By Sarah Bridger

Henry Fawcett

A terracotta statue of Henry Fawcett, which was unveiled on Wednesday 7th June 1893 by the Archbishop of Canterbury in Vauxhall Park, mysteriously vanished in late 1959.[1] It was designed by the celebrated Victorian sculptor George Tinworth, and donated by Sir Henry Doulton. The statue has not had a confirmed sighting since its disappearance, and its current condition and whereabouts is the subject of a number of myths. The statue was not only a memorial to the life and work of Henry Fawcett, but marked the site of his former home, which was demolished to create Vauxhall Park.

Henry Fawcett was an economist and politician who was held in high regard by the public. He was born in 1833 and educated at the University of Cambridge.[2] At the age of 25 he was involved in a shooting accident that left him blind. However, he refused to let his affliction dampen his life and ambitions. He rose to become a Professor in Economics at Cambridge University and was elected Member of Parliament for Brighton in 1865 to 1874, and subsequently for Hackney in 1874 to 1884. In 1880 he was also appointed the position of Her Majesty’s Postmaster-General.[3] He introduced improvements in the Post Office such as the parcel post, postal orders and sixpenny telegrams. He was also an avid supporter of women’s rights and encouraged the Post Office to employ women. He married the renowned suffragist, Millicent Fawcett, in 1867.

Both Henry and Millicent were also devoted to the cause of the poor and the preservation of commons and open spaces for public enjoyment, and it was whilst they were living at number 51 Lawn House in Vauxhall that this devotion turned closer to home. Lawn House, as it was so aptly named, came with a substantial garden in which the Fawcetts could relax and enjoy the open air in London. But they soon realised that due to the increasing industrial nature of Vauxhall in the 1880s, open land was rapidly disappearing. Two years after Henry’s death in 1886, Millicent and her friends, including Octavia Hill, campaigned for a park to be created on the site of Lawn House that could be dedicated to Henry’s memory.[4]

On obtaining permission from the Lambeth Vestry, Lawn House was demolished to make way for the Park. Octavia Hill, who is perhaps best known as one of the associated founders of the National Trust, was also the treasurer of the Kyrle Society at the time, which aimed to bring open spaces to the lives of the urban lower class. The Society paid for the park’s design, which was carried out by the landscape gardener Fanny. R. Wilkinson. The Victorian and Edwardian architect Charles Harrison Townsend designed the entrance gates and railings.[5] The park was officially opened by the Prince and Princess of Wales, the Duke of Edinburgh, who was also president of the Kyrle Society, and Princess Louise on Monday 7th July 1890.[6]

The statue of Henry Fawcett was not donated to the park until three years later in 1893, Fig.2. It had been privately commissioned by Sir Henry Doulton, the local ceramic and pottery factory owner, and modelled by the Victorian sculptor George Tinworth. It was made a short distance away from the park, at the Royal Doulton factory’s headquarters on Black Prince Road in Lambeth. The statue was suitably positioned on the site of the Fawcett’s former home. Speaking on that day, Henry Doulton commended the man and statue itself:

‘Henry Fawcett was one of the pioneers in the movement for the preservation of commons and open spaces, and worked hard in this when – as I know from personal experience – there was a strange apathy on this important subject, which I rejoice to say has given place to a jealous regard for public claims and rights. It seemed to me desirable to preserve in some lasting form the outward semblance of so remarkable a man, and that there was a special fitness in erecting the memorial on the site where his house stood, and in the midst of grounds set apart for the recreation of the people. The vestry of Lambeth, who are the custodians of Vauxhall Park, shared my views, and throughout have given their co-operation. To my friend George Tinworth, we are indebted for an interesting and successful example of his art.’[7]

Fig. 2. The Henry Fawcett Memorial situated in Vauxhall Park, by George Tinworth, 1893

The monument, including its case, rose to roughly sixteen feet high.[8] It was executed in terracotta, a material that had gained popularity in the last decades of the nineteenth century. Henry was depicted seated, in an ornate chair, wearing the academic robes of a Professor at the University of Cambridge.[9] He was about to be crowned with a wreath of laurels given from the figure of Victory, which was likely present to represent his victory over his affliction. The base contained eight separate bas-relief sculptures that depicted symbolic moments in Fawcett’s life and career. Depictions of courage and justice, two attributes that were well associated with him, were situated on the back and front of the base. Truth and sympathy were also located on the side panels. The remainder of the relief panels were more closely related to his career. His work within the Post Office was represented by a female Post Office clerk.[10] He was also championed for the reduction of the price of a telegram, which was depicted through the relay of good and bad news. The final panel portrayed India, which referenced his instrumental involvement in the appointment of committees to Indian finance, through which he became publically known as ‘Member for India’ in parliament.[11] His admiration was also echoed in the inscription, located on the front of the base, which was the same as the inscription on his memorial located in Westminster Abbey.[12]

‘…his inexorable fidelity to his convictions commanded the respect of statesmen. His chivalrous self-devotion to the cause of the poor and helpless won the affections of his countrymen and his fellow Indian subjects. His heroic acceptance of the calamity of blindness has left a memorable example of the power of a brave man to transmute loss into gain, and to wrest victory from misfortune.’

Fig. 3. George Tinworth working on the model of the statue of Henry Fawcett

Tinworth was employed at Doulton’s Lambeth factory for much of his working life. The majority of his sculpture consisted of terracotta relief panels, which often depicted religious scenes. Though the memorial included some of these typical relief panels, the subject, as well as the carved life-size figures, were a rare example of his varied sculptural ability. The memorial to Henry was one of only three men that George Tinworth is known to have modelled life-size figures on.[13]

The statue, unlike so much other public art, survived the World War Two bombing raids on London, only to disappear from the park ten years later in 1959. As stated, myths have grown around its disappearance. One story suggests that the memorial was dismantled and moved to Salisbury, Henry’s birthplace, yet no trace of it can be found.

The truth, however, is less romantic. Hidden in the Lambeth Council minutes, is a record from February 1959 that the Council approved the removal of the statue:

‘As the first stage of a suggested programme of works to be carried out during the next four years to provide additional grassed areas (in Vauxhall Park), we propose to remove the Henry Fawcett statue, the bandstand and its surrounding paved area, which are no longer required.'[14]

The Council, speaking to South London Press in February 1959, insisted that neither the bandstand nor the statue were appreciated. They claimed that to ‘knock down’ the statue and replace it with open space accompanied by a footpath would enhance the park.[15] The cost of removing the statue and the bandstand was five hundred and ninety pounds.[16]

The Council paid no heed to the memory of Henry Fawcett in the discussion of the memorials removal. Nor did they question its artistic value and symbolic position in the park as a marker of the site of the Fawcett’s former home, and all that Henry had done for the preservation of commons. The Council wholly underestimated the public enjoyment of the memorial. A few months after its removal, Charles Handley-Read wrote publicly of the loss in Country Life Magazine:

‘For I learn from the Borough Council concerned that the Fawcett monument has been removed from Vauxhall Park. It is difficult to believe that its removal was necessary… it is hoped that there were good reasons for depriving us of this rare example of Tinworth’s craftsmanship.'[17]

The memorial also appeared in the popular British film Look Back in Anger in 1959, which was based on John Osborne’s successful play. The discussion of the statue and its appearance in the film suggests that it was in fact the Council who did not appreciate it, and perhaps the cost of upkeeping it, rather than the general public or artistic community.

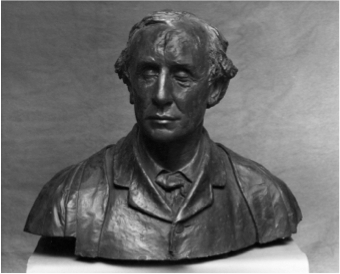

Another myth, which has perhaps gained the most popularity, tells us that the headmaster of the nearby Henry Fawcett Primary School was walking through the park whilst the statue was being demolished and salvaged the head to display in the school. However, on closer inspection, there are subtle differences between the head located in the school and that on the lost statue. Research into the school’s piece has revealed that while it does depict Henry Fawcett, it was modelled by another Victorian sculptor, Henry Richard Hope-Pinker, who also executed a statue of Henry that stands in Salisbury Market Place. The bust was originally a plaster cast that has since been bronzed and is an exact match to one held by the National Portrait Gallery, which was donated by Hope-Pinker in 1905, Fig. 4.[18]

Fig. 4. Henry Fawcett by Henry Richard Hope-Pinker, c.1878-1884

Hope-Pinker is known to have sculpted at least one other bust of Henry Fawcett, which was sold at auction in 2008.[19] He typically carved without a model, and preferred to work from life or from drawings. It could, therefore, not be at all coincidental that his bust of Henry bears a remarkable similarity to the photo of him seen in Fig. 1.

The careful phrasing in the Council minutes could lead one to believe that the memorial was simply ‘removed’ and rehoused. But given that the myths have proven to be false, and no part of the statue has been identified since its disappearance, it looks increasingly likely that it was completely knocked down in 1959 as the South London Press recorded. All that remains on the spot of the irreplaceable statue is a plaque that records the site as the Fawcett’s former home. Today, it would have undoubtedly been a celebrated public monument and a testament to George Tinworth’s artistic talent and use of terracotta. It would most likely have joined two other public statues that depict Henry Fawcett in Victoria Embankment Gardens in London, and Market Place in Salisbury, on English Heritage’s list of designated assets. It is sad that the Council at that time did not respect or care for the monument, resulting in its premature demise and depriving future generations the chance to appreciate its beauty. However, we should remember that, in many ways, the true memorial and lasting testament to both Fawcett and his legacy was never really the monument, but Vauxhall Park itself.

REFERENCES

- Terry Cavanagh, Public Sculpture of South London (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2007), p. 372.

- Leslie Stephen, Life of Henry Fawcett (London, Smith, Elder & Co, 1885), p. 20.

- Stephen, p. 409.

- Ross Davies, Vauxhall: A Little History (London: Nine Elms Press, 2009), p.48.

- Cavanagh, p. 373.

- ‘Opening of Vauxhall Park’, The London Illustrated News, 12 July 1890, p. 39.

- Cavanagh, p. 374.

- ‘Our Illustrated Notebook’, Magazine of Art, Vol 16, 1893, p. 180.

- ‘Memorial Statue of Mr. H. Fawcett’, Illustrated London News, 10 December 1892, p. 758.

- ‘Our Illustrated notebook’, p. 180.

- Stephen, pp. 341-401.

- ‘Our Illustrated notebook’, p. 180.

- Charles Handley-Read, p. 561.

- London, Lambeth Archives, Lambeth Council Minutes 1958-1959, MCB/CI/58, LVIII, p. 762.

- South London Press, 20 February 1959, clipping, page unknown.

- Lambeth Council Minutes, p. 762.

- Charles Handley-Read, p. 561.

- The National Portrait Gallery, Henry Fawcett (n.d.) [accessed 18February 2014]

- Arcadja Auction Results, Henry Linder (n.d.) [accessed 18 February 2014]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Cavanagh, Terry, Public Sculpture of South London (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2007)

Davies, Ross, Vauxhall: V. 1. : A Little History (London: Nine Elms Press, 2009)

Goose, Edmund, A Critical Essay on The Life and Works of George Tinworth (London: The Fine Art Society, 1883)

Stephen, Leslie, Life of Henry Fawcett (London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1885)

Articles and newspapers

Handley-Read, Charles, ‘Tinworth’s work for Doulton – II: Salt Cellars and Public Statues’, Country Life, 15 September 1960, pp. 560 – 561

‘Memorial Statue of Mr. H. Fawcett’, Illustrated London News, 10 December 1892, p. 758

‘Opening of Vauxhall Park’, The Illustrated London News, 12 July 1890, p. 39

Our Illustrated Notebook’, Magazine of Art, Vol 16, 1893, p. 180

‘Proposed Public Park at Vauxhall’, The Illustrated London News, 12 January 1889, p. 35

South London Press, 10 June 1893, p. 5

South London Press, 20 February 1959, clipping, page unknown.

Online sources

Arcadja Auctions Results, Henry Linder (n.d.) [accessed 18 February 2014]

Friends of West Norwood Cemetery, A Memorial to George Tinworth? (n.d.) [accessed 18 February 2014]

The British Postal Museum and Archive, Employment of Disabled People (2012) [accessed 18 February 2014]

The National Portrait Gallery, Henry Fawcett (n.d.) [accessed 18 February 2014]

Manuscripts

London, Lambeth Archives, Lambeth Council Minutes 1958 – 1959, MCB/CI/58, LVIII, p. 762