by David Coke

The history of the music of Vauxhall Gardens represents the development of a purely English style from the time of John Playford, John Blow and the early works of Henry Purcell, through to Felix Mendelssohn’s great oratorio Elijah. It can be argued that the pleasure gardens single-handedly fostered and maintained the English school of music at a period when it was under enormous pressure from European imports, and otherwise might have sunk without trace.

From the earliest times of the gardens, just after the Restoration, until their final closure in 1859, music was central to the entertainments available at Vauxhall Gardens. It developed from the popular requests played by buskers and strolling wind bands to the ‘monster concerts’ organised by Louis Jullien and Philippe Musard’s promenade concerts in Victorian times.

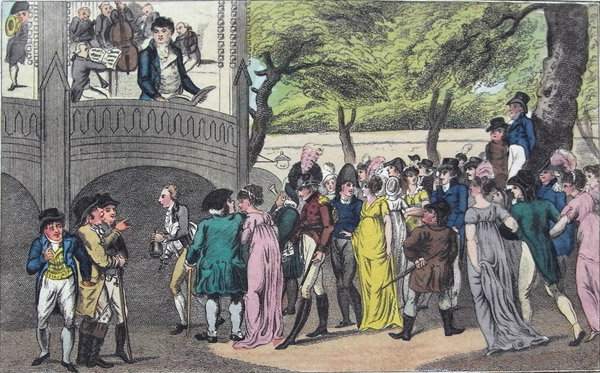

Syncopated pick-pocketry: this picture, from David Coke and Alan Borg’s Vauxhall Gardens: A History (Yale, 2011) is the headpiece to a song called ‘One Half of the World Don’t Know How t’Other Lives,’ which the popular tenor Charles Dignum performed at Vauxhall Gardens. The print, published by Laurie & Whittle in 1805, neatly represents the mixed audience for music at Vauxhall Gardens. There’s Mr Dignum singing in the famous bandstand (called ‘The Orchestra’), and so as far as the authors know, this also the only representation of a constant problem to the Vauxhall Gardens proprietors – a pickpocket at work in the crowd (see the group of three people, lower left). The print in itself may be a little light-fingered in that it is loosely based on a celebrated 1784 Rowlandson print of Vauxhall Gardens.

Between these extremes, Vauxhall Gardens provided a platform and a huge regular audience for London-based musicians and composers every summer for over a century. In the heyday of the gardens the compositions of G.F. Handel set the benchmark for the music presented every evening to Vauxhall’s visitors, and every evening there were at least a thousand people there to hear it; over the one hundred or so evenings of the summer season, more than 100,000 visitors would have heard the music, in some cases many times.

The new compositions of top composers like William Boyce, Thomas Arne, and Handel himself were always balanced by more popular military music, dances, and, after the mid 1740s, pastoral and patriotic ballads.

Vauxhall not only provided regular employment for London’s musicians, but also an insatiable market for new English music and song. Dozens of English composers and lyricists found regular work there, at a time when London theatre managers were falling over themselves to present the latest prodigies from Europe, and competing with each other over how expensive was each new performer.

Today, it is for songs like ‘Cherry Ripe’ and the ‘Lass of Richmond Hill’ that Vauxhall is justifiably remembered, but in fact its contribution to the development of British music is more profound than the addition of a few songs to the repertory. Vauxhall transformed the whole way that music was perceived by its audience. Because the music was performed usually in the open air, and because it was intended to engender an atmosphere of relaxed happiness, there was no pressure on the Vauxhall audience to enjoy it, or to react to it at all. In fact, most people tended to wander around the gardens during the instrumental music and only to crowd around the orchestra-stand to hear the songs, or ogle the singers. In this way, a large and very mixed audience came to accept all sorts of music as a normal part of an evening’s entertainment, and a balanced programme of high quality concertos, interspersed with marches, dance music, cantatas, catches & glees and popular songs became the standard fare of public concerts everywhere.

The music written by men like John Worgan, J.C. Bach, James Hook, and Henry Rowley Bishop for Vauxhall Gardens is not as well known today as it was to their contemporaries, but without it, composers like Arthur Sullivan, Edward Elgar and Ralph Vaughan Williams, not to mention the innumerable composers of modern popular songs, would have had a less secure foundation upon which to build their own later masterpieces.

David Coke