Planned changes to constituency boundaries bring into focus the perennial need to define the interfaces between blocks of land at every level – be it the garden fence or the Iron Curtain. In the distant past, with much lower populations and pressure on resources, boundaries were often ill-defined zones, rather than fixed lines, and in a pre-literate society remembered as part of oral tradition. In England, it is not until the mid-late Anglo-Saxon period (c.AD700-1066) that we find written records of land grants (“charters”), often with boundary clauses attached to them setting out in more or less detail a series of features demarcating an estate or manor from its neighbours in an increasingly fragmented landscape. Such boundary details survive for relatively few places in the London area, and Lambeth is fortunate in having one of these.

The land grant in question was one of a series in several counties to the newly-founded collegiate church at Waltham (Abbey) in the Lea Valley on the Essex/Middlesex border. This was founded c.1060 by Earl Harold Godwineson (later King Harold II, famously killed at the Battle of Hastings in 1066). The charter we have is in the form of a confirmation by Edward the Confessor dated 1062. Although surviving only in copies of the 13th century, and considered to be spurious or a fabrication by many scholars, the document contains boundary clauses for the various estates that indicate an Anglo-Saxon source.

Lambeth was originally a very large parish, extending from the Thames to Norwood, and may originally have been a single estate, probably in royal ownership. The Waltham grant provides the first concrete evidence of fragmentation, although we have no information about how it may have come into Earl Harold’s hands. The land in question represents the medieval manors of Vauxhall and Stockwell, although these names are not on record until 1279 and 1197, respectively (Vauxhall was granted to the eponymous Faulkes de Breauté c.1215). Stockwell means ‘well or spring by the tree trunk or stump’ (OE stocc, w[i]elle). The area lying within the boundaries discussed below comprises around 1,000 acres.

The estate had already been lost by the canons of Waltham when Domesday Book was compiled in 1086; they were victims of Harold’s spectacular downfall. The manor was then held by Robert Count of Mortain, a prominent Norman nobleman and half-brother of William the Conqueror. It was assessed at 6½ hides, an unusually precise figure that may reflect its two component parts, one of five, the other of 1½ hides. (The hide was originally the land to support on household, but by the late-11th century was an assessment, often arbitrary, related to taxation. These fiscal hides varied widely in area, and were not a fixed 120 acres as is frequently stated.)

Five hides was reckoned to be the minimum holding for a thegn, a middle-ranking landowner, and it is possible that the “Lambeth” estate granted by Harold was originally such a unit, onto which the odd 1½ hides had been grafted. Domesday Book offers one of its typically tantalising clues when it states under entry for Battersea manor that the ‘Count of Mortain holds 1½ hides of the lands of this manor; they were there before 1066, and for some time after.’ As the 1062 charter gives no hidage for “Lambeth”, the Domesday note under Battersea offers a solution to the odd assessment of Lambeth, the 1½ hides being double-counted. Subsequent sources offer no clue as to whether this land lay within the boundaries of Battersea, and had successfully been retrieved by Westminster Abbey, or if it lay in Lambeth and was lost permanently. On balance, the former seems more likely – Norman barons were notorious for seizing land in the aftermath of the Conquest. It seems best to assume that the “Lambeth” estate of 1062-86 was a five-hide centred on Stockwell, no doubt with a landing-place at what later became a separate entity called Vauxhall. It is intriguing that nearly a thousand years later, the Lambeth-Battersea boundary may be about to change again!

The Lambeth Charter of 1062

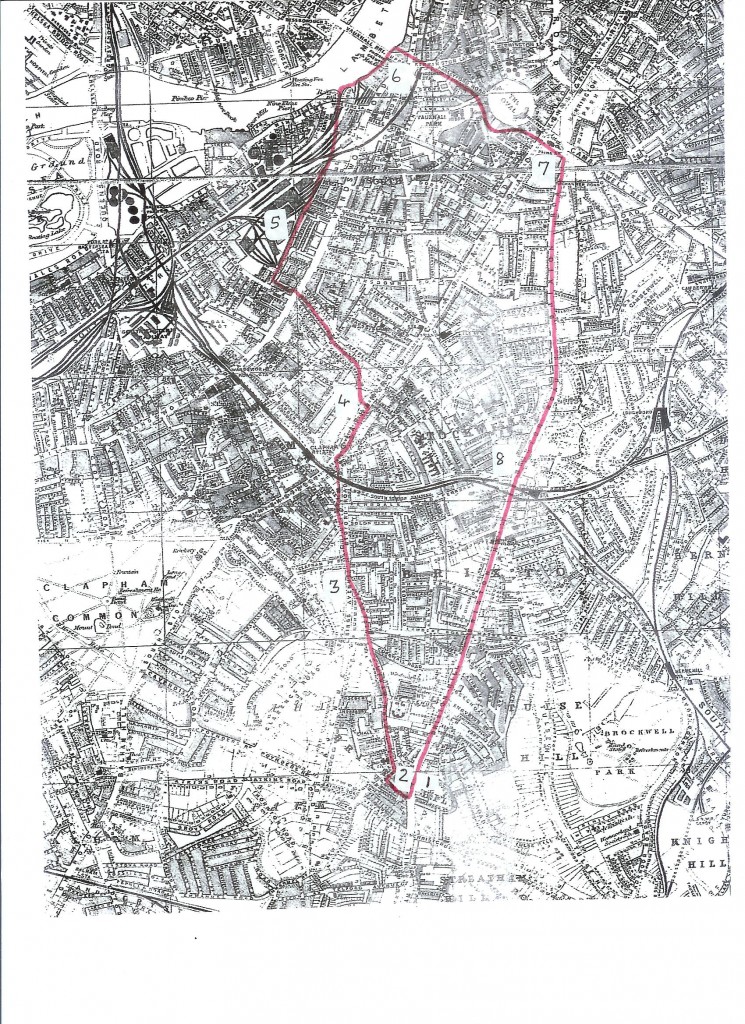

This boundary clause has relatively few points. The perambulation proceeds in the usual clockwise fashion (“with the sun”). Thus they are not as given in Michael Green’s Historic Clapham, which goes anti-clockwise and has some wrong identifications of boundary points, as well as mistranslations from the Old English (hereafter OE). The details are summarised below, with comments on modern locations where possible.

Þis synd þæt langemære into Lambehyð: These are the boundaries of Lambeth.

1 Ærest æt Brixges Stane: First at Beorhtsige’s Stone.

This is basis of the modern name Brixton. Originally to a Hundred, one of the large subdivisions within the county of Surrey from the 10th century to the 19th, it has become restricted to a small part of modern Lambeth. Hundred moots often met at landmarks such as barrows or stones. Some were prehistoric survivals. In this case the stone may possibly have been a Roman milestone, since Brixton Hill follows the Roman road between London and the south coast near Brighton, which gave its name to Streatham. The precise location of the stone is not known, but clearly lay near the summit of Brixton Hill where Lambeth and Clapham parishes meet, south of the prison.

2 Swa forð þurh thane graf: So forth through the grove (OE grāfa ‘grove, copse’, not græf ‘digging, grave’). This small patch of woodland would have been located in the vicinity of modern New Park Road.

3 To þam Mærdice: To the boundary ditch. This feature, wholly or partly man-made, forms the boundary between Lambeth and Clapham along modern Lyham Avenue, Bedford Road and Clapham Road. It may relate to the division of an earlier large estate extending west of Lambeth. Thirty hides were ascribed to Clapham in the late-9th century, but only ten by 1066.

4 Swa to Bulce treo: So to Bulca’s Tree. Isolated trees were often used as boundary marks, and some took their name from an adjacent landholder. The OE name Bulca is on record in Wiltshire in 778. Less likely is a derivation from OE bulluc, ‘bullock’. As is the way with ephemeral features, it is not clear where the tree lay. It was probably in the vicinity of Clapham Road, where the boundary turns north-westwards.

5 To Hyse: To Hese. OE hēse/hæse means brushwood or land overgrown with brushwood. This was apparently an extensive area in the vicinity of Nine Elms, extending into both Battersea and Lambeth. The name survived in Battersea well into the medieval period, apparently with a settlement of some kind, probably a hamlet (cf. Hayes in Middlesex and Kent).16

Strangely, the charter bounds make no mention of either the Thames or the River Effra, one or both of which would have been encountered if they followed the Lambeth parish boundary before turning east around the site of today’s Vauxhall Station. This may reflect the desire of the principal estate owner in the parish to retain the whole river frontage. The bounds then probably followed one or other of the streams that ran through the area south of the Oval, and one would have expected them to be featured, rather than the very specific marker used as point 6, but see below.

6 To Ælsyges hæcce: To Ælfsige’s gate or sluice. OE hæc[c] ‘hatch, gate, grating’ Ælfsige was probably a neighbouring landowner. One of the senses of hæc[c] is ‘sluice, floodgate’, which would fit the topography where the Effra flows into the Thames.

The boundary then follows the northern of the two Effra streams south of today’s Kennington Oval to the point where the two Roman roads joined (now Clapham and Brixton Roads). This stream formed the northern boundary of Vauxhall manor.

7 Eft to thare strate: Afterwards to the Street. This spot is by Kennington Park, where the boundary joins the Roman road.

8 Endlang street eft to Brixes stan: Afterwards along the street to Beorhtsige’s Stone. Like the boundary ditch on the western side of the estate, the Roman road is followed for more than two miles, back to the starting point of the perambulation.

With its combination of natural and man-made features, the 11th-century boundary clause for “Lambeth” is a typical example of its kind, differing mainly in having two-thirds of its course following only two features, the Boundary Ditch and the Street (Roman Road). This block of land became the medieval manors of Vauxhall and Stockwell.

Keith Bailey