Vauxhall Gardens: A History, by David Coke, Alan Borg

David Coke and Alan Borg, Vauxhall Gardens, A History. Yale University Press, London, 2011. ISBN 978-0-300-17382-6

Not long back, two curious columns sprang up at the southern entrance to Vauxhall Spring Gardens, the modern and, let’s be honest, pathetic equivalent to the celebrated Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens. As readers may know, these fat, black, shiny monoliths symbolize efforts by the Friends of Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens to cheer up a straggling and inconsequent open space (which David Coke and Alan Borg – C & B hereafter – mistakenly say is ‘surrounded by Tower Blocks’). More power to the Friends’ elbow. All the same, monumental concrete pillars in funerary black are a weird kind of homage to Jonathan Tyers’ immortal creation, which was all about good cheer and colourful frivolity. Happily, right next door stands a better memorial to the gardens, in the shape of the Royal Vauxhall Tavern. Chucking-out time at Vauxhall Gardens in the small hours two centuries ago probably resembled the weekend raffishness of the RVT pretty closely. As far back as records stretch, this bit of Vauxhall has always been louche.

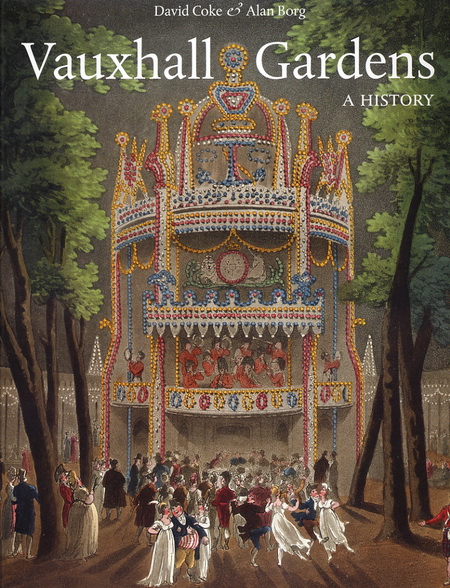

Vauxhall Gardens closed in 1859 after almost two centuries of giving pleasure. Another century and a half have gone by since, and still the legend endures. The Luton-based car factory and its output apart, it’s the only thing that Vauxhall means to strangers. Now at last Vauxhall Gardens has its true monument in this book, replete with exhaustive and illuminating detail. C & B chart the gardens’ rise and fall, from the years of fashionable success to those of bathos and failure. They illustrate every conceivable known view or work of art or relic associated with the place, from Roubiliac’s great statue of Handel to the entrance tokens and posters. Above all, they show that Vauxhall Gardens was more than a pleasure ground, it was a little world, and one dedicated to an optimistic outlook on humanity. Here in its palmy days visitors of every hue and view met on equal and amiable terms, prince and commoner mingling with one another and with artists, musicians and sundry performers.

Jonathan Tyers, the great name connected with Vauxhall Gardens, is central to C & B’s story. But Tyers was not the gardens’ founder. They can be traced back to 1661, when John Evelyn visited ‘the new Spring-Garden at Lambeth a pretty contriv’d plantation’. The term ‘spring gardens’ is a generic one for an early pleasure garden; the name refers to a water source, not the season (though C & B curiously question this). They began to be fashionable places of suburban resort during the Cromwellian years, less puritanical about recreation than we tend to think. After the Restoration they proliferated. The earliest were around the royal parks, but Clerkenwell and Islington soon acquired rivals including the famous Sadler’s Wells. The usual formula was a pub with a good garden offering walks, amusements or games and fresh running water.

Vauxhall started out as the pioneer of various waterside venues suitable for a summer evening’s boat trip from London. One stage further up river, Chelsea and Battersea Fields developed their own pleasure destinations a little later. Vauxhall Gardens themselves were never actually on the waterfront. To reach them after disembarking at ‘FFaux Hall Stairs’, you squeezed between scruffy semi-industrial premises, crossed a lane, and came into a square, tree-lined arbour with a few planted beds and one ramshackle building, if Thomas Hill’s 1681 map of Vauxhall is accurate. Not much, you might think. But it was enough to bring that hedonist Samuel Pepys several times, lured by the wenches and, more touchingly, the birdsong, for in those days there were nightingales in Vauxhall. There is no sign of a spring – the South Bank was too marshy for that – yet the name Spring Garden stuck.

There was nothing unique about the first Vauxhall Gardens. Yet they endured and were well patronized, not least as a pick-up joint, until 1729. At that point Jonathan Tyers leased the gardens from their owner, Elizabeth Masters. Tyers, as C & B depict him, was a complex character: shrewd, idealistic, upwardly mobile, not always plain-dealing, possibly manic-depressive. By trade a Bermondsey fellmonger, in other words a leatherworker, he migrated into the middle-class intelligentsia of Georgian London, and was close friends with Fielding and Hogarth. In many ways Tyers’s circle was the most radical and far-sighted group in eighteenth-century London. They believed that the urban middle class could create and direct a new kind of culture, on different terms from the old aristocratic style of patronage. Morality, art and education came together in their ideas. Higher standards of art, literature, entertainment and philanthropy were to raise levels of urban living and conduct.

These were the beliefs which Tyers brought to Vauxhall. To an extraordinary degree he succeeded. The grounds were extended, then regularly improved and updated. A charming series of paintings by Francis Hayman were introduced in the supper boxes lining the main walks. Roubilac’s marble Handel statue came in. Standards of musical performance rose. Frederick, Prince of Wales, figurehead for a less formal lifestyle, became the patron, was given his own pavilion, and mixed freely on his frequent visits. The fashionables flocked to Vauxhall Gardens, and on the whole people behaved themselves better. To keep the variety and interest up, Tyers organized an occasional ridotto al fresco, an entertainment on a grander scale than the normal nightly performances.

Much of C & B’s text covers the remarkable artworks commissioned by Tyers, the starting point for David Coke’s investigations. Readers may wish to skip some of this, but the record is valuable to have. Astonishingly, a few of the Hayman paintings survive in museums, the worse for wear, but sketches survive for many more. The whole series conveys the balance of education, amusement and patriotic fervour which Tyers purveyed. The Victoria & Albert Museum also has the Handel statue, one of the subtlest of Georgian works of art, and in tiptop condition considering the weather and indignities it must have been exposed to. The music inevitably comes over less well from the printed page. But a Handel concerto or a song or two from Thomas Arne on a CD will convey the atmosphere and confirm that here too Tyers procured the best talent London could offer.

Pleasure gardens by their nature are neither subtle nor sustainable. The structures at Vauxhall were gaudy rather than sophisticated, while the garden walks and the planting were always quite simple. Most impressive of all were the thousands of glass globe or ‘bucket’ lights hung from the trees, which allegedly could be lit almost simultaneously. These did not extend to the Lover’s Walk at the back of the garden, where goings-on were tolerated within bounds. Despite the lip service to civilization and morality, as Tyers well knew, prostitution, drunkenness and criminality persisted, just outside the gardens if not within. But for his lifetime and a little beyond they were kept within discreet bounds. Tyers’s enlightened vision lasted long enough for Vauxhall to become pre-eminent among pleasure gardens not only in London but beyond, and to lend its name to imitations abroad.

After his death in 1767 the gradual decline began. Tyers’s family kept the place on, no doubt because Vauxhall turned a good profit, but none of them had his genius in setting the tone. The main rival during Tyers’s lifetime was Ranelagh across the river in Chelsea, stodgier and staider. But from the 1770s promenading to music and eating the famous thin Vauxhall ham in the supper boxes seemed just not enough fun. Astleys in Westminster Bridge Road started to offer the vulgarity of showmanship and circus rides, and Vauxhall was forced to compete. Tastes had changed.

The next eighty years were an agony of ups and downs. Dancers, singers, acrobats and contortionists were brought in to keep up attendances, interspersed with melodramatic performances and loud fireworks. The grounds got remodelled again and again, to no lasting avail. Gradually ‘the quality’ melted away, to be replaced by a rougher crowd. Yet there was tremendous good will for Vauxhall, and the illusion of gentility was kept up. C & B paint a touching picture of ‘C. H. Simpson, esq., master of ceremonies’ in the later years, greeting punters with top hat and exaggeratedly dandified mien. Simpson survived to welcome the Duke of Wellington in 1833.

Following his death the downward spiral was unstoppable. By then Kennington and Vauxhall were built up, and the new residents resented the noise of the fireworks. The pretence that the gardens were a country resort had become a ridiculous illusion. Even so, Vauxhall survived and even briefly gained from the coming of the railway in the 1840s. After the gardens finally closed in 1859, everything was sold, lock, stock and barrel, and the site built over. Part of it became St Peter’s Church. On one side of the church is a former home for penitent prostitutes – an appropriate Victorian memorial to the gardens perhaps, but not one in the Tyers spirit. On the other side there still survives at 308 Kennington Lane a house of the 1790s built not for Tyers himself, as I had thought, but for his daughter in law Margaret. It is now the one physical survival on site from the days of Vauxhall Gardens.

This is an extraordinary book, blending meticulous scholarship with superb, elegant and funny illustrations. Jonathan Tyers would have beamed with pleasure to see his great creation thus virtually revived. C & B’s book is not cheap, but it should be on the shelves of every Vauxhall-lover. Without it you cannot understand Vauxhall itself and what it once meant for London.

Andrew Saint