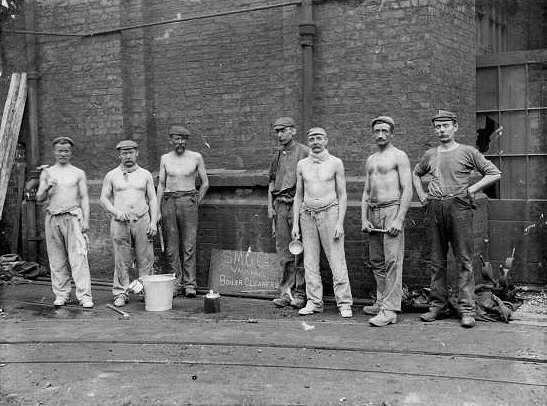

Boiler cleaners at the South Metropolitan Gas Works, South Lambeth

Practical use of gas was first demonstrated by William Murdock in 1792. He developed production techniques, which made commercial use practicable by 1802. In 1814 coal gas was first used for street lighting in Westminster to help prevent crime. The first gas street lamps used a simple (non-aerated) jet, which gave a poor light and were very smoky. Aerated burners, which were brighter, were introduced in the 1840s. But it was only in 1885 that Auer’s incandescent gas-mantle was patented which produced a genuinely bright light. (Welsbach, Frederick Carl Auer, Baron von Welsbach [1858-1929] had discovered that a finely woven mesh, impregnated with the two rare earth elements when heated in a gas flame would glow white hot so giving a very much brighter whiter light than just using a gas jet alone.)

There were gasworks at Nine Elms near the site of Battersea Power Station. In 1837 the coal yard at the gas works was one of the first structures in the world to make use of H.R. Palmer’s corrugated iron sheet roofing. The coal yard was probably open-sided with a barrel-vaulted roof of curved corrugated iron sheets riveted together with additional tie rods for lateral stability.

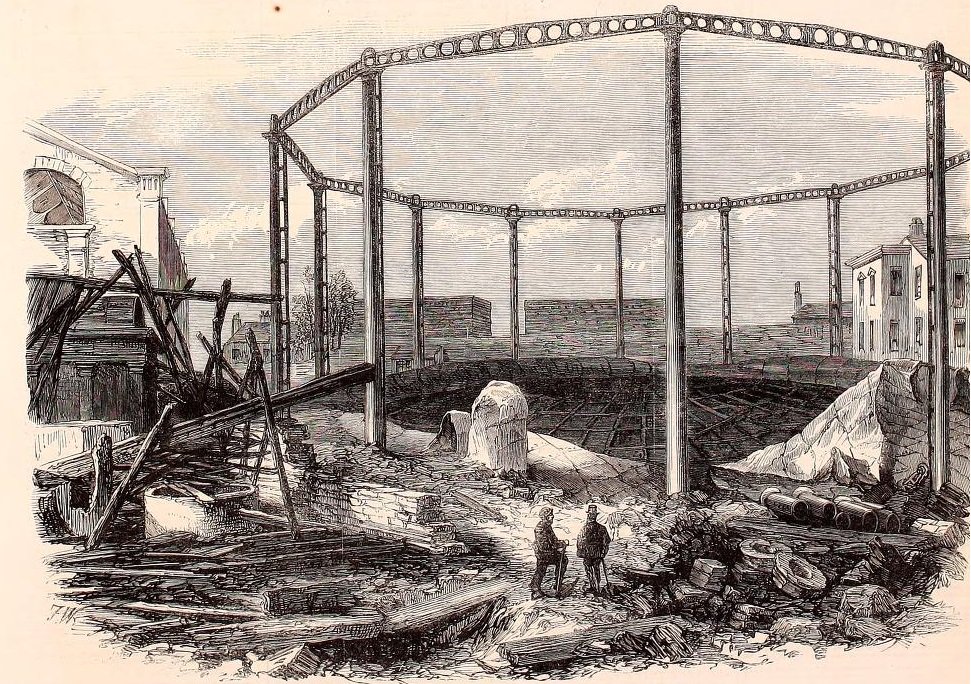

The gas explosion at Nine Elms

The Fatal Gas Explosion at Nine Elms

On the last day of October 1865 there was a major disaster at the London Gaslight Company works at Nine Elms. The site had two gasholders each holding about a million cubic feet of gas. One of these exploded and was completely destroyed, sending large chunks of ironwork and masonry far and wide. The other holder caught fire sending a huge jet of flame into the sky but did not explode.

Several nearby buildings, including residential houses, were badly damaged by the blast and about thirty casualties were taken from these buildings. Seven men were killed outright with three more dying in St Thomas’ Hospital. Many of the survivors were very badly burned and had received servere blast injuries.

The exact cause of the explosion is not known but most of the fatalities were from maintenance staff working in the nearby Meter House. This building contained equipment that controlled the gas supply going through parts of the plant. Part of this equipment consisted of cone shaped gasholders that were sealed by immersion with water. One likely scenario is that one of the maintenance workers stood on one of these regulating gasholders so displacing the water and breaking the seal which allowed a large quantity of gas to escape and be ignited either by a stray spark or more likely by someone illegally smoking (the only survivor of the maintenance gang had left the building to get a pipe of tobacco). This blast then triggered the explosion in the connected gasholder.

Other local gas companies quickly stepped in to help maintain gas pressure and the second gasholder was repaired and was operational within two days. A new gasholder on the site was already under construction at the time of the explosion and this was completed ahead of schedule.

The names of those who died on site were:

Frank Woodhams, Plasterer, aged 19

William Carter, Carpenter, aged 24

John Dwyer, Plasterer’s boy, aged 16

John Fielder, Carpenter, aged 31

Frederick Dove Thomsett, Brickwork Sub Contractor, aged 39

Thomas O’Donnell, Plasterer, aged 29

Edward Burke, Plasterer, aged 23

The following casualties died in St Thomas’ Hospital:

William Sidney Smith, Assistant Forman Stoker (age not known)

Patrick Shea, Labourer, aged about 60

John Robert Cox, Gas Refiner, aged 54

Gas works accidents

Accidents were extremely common. For example, Jenny Crawford wrote to the Vauxhall Society in January 2011 to tell us about her great-grandfather, John Fullick of 76 Borough Road, who died on 4 February 1920 at the Metropolitan Gas Works in Vauxhall. The 63-year-old fireraker was, according to his death certificate, “crushed between light engine and railway arch at Gas Works”. He left a wife and three young children. (Note: Jenny also provided irrelevant (in this context) but interesting information about Fullick’s marital status: he had bigamously married Ada Castle, stating he was a widower. In fact his legitimate wife was still alive but had left him years previously to live next door with a fish hawker named Henry Heather.) Colourful details of this nature give the lie to the myth that the lives of people in “olden times” were necessarily more ordered and respectable than our own.