Juba, also known as Master Juba, was born William Henry Lane in 1825 in Mississippi, a free black man. As a teenager Juba grew up in the Five Points district of New York City and was influenced by the well-known black saloon dancer “Uncle” Jim Lowe. Lowe, best known for his jigs and reels, initially encouraged Juba to become a buck and wing dancer (buck = African-American males, wing = a pre-tap 19th-century dance routine done by minstrels).

Juba, also known as Master Juba, was born William Henry Lane in 1825 in Mississippi, a free black man. As a teenager Juba grew up in the Five Points district of New York City and was influenced by the well-known black saloon dancer “Uncle” Jim Lowe. Lowe, best known for his jigs and reels, initially encouraged Juba to become a buck and wing dancer (buck = African-American males, wing = a pre-tap 19th-century dance routine done by minstrels).

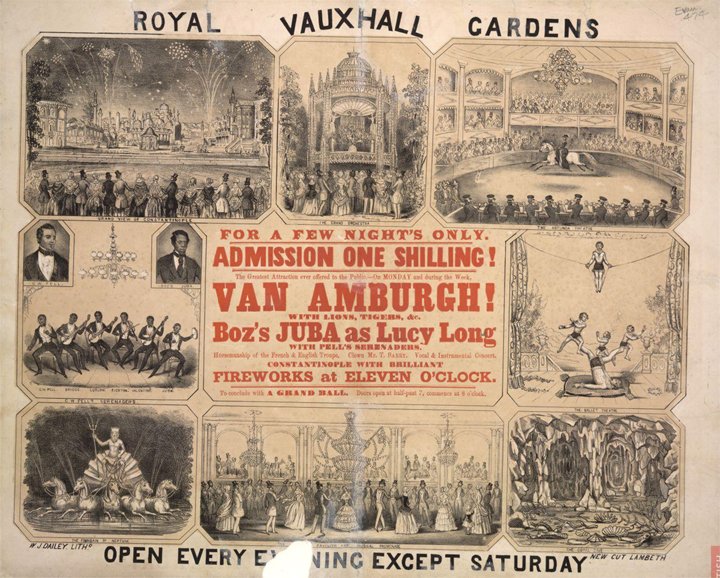

Juba , c1848

Juba went on to become the first great rhythm dancer, he entered and won many dance contests, twice beating the best white (Irish) dancer Jack Diamond. Juba himself encouraged another African-American named Johnny Diamond who went on to a triumphant career.

By 1845 Juba and his “Juba dance” was a mix of the (African) shuffle and slide and (European) jig, reel and clog steps. He emphasised rhythm and percussion over melody and was well versed in improvisation. He was perhaps the first to add syncopation to his dancing. It is hardly surprising that Juba was widely regarded as the best dancer of all time and is credited with inventing modern tap dancing.

In 1846, at a time when a colour bar was the norm, Juba got the top billing in an otherwise all-white minstrel company. He toured the US with his show and came to the UK and was again very popular. In 1848 he danced at Vauxhall Gardens and before Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace.

Details of Juba’s death are somewhat confused but he is thought to have died young, probably at the age of 27 somewhere in England.

Charles Dickens visited the Five Points district of New York and is thought to have written of Juba in his American Notes for General Circulation.

American Notes for General Circulation

by Charles Dickens

Our leader has his hand upon the latch of ‘Almack’s,’ and calls to us from the bottom of the steps; for the assembly-room of the Five Point fashionables is approached by a descent. Shall we go in? It is but a moment.

Heyday! the landlady of Almack’s thrives! A buxom fat mulatto woman, with sparkling eyes, whose head is daintily ornamented with a handkerchief of many colours. Nor is the landlord much behind her in his finery, being attired in a smart blue jacket, like a ship’s steward, with a thick gold ring upon his little finger, and round his neck a gleaming golden watch-guard. How glad he is to see us! What will we please to call for? A dance? It shall be done directly, sir: ‘a regular break-down.’

The corpulent black fiddler, and his friend who plays the tambourine, stamp upon the boarding of the small raised orchestra in which they sit, and play a lively measure. Five or six couple come upon the floor, marshalled by a lively young negro, who is the wit of the assembly, and the greatest dancer known. He never leaves off making queer faces, and is the delight of all the rest, who grin from ear to ear incessantly. Among the dancers are two young mulatto girls, with large, black, drooping eyes, and headgear after the fashion of the hostess, who are as shy, or feign to be, as though they never danced before, and so look down before the visitors, that their partners can see nothing but the long fringed lashes.

But the dance commences. Every gentleman sets as long as he likes to the opposite lady, and the opposite lady to him, and all are so long about it that the sport begins to languish, when suddenly the lively hero dashes in to the rescue. Instantly the fiddler grins, and goes at it tooth and nail; there is new energy in the tambourine; new laughter in the dancers; new smiles in the landlady; new confidence in the landlord; new brightness in the very candles.

Single shuffle, double shuffle, cut and cross-cut; snapping his fingers, rolling his eyes, turning in his knees, presenting the backs of his legs in front, spinning about on his toes and heels like nothing but the man’s fingers on the tambourine; dancing with two left legs, two right legs, two wooden legs, two wire legs, two spring legs – all sorts of legs and no legs – what is this to him? And in what walk of life, or dance of life, does man ever get such stimulating applause as thunders about him, when, having danced his partner off her feet, and himself too, he finishes by leaping gloriously on the bar-counter, and calling for something to drink, with the chuckle of a million of counterfeit Jim Crows, in one inimitable sound!

The air, even in these distempered parts, is fresh after the stifling atmosphere of the houses; and now, as we emerge into a broader street, it blows upon us with a purer breath, and the stars look bright again. Here are The Tombs once more. The city watchhouse is a part of the building. It follows naturally on the sights we have just left. Let us see that, and then to bed.