by Roger Johnson, editor of The Sherlock Holmes Journal

The Sherlock Holmes Society of London

www.sherlock-holmes.org.uk

For most of us, when we think of Sherlock Holmes and London, our first thought, of course, is of Baker Street, and then, perhaps, of Westminster, the Strand, Bart’s Hospital. All north of the river. We tend to forget transpontine London, what Holmes once called “the Surrey side”, but these southern areas provide many essential chapters in the life and career of the great detective.

Arthur Conan Doyle, as every schoolboy knows, was born in Edinburgh, went to school at Stonyhurst in Lancashire, and took his medical degree at Edinburgh University. He occasionally visited relations in London, but he didn’t move here until 1891, when he took rooms near the British Museum. Within months he had given up medicine for literature and bought a house in Tennison Road, South Norwood, where he and his family lived for the next six years.

Conan Doyle’s house at 12 Tennison Road, South Norwood

Unfortunately for our purposes, Tennison Road is not in Lambeth, however we define Lambeth.

And how do we define it? For most of Holmes’s career the name would have implied the area around the Archbishop’s palace – what you might call the real, original Lambeth – or the remarkably long, thin district administered by the parish vestry. In 1900 the Metropolitan Boroughs were created, and they served satisfactorily until they were replaced in 1965 by the London Boroughs. Well, that’s what we have now, for better or worse, so our boundaries will be those of the London Borough of Lambeth – but we shall venture now and then into foreign territory. If we had to go to Camberwell, for instance, we should be unlikely to make a point of staying on one side or the other of the border between Lambeth and Southwark, even if we could be absolutely certain where that border was.

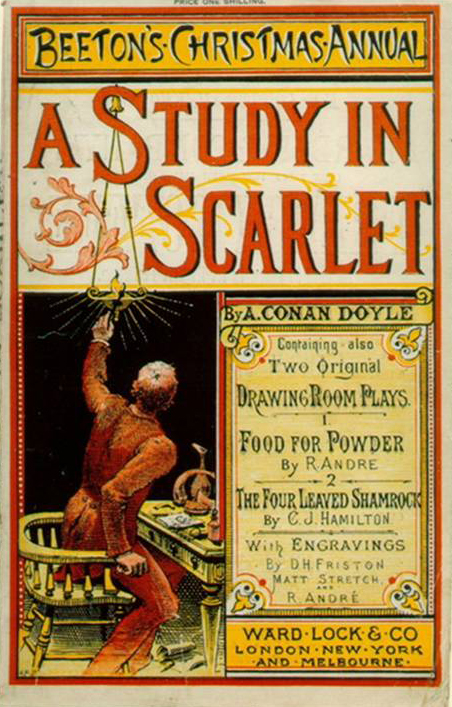

A STUDY IN SCARLET

A Study in Scarlet, published in Beeton’s Christmas Annual

The chronology of the detective’s investigations is even more disputed than the geography, so it’s probably best to consider them in the order in which they were published. The first, famously, is A Study in Scarlet, written in 1886, when the author was still in practice in Southsea, and published the following year. Dr John Watson, invalided home from Afghanistan, meets a colleague from Bart’s Hospital, who introduces him to a prospective flat-mate. Holmes and Watson move into 221B Baker Street, and after a while the doctor learns just what his new friend’s profession is. Then a message arrives, from one of Holmes’s contacts in the police:

“MY DEAR MR. SHERLOCK HOLMES:

“There has been a bad business during the night at 3, Lauriston Gardens, off the Brixton Road. Our man on the beat saw a light there about two in the morning, and as the house was an empty one, suspected that something was amiss. He found the door open, and in the front room, which is bare of furniture, discovered the body of a gentleman, well dressed, and having cards in his pocket bearing the name of ‘Enoch J. Drebber, Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.A.’ There had been no robbery, nor is there any evidence as to how the man met his death. There are marks of blood in the room, but there is no wound upon his person. We are at a loss as to how he came into the empty house; indeed, the whole affair is a puzzler. If you can come round to the house any time before twelve, you will find me there. I have left everything in statu quo until I hear from you. If you are unable to come, I shall give you fuller details, and would esteem it a great kindness if you would favour me with your opinions.

“Yours faithfully,

“TOBIAS GREGSON.”

Holmes says, “We may as well go and have a look. Come on!” And a minute later, Watson tells us, “we were both in a hansom, driving furiously for the Brixton Road”.

As they approach their destination, Watson points and says: “This is the Brixton Road, and that is the house, if I am not very much mistaken.”

Number 3, Lauriston Gardens [he tells us] wore an ill-omened and minatory look. It was one of four which stood back some little way from the street, two being occupied and two empty. The latter looked out with three tiers of vacant melancholy windows, which were blank and dreary, save that here and there a “To Let” card had developed like a cataract upon the bleared panes. A small garden sprinkled over with a scattered eruption of sickly plants separated each of these houses from the street, and was traversed by a narrow pathway, yellowish in colour, and consisting apparently of a mixture of clay and of gravel. The whole place was very sloppy from the rain which had fallen through the night. The garden was bounded by a three-foot brick wall with a fringe of wood rails upon the top, and against this wall was leaning a stalwart police constable, surrounded by a small knot of loafers.

More than anyone else I know, my late friend and colleague Bernard Davies applied Holmes’s own methods to the stories. Bernard’s specialism was literary topography. He asked: “Whereabouts exactly was ‘Number 3, Lauriston Gardens’?”

Gregson’s letter refers to “3, Lauriston Gardens, off the Brixton Road”, which suggests that the house was in a side street, but it soon becomes clear that the street outside the house was Brixton Road itself. What Gregson meant, it seems, is what Watson noticed – that the house “stood back some little way from the street”.

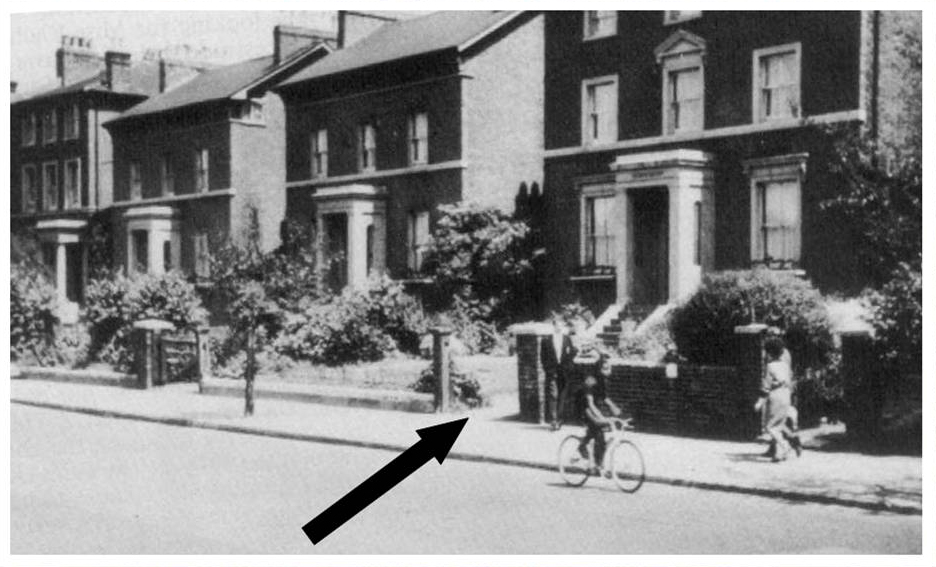

333 Brixton Road, photographed by Bernard Davies in 1962

For reasons perfectly sound but too complex to go into here, Bernard identified a row of four houses about a quarter of a mile north of Brixton Police Station. The third from the left, no. 333 Brixton Road, was a very close match for no. 3 Lauriston Gardens.

Bernard adds: “Short ‘addresses’ of the type ‘Lauriston Gardens’ no longer existed in Brixton Road at that period, though they had done earlier. The road had been built up piecemeal across wasteland, each parcel of lots — from three or four houses to as many as twenty — being named and numbered individually at the whim of the builder. This confusion lasted until January 1871, when the Post Office renumbered the entire road from end to end, and 38 ‘Places’, ‘Terraces’, ‘Villas’ and ‘Groves’ vanished into limbo overnight.”

There is a real Lauriston Gardens, incidentally – not in London, but in Edinburgh, not far from the Medical School of the University where Arthur Conan Doyle trained.

Those four houses in the Brixton Road are no longer there. They were demolished about thirty-five years ago to make way for a rather pleasant recreation ground, originally called Angell Park, and since renamed after the jazz drummer Max Roach.

During their investigation the detective and the doctor visited a couple more sites that do survive. One was the nearest telegraph office, because Holmes needed to send a wire to Cleveland, Ohio. As Bernard Davies notes: “They did not take a cab, for it was less than a quarter of a mile’s walk north of the house. Built in 1864, as it proudly proclaims on its facade, the Eagle Printing Works at No. 304, on the west side of Brixton Road, is a floridly commercial building designed to draw attention to itself. A shade Byzantine, a touch Moorish; it has the unabashed self-confidence of the age. A few years later it was converted to hold, not only Messrs. Fenton, printer and stationers, and Rogerson the shirtmaker, but also the Sub-district Post, Money Order and Telegraph Office.”

The post office itself is long gone, but the royal arms can still be seen above the door.

Next they took a cab up to Kennington, to meet PC Rance, the man who had found the body. His address was “46 Audley Court, Kennington Park Gate”.

Watson says:

Our cab had been threading its way through a long succession of dingy streets and dreary byways. In the dingiest and dreariest of them our driver suddenly came to a stand. “That’s Audley Court in there,” he said, pointing to a narrow slit in the line of dead-coloured brick. “You’ll find me here when you come back.” Audley Court was not an attractive locality. The narrow passage led us into a quadrangle paved with flags and lined by sordid dwellings.

Aulton Place, SE11

Its real name was Grove Place, entered from Milverton Street by way of that narrow slit. At the other end was an alley called Aulton Passage, leading to Kennington Place – and the name “Aulton Passage” isn’t too far from Watson’s “Audley Court”. In 1893 the whole of Grove Place and Aulton Passage was renamed Aulton Place.

Aulton Place, SE11, photographed in 2007

The fact that the “narrow slit” leads in from Milverton Street is further evidence that this is the right place. Nearly 20 years later Conan Doyle used the unusual name Milverton for a memorable character, the king of all the blackmailers, in a Sherlock Holmes story called “The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton”.

Towards the end of the investigation, Gregson visits Holmes and Watson in Baker Street. He has found out where the dead man had been lodging – Charpentier’s Boarding Establishment, Torquay Terrace – and has arrested the landlady’s son for the murder.

“My theory [he says] is that he followed Drebber as far as the Brixton Road. When there, a fresh altercation arose between them, in the course of which Drebber received a blow from the stick, in the pit of the stomach perhaps, which killed him without leaving any mark. The night was so wet that no one was about, so Charpentier dragged the body of his victim into the empty house.”

Gregson doesn’t tell us where Torquay Terrace is. We find that out later, when the real killer tells his story. It’s in Camberwell.

We mentioned Camberwell earlier. The way in which settlements have been divided among the administrative authorities, on apparently arbitrary principles, is one of the most confusing features of Greater London. Camberwell is a good example.

Dover Terrace (“Torquay Terrace”) where Mme Charpentier had her lodging house

Now, it would be absurd to suggest that Arthur Charpentier followed Drebber through the rainy streets for two or three miles from some remote part of the parish of Camberwell, until he caught up with him in the Brixton Road. Clearly Gregson knew that Torquay Terrace and Lauriston Gardens were not very far apart.

That’s because the postal district of Camberwell and the parish of Lambeth overlapped. People living in that borderland paid their rates to Lambeth Vestry, but their address was not “Brixton, South West”. It was “Camberwell, South East”. And that is where we find, in Coldharbour Lane, just the other side of Loughborough Junction, Dover Terrace, which is an admirable match for Watson’s “Torquay Terrace”.

So the first recorded adventure of Sherlock Holmes took place, mostly, within the old Parish of Lambeth. You may not be wholly surprised to know that much of the second one was also located in Lambeth.

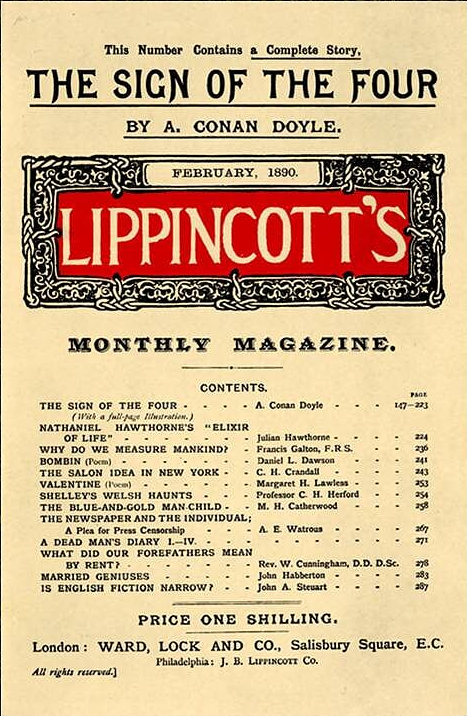

THE SIGN OF THE FOUR

The Sign of the Four: The second chronicle of Sherlock Holmes

From the Lyceum Theatre, Holmes, Watson and their client, Mary Morstan, are taken in a four-wheeled cab through the foggy streets to an unknown destination.

At first [says Watson] I had some idea as to the direction in which we were driving; but soon, what with our pace, the fog, and my own limited knowledge of London, I lost my bearings and knew nothing save that we seemed to be going a very long way. Sherlock Holmes was never at fault, however, and he muttered the names as the cab rattled through squares and in and out by tortuous by-streets.

“Rochester Row,” said he. “Now Vincent Square. Now we come out on the Vauxhall Bridge Road. We are making for the Surrey side apparently. Yes, I thought so. Now we are on the bridge. You can catch glimpses of the river.”

We did indeed get a fleeting view of a stretch of the Thames, with the lamps shining upon the broad, silent water; but our cab dashed on and was soon involved in a labyrinth of streets upon the other side.

“Wandsworth Road,” said my companion. “Priory Road. Lark Hall Lane. Stockwell Place. Robert Street. Coldharbour Lane. Our quest does not appear to take us to very fashionable regions.”

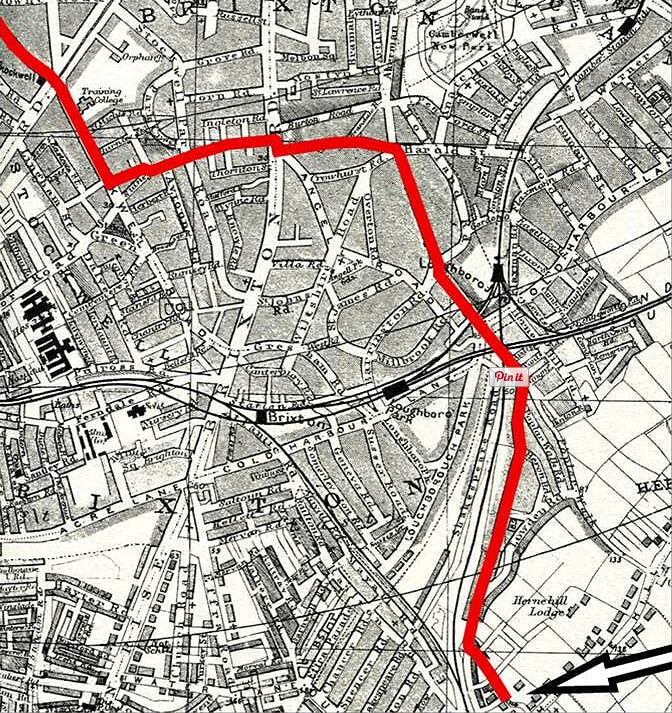

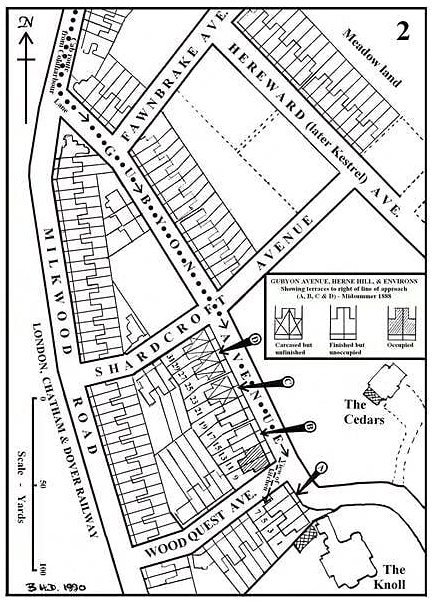

Toward the unknown region – showing the journey’s end

It is odd, as Bernard Davies notes, that Holmes should say “Robert Street”, because in 1880, at least seven years earlier, Robert Street had been merged with Park Street to form Robsart Street.

It’s also odd that he doesn’t mention the names of any of the newly laid out streets after Coldharbour Lane. This seems to confirm the notion that his detailed knowledge of the area had not been updated since the 1870s. And that in turn suggests that, as Bernard says, “Holmes must have spent at least some years of his childhood in South London, in one of those districts later engulfed in the giant boroughs of Lambeth, Wandsworth, or Camberwell.”

Watson continues his narrative:

We had indeed reached a questionable and forbidding neighbourhood. Long lines of dull brick houses were only relieved by the coarse glare and tawdry brilliancy of public-houses at the corner. Then came rows of two-storied villas, each with a fronting of miniature garden, and then again interminable lines of new, staring brick buildings — the monster tentacles which the giant city was throwing out into the country. At last the cab drew up at the third house in a new terrace. None of the other houses were inhabited, and that at which we stopped was as dark as its neighbours, save for a single glimmer in the kitchen-window. On our knocking, however, the door was instantly thrown open by a Hindoo servant, clad in a yellow turban, white loose-fitting clothes, and a yellow sash. There was something strangely incongruous in this Oriental figure framed in the commonplace doorway of a third-rate suburban dwelling-house.

No 13 Gubyon Avenue

No 13 Gubyon Avenue: “a third-rate suburban dwelling house” (photographed in 2007)

According to Bernard Davies’s researches, no. 13 Gubyon Avenue is the house that was temporarily occupied by the eccentric Thaddeus Sholto. He takes his three visitors to meet his brother at their late father’s house in Norwood – not West Norwood, which was and is a part of Lambeth, but Upper Norwood.

Pondicherry Lodge [says Watson] stood in its own grounds and was girt round with a very high stone wall topped with broken glass. A single narrow iron-clamped door formed the only means of entrance…

Inside, a gravel path wound through desolate grounds to a huge clump of a house, square and prosaic, all plunged in shadow save where a moonbeam struck one corner and glimmered in a garret window. The vast size of the building, with its gloom and its deathly silence, struck a chill to the heart.

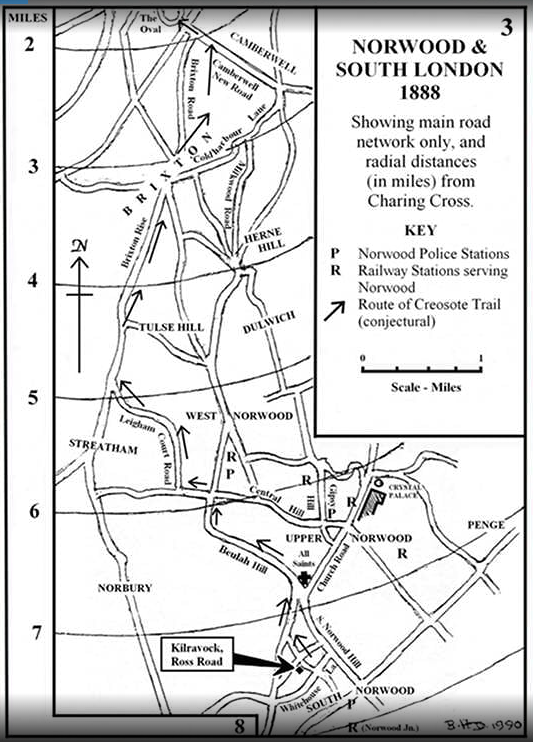

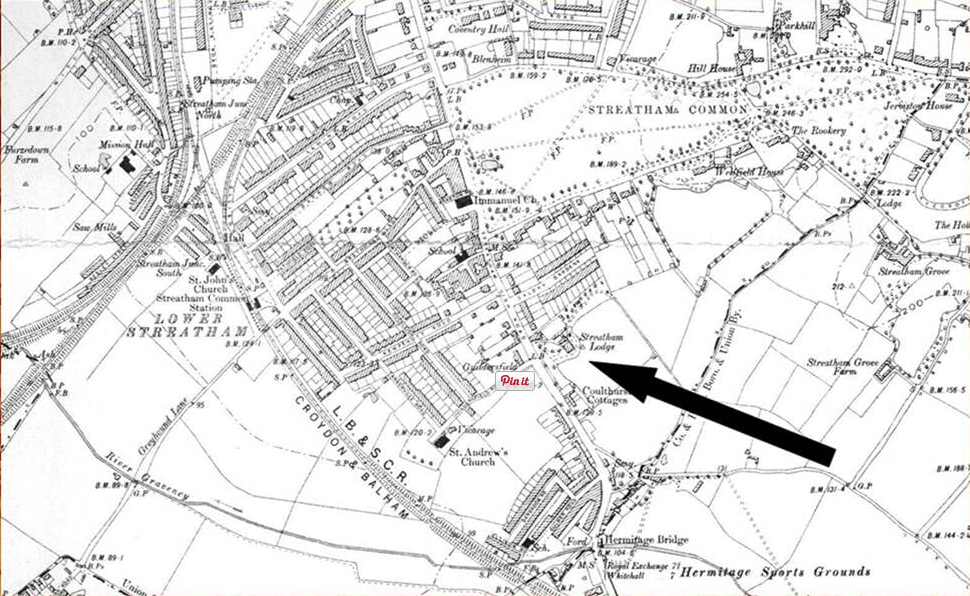

Norwood & South London in 1888

Kilravock, Ross Road (“Pondicherry Lodge”) – not in Lambeth. Photographed in 2007

Again, Bernard Davies provides an identification: in this case, the house formerly known as Kilravock, in Ross Road. But Ross Road, as you may know, is in South Norwood. So how do we account for the statement in The Sign of the Four that Pondicherry Lodge is in Upper Norwood? Bernard explains:

“Up until 1875 Ward’s Directory of Croydon had carefully defined the boundary between Upper and South Norwood as the line of Whitehorse Lane and Woodvale Road. This was the traditional boundary between two hamlets of the ancient parish and placed Ross Road firmly in Upper Norwood. By the 1876 edition, however, this arrangement was completely altered, owing to the decision by the Post Office to move the boundary for deliveries from the South Norwood office practically to the top of the hill.

“There must have been consternation among residents on the higher slopes who suddenly found themselves obliged to put ‘South Norwood’ on their letterheads. By comparison South Norwood was a declassé, nondescript area lacking in tone, which had grown up along the main road near the railway junction. Indignant letters must have been fired off to both the Directory publishers and the Post Office, and whatever they put on the top, it is doubtful if some of the more irate correspondents would ever have admitted to living in South Norwood.

“In a sense they didn’t, because the new Borough of Croydon honoured the old boundary, drawing the line between the electoral wards of Norwood Upper and Norwood South along Whitehorse Lane. So, in the electoral registers and census returns Ross Road was still entered under ‘Upper Norwood’.”

The planned meeting with Bartholomew Sholto doesn’t take place: he has been murdered. Thaddeus is sent to report the matter to the police, while Holmes and Watson investigate. There were two intruders, one of whom has rather conveniently stepped in a little puddle of creosote. Watson says: “It is not right that Miss Morstan should remain in this stricken house.”

“No,” says Holmes. “You must escort her home. She lives with Mrs. Cecil Forrester in Lower Camberwell, so it is not very far.”

“Lower Camberwell” doesn’t seem to be a recognised name. Perhaps Mrs Forrester lived in Lower Camberwell Grove – not an official address, but apparently rather a desirable area. Holmes continues: “When you have dropped Miss Morstan, I wish you to go on to No. 3 Pinchin Lane, down near the water’s edge at Lambeth. The third house on the right-hand side is a bird-stuffer’s; Sherman is the name. You will see a weasel holding a young rabbit in the window. Knock old Sherman up and tell him, with my compliments, that I want Toby at once. You will bring Toby back in the cab with you.”

Broad Street, Lambeth. Is this “Pinchin Lane”?

Pinchin Lane, we are told, is “a row of shabby, two-storied brick houses in the lower quarter of Lambeth.”

Bernard Davies notes that Mr Sherman is actually one of the most interesting characters in the entire saga:

“His claim to our attention lies in the fact that, with the exception of brother Mycroft, he is the only person ever to refer to Holmes by his Christian name, albeit prefixed by the respectful ‘Mister’. ‘A friend of Mr Sherlock is always welcome,’ he exclaims, on being woken up. This sounds suspiciously like the type of address employed by a much older man in a long and familiar relationship with a very young one. We sense the ‘Master Sherlock’ of bygone days which, in due time, it replaced.

“Of all the minor characters in Watson’s narratives, ‘old Sherman’ has the greatest claim to Holmes’s boyhood friendship. The ‘lower quarter of Lambeth’, ‘down near the water’s edge’, lies south of Old Lambeth village and the Palace, around Vauxhall. In Holmes’s day, and earlier, it was a favourite district for bird and beast stuffers and dealers. Sherman’s curious little shop was just the sort of place that young Holmes would love to frequent. We can picture him now, a thin, eager youth helping the older man with the skinning, making impressions of bird and animal tracks, bursting with questions as to the poisonous effects of vipers, and trying out an earlier model of the dog Toby with someone’s old boot.”

Toby, of course, is the ideal tracker dog. Led by him, Holmes and Watson follow the trail of the two intruders.

Watson tells us:

We had traversed Streatham, Brixton, Camberwell, and now found ourselves in Kennington Lane, having borne away through the side streets to the east of the Oval. The men whom we pursued seemed to have taken a curiously zigzag road, with the idea probably of escaping observation. They had never kept to the main road if a parallel side street would serve their turn. At the foot of Kennington Lane they had edged away to the left through Bond Street and Miles Street.

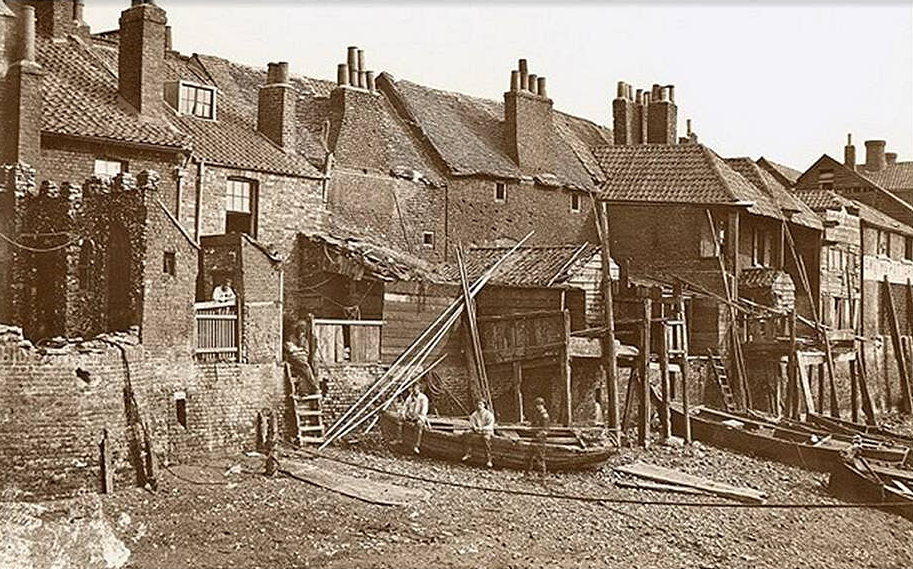

Boatmen on the Lambeth foreshore: One of them may be Mordecai Smith

From the corner of Knight’s Place, our route tended down towards the riverside, running through Belmont Place and Prince’s Street. At the end of Broad Street it ran right down to the water’s edge, where there was a small wooden wharf.

Several small punts and skiffs were lying about in the water and on the edge of the wharf. We took Toby round to each in turn, but though he sniffed earnestly he made no sign.

Close to the rude landing-stage was a small brick house, with a wooden placard slung out through the second window. “Mordecai Smith” was printed across it in large letters, and, underneath, “Boats to hire by the hour.”

And that, as far as this case is concerned, is where we leave Lambeth. Holmes and Watson take a boat across the river to Millbank. We shall catch up with them again in Baker Street.

A CASE OF IDENTITY

A Case of Identity: The fifth chronicle of Sherlock Holmes

The narrative of this curious little puzzle is set entirely in the sitting-room at 221B, but south London does feature.

The client is a very worried young woman, whose fiancé vanished, as if by magic, on the way to their wedding. She says: “I advertised for him in last Saturday’s Chronicle. Here is the slip and here are four letters from him.”

“Thank you,” says Holmes. “And your address?”

“No. 31 Lyon Place, Camberwell.”

Mosedale Street (“Lyon Place”, Camberwell) – not in Lambeth

Detail of Mosedale Street

There is no Lyon Place in Camberwell, but the name suggests that Miss Sutherland might live in Mosedale Street, near the pub called The Lion. The fact that Mosedale Street is – or, rather, was – a square rather than a straight or winding street adds some weight to the theory. Alas, that whole area west of Vicarage Road, now Vicarage Grove, was replaced a while back by a big modern housing development. Yes, it would now be in Southwark, not Lambeth; this is one of our occasional forays into neighbouring territory.

THE BLUE CARBUNCLE

The Blue Carbuncle: The ninth chronicle of Sherlock Holmes

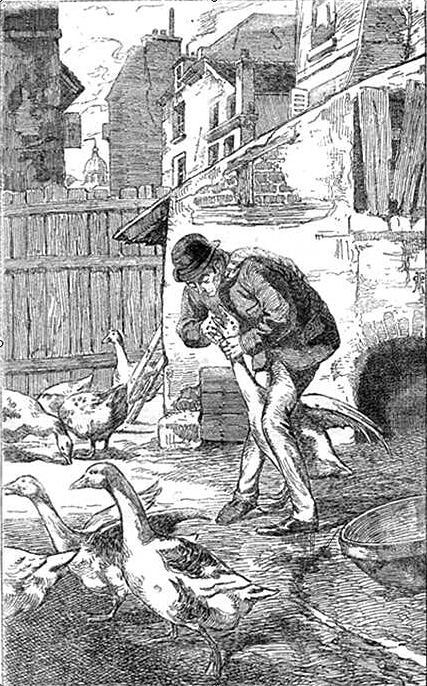

The Countess of Morcar’s famous jewel, the Blue Carbuncle, stolen from her suite at the Hotel Cosmopolitan, has been found – inside a Christmas goose. Holmes and Watson have traced the bird as far as the poultry dealer who sold it to the landlord of a public house near the British Museum – but he refuses to tell them who his supplier was.

“I have no connection with any other people who have been making inquiries,” said Holmes carelessly. “If you won’t tell us the bet is off, that is all. But I’m always ready to back my opinion on a matter of fowls, and I have a fiver on it that the bird I ate is country bred.”

“Well, then, you’ve lost your fiver, for it’s town bred,” snapped the salesman.

“It’s nothing of the kind.”

“D’you think you know more about fowls than I, who have handled them ever since I was a nipper? I tell you, all those birds that went to the Alpha were town bred.”

“It’s merely taking your money, for I know that I am right. But I’ll have a sovereign on with you, just to teach you not to be obstinate.”

The salesman chuckled grimly. “Bring me the books, Bill,” said he.

The small boy brought round a small thin volume and a great greasy-backed one, laying them out together beneath the hanging lamp.

“Now then, Mr. Cocksure,” said the salesman, “I thought that I was out of geese, but before I finish you’ll find that there is still one left in my shop. You see this little book? That’s the list of the folk from whom I buy. Here on this page is a list of my town suppliers. Now, look at that third name. Just read it out to me.”

“Mrs. Oakshott, 117, Brixton Road — 249,” read Holmes.

“Quite so. Now turn that up in the ledger.”

Holmes turned to the page indicated. “Here you are, ‘Mrs. Oakshott, 117, Brixton Road, egg and poultry supplier.’”

117 Brixton Road, where Mrs Oakshott bred geese

Map showing Baker Street, parallel to Vassall Road

“Now, then, what’s the last entry?”

“‘December 22d. Twenty-four geese at 7s. 6d. Sold to Mr. Windigate of the Alpha, at 12s.’”

Sherlock Holmes looked deeply chagrined. He drew a sovereign from his pocket and threw it down upon the slab, turning away with the air of a man whose disgust is too deep for words. A few yards off he stopped under a lamp-post and laughed in the hearty, noiseless fashion which was peculiar to him.

“When you see a man with whiskers of that cut and the ‘Pink ’un’ protruding out of his pocket, you can always draw him by a bet,” said he.

117 Brixton Road was and is a real address, the first house of thirteen in what was originally called Minerva Terrace – and at the time, as you may be able to see on this 1897 map, alongside it was … Baker Street! The terrace is still there, though Baker Street, Brixton is not.

WATERLOO STATION

Waterloo Station features in “The Speckled Band” and five other cases

Holmes and Watson were famous travellers, and they are recorded as using eight of the historic London railway stations. Rather surprisingly, they go just once from King’s Cross and not at all from St Pancras, but we know that they used Waterloo at least four times. John Openshaw, in the case of the Five Orange Pips, took a train from Horsham to Waterloo, and it was at Waterloo that Sir Henry Baskerville arrived in London.

The station developed in an unplanned way, each extension, each new set of platforms, being “temporary”, until the London & South-Western Railway finally decided on total reconstruction. Building began in 1904 and Waterloo Station as we know it was completed in 1922, just in time to be handed over to the new Southern Railway. This photograph was taken, I think, in about 1912.

THE BERYL CORONET

The Beryl Coronet: the thirteenth chronicle of Sherlock Holmes

This adventure begins with the arrival of a desperately troubled client.

“My name,” said our visitor, “is probably familiar to your ears. I am Alexander Holder, of the banking firm of Holder & Stevenson, of Threadneedle Street.”

The name [says Watson] was indeed well known to us as belonging to the senior partner in the second largest private banking concern in the City of London.

Mr Holder’s problem is too complex to summarise here. It’s enough that Holmes and Watson agree to go with him to his house in Streatham and, as Holmes puts it, “devote an hour to glancing a little more closely into details.”

This particular story has been investigated by a prolific local historian, John W Brown, whose booklet Sherlock Holmes in Streatham is probably definitive.

Noting that the date is almost certainly February 1886, he says:

“In the last two decades of the 19th century Streatham was a prosperous and highly desirable residential area. It contained a wide-variety of large, recently-built, handsome houses and its then semi-rural location, with excellent train links to London, made it a much sought after place for members of the aspiring middle classes to live.”

Dr and Mrs Conan Doyle set out on their tandem tricycle

Arthur Conan Doyle and his wife used to venture out from their house in Norwood on their tandem tricycle, and Mr Brown very reasonably assumes that they came to be quite familiar with Streatham.

Now, we know what Alexander Holder’s house, Fairbank, looked like:

… a good-sized square house of white stone, standing back a little from the road. A double carriage-sweep stretched down in front to two large iron gates. On the right side was a small wooden thicket, which led into a narrow path between two neat hedges stretching from the road to the kitchen door, and forming the tradesmen’s entrance. On the left ran a lane which led to the stables.

We also know that it was not very far from the station. But which station? There were three: Streatham, Streatham Hill and Streatham Common.

Leigham Court House, Streatham

Streatham Hill Station is convenient for Leigham Court Road, which was just the sort of area that a wealthy banker might choose. Former residents include Queen Victoria’s Solicitor, the Physician-in-Ordinary to Princess Beatrice, the publisher of the Church Times, the Master of Dulwich College, and two MPs.

However, Mr Brown suggests that if Alexander Holder’s house was in the Streatham Hill area, then Dr Watson would have said so. His candidate for Fairbank is Streatham Lodge, just a short walk from both Streatham and Streatham Common stations. Sadly, the house was demolished around the turn of the turn of the century, and no photographs or drawings are known to exist.

Streatham Lodge (“Fairbank”): “the modest residence of the great financier”

Streatham Lodge does not appear to have been a “modest residence” by today’s standards, but it was notably smaller than others in the area, such as Leigham Court House or Park Hill, so Watson’s description of it as a “modest residence” for a “great financier” may have been justified. But Mr Brown’s trump card is the fact that Streatham Lodge was the residence of William Matthew Coulthurst, senior partner in Coutts & Co, one of the largest private banks in England, and bankers to Queen Victoria and many members of the Royal family. A fair match for the senior partner in the second largest private banking concern in the City of London.

THE GREEK INTERPRETER

The Greek Interpreter: The twenty-fourth chronicle of Sherlock Holmes

Mr Melas, the interpreter, is introduced to Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson by the detective’s brother, Mycroft, who has rooms in the same house in Pall Mall.

Two days earlier, Mr Melas was hired for an apparently ordinary job that turned out to be quite extraordinary. He was taken at night in a closed carriage to an unknown destination and forced to interrogate a man whom he describes as deadly pale and terribly emaciated, his face grotesquely criss-crossed with sticking-plaster, and one large pad of it fastened over his mouth. This horrible charade over, Mr Melas was hurried out of the house and into the carriage. He tells Holmes and Watson:

“In silence we again drove for an interminable distance with the windows raised, until at last, just after midnight, the carriage pulled up.

“‘You will get down here, Mr. Melas,’ said my companion. ‘Any attempt upon your part to follow the carriage can only end in injury to yourself.’

“He opened the door as he spoke, and I had hardly time to spring out when the coachman lashed the horse and the carriage rattled away. I looked around me in astonishment. I was on some sort of a heathy common mottled over with dark clumps of furze-bushes. Far away stretched a line of houses, with a light here and there in the upper windows. On the other side I saw the red signal-lamps of a railway.

“The carriage which had brought me was already out of sight. I stood gazing round and wondering where on earth I might be, when I saw someone coming towards me in the darkness. As he came up to me I made out that he was a railway porter.

“‘Can you tell me what place this is?’ I asked.

“‘Wandsworth Common,’ said he.

“‘Can I get a train into town?’

“‘If you walk on a mile or so to Clapham Junction,’ said he, ‘you’ll just be in time for the last to Victoria.’”

Wandsworth Common was then, of course, in the parish of Wandsworth, and Clapham Junction was within the parish of Battersea. Both are now in the London Borough of Wandsworth, though Clapham, or most of it, is in Lambeth. The misleading name of the railway station was chosen because Clapham itself, which is about a mile away, was more fashionable than Battersea. This is the sort of game that estate agents enjoy playing.

Mycroft Holmes actually takes an active role in this case, to the extent that he places an advertisement in the newspapers – and a little later he is able to tell his brother that he has received a response – from Lower Brixton.

And that raises the question: where is “Lower Brixton”? Outside of the chronicles of Sherlock Holmes, I have found just one use of that name, in a book called The Brighton Road: The Classic Highway to the South, published in 1892. The author, Charles G Harper, says:

The Brighton Road by Charles Harper

“There is little in the Lower Brixton Road that is reminiscent of the Regency, but a very great deal of early suburban comfort evident in the old mansions of the Rise and the Hill, built in days when by a ‘suburban villa’ you did not mean a cheap house in a cheap suburban road, but a ‘commodious residence situate in its own ornamental grounds, replete with every convenience’, or something in that eloquent style. For when you ascend gradually, past the Bon Marché, and come to the hill-top, you leave for a while the shops and the continuous conjoined houses, and arrive, past the transitional stage of semi-detachedness, at the wholly blest condition of splendid isolation in the rear of fences and carriage-entrances, with gentility-balls on the gate-posts, a circular lawn in front of the house, and perhaps even a stone dog on either side of the doorway!”

I have read and re-read the relevant pages, and I cannot decide whether by “the Lower Brixton Road” Charles Harper means the lower-lying stretch north of the Bon Marché or the more elevated southern section comprising Brixton Rise and Brixton Hill.

THE NAVAL TREATY

The treaty in question is stolen from the office where Watson’s old school-fellow Percy Phelps has been working on it. The obvious – and, of course, wrong – suspect is the charwoman, Mrs Tangey, whose husband is a commissionaire at the Foreign Office. They live at no. 16, Ivy Lane, Brixton.

In 1982, the late Vernon Goslin wrote: “I remember Ivy Lane in my boyhood, a narrow alley off Brixton Hill, nearly opposite the Prison.”

THE NORWOOD BUILDER

From our point of view, “The Norwood Builder” is a really frustrating case. The builder, Jonas Oldacre, is said to live in Lower Norwood – now called West Norwood – which is firmly within the London Borough of Lambeth, but his house is “at the Sydenham end of the road of that name”, and that, by my reckoning, puts him in Lower Sydenham, which is in the London Borough of Lewisham. The other places that feature are Anerley in the London Borough of Bromley, and Blackheath, which is partly in Lewisham and partly in Greenwich.

BLACK PETER

“Black Peter” is another story of only marginal interest. Captain Peter Carey is murdered at his home near Forest Row in Sussex, and apart from that the drama is played out at 221B Baker Street. But we learn that Inspector Stanley Hopkins of Scotland Yard lives at no. 46 Lord Street, Brixton.

There is no Lord Street in Brixton.

THE SIX NAPOLEONS

The Six Napoleons: The thirty-fifth chronicle of Sherlock Holmes

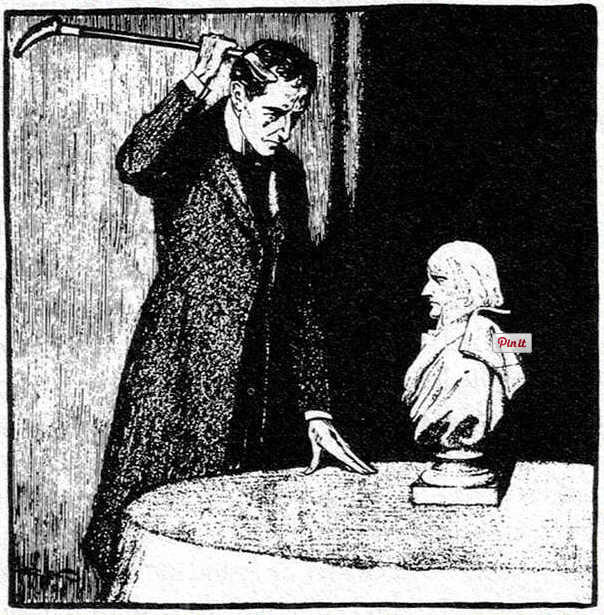

The case of the Six Napoleons brings us firmly back to Lambeth. “You wouldn’t think,” says Inspector Lestrade, “there was anyone living at this time of day who had such a hatred of Napoleon the First that he would break any image of him that he could see. But then, when the man commits burglary in order to break images which are not his own, that brings it away from the doctor and on to the policeman.”

Lestrade took out his official notebook and refreshed his memory from its pages.

“The first case reported was four days ago,” said he. It was at the shop of Morse Hudson, who has a place for the sale of pictures and statues in the Kennington Road.

No 310-312 Kennington Road, former premises of Morse Hudson’s shop. Identified by Bernard Davies. Photographed in 2007.

“The assistant had left the front shop for an instant, when he heard a crash, and hurrying in he found a plaster bust of Napoleon, which stood with several other works of art upon the counter, lying shivered into fragments. He rushed out into the road, but, although several passers-by declared that they had noticed a man run out of the shop, he could neither see anyone nor could he find any means of identifying the rascal. It seemed to be one of those senseless acts of Hooliganism which occur from time to time, and it was reported to the constable on the beat as such. The plaster cast was not worth more than a few shillings, and the whole affair appeared to be too childish for any particular investigation.”

“The second case, however, was more serious, and also more singular. It occurred only last night.

“In Kennington Road, and within a few hundred yards of Morse Hudson’s shop, there lives a well-known medical practitioner, named Dr. Barnicot, who has one of the largest practices upon the south side of the Thames.

Mountford Place, Kennington Road. One of these may have been Dr Barnicot’s house

“His residence and principal consulting-room is at Kennington Road, but he has a branch surgery and dispensary at Lower Brixton Road, two miles away. This Dr. Barnicot is an enthusiastic admirer of Napoleon, and his house is full of books, pictures, and relics of the French Emperor. Some little time ago he purchased from Morse Hudson two duplicate plaster casts of the famous head of Napoleon by the French sculptor, Devine. One of these he placed in his hall in the house at Kennington Road, and the other on the mantelpiece of the surgery at Lower Brixton. Well, when Dr. Barnicot came down this morning he was astonished to find that his house had been burgled during the night, but that nothing had been taken save the plaster head from the hall. It had been carried out and had been dashed savagely against the garden wall, under which its splintered fragments were discovered.”

Holmes rubbed his hands. “This is certainly very novel,” said he.

“I thought it would please you. But I have not got to the end yet. Dr. Barnicot was due at his surgery at twelve o’clock, and you can imagine his amazement when, on arriving there, he found that the window had been opened in the night, and that the broken pieces of his second bust were strewn all over the room. It had been smashed to atoms where it stood. In neither case were there any signs which could give us a clue as to the criminal or lunatic who had done the mischief. Now, Mr. Holmes, you have got the facts.”

And if you want to find out who the criminal or lunatic was, and what was the method in his madness, then read the story.

THE DISAPPEARANCE OF LADY FRANCES CARFAX

The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax: The forty-sixth chronicle of Sherlock Holmes

“Ah, what has happened to the Lady Frances?” [says Sherlock Holmes] “Is she alive or dead? There is our problem. She is a lady of precise habits, and for four years it has been her invariable custom to write every second week to Miss Dobney, her old governess, who has long retired and lives in Camberwell. It is this Miss Dobney who has consulted me. Nearly five weeks have passed without a word. The last letter was from the Hotel National at Lausanne. Lady Frances seems to have left there and given no address. The family are anxious, and as they are exceedingly wealthy no sum will be spared if we can clear the matter up.”

Camberwell, as so often, is a red herring, a will o’ the wisp. But stay with me, please. At Holmes’s request, Watson traces the missing lady’s movements, from Lausanne to Baden-Baden, where, he says:

Lady Frances had stayed at the Englischer Hof for a fortnight. While there she had made the acquaintance of a Dr. Shlessinger and his wife, a missionary from South America. Like most lonely ladies, Lady Frances found her comfort and occupation in religion. Dr. Shlessinger’s remarkable personality, his wholehearted devotion, and the fact that he was recovering from a disease contracted in the exercise of his apostolic duties affected her deeply. She had helped Mrs. Shlessinger in the nursing of the convalescent saint. He spent his day, as the manager described it to me, upon a lounge-chair on the veranda, with an attendant lady upon either side of him. Finally, having improved much in health, he and his wife had returned to London, and Lady Frances had started thither in their company. This was just three weeks before, and the manager had heard nothing since.

Holmes recognises the missionary as a ruthless confidence trickster known as “Holy Peters”. Back in London, the missing lady’s former suitor, Philip Green, has put himself at the detective’s disposal and has identified the supposed “Mrs Shlessinger” and followed her from a pawnbroker’s in Westminster Bridge Road. He tells Holmes and Watson:

“She walked up the Kennington Road, and I kept behind her. Presently she went into a shop. Mr. Holmes, it was an undertaker’s.”

My companion started. “Well?” he asked.

“She was talking to the woman behind the counter. I entered as well. ‘It is late,’ I heard her say. The woman was excusing herself. ‘It took longer, being out of the ordinary.’ They both stopped and looked at me, so I asked some question and then left the shop.

“The woman came out. Then she called a cab and got in. I was lucky enough to get another and so to follow her. She got down at last at No. 36, Poultney Square, Brixton. I drove past, left my cab at the corner of the square, and watched the house.”

There was then, I think, only one residential square in Brixton: Trinity Square, now called Trinity Gardens.

Trinity Gardens (“Poultney Square”), Brixton. One of these houses was the residence of “Dr Shlessinger”, known to the police as Holy Peters

True, Watson later describes no. 36 as “…a great dark house in the centre of Poultney Square”, and there have never been any buildings in the middle of Trinity Gardens, but I am not aware of any London square that surrounds a single residential building.

John Weber, whose researches have proved invaluable in this case, identifies the house as one of the two in the centre of the north side.

It’s that conversation at the undertakers’, of course, that takes Holmes and Watson to Poultney Square. Arriving in time to see the unusual coffin delivered, they enter the house and insist on seeing the body inside it. To their surprise and relief it is not that of the still beautiful Lady Frances. Instead it’s the withered, emaciated figure of a very old woman.

“Ah, you’ve blundered badly for once, Mr. Sherlock Holmes,” said Peters, who had followed us into the room.

“Who is this dead woman?”

“Well, if you really must know, she is an old nurse of my wife’s, Rose Spender by name, whom we found in the Brixton Workhouse Infirmary. We brought her round here, called in Dr. Horsom, of 13 Firbank Villas and had her carefully tended, as Christian folk should. On the third day she died — certificate says senile decay. We ordered her funeral to be carried out by Stimson and Co., of the Kennington Road, who will bury her at eight o’clock to-morrow morning.”

Lambeth Workhouse (“Brixton Workhouse”)

There was no workhouse in Brixton. The nearest were in Camberwell and Lambeth, and the latter did have an infirmary.

However, John Weber suggests that the unfortunate Rose Spender had actually been living at the Trinity Asylum for Aged Persons, conveniently situated in Acre Lane, just a stone’s throw from Trinity Square – which was in fact named after it.

I am not, I confess, convinced. The Asylum – which is still there, and is now understandably called Trinity Homes – was founded and endowed in 1824 by Thomas Bayley for “twelve poor women who professed belief in the Holy Trinity”. In other words it was and is an almshouse, and that is something very different from a workhouse.

Trinity Homes, former Trinity Asylum

Trinity Homes still, apparently, provides, as it has done for nearly 200 years, separate dwellings for elderly women.

But I am sure that Rose Spender was taken from the Lambeth Workhouse infirmary when she was already within days of dying, and she may well have been helped on her way to the grave.

Many of the workhouse buildings are still standing, and the Master’s House, rather wonderfully, is now home to the Cinema Museum.

John Weber adds: “‘13 Firbank Villas,’ the home of Dr Horsom, the attending physician at the ‘Brixton Workhouse Infirmary’ also never existed. The nearest we can come is Firbank Road, but this was located in Peckham, and is probably not a contender.”

Actually, with apologies to Mr Weber, we are not told that Dr Horsom was attached to the workhouse. What we are told is that Peters and his wife called him in to examine the old woman once they had brought her to their own house. He may have been a confederate of theirs, or a dupe. In any case, Firbank Road is only about two and a half miles from Trinity Square. I see no reason to rule it out.

Finally for this case, Bernard Davies identified no. 345 Kennington Road as the site of the undertaker’s.

The premises in Kennington Road formerly occupied by Stimson & Co., undertakers. Identified by Bernard Davies . Photographed in 2007.

It was boarded up when I took the photograph in 2007, and it was boarded up when I passed by a year or so ago.

THE VEILED LODGER

The Veiled Lodger: the fifty-ninth chronicle of Sherlock Holmes

The last case we have to consider, and that only briefly, is the sad business of the veiled lodger, the last but one of the stories written by Arthur Conan Doyle and published in The Strand Magazine, where it appeared in the issue for February 1927. Dr Watson records:

One forenoon — it was late in 1896 — I received a hurried note from Holmes asking for my attendance. When I arrived I found him seated in a smoke-laden atmosphere, with an elderly, motherly woman of the buxom landlady type in the corresponding chair in front of him.

“This is Mrs. Merrilow, of South Brixton,” said my friend with a wave of the hand. “Mrs. Merrilow does not object to tobacco, Watson, if you wish to indulge your filthy habits. Mrs. Merrilow has an interesting story to tell which may well lead to further developments in which your presence may be useful.”

Having heard her story and discussed it, Holmes and Watson set out for Brixton.

When our hansom deposited us at the house of Mrs. Merrilow, we found that plump lady blocking up the open door of her humble but retired abode. It was very clear that her chief preoccupation was lest she should lose a valuable lodger, and she implored us, before showing us up, to say and do nothing which could lead to so undesirable an end. Then, having reassured her, we followed her up the straight, badly carpeted staircase and were shown into the room of the mysterious lodger.

In the Summer 1982 issue of The Sherlock Holmes Journal, Vernon Goslin wrote: “As a teenager in 1927, I can recall buying The Strand Magazine in the Spring of that year, when the story first appeared, and how thrilled I was to identify our house in Fairmount Road, South Brixton, with the one described in ‘The Veiled Lodger’!”

Not exactly scholarship, but interesting!

So, that’s all there is to say about Sherlock Holmes and Lambeth. Isn’t it?

Well, no.

Sherlock Holmes was the master detective. So when, in 1892, Arthur Conan Doyle decided to kill off his creation – because, as he wrote to his mother, “He takes my mind from better things” – he created a master criminal to be the agent of death: ex-Professor James Moriarty, whom Holmes calls “the Napoleon of crime”.

Scholars have identified several historical persons as probable influences on the character, including the astronomer Simon Newcomb, the mathematicians Carl Friedrich Gauss and George Boole, and the 18th century “Thief-taker General” Jonathan Wild, described by Holmes as “the hidden force of the London criminals, to whom he sold his brains and his organization on a fifteen per cent. commission.”

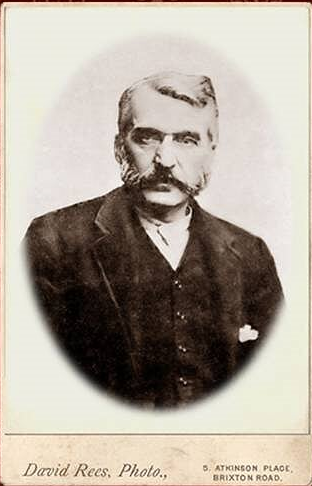

And there was Adam Worth.

Adam Worth, the “Napoleon of the criminal world”

Western Lodge, Clapham Common

Worth, alias Henry Raymond, was born in Germany, grew up in America, and served in the Union Army during the Civil War. He was recovering from wounds sustained at the second Battle of Bull Run when he learned that he was officially listed as killed in action. He left the hospital and embarked on a curious and wide-ranging criminal career. In 1873 he moved to England, where he expanded his organisation, and two years later he bought a rather nice house overlooking Clapham Common. Today Western Lodge is in that sliver of Clapham that’s within the London Borough of Wandsworth, but only by a matter of yards. (Sherlock Holmes famously said that there is nothing so important as trifles, but in this case, I think, the old legal maxim applies: De minimis non curat lex.) It was while he was living here that Worth stole Gainsborough’s portrait of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire from Agnew’s of Bond Street. (He later sold it back to Agnew’s.) He died in 1902 and was buried in a mass grave at Highgate Cemetery. In 1997 a gravestone was erected by the Jewish-American Society for Historic Preservation. The epitaph reads: Adam Worth, a.k.a. Henry J Raymond – “The Napoleon of Crime”.

It was Sir Robert Anderson, head of the CID at Scotland from 1888 to 1901, who gave him that title – or, to be exact, he called Worth “the Napoleon of the criminal world”. But he did so in 1907, fifteen years after Professor Moriarty was created as the nemesis of Sherlock Holmes.

And there are other Holmesian connections.

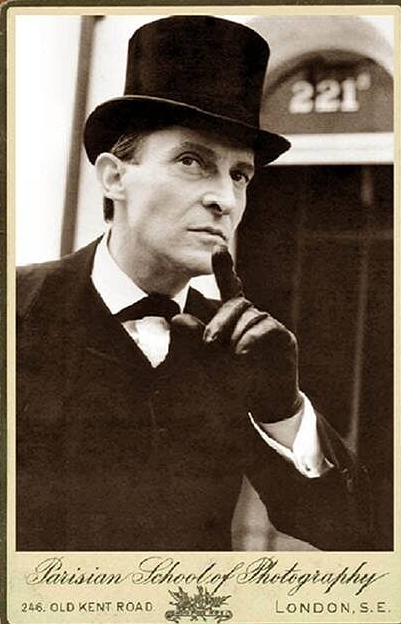

Jeremy Brett: distinguished resident of Clapham Common

Jeremy Brett played the detective on television for ten years and on stage for a year. It’s no exaggeration to say that, for the last quarter of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st, he was the Sherlock Holmes. His last home was a penthouse flat at no. 47 Clapham Common North Side, one of two very handsome apartment blocks, built in the French style of the Second Empire, on either side of Cedars Road, and originally known as The Cedars. Friends who visited the flat report that the view south over the Common is glorious.

The boundary between The London Boroughs of Lambeth and Wandsworth runs north along Wix’s Lane, just to the west of Cedars Road and parallel with it. And that, of course, means that Sherlock Holmes – or rather, the actor identified with him – actually lived in Lambeth, by a matter of a hundred yards or so.

Clapham Common, Northside

Finally, another even more famous name.

Charlie Chaplin, understandably, merits no fewer than three commemorative plaques in south London, two of them in Kennington – which is to say, in Lambeth.

But what has the great star of silent comedy to do with the great detective?

After the hugely successful London run of his play Sherlock Holmes at the Lyceum Theatre, the actor and dramatist William Gillette returned to America, while two companies toured Britain with the play. They were led by Julian Royce and H A Saintsbury, and it was Saintsbury who cast the eleven-year-old Charles Chaplin in the important role of Billy the page boy.

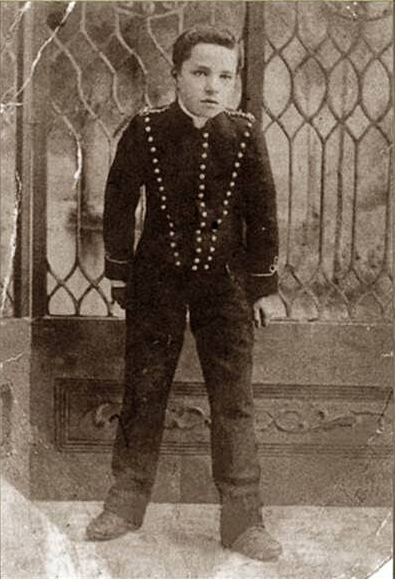

Master Charles Chaplin as Billy the page in William Gillette’s famous play “Sherlock Holmes”, c. 1903

In 1905 Gillette came back to London with a new play, Clarice, and a short curtain-raiser called The Painful Predicament of Sherlock Holmes, in which he again cast young Chaplin as Billy. Clarice was not the success that he had hoped for, so, for the remaining six weeks of his lease on the Duke of York’s Theatre, audiences were treated to a revival of Sherlock Holmes, with William Gillette in the role that he had written for himself, and Charles Chaplin as Billy the page.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, really is that. Thank you for accompanying Sherlock Holmes, Dr Watson and me on our Lambeth Walk!

Roger Johnson

Editor: The Sherlock Holmes Journal

The Sherlock Holmes Society of London

www.sherlock-holmes.org.uk

Bibliography

DAVIES, Bernard: Holmes and Watson Country – Travels in Search of Solutions (The Sherlock Holmes Society of London, 2008)

BROWN, John W: Sherlock Holmes in Streatham (Streatham: Local History Publications, 1993)

WEBER, John E: Under the Darkling Sky – A Chrono-Geographic Odyssey Through the Holmesian Canon (Eugenia, ON, Canada: The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2010)