by David E. Coke

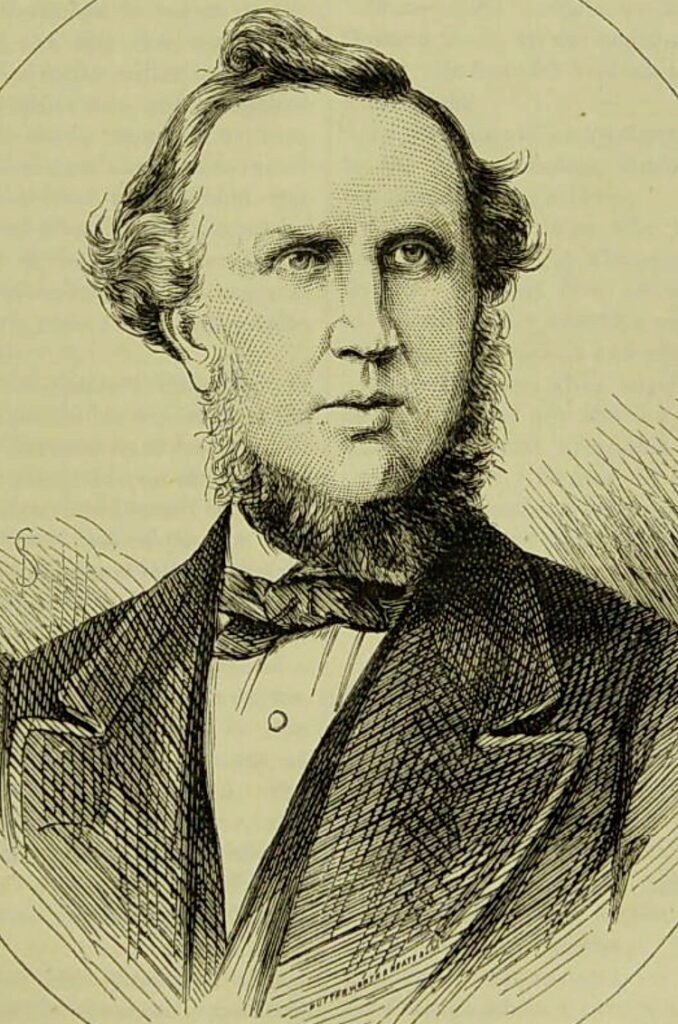

John Mackay (August 1818 – April 1881), pharmaceutical chemist, the son of Francis and Margaret Mackay of Edinburgh, stayed in London from 9 January 1837 until the end of March 1838, working at Bell’s pharmacy, 338 Oxford Street. On his return to Edinburgh, he started his own pharmaceutical company, which soon developed from a simple shop to a successful manufactory of artificial foods and soft drinks with branches in Edinburgh, Glasgow and Newcastle. From 1841 he devoted much of his time to the administration of the Scottish or ‘North British’ branch of the Pharmaceutical Society, later distinguishing himself as its Honorary Secretary.

‘. . . it is my painful task to inform you of an event which has been the means of plunging all in sorrow, namely, the death of our beloved monarch . . .’

This sentence was written not in September 2022, as might be expected, but almost two centuries earlier, in June 1837, on the death of King William IV, whose coronation had taken place less than six years before. The writer was a young Scotsman from Edinburgh called John Mackay, who had recently travelled to London to take up a post at the pharmacy of John Bell in Oxford Street.

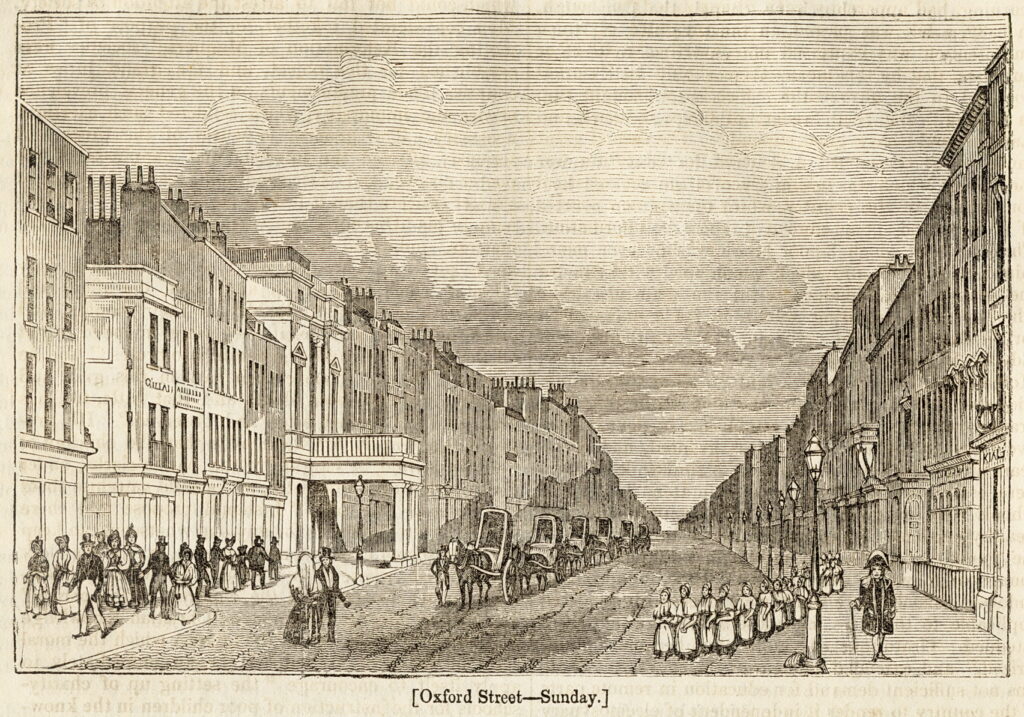

Having completed his apprenticeship in Edinburgh in the Autumn of 1836, Mackay felt driven to make the journey to London, where he hoped to acquire the polish and professional prestige that would aid him in his chosen career in pharmacy; in fact, he could not have picked a better place to work, as it was Jacob Bell, the son of John Bell, who would become a leading player in the 19th-century pharmaceutical profession, and in the formation of what became the Royal Pharmaceutical Society; it was Jacob Bell who entrusted Mackay with promoting the ‘North British’ branch of the society from his base in Edinburgh. In 1837, though, Mackay’s distinguished career was all in the future, and he was just one among the thousands of aspiring young immigrants arriving in London every year.

The General Steam Navigation Company’s steam-ship Clarence, with the 18-year-old Mackay among its passengers, docked at Blackwall on the morning of 10 January 1837 after the almost three-day sea-voyage from Leith Docks. The young Scot, leaving Scotland for the first time in his life, found himself immediately immersed in work as a shop-boy at Bell’s busy pharmacy counter, where their resources and staff were under pressure from an influenza outbreak raging through London. Much to his regret, he was to have no time to himself or to explore the metropolis at his arrival. Later in his London stay he did, of course, visit all the great sights of the city as well as many of the lesser ones, sometimes walking long distances to outlying places like Richmond, Muswell Hill, Epping Forest, or Clapham.

As a very ordinary young man-in-the-street, Mackay’s experiences would have been unremarkable, and would have been unknown to us had it not been for the survival of a manuscript journal kept by Mackay throughout his 15-month stay in London between January 1837 and March 1838. His thoughts and impressions of what he saw are all carefully chronicled in his journal. On his many walks, what he himself calls his ‘enquiring gaze’ took in all the sights and the streets, London at work and at play, and the crowds of his fellow-citizens, whether the disorderly and unwashed customers of a Bloomsbury gin palace or the demure young Queen Victoria on an outing in her carriage. His is a very personal view, creating a trenchant and compelling narrative that tells us so much more about London in 1837 than any orthodox history can. Mackay throws a very subjective spotlight onto the capital as it was at this fascinating time of transition between the Georgian and Victorian periods.

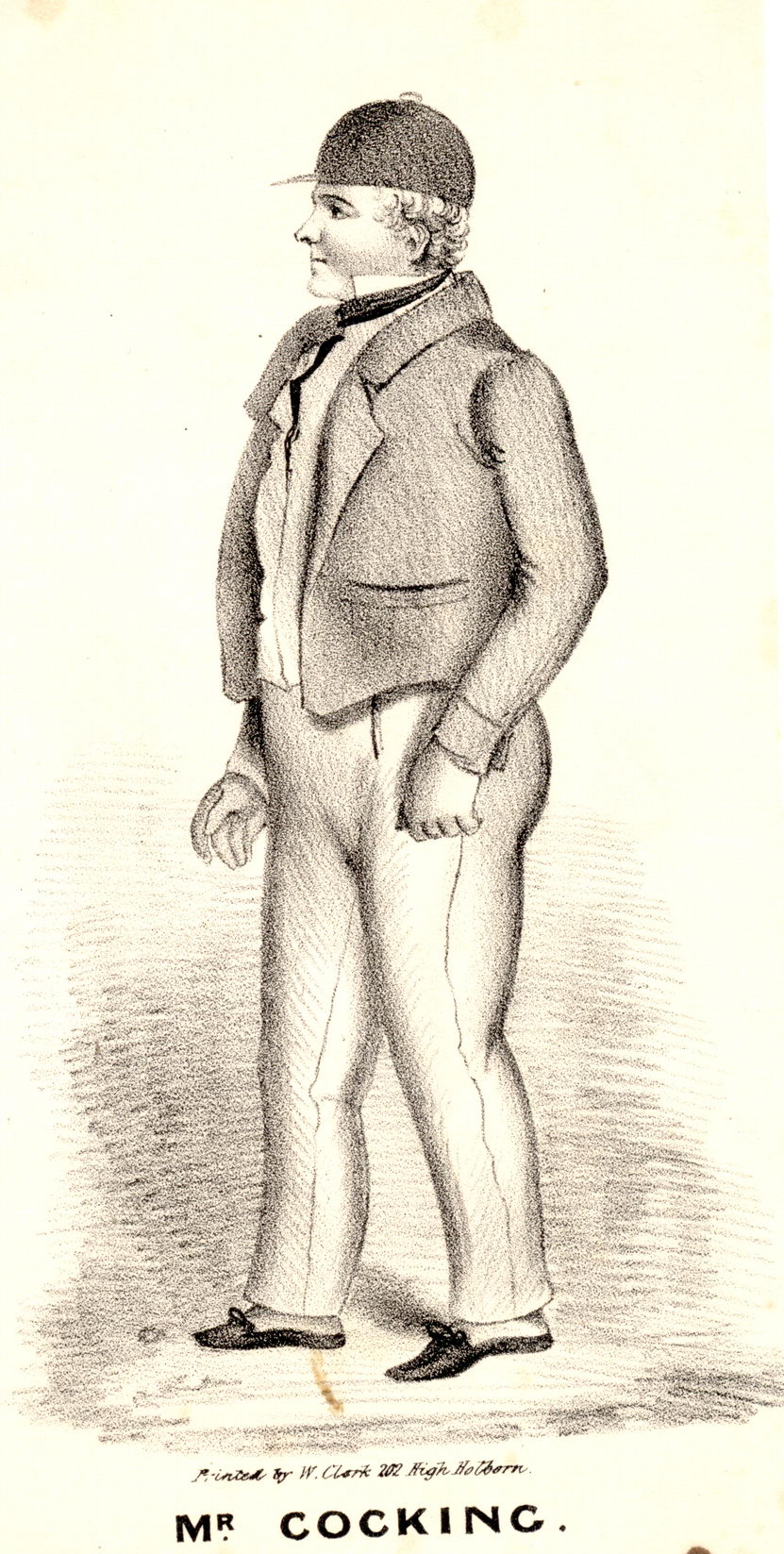

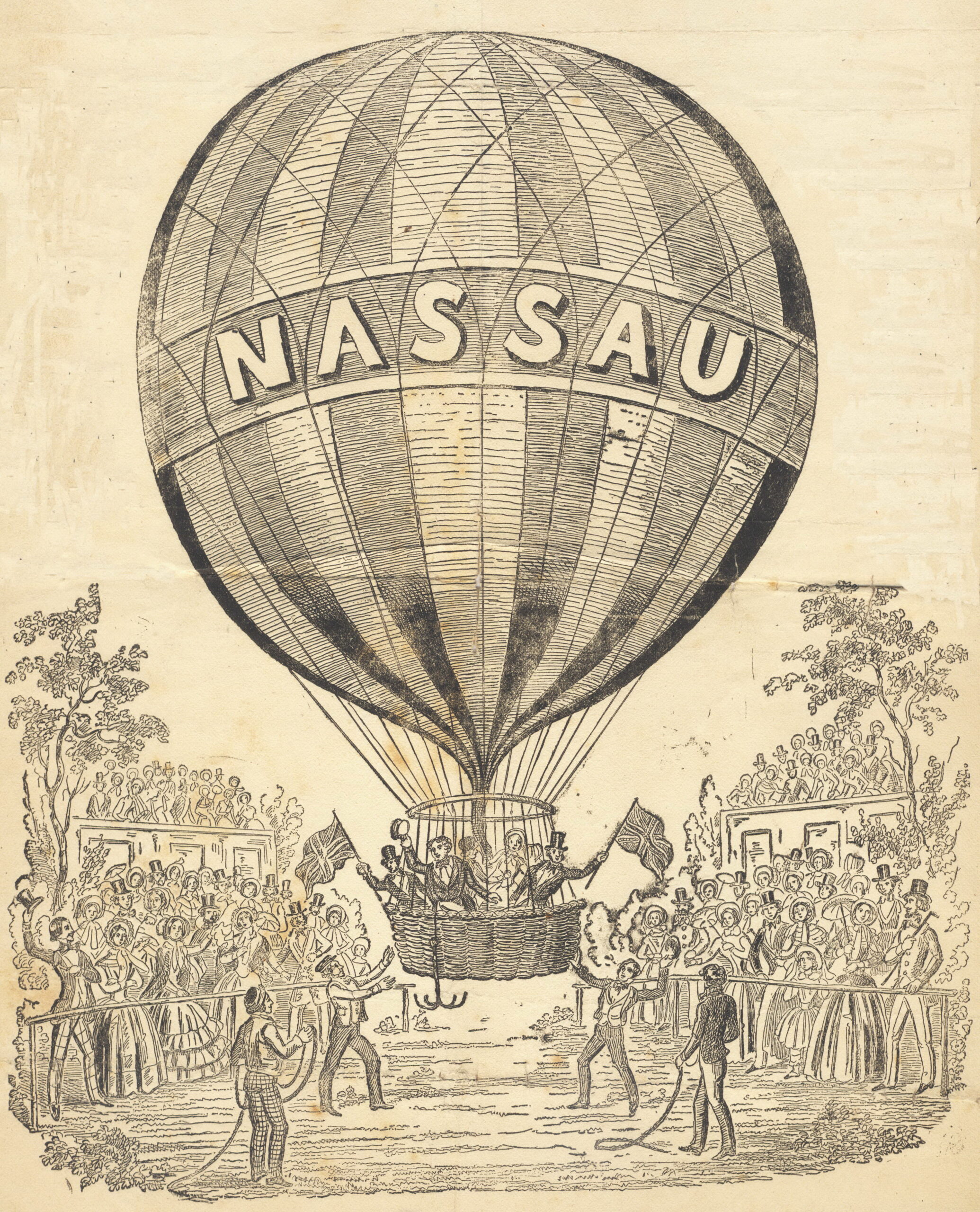

Preserved by Mackay’s descendants, the journal eventually ended up being offered for sale on an online auction site. At this stage it may well have sunk back into obscurity (or worse) had it not been for a lithographic print tipped into the Journal by Mackay himself. The subject of the print was the fatal experimental parachute descent of Robert Cocking from the Nassau Balloon, which had taken off from Vauxhall Gardens on 24 July 1837.

The inclusion of this lithograph led to the print (and therefore the journal too) being acquired for a private collection of Vauxhall memorabilia, and then to the transcription of the journal and its publication in July 2022 by the London Topographical Society, who saw its value to students of London’s history.

Why or where Mackay acquired the Cocking print for his journal is not explained – the journal includes nothing else quite like it – but he does record his own visit to Vauxhall Gardens several days after Cocking’s dramatic death, so it is possible that he bought the hastily-published print at Vauxhall itself. Writing on his 19th birthday which fell on Monday 7 August 1837, Mackay records that he had been given an admission ticket to Vauxhall. This must have presented him with something of a quandary – having been brought up in a strict Presbyterian household, Mackay was, by inclination, a sober and earnest youth, so an evening of unalloyed pleasure and entertainment would have been foreign to his usual experience. However, his admission ticket had come from his family, probably as a birthday gift, so he must have felt that he would not be actually culpable if he took advantage of it. He had made up his mind to use his ticket the preceding Monday evening 31 July, and, as it most likely admitted two people, he took his friend and fellow-apprentice Ralph Ferguson with him. At this time, because of decreasing profits, Vauxhall’s daily admission price was at its highest-ever level, and an ordinary single admission would have cost four £50.

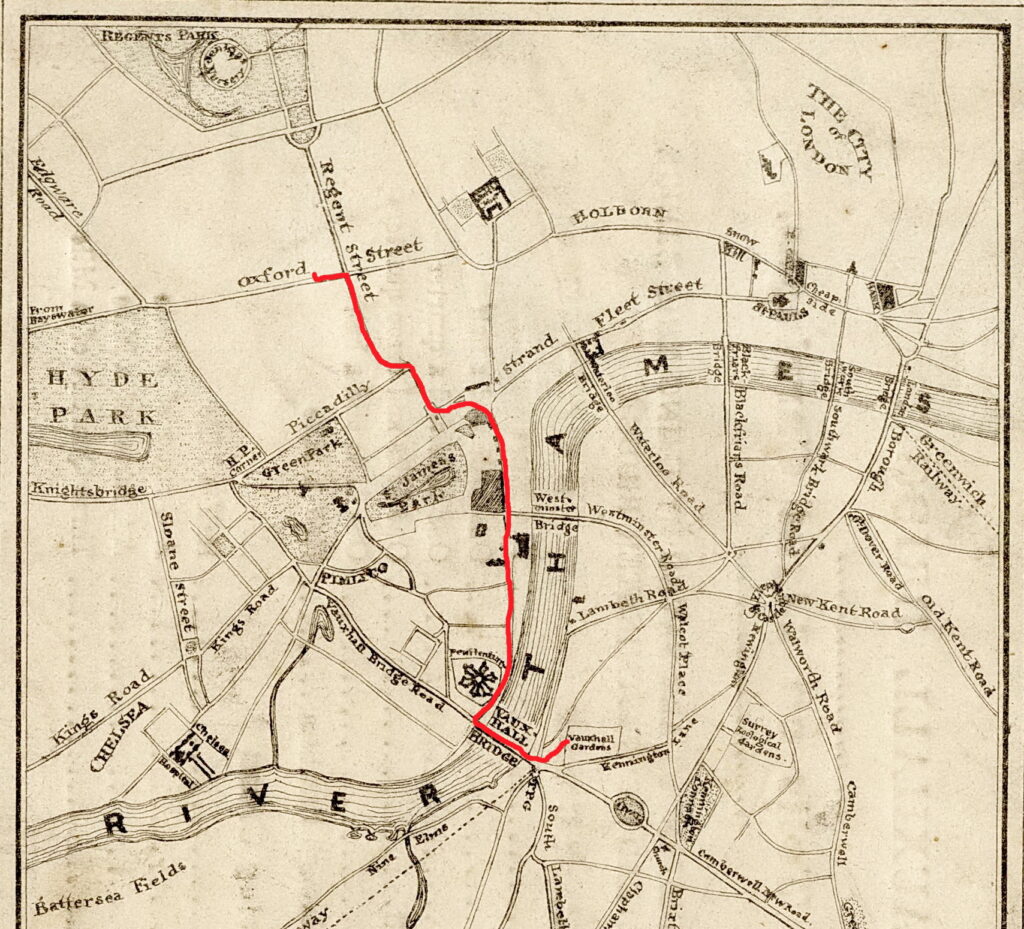

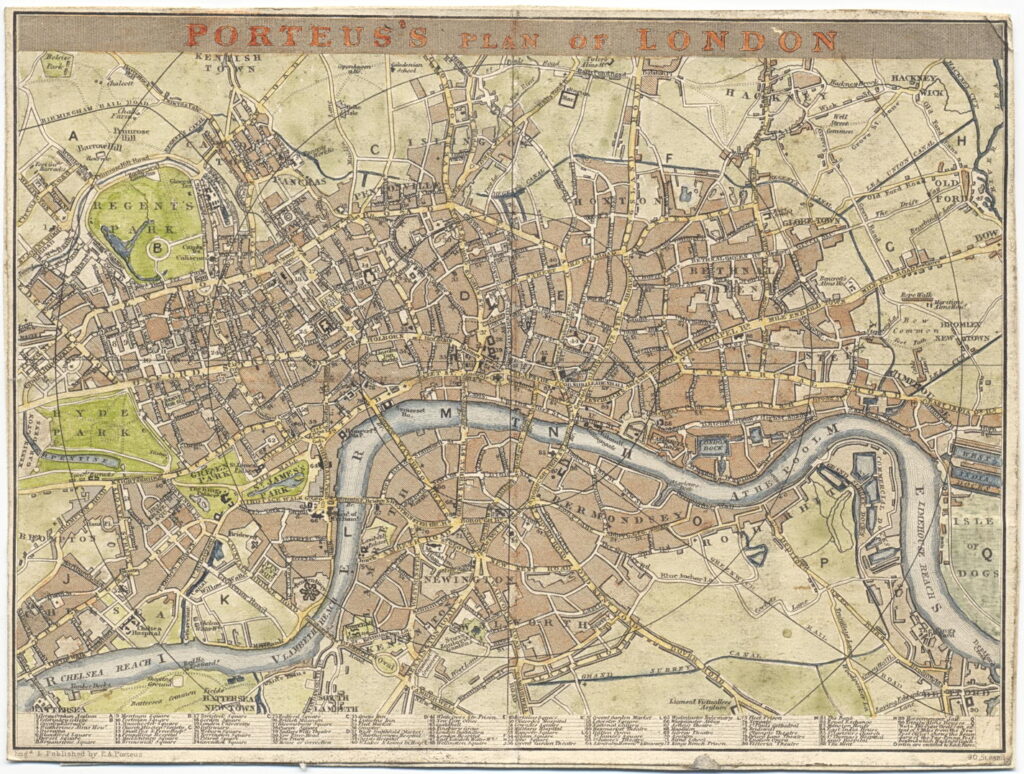

Mackay does not describe his journey from Oxford Street to Vauxhall on that Monday evening, but it is likely that, having finished his day’s work, he travelled on foot, as he almost always did, even for quite long distances.

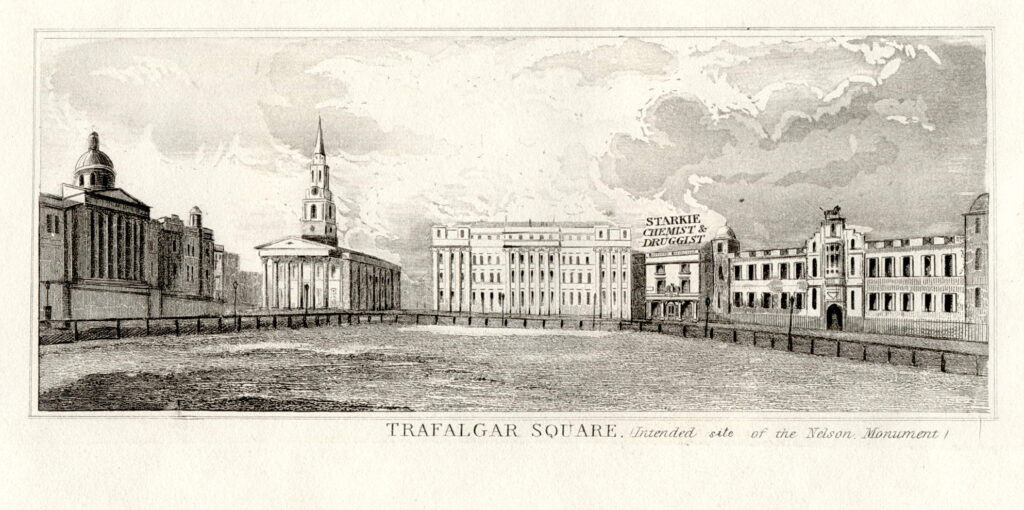

His experience of miserable seasickness on his voyage from Edinburgh to London would no doubt have put him off the idea of a river-crossing either by rowing boat or by Thames steamer, which was still a popular way to travel to Vauxhall; in any case, the walk would have been almost cost-free. His easiest land route would have taken him past the new shops of Regent Street, completed only 12 years earlier, and down the Haymarket with its theatre on the left and several pubs on the right, through the building site at Charing Cross that was being transformed into Trafalgar Square, where the National Gallery’s new building was nearing completion on the site of the old Crown Stables.

Then, walking down ‘Whitehall, past the Admiralty, the Treasury, and Horse Guards and on between Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament, still in partial ruins after the catastrophic fire of 1834, he would have arrived at the riverside, where the grim bulk of the Millbank Penitentiary loomed over the north end of Vauxhall Bridge, opened only two decades earlier. Paying his one penny toll to cross the bridge on foot, it was then just a short walk to the Gardens’ entrance, where things would have changed only little since the heyday of the Gardens in the 1750s. The main entrance or ‘Watergate’ to the Gardens was still through the grand Proprietor’s House, and the nearby Royal Vauxhall Tap, a pub belonging to the Gardens, still provided refreshment to those awaiting the official opening time. In 1837, Vauxhall’s doors opened later than usual, at 9 o’clock in the evening, so the Tap would have been well patronised. In front of the Proprietor’s House was the large open space of the carriage-park, with its sunken water-troughs at which horses could drink. All this would be irrevocably changed before the end of the next decade with the arrival of the railway, and the great viaduct carrying London and South Western Railway trains into Waterloo Station.

What had already changed significantly, however, especially since the completion of the first Vauxhall Bridge in 1816, was the extent of housing development in the Vauxhall area of South Lambeth. By 1837, it was well built up with housing and industrial buildings, mostly potteries, breweries, distilleries and glass-houses. The riverbank to the north of Vauxhall Bridge was crammed with factories, tenements and warehouses, and Kennington Lane was very much an urban street of housing and small shops. Many public houses, led by the venerable Royal Oak at Vauxhall Cross, competed with Vauxhall Gardens and its smaller neighbouring siblings, the Brunswick and Victoria Gardens, for the custom of local people. But to the south and west of the newly-built Harleyford Road, the land behind the houses was still open, with fields and gardens, although the next two decades would inevitably see those fields disappear under tarmac and masonry. The 11 acres of Vauxhall Gardens were already being sized up by house-builders, but they would have to wait another 20 years for their chance to develop the site.

Of his visit to Vauxhall Gardens on 31 July 1837, Mackay writes on his page 92 only briefly about the entertainments that he found there, probably not knowing how best to describe or judge them. He makes no mention of the fact that 31 July was a special day for the Gardens – the proprietors had organised a so-called ‘Gala’ to celebrate the fact that the young Queen Victoria had given her permission for the Gardens to continue to use the word ‘Royal’ in its official title. Had he visited on the day of his birthday, he would have stumbled upon a ‘Grand Masked Fete and Ball’, which would no doubt have sparked some invective in his journal against the immorality of such events.

The main attraction on that Monday of the Gala, as ever, would have been the music and song performed in the outdoor orchestra-stand; at this time Vauxhall’s music was directed by George Frederick Stansbury (1801-1845), a minor but spendthrift composer, musician, singer and conductor who never quite lived up to those honourable forenames, borrowed from the great G.F. Handel, Vauxhall’s first musical director a century earlier. The military band of the Surrey yeomanry provided stirring martial music under the baton of Mr Wallace, and pastoral, patriotic and comic songs were performed by the two Taylor sisters, Messrs Bedford and Buckingham, and by Stansbury himself as well. Miss M. Taylor no doubt sang her popular ballad My Bridal Day. An unexpected feature of the music that year was Mr Sedgwick’s performances on the patent concertina, a novelty recently imported from Italy.

But Vauxhall’s outstanding new attraction in 1837 was the so-called ‘Atelier de Canova’ – a living tableau of a sculptor’s studio filled with classical statues created using men and women in classical costume, or in skintight leotards to represent nude sculptures of marble. The following year, this display is described by an American visitor, the 28-year-old circus performer Joe Blackburn, who called it ‘a new style of statues after Canova by two men, three women and one child. This was the most beautiful exhibition it has been my lot to witness, especially the statues of ‘Three Graces’ by the women. With such exquisite forms, dressed in white tights, giving them the appearance of marble, a person could hardly imagine they were real flesh and blood.’ [1]C.H. Day & W.L. Slout, An Annotated Narrative of Joseph Blackburn’s A Clown’s Log, San Bernardino, Calif.: Emeritus Enterprises, 2005, 72. The supposed indecency of these ‘poses plastiques’ elicited much controversy, and it is safe to assume that Mackay would have studiously avoided them.

Less contentious would have been Vauxhall’s ‘picture-model’ of the first Thames Tunnel; this was a full-sized reconstruction, in timber and painted canvas of the entrance to the tunnel then being constructed between Rotherhithe and Wapping under the direction of Marc Isambard Brunel. Elsewhere in the garden, visitors could marvel at the 400-foot long ‘Grand Moving Panorama’ of the record-breaking voyage of the Royal Vauxhall Balloon from the Gardens to Weilburg in Germany the previous November; this is never described in detail, but must have been a large piece of scenery run between two rollers to show the landscape over which the balloon had passed on its 500-mile 18-hour flight.

However, it was the famed illuminations, more than anything else, that Mackay felt deserved a place in his journal. After sunset, at a signal from the Proprietor’s House, the whole Garden would be flooded with artificial light, one of the great ‘special effects’ to be seen anywhere in Europe before the introduction of electricity; Mackay was clearly captivated by this:

‘The illuminations are beyond imagination, in correctness of design, in brilliancy of appearance, and in magnitude they exceed all bounds of anticipation. – No less than sixty thousand lamps were employed that evening in the various decorations.’

One of the added attractions of the ‘Gala’ evenings was normally a series of emblematic tableaux made up of hundreds of lamps in different colours to represent the Royal coat-of-arms or other similar devices. The evening’s entertainments closed at midnight with a spectacular display of fireworks, under the direction of Herr D’Ernst, a favourite at Vauxhall since 1823.

Vauxhall’s outdoor illuminations represented a huge technological and scientific achievement, and the Thames Tunnel and the advances in balloon flights would also have been technological wonders, so it is a little odd that Mackay makes no comment about that aspect of what he was seeing, all for the first time in his young life. He may have felt that Vauxhall Gardens, as an entertainment venue, was not an appropriate place to be showing these modern marvels, and that he should not be seen to be gaining any pleasure or edification from his visit.

Mackay’s grudging admiration of Vauxhall Gardens, with its impressive lighting and decorations, is quickly tempered –

‘Certainly, so far as curiosity, and desire of seeing what is the talk of thousands who have been present, it is all very well, and accordingly to go there once, is sufficient, you see nothing to render you desirous to visit there a second time, and certainly there is but little to be learned.’

With this judgement, Mackay does leave us a remarkably rare example of a real criticism of Vauxhall Gardens; it is so unusual to find anybody writing anything negative about the gardens, that to read this entry comes as something of a shock. To assert that one visit is plenty for anybody, and, on top of that, to say that there is nothing to be gained culturally from a visit, even bearing in mind that Mackay was writing for the benefit of his family when he returned home, questions the whole ethos of Vauxhall, behind whose marketing there was always the assumption of repeated visits, and of the cultural benefits to be gained there.

However, in a rare moment of self-denigration, Mackay goes on to say that he was actually being a little disingenuous, and that he was in truth ‘much delighted’ to have had the chance to see it; in fact he took two of his friends there on a return journey on Friday 15 September to witness the ascent of Charles Green’s great Nassau Balloon; Mackay describes the preparations for the ascent in some detail, giving his second visit the spurious justification of scientific interest. It is well known that these balloon ascents were largely responsible for the longevity of Vauxhall, and that without them the Gardens would have failed long before it did. In the following year, 1838, it is recorded that on 14 Balloon days, the income amounted to £6,446, whereas on the 59 other days the income totalled only £5,544. [2]H.H. Montgomery, The History of Kennington and its Neighbourhood, London: H. Stacey Gold, 1889, p.108.

So, in spite of Mackay’s disapproval of Vauxhall, his journal entry still tells us a lot about Vauxhall Gardens at the dawn of the Victorian era. Balloon flights clearly exerted a real fascination on visitors, and brought them to the gardens in large numbers. In his own words he reports that Vauxhall was ‘the talk of thousands who have been present’; in other words, even by 1837, when Vauxhall was already more than a century old, it was still a great topic of conversation among the young Londoners that Mackay encountered. He also confirms that it was considered almost obligatory to have visited Vauxhall at least once in your life, if only so as to be able to contribute to conversations about it from personal experience, and that a ticket to Vauxhall was still considered to be a suitable gift. All of these were integral parts of the original marketing of Vauxhall Gardens under the first great proprietor, Jonathan Tyers, so it is remarkable to see that they endured long after his death and indeed into the Victorian period. It was during Mackay’s stay in London that Queen Victoria, a year younger than him, came to the throne at the death of her uncle King William IV – the occasion of the sombre quotation from Mackay’s journal at the opening of this essay.

David Coke is the author of The London Journal of John Mackay, 1837-38. London Topographical Society Publication no.185, 2022, which includes an introduction and a biography of Mackay as well as the edited transcript of his journal, all fully illustrated, with an appendix of information about his friends and contacts in London.