An edited version of the talk given to the Johnson Society on 17 November 2013 by Ross Davies, then Chairman of The Vauxhall Society.

Vaux-Hall, by Thomas Rowlandson, 1784

(© David Coke)

Dr Johnson and Vauxhall Gardens are inseparable from the literature of, or about, Augustan Britain. Yet at the heart of Johnson’s connections with this celebrated London pleasure resort, there lies a mystery, and behind that mystery lurks an enigma.

Vaux-Hall, by Thomas Rowlandson, 1784. Detail.

(© David Coke)

The mystery is that Augustan literature appears to offer, in George Birkbeck Hill’s phrase, no ‘direct evidence of what could scarcely be doubtful’ that Johnson so much as set foot in Vauxhall Gardens. Birkbeck Hill is silent upon this mystery, yet mysteriously certifies that Johnson ‘often dined’ at Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese in Wine Office Court, off Fleet Street, even though ‘in no contemporary writer is mention made of his frequenting [the] tavern’.[1]George Birkbeck Hill, Johnsonian Miscellanies (London: Constable & Co.,1966), vol. ii., p.91 n.2.

The enigma centres upon a much-loved watercolour by Thomas Rowlandson (1756?–1827), depicting the Vauxhall revels. Rowlandson’s Vaux-Hall (1784) is uncaptioned, but there, in the left-hand corner, a supper-party is under way. One of the revelers is a burly old gent about to lay waste to one of Vauxhall’s cold roast chickens. He could strike some readers of Transactions as familiar. Could this be Johnson? If so, then who are his supper companions if not – as captions to prints of the watercolour proclaim – Boswell, Goldsmith and Mrs Thrale? Do these captions constitute ‘direct evidence of what could scarcely be doubtful’, linking Johnson and Vauxhall? I do no more than table such questions for consideration. As Chairman of The Vauxhall Society, I have no wish to be suspected of loitering with intent upon the Johnsonian stage. [2]My synoptic Vauxhall: A Little History (London: Nine Elms Press, 2009) does not mention Johnson. I am grateful to the Johnson Society for this ‘Uttoxeter Market Moment’, in which to repent. The … Continue reading

On Boswell’s evidence, Johnson in old age approved of public entertainments as a check on private vice. Yet the sage seems to have been more at ease in the intimate and more readily-dominated arena of the tavern or private supper table than in the free-and-easy hubbub of a boozy evening in the open air amid Vauxhall’s crowds of often-boisterous strollers. That may be why Boswell could ‘scarcely recollect’ that Johnson at 61 (1770) ‘ever refused going with me to a tavern, and he often went to Ranelagh’. Tea, Johnson’s favourite tipple, is the beverage most associated with Ranelagh, a largely-indoor and therefore rainproof pleasure garden set up in Chelsea to rival Vauxhall in 1742. Ranelagh, centred upon its great Rotunda, was more select than its louche competitor on the other side of the Thames; the price of admission was two and half times Vauxhall’s shilling.

Johnson may have preferred strait-laced Ranelagh, but even so the pleasures of walking and talking there threw him into even greater dejection than usual on returning home to face the night, alone. Vauxhall, however, is such a phenomenon of Johnson’s day, and so many of his friends had personal or professional links with this pleasure resort that it seems unlikely he was a stranger, even if he went there only at the insistence of friends. The supper booth under the Orchestra is a very prominent one, and diners there sure to be noticed. To be seen at Vauxhall was a good way to plug a book; Sterne chose Ranelagh to push his sermons. Whether or not Rowlandson’s Vaux-Hall links Johnson to this pleasure garden is a question that has been puzzled over for a century and a half, a controversy recently revived by a powerful intervention on the ‘Yes’ side.[3]See David Coke & Alan Borg, Vauxhall Gardens: A History (New Haven and London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2011).

As Johnson’s circle knew them, Vauxhall Gardens date from the 1730s. In 1729, a prosperous young Bermondsey businessman, Jonathan Tyers (born 1702), acquired the lease of and began to remodel New Spring Gardens. This was then a rural tavern of dubious repute in the market garden country of Lambeth on the Surrey shore of the Thames, looking across to where the Tate Britain art gallery stands today. London was ringed with such resorts. New Spring Gardens seems to have asked a nominal admission charge. There were refreshments, and couples could adjourn to booths improvised from the discarded carriages and abandoned boats dotted around between the trees. Nightingales sang in the boughs, while below itinerant musicians might strike up. Visitors could relax, free of the summer heat, smoke and stench of the oppressive, crowded and crime-ridden streets of the capital and, in Samuel Pepys’ phrase, ‘see fine people walking’.

Until Westminster Bridge opened in 1750, the only crossing over the Thames was London Bridge at Southwark, three miles to the north-east. Watermen frequently rowed Pepys to Vauxhall and back, on occasion with his family, at other times decidedly without them. One of Vauxhall’s attractions for Pepys was the women of negotiable virtue who clustered there. It was at Vauxhall in 1712 that, as Addison informed readers of The Spectator, a masked female propositioned Sir Roger de Coverley. The irate rustic then informed the manageress that ‘he should be a better customer to her garden if there were more nightingales and fewer strumpets’.[4]The Spectator, No.383, 20 May 1712

In the 1720s Tyers summered in Vauxhall, as did Hogarth, five years his senior, and Henry Fielding (b. 1707), five years Tyers’ junior. Tyers started a Wit’s Club in the district, where he, Hogarth, Fielding and other up-and-comers could debate questions of the day over a glass or three.[5]See Martin C. Battestin, with Ruthe R. Battestin, Henry Fielding: A Life (London and New York, 1989), p.159. It was here, if anywhere, that Vauxhall Gardens came into being, for as much as a place, ‘Vauxhall’ was an idea or rather Tyers’ embodiment of that idea. He was an art lover who could afford to indulge his tastes, and held cultural interests to be an innocent pleasure that made life worth living. Fashioning a more rounded, happier and healthier personality, culture brought people together. The arts should not remain the preserve of the aristocratic and the wealthy.

With the advice and artistic contacts of Hogarth and his circle, notably the painter Francis Hayman, Tyers the visionary entrepreneur set about constructing the means by which he could bring innocent pleasure within the pockets of as many people as possible, as he would have to if the venture were to turn a profit. He combined New Spring Gardens with an adjoining ‘old’ Spring Gardens to fashion the springboard for a civilising mission, which was to give ordinary people a peaceful alternative to violent, bloody spectacles such as badger-baiting and prize-fighting with swords.

Tyers re-launched the 12-acre Vauxhall Gardens in 1732, five years before Johnson and Garrick fetched up in London. Vauxhall stood just back from the river, and since the Thames veers northwards at Lambeth, the grounds extended eastwards rather than to the south. Less than half an hour’s boat ride to or from Westminster or the City, the Gardens were within easy reach of the London of the day. Tyers now lived on site with his family. With the entrance fee pegged at one shilling (perhaps £15 today), almost anybody could afford to visit at least once in a lifetime.

This was an outdoor summer resort from May to September, closing on Sundays, but otherwise open from late afternoon until the last customer left. Mrs Thrale was to have taken her daughters Susannah (then six) and Sophy (five) to see the Gardens on the afternoon of 17 July 1777, but had to cancel because their sister Queeney, 12, had an inflamed eye.[6]Mary Hyde, The Thrales of Streatham Park (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1977), p.180. The Thrales were well-placed for coach trips to Vauxhall with or without Johnson, Southwark being … Continue reading As night fell and drink began to tell, Vauxhall grew rowdier and more louche. Respectably-dressed patrons of any social rank or sexual proclivity were welcome, footmen in livery excepted. Tyers’ objection was not to footmen, but to the uniform, which he saw as a badge of subjection, out of keeping with Vauxhall’s informal, partying spirit.

Each season, innovation followed innovation. Foremost were the gravelled walks, lined with trees, their boughs hung with thousands of whale-oil lanterns. As night fell, the lamps could be lit almost simultaneously on a signal from the proprietor’s house. Vauxhall also offered unlit ‘dark walks’, for the prospect of dalliance, amateur or professional, adding spice to Vauxhall’s appeal. On reaching the Grove, a concourse where the various walks met, strollers could pause and listen or even dine to music. The London theatres closed in the summer, whereupon many musicians exchanged their seat in the pit for one a storey above ground in the Vauxhall Orchestra. This was not a band, but a sort of bandstand, possibly the forerunner of those to follow in a thousand Victorian piers and parks. The pillars of the Orchestra supported an upper floor from which the musicians, known as the Band, played, while from the balustrade, star vocalists of the day gave their all to the strollers beneath. In wet weather, the Band, vocalists and audience would adjourn to the nearby Rotunda, a domed assembly room-cum-art gallery.

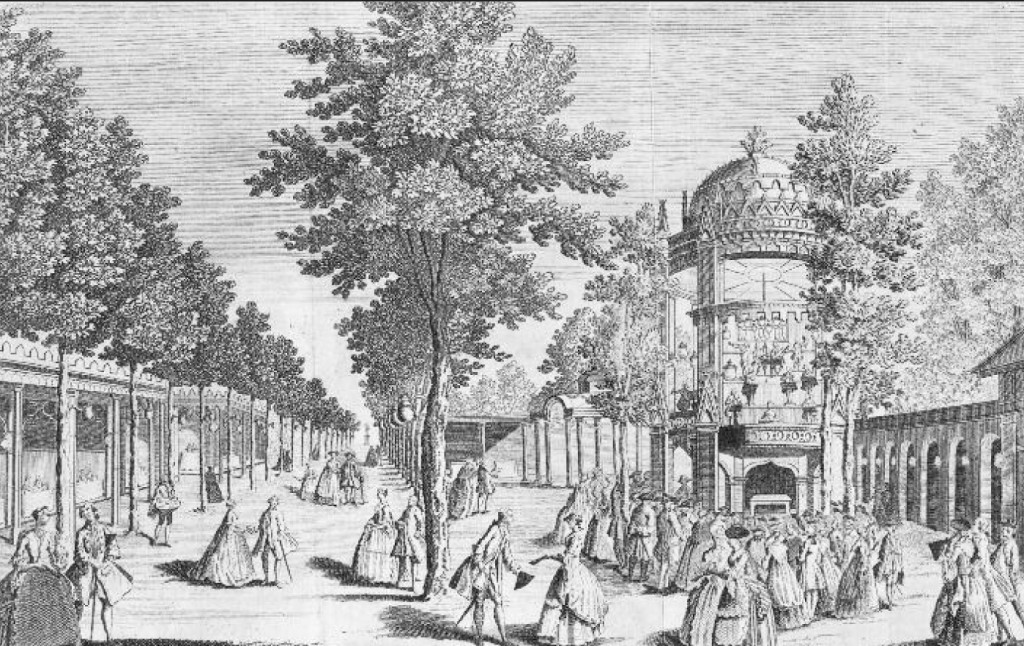

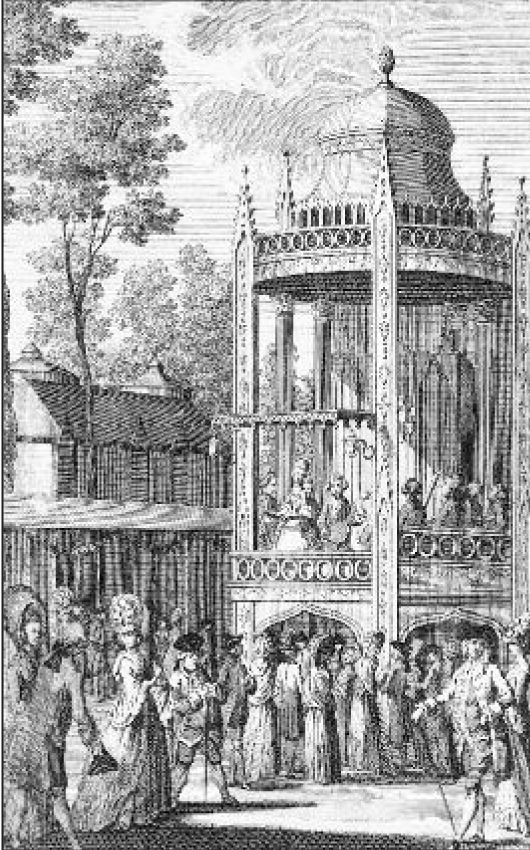

These two rarely-seen engravings of the Vauxhall Gardens of Dr Johnson and Rowlandson’s day depict strollers as they linger around the structure known as the Orchestra, serenaded by one of the Gardens’ star vocalists, backed by the Vauxhall Band. ‘A View of the Orchestra in Vauxhall Garden’ was published as the frontispiece to J. Bew’s Vocal Magazine (1778), and is an anonymous engraving. ‘A Perspective view of the Grand Walk in Vauxhall Gardens, and the Orchestra’ was published in The Gentleman’s Magazine XXXV (August 1765), again as an anonymous engraving. Both show the Orchestra as Rowlandson and Dr Johnson would have known it. Note the supper-boxes at the base of the Orchestra, as well as those lining the Grand Walk. The building to the left of the Orchestra in the Vocal Magazine engraving is the Pillared Saloon, with the Covered Walk in front. The identity of the female singers is not known.

A Perspective view of the Grand Walk in Vauxhall Gardens, and the Orchestra, 1765 (image by courtesy of David Coke)

Vauxhall Gardens opened at a time when the Grand Tour had created a vogue for Italian or French music, painting, sculpture and song. All the popular English songs of the day were aired at Vauxhall, many of them composed and written with Vauxhall in mind. The ever-astute Tyers saw that by patronising up-and-coming English artists (as well as composers, lyricists and performers), he could acquire and exhibit at Vauxhall first-rate vernacular work that was also moderately priced and likely to appeal to the wide audience he sought. Purpose-built supper booths lined the Grove, around 55 of them to begin with (1751), growing more rococo as taste veered from the Palladian. Vauxhall pre-dated public art galleries, so Tyers had the rear inside wall of each booth lined with gently moralistic English fables painted by Francis Hayman and his pupils, supplementing their income from painting theatre sets. A visit to Vauxhall might be the first occasion on which many thousands of people saw an original painting.

A View of the Orchestra in Vauxhall Garden, 1778 (image by courtesy of David Coke)

Handel (1685–1759) moved to London in 1712, soon becoming a court composer. Tyers quickly saw to it that Handel’s music dominated the Vauxhall repertory, and the composer became in effect Vauxhall’s first music director. Thomas Arne and John Worgan were to follow. Adept at marketing and public relations, Tyers pulled off stunts that made Augustan Vauxhall the place to see and in which to be seen, as well as making British or British-resident artists eager to show work there. He caused a sensation in 1738 with a sculpture in Carrara marble of Handel that he commissioned from the London-based Louis François Roubiliac and then installed at Vauxhall. This was perhaps the first commemoration in stone of a living artist. Moreover, what strollers saw was not some remote, austere figure in a toga. Here was an unkempt Handel in dressing gown and slippers, busily composing on a lyre, a celebration of hard work combining with genius in line with Tyers’ taste for the gently moralistic.[7]Roubiliac’s Handel survives in the V&A’s British galleries, as do some Hayman supperbox paintings. Tyers went on to stage a spectacular by securing the public rehearsal of Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks in 1749, five days before the performance in Green Park. Vauxhall’s owner set the seal on the Gardens’ cachet by securing royal patronage. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the patron was Frederick Louis, the Prince of Wales (1707–1751), father of George III, and very conveniently, Vauxhall’s ground landlord.

A thousand people a night might flock to Vauxhall Gardens, more on special occasions. By the time the gates closed for good in 1859, perhaps 10 million people had been through them. But had Dr Johnson? By 1859, it seems as if the sage and Vauxhall Gardens had so come to symbolise Augustan culture that they fused in the imagination. One widely-read Victorian chronicler, Edward Walford, disconsolately observes: ‘Considering that Dr Johnson was so frequent a visitor at the [Vauxhall] gardens it is astonishing that there should be so few allusions to them in the burly Doctor’s life by Boswell.’[8]Edward Walford, Old and New London, vol. vi., The Southern Suburbs (London: Cassell Petter & Galpin, undated), p.450.

Walford neither reproduces nor even refers to Rowlandson’s watercolour. On what evidence Johnson was ‘so frequent a visitor’, Walford does not say, although he claims the sage often went to Vauxhall with Sir Joshua Reynolds. Oddly enough, Walford does not rope in David Garrick, who was a friend and showbusiness rival of Jonathan Tyers. Nor does Walford tarry to ponder why there should be ‘so few’ allusions to Vauxhall in Boswell’s Life. Indeed, in my edition there are but two, one of them indirect.[9] R.W. Chapman, ed., Boswell’s Life of Johnson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1953). Johnson and Boswell first met on 16 May 1763 when Johnson was 54, and his chronicler-to-be 23. In Boswell’s journal for that month there are four references to Vauxhall, none featuring Johnson. Two relate visits to Vauxhall, during one of which an hysterical Boswell eggs on a young swell to pick a fight with a waiter. In the Life, the first reference – an indirect one – comes six years later on Friday, 27 October 1769, when, upon entering Johnson’s study, Boswell finds George Steevens and Thomas Tyers there. Tom Tyers (1726–1787), already a long-standing friend of Johnson’s, was the eldest son of Jonathan Tyers. Vauxhall’s founder died in 1767, so for two years, Tom Tyers, Johnson’s inspiration for ‘Tom Restless’ of The Idler, No. 48 (1759), had been joint proprietor and manager of Vauxhall with his younger brother, also Jonathan.

On Friday, 17 April 1778, with the second and only direct allusion, we hear of ‘that excellent place of publick amusement, Vauxhall Gardens’, which

…must ever be an estate to its proprietor, as it is peculiarly adapted to the taste of the English nation; there being a mixture of curious show, – gay exhibition, musick, vocal and instrumental, not too refined for the general ear; – for all which only a shilling is paid; and, though last, not least, good eating and drinking for those who choose to purchase that regale.[10]Boswell, Friday 17 April 1778.

Perhaps it is frustration with the faintness of the sage’s spoor that leads Walford to say Johnson ‘writes’ these few, kind words. In the Life, however, the encomium is Boswell’s. The Life first appeared in 1791, Boswell subsequently appending a footnote to deplore the doubling (in 1792), of the entrance fee to two shillings as ‘excluding a number of the honest commonalty…from sharing in elegant and innocent entertainment’. Boswell omits the sexual goings-on for which Vauxhall (like Boswell) was notorious, although such shenanigans, as well as ‘gay exhibition, musick, vocal and instrumental’ and ‘good eating and drinking’ do figure in Vaux-Hall.

Walford’s assumption that Johnson was ‘a frequent visitor’ may rest upon no firmer ground than ‘what everybody knew’ by Walford’s time. Prints of the Rowlandson and variants had long been the best-known pictorial representation of the Gardens, while soon after Vauxhall closed in 1859, millions of newly-literate Victorian readers were to come across constant allusions to Vauxhall in cheap reprints of the authors Johnson either knew or who figure in Boswell’s Life. Any list of such authors would include Fielding (Amelia, 1752), Goldsmith (Citizen of the World, 1759), Smollett (The Expedition of Humphry Clinker, 1771), and Fanny Burney (Evelina, 1778, Cecilia, 1782). In Sketches by Boz (1837), Dickens describes the Gardens in their long decline. Thackeray cements Vauxhall’s immortality in the final decade before the property developers moved in, with Vanity Fair (1848) and Pendennis (1848-50).[11]In 1955, Jean Plaidy, writing as Kathleen Kellow, published It Began in Vauxhall Gardens. More recent novels include those by Mary Brendan, Grace Elliot and Sandy Hingston.

In 1880, however, doubts arose as to what ‘everybody knew’. An art critic, Joseph Grego, averred that ‘without any sufficiently valid foundation’ the supper-box party ‘have been described…as the representatives of an illustrious and very familiar literary coterie’.[12]Grego, J., Rowlandson the Caricaturist (London: Chatto & Windus, 1880), vol.i., pp.158ff. Grego cites the memoirs of Henry Angelo (1830), a fellow student of Rowlandson’s at the Royal Academy who had accompanied the artist on drawing trips to Vauxhall. Angelo rates Rowlandson’s watercolour, without naming it, as his ‘chef d’oeuvre’ and ‘still in print’ but makes no reference to the supper party.[13]Henry Angelo, Reminiscences (London: Henry Colburn,1830), vol.ii., p.1.

Grego writes of Frederika Weichsel, a star soprano, trilling away from the Rotunda, i.e. indoors. At Vauxhall, however, the Rotunda was a domed assembly room to which singers, Band and strollers would repair only in wet weather. Yet Rowlandson clearly portrays la Weichsel performing alfresco, from the balustrade of the Orchestra as seen from the direction of the Rotunda. As Grego (1843–1908) was only 15 when Vauxhall closed, perhaps he was unable to walk the ground.

A 20th-century writer, Edwin Beresford Chancellor, either did not read or believe Grego. After the Great War, Beresford Chancellor reproduced a captioned print of Rowlandson’s Vaux-Hall and came out unconditionally for the pro-Johnson tendency:

In Rowlandson’s famous drawing of Vauxhall…Mme Weischel [sic] is seen singing to a typically distinguished company including the famous ‘Doctor’ who, with Boswell, and his friend Mrs. Thrale, appears as one might expect, to be displaying a great deal more interest in the epicurean resources of the management than in either the distinguished company or the entertainment of the musical performers.[14]E. Beresford Chancellor, The XVIIIth Century in London: An Account of its Social Life and Arts (London: B.T. Batsford,1925), p.93.

New controversies developed after the Second World War. So far, the wrangling had been over prints of the 19 by 291/2 inch (48.2 cm by 74.8 cm) Rowlandson original. Rowlandson exhibited Vaux-Hall at the Royal Academy in 1784. Since then, writes Jonathan Mayne of the V&A:

…there is absolutely no documentary record that the drawing was seen again by anyone, until 1945 when it was noticed in a small country shop and bought for a trifling sum. Thereafter Vaux-Hall passed into the hands of a West Country collector, from whose executors it was acquired by the [V&A] Museum in 1967….[15]Jonathan Mayne, ‘Rowlandson at Vauxhall’, Victoria & Albert Museum Bulletin, July 1968, vol. iv., No.3 (London), pp.77-81.

The re-appearance, and the V&A’s acquisition of, Vaux-Hall served only to deepen the mystery of the diners’ identity. The Johnsonian identifications were based upon print captions, but the original is uncaptioned. Does this mean the diners after all are, as Grego suggests, not Dr Johnson and friends? ‘Maybe’, says Jonathan Mayne (1968), for whom, ‘The group at supper in the box below [Mrs Weichsel and the Band] is traditionally supposed to consist of Boswell, Dr. Johnson, Mrs. Thrale and Oliver Goldsmith, reading from left to right.’[16]Mayne, p.79.

‘Yes’, says the V&A (1985), for whom the figures in the supper-box were ‘once (but no longer) thought to be Dr Johnson and his party’.[17]Margaret Timmers, 100 Great Paintings in the Victoria & Albert Museum (London: Victoria & Albert Museum,1985), pp.84-5.

‘No’, says David Coke (2011), who affirms that ‘in the supper-box on the left are James Boswell, Hester Thrale (who appears twice, and who, in 1784, married Gabriel Piozzi), Dr Johnson and Oliver Goldsmith.’[18]Coke & Borg, p.238. Coke argues that the print, engraved by R. Pollard, aquatinted by F. Jukes and published by John Raphael Smith (1785) sports a caption that is ‘authorised’ (approved by Rowlandson). We see immediately beneath the image and to the left ‘Drawn by T. Rowlandson’ rather than a mere ‘Rowlandson del.’, which for Coke points towards Rowlandson’s direct collaboration. So too does the fact that painting and print are the same size, indicating that the printmakers had the watercolour on hand as they worked, difficult without the artist’s say-so. Rowlandson, Coke suggests, would have wanted to profit from print sales, particularly so if he were going to give away the original.[19]Conversation with David Coke.

Mystery lingers on even if we accept, as the V&A now seems to do, that the Vauxhall diners are Johnson and company.[20]The V&A website says of Vaux-Hall, ‘it is possible to identify many well known people’, including Johnson, Boswell, Goldsmith and Mrs Thrale (no mention of Mrs Piozzi, though). … Continue reading How likely is it that Johnson would have been carousing in Vauxhall Gardens in 1784? By then he was ill and near death; even had he been well, would the sage have been seen in company with Mrs Thrale? By 1784, she was a widow and estranged from Johnson over her attachment to and then (on 23 July of that year) marriage to Gabriel Piozzi. So far, that’s two of our four revellers – Johnson and Mrs Thrale/Piozzi – out for the count, three when we recall that by 1784 Goldsmith had been ten years dead. That leaves Boswell. He was in London in the summer of 1784, and last saw Johnson on 30 June at dinner in Sir Joshua Reynolds’ house. The previous winter, Johnson had been so ill that he was unable to leave the house for 129 days in succession. It seems unlikely that the Rowlandson supper-party in Vauxhall Gardens did take place, at least not in 1784, indeed not after 1774, the year Goldsmith died. And, as David Coke suggests, in pointing out these and other anachronisms in the captions, had such a Johnsonian party taken place at any time at all, what are the chances that not one of the participants would have left a record?[21] Conversation with David Coke. What could Rowlandson be playing at?

Coke supplies an answer. First, having named the supper-box party and others, he directs attention to the gentleman standing against the next tree to the figure in legal/clerical black clutching a book. This figure, Coke suggests, is Tom Tyers. The gentleman, Coke argues, is ‘probably’ Rowlandson himself, then in his late 20s. Second, the attention of the crowd in Vaux-Hall is focussed not upon any one of the horde of notables mingling there, but upon the singer. In 1784, Mrs Weichsel had for 20 years been a Vauxhall star soprano; she was 38 and on the point of retiring. Coke speculates that she and her husband Carl, an oboe player, may have commissioned Vaux-Hall from Rowlandson, or that the Tyers family did so. More likely still, Coke suggests, is that Rowlandson himself may have presented the picture to Mrs Weichsel. In 1784, she was living at No.3, Church Street, Soho, now Romilly Street; Rowlandson rented an apartment next door at No.4.[22]Coke & Borg, p.239.

Seen as a retirement gift, Vaux-Hall takes on a new perspective, one in which inclusion of the dual Mrs Thrale/Mrs Piozzi, the dying Johnson, and the long-dead Goldsmith becomes explicable. In Coke and Borg’s analysis, Vaux-Hall may now be seen as delineating not a particular event in 1784 or any other Vauxhall season. Rowlandson is summoning up a moment that never was, but nonetheless remains true to Vauxhall’s partying spirit. Vaux-Hall becomes a conspectus, a summoning-up of the notables Mrs Weichsel would have associated with the scene of her triumphs. There is no caption to the original because she knew the people involved. With the print struck from the original, however, Rowlandson and his publishers were aiming at a wide public, and had every motive to name celebrity names.

Coke nonetheless remains flexible on the Johnson enigma. Elsewhere in the print, he says, we see representatives of royalty, aristocracy, gentry, wealth, fashion, as well as of the military, the law, church, trade, journalism and harlotry. The supper-box group could well represent not just writers, but dramatists, poets and, above all, the learning, wit and wisdom for which Tyers intended Vauxhall to be known. Who better than Johnson to serve Rowlandson as the archetype of those values? Nobody has yet come up with an Augustan notable who better fits the bill or more resembles Rowlandson’s diner than Johnson. Other celebrities named in the print and its variants lack ‘direct evidence’ of their frequenting Vauxhall.[23] Conversation with David Coke. Without doubt, the artist himself frequented the Gardens, whether or not he came across Johnson. Of Vauxhall, Angelo writes, ‘Rowlandson…and myself have often been there’.

Turning from the art to the literature of Johnson’s day, or rather to its authors, enough members of his circle have personal and professional links to Vauxhall to suggest that the sage and the Gardens may not have been strangers. Take three of Johnson’s first biographers. Tom Tyers, the part-owner, and Boswell the registered frequent patron, we have noted. Then there is Sir John Hawkins, friend of Handel and, since the late 1730s/early 1740s, of Johnson. Hawkins was knighted in 1788 for his services to the law. He was also an accomplished musician. The young Hawkins turned a penny writing lyrics for compositions to be performed and sung at Vauxhall. He also played in and on occasion led the Vauxhall Band.[24]Coke & Borg, p.125. Nobody is sure which instruments Sir John excelled at, but it seems to have been violin and cello. See Bertram H. Davis, A Proof of Eminence (Bloomington and London: Indiana … Continue reading

One form Jonathan Tyers’ patronage of the arts took in the mid-1740s was to house and feed the indigent poet and soak Christopher Smart (1722–1771) in the Proprietor’s House at Vauxhall. Smart wrote the lyrics for ‘Idleness’, a William Boyce air that was a hit of the 1744 Vauxhall season. The poet seems to have met Johnson through Grub Street, and Johnson, who ‘sincerely shared’ Smart’s ‘unhappy vacillation of mind’, covered for Smart on a monthly, The Universal Visiter, in 1756, ‘while he [Smart] was mad’. The Dictionary (1755) made Johnson sought-after, and it was around this time that Smart introduced Tom Tyers to him. Like Johnson, Tyers contributed to The Gentleman’s Magazine, and his biography of Johnson first appeared there in 1784. Sir John Hawkins’ biographer maintains that Hawkins and Johnson may have begun their lifelong friendship as early as 1739 when Hawkins, then an impecunious young law clerk, began to offer pieces to The Gentleman’s Magazine, where by now Johnson was on his way to becoming the star contributor.[25]Davis, p.19. Despite the Vauxhall connections of Hawkins, Smart and Tyers, it begins to seem as if the original link between these three and Johnson was Grub Street and journalism rather than Vauxhall.

Johnson stated that ‘No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money’. Money, or rather the lack of it, may be at the root of any relationship that he had with Vauxhall. Unlike other members of his circle, there was no payday for Johnson here. Hawkins, Smart and Tyers all wrote the lyrics for music to be performed at Vauxhall, but Johnson did not. Deaf and indifferent to music, other than to the music in words themselves, he could readily dash off light verse of a gently moral nature: ‘To Sir John Lade, on His Coming of Age’ or ‘To Mrs Thrale (On Completing Her Thirty-Fifth Year)’, for example. Yet he seems to have done so as a compliment, gift or party piece, not for money.

It seems unlikely that Johnson could or would have visited Vauxhall much, if at all, before the royal pension translated him from Grub to Easy Street in 1762. He was 25 when, in 1735, he married Elizabeth Porter (‘Tetty’), who was 21 years his senior. Two years later, he pitched up in London without her, broke and living on what was left of her money. Age, distance and infirmity – mental or physical – as well as penury kept the couple apart for much of the remaining 15 years of their marriage. We may speculate that at times Johnson might have been tempted to resort to Vauxhall for wine and women, if not song. Yet even if he had been so-minded, were wine, women – and roast chicken – not to be had much more readily and cheaply a few steps from any of his successive front doors?

Scrofulous, shambling, convulsive, habitually dressed like a tramp, what sort of figure would Johnson have cut in fashionable Vauxhall? As late as 1755 he was still liable to arrest for debt. A wifeless, childless man could live after a fashion on a shilling a day in London. How likely was it that Johnson would blow that shilling on admission to Vauxhall, home of music he could hardly hear and paintings or sculpture he could barely see? Tetty may have insisted on a pleasure garden expedition, of course. If so, it seems more likely that she, like her husband’s creation Mrs Zachary Treacle, would have dragged him, protesting, to some more modest London resort, such as ‘Hornsey Wood, or the White Conduit House’.[26]The Idler, No. 15, July 22, 1758.

Boswell says the Johnson Boswell says the Johnson of prosperous, post-pension years ‘often’ went to Ranelagh, which he, Johnson, ‘deemed a place of innocent recreation’. Ranelagh Gardens, which stood next to where the Chelsea Flower Show is held today, opened in 1742 specifically to rival Vauxhall. Assiduous party-goers would call in at both, ending up in Vauxhall. In contrast with Vauxhall’s al fresco loucheness, the socialising at Ranelagh was more genteel. Johnson, however, found that even the sedate charms of Ranelagh could be painful, for ‘it went to

my heart to consider that there was not one in all that brilliant circle, that wasnot afraid to go home and think’.[27]Boswell, 23 September 1777.

But it is not to Ranelagh but to Vauxhall that the shade of Johnson was to cling. Ranelagh folded in 1805, 44 years before Vauxhall, without becoming a name as numinous in the folk memory. It would be a rare professed Londoner of Johnson’s day who did not set foot in Vauxhall. However, Vauxhall probably was just not Johnson’s cup of tea. There was too much else going on that could distract from the conversation or compete for his hearers’ attention. Moreover, literature may have conferred upon Vauxhall Gardens a significance amounting to immortality, an importance perhaps greater for succeeding generations than for Johnson’s own. Vauxhall was but one of many pleasure gardens, as is Harrods among London department stores now. To have made a fuss about going to Vauxhall then, as to Harrods today, would be the mark of a tourist or provincial, not of a confirmed Londoner.

That said, Jonathan Tyers’ Vauxhall created the first mass audience for the arts, in particular for English music, painting and song. Vauxhall has so peopled English belles lettres, drama, fiction, history and verse that fascination sets in, and readers may feel that Johnson and Vauxhall are at one or, if not, they should be. This may explain Walford’s assumption that Johnson was a ‘frequent’ visitor and led him to attribute to Johnson’s pen words of praise that came from Boswell. The audience for Vauxhall-flavoured literature has built up over the years, and by now may far exceed the number of those who, like Johnson and his contemporaries, were lucky enough to have had the option of experiencing the real thing. Whatever we make of Dr Johnson and the Vauxhall Gardens Mysteries, long may each generation’s reading audience for the one continue to swell the audience for the other.

References

| ↑1 | George Birkbeck Hill, Johnsonian Miscellanies (London: Constable & Co.,1966), vol. ii., p.91 n.2. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | My synoptic Vauxhall: A Little History (London: Nine Elms Press, 2009) does not mention Johnson. I am grateful to the Johnson Society for this ‘Uttoxeter Market Moment’, in which to repent. The Vauxhall Society offers guided local history walks that include Vauxhall Gardens. |

| ↑3 | See David Coke & Alan Borg, Vauxhall Gardens: A History (New Haven and London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2011). |

| ↑4 | The Spectator, No.383, 20 May 1712 |

| ↑5 | See Martin C. Battestin, with Ruthe R. Battestin, Henry Fielding: A Life (London and New York, 1989), p.159. |

| ↑6 | Mary Hyde, The Thrales of Streatham Park (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1977), p.180. The Thrales were well-placed for coach trips to Vauxhall with or without Johnson, Southwark being three miles north and Streatham three miles south. |

| ↑7 | Roubiliac’s Handel survives in the V&A’s British galleries, as do some Hayman supperbox paintings. |

| ↑8 | Edward Walford, Old and New London, vol. vi., The Southern Suburbs (London: Cassell Petter & Galpin, undated), p.450. |

| ↑9 | R.W. Chapman, ed., Boswell’s Life of Johnson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1953). |

| ↑10 | Boswell, Friday 17 April 1778. |

| ↑11 | In 1955, Jean Plaidy, writing as Kathleen Kellow, published It Began in Vauxhall Gardens. More recent novels include those by Mary Brendan, Grace Elliot and Sandy Hingston. |

| ↑12 | Grego, J., Rowlandson the Caricaturist (London: Chatto & Windus, 1880), vol.i., pp.158ff. |

| ↑13 | Henry Angelo, Reminiscences (London: Henry Colburn,1830), vol.ii., p.1. |

| ↑14 | E. Beresford Chancellor, The XVIIIth Century in London: An Account of its Social Life and Arts (London: B.T. Batsford,1925), p.93. |

| ↑15 | Jonathan Mayne, ‘Rowlandson at Vauxhall’, Victoria & Albert Museum Bulletin, July 1968, vol. iv., No.3 (London), pp.77-81. |

| ↑16 | Mayne, p.79. |

| ↑17 | Margaret Timmers, 100 Great Paintings in the Victoria & Albert Museum (London: Victoria & Albert Museum,1985), pp.84-5. |

| ↑18 | Coke & Borg, p.238. |

| ↑19 | Conversation with David Coke. |

| ↑20 | The V&A website says of Vaux-Hall, ‘it is possible to identify many well known people’, including Johnson, Boswell, Goldsmith and Mrs Thrale (no mention of Mrs Piozzi, though). https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/017299/vauxhall-gardens-drawing-rowlandsonthomas/ [Accessed on: 11 July 2014] |

| ↑21, ↑23 | Conversation with David Coke. |

| ↑22 | Coke & Borg, p.239. |

| ↑24 | Coke & Borg, p.125. Nobody is sure which instruments Sir John excelled at, but it seems to have been violin and cello. See Bertram H. Davis, A Proof of Eminence (Bloomington and London: Indiana University Press, 1973), p.45. |

| ↑25 | Davis, p.19. |

| ↑26 | The Idler, No. 15, July 22, 1758. |

| ↑27 | Boswell, 23 September 1777. |