon = 4.5l

References

| ↑1 | Thomas Monck Mason, ‘An Account of the Late Aeronautical Expedition from London to Weilburg, Accomplished by Robert Hollond Esq., Monck Mason, Esq., and Charles Green, Aeronaut.’ It was published in London by F.C. Westley, in 1836, and by Theodore Foster in New York, in 1837. An enlarged illustrated version called ‘Aeronautica’, with five lithographic plates and a frontispiece, was published in London by F.C. Westley in 1838. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Vauxhall Gardens Wine Account Book [53.32/1] |

| ↑3 | Cyril Bowdler Henry, ‘The Unique Scrap-books of Theodosius Purland, MA, PhD, 1805-1881.’ London: Royal College of Surgeons, 1962. p.11 |

| ↑4 | Published in The Illustrated London News of 18 September 1852 |

| ↑5 | One such accident was reported in The Illustrated London News on 28 July 1849, reported in the Daily National Intelligencer of Washington, USA, on 15 August. |

| ↑6 | A Gentleman’s silk waistcoat, embroidered with a repeating balloon motif, clearly the Nassau Balloon, was sold at Tennants Auctions, North Yorkshire on 29 April 2016. |

| ↑7 | Punch, volume 3, 1842, p.155 |