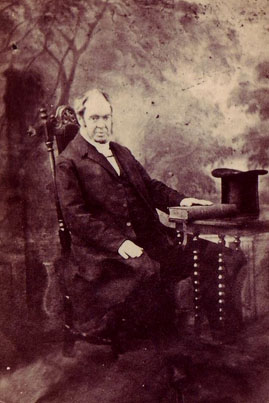

John Selby Watson

It had all the elements of a classic Victorian murder – so many it is almost a parody: the blood on the carpet in the study, the shrewish alcoholic wife, the devoted family servant, the prussic acid, the airtight chest ordered the day after the deed, the upright, uptight ‘gentle’ scholar also known for unpredictable outbursts…

And it all took place in 28 St Martin’s Road, Stockwell.

On Sunday 8 October 1871, Rev John Selby Watson, headmaster of Stockwell Grammar School (it was on the north side of Stockwell Park Road and built to accommodate 100 pupils) for 25 years and now in his sixties, murdered his wife Anne by beating her over the head with the butt of a pistol – so much so that her brain was said to look like jelly – stuffed her body in a room off his study, covered it with a blanket and tried to act normal.

When his maid Eleanor asked where the mistress was, he said she had gone out of town for a few days, and when she enquired about the dark stain on the carpet in the study he said it was port.

On Monday he ordered a big casket from the local case-maker.

But on Wednesday the strain had got to him and he tried to do away with himself by swallowing prussic acid (hydrogen cyanide), leaving a confessional note. The attempt was unsuccessful and his friend and doctor called in the Brixton police.

It appeared that Watson was about to be ‘let go’ from the grammar school and that Anne was not entertaining the idea of downsizing from their very nice house to fit their newly restricted income. Not only that, she was a bit of drinker and not very nice with it.

Watson was found guilty of murder at the Central Criminal Court in January 1872, but his death sentence was commuted to penal servitude for life. He died in Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight in 1884.

The case is mentioned in an interesting diary My Life’s Medley: Autobiography by F. Vincent Brooks.

The details differ in some respects, possibly because the diarist was a boy at the time of the events. Here is an extract:

” The cause of my leaving Stockwell Grammar School was that in the summer term of 1862 when I was approaching fourteen years of age I was the victim of an entirely undeserved and unmerciful flogging from the headmaster, who was a man of absolutely uncontrollable temper and quite unsuited for a schoolmaster.

A window was broken in the playground during play time : we all took to our heels and ran to the other side of the building, but the drill master and caretaker, a certain Sergeant Tully, caught me and ran me in to the “Head”. In vain did I plead that I had not thrown the stone but had only run away with the rest, my master was boiling over with rage and either could or would hear nothing.

Dr. Watson at once proceeded to birch me in the most brutal manner, while the sergeant held down my head : so excited did the master become that in his passion he tore his gown with the hand that was free. When he was exhausted he changed places with the sergeant and the agony of the fresh and stronger man “laying on” was unbearable and blood flowed freely.

This took place more than a mile from my home and when dismissed I started my journey there on foot as I had no money and felt unequal to facing my school-fellows to borrow any. Fortunately when about half way home I was overtaken by my form master, Mr Mansell, whom I remember as at all times a most gentle and kindly man : he was very sympathetic, put me in a cab and handed me over to the care of my mother more dead than alive.

My father, although a man of great kindness, was of a Spartan disposition in regard to bearing pain and I imagine never fully realised the agony I had been through. He, however, wrote a strong letter and removed me from the school.

It would indeed have been better if he had taken Police Court proceedings, though he would in those days have had difficulty in getting a summons granted, for shortly afterwards Dr. Watson’s temper again got the better of him ; this time it was at his home and he killed his wife with a carving knife in a paroxysm of rage while they were seated at the table.

The evidence at the trial showed that he had buried the body under the floor but eventually got a carman to take the box elsewhere. For some time the disappearance of Mrs Watson was a great mystery, but a large reward being offered the carman came forward and cleared it up.

Watson was convicted and sentenced to death, but great efforts were made for a reprieve; these were successful at the last moment, and after great pressure upon the Home Secretary Sir George Grey.

Had the execution taken place it would have been one of the two last at Horsemonger’s Lane Gaol. I remember that a man named Samuel Wright was executed on the day appointed, Jan. 12th 1864, and after the law had taken its course in his case there were persistent shouts for Watson.

Considerable protests were made in the press for it was felt that he had been spared on account of his cloth. The Doctor was sent away into penal servitude for life, but his detention was not to be prolonged for he committed suicide by jumping from a circular staircase – a truly appalling end to a life rich in opportunities. “

You can read more about this case at The Year Round: A Victorian Miscellany, SW magazine and Male Murders.

The story has inspired much literature:

- A Book of Remarkable Criminals, H.B. Irving

- Various Articles in the Penny Illustrated Paper, 1871 and 1872

- Watson’s Apology, Beryl Bainbridge (a fictional novel), 1985

- When Justice Faltered: A Study of Nine Peculiar Murder Trials, Richard Stanton Lambert, 1935