The following is an extract from the six-volume History of Old and New London by Walter Thornbury published between 1872-1878.

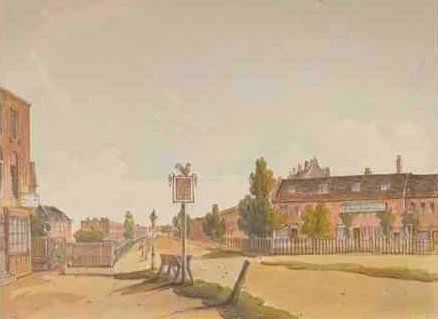

Kennington, c 1825

On the north side of Stockwell, and hemmed in by Walworth, Newington, and South Lambeth, is the once royal manor of Kennington. The name of Kennington, it is said by some topographers, was probably derived originally from the Saxon Kyning-tun, “the town or place of the king.” “In the parish of Lambeth,” writes Hughson, in his “History of London,” “is the manor of Kennington, which, in the Conqueror’s Survey, is called Chenintun. At that time it was in the possession of Theodoric, a goldsmith, who held it of Edward the Confessor. There is no record to show how it reverted to the Crown; but during the time of Edward III it was made part of the Duchy of Cornwall, to which it still continues annexed. Here was a royal palace, which was the residence of the Black Prince: it stood near the spot now called Kennington Cross. This palace was occasionally a residence of royalty down to the reign of Henry VII. After his time the manor appears to have been let out to various persons. Charles I, however, when Prince of Wales, inhabited a house built on part of the site of the old palace, the stables of which, built of flint and stone, remained in situ until the year 1795, when they were known as ‘The Long Barn.'”

Kennington is described in the “Tour round London,” in 1774, as “a village near Lambeth, in Surrey and one of the precincts of that parish.” It was formerly a lordship belonging to the ancient Earls of Warren, one of whom, in the reign of Edward II, being childless, gave the manor to the king. It had been already alienated, however, before the sixteenth year of Edward III, and was part of the estate of Roger d’Amory, who was attainted in the same reign for joining with sundry other lords in a seditious movement. Coming once more into the hands of the king, it was made a royal seat, and became shortly afterwards the principal residence of the Black Prince. The author above quoted states of this once abode of royalty, that “there is nothing now remaining of this ancient seat but a building called The Long Barn, which in the year 1709 was one of the receptacles of the poor persecuted Palatines.” It is generally accepted as a certainty that there was a royal residence near the spot now known as Kennington Cross as far back as the Saxon times; and here, says tradition, Hardicanute died in the year 1041. This amiable King of Denmark, third son of Canute, succeeded to the English crown on the death of his brother, Harold Harefoot, whose body, it is related, he caused to be dug up from its tomb at Winchester, and afterwards to be beheaded and thrown into the Thames. “Some good fishermen,” so runs the story, “found the mangled trunk of the dead king, and decently interred it in the church of St. Clement Danes. The peculiarly clement Dane who ruled over them, however, directly he heard of their pious act, again ordered his brother’s body to be flung into the Thames.” Two years afterwards Hardicanute went to Kennington (or, according to another account, to Lambeth), in order to honour the nuptial feast of a Danish lord; and there, within sight of the river on the banks of which Harold’s corpse had been washed by the stream, he fell dead, amidst the shouting and drinking of the guests assembled at the marriage banquet.

In 1189, Richard of the Lion Heart granted the manor to Sir Robert Percy; and it was afterwards the subject of frequent royal grants. As stated above, it seems to have been rather a favourite residence of Edward the Black Prince; and the road by which he reached the palace from the landing-place at the water-side, nearly corresponding with Upper Kennington Lane, long retained the name of Princes Road. Here died that powerful vassal of Edward I, John, Earl of Warren and Surrey, in September, 1304.

Again, the kings of Scotland, France, and Cyprus being in England in the year 1363, on a visit to Edward III, Henry Picard, who had been lord mayor, had the honour of entertaining these four monarchs, with the Prince of Wales and other illustrious persons. At another time, the citizens gave a grand masquerade on horseback for the amusement of the Black Prince’s son, Richard (then in his tenth year), and his mother, Joan of Kent. The procession set out from Newgate, and proceeded to Kennington, and was composed of stately pageants, in masques, one of which represented the pope and twenty-four cardinals. This “great mummery” consisted of 130 citizens in fancy dresses, with trumpets, sackbuts, and minstrels; and they danced and “mummed” to their hearts’ content in the great hall of the palace; after which, having been right royally feasted, they returned again to the City by way of London Bridge.

Nineteen years afterwards, when the young king wanted money, and to that end made up his mind to take a second wife, he married Isabel, daughter of Charles VI of France – the “little queen,” as she was pettingly styled, for she was but a child, under eight years of age. The royal train, on approaching London, was met on Blackheath by the lord mayor and aldermen, habited in scarlet, who attended the king to Newington (Surrey), where he dismissed them, as he and his youthful bride were to “rest at Kenyngtoun.” When the poor child was taken from Kennington to her lodgings in the Tower, the press to see her was so great that several persons were crushed to death on London Bridge – among them the Prior of Tiptree, in Essex.

At Kennington, John of Gaunt sought refuge from the citizens, after he had quarrelled with the Bishop of London. The proud Lancaster was one of the protectors of Wyclif, who was, of course, particularly unpopular with the prelates, and had bearded the bishop in a very irreverent manner. The good churchmen of London, who had small respect for royalty when royalty chanced to offend them, chased the ducal offender in the very same year in which they danced before his nephew, and he was glad to be quiet for some time in the old palace. His son, the fiery Bolingbroke, after he became king, sometimes resided here, as did his grandson, the unfortunate Henry VI, and Henry VII, and Katharine of Aragon. James I settled the manor of Kennington on the Prince of Wales, and it has ever since formed part of the princely possessions. The manor had been purchased in November, 1604, by Alleyn, the player, and founder of Dulwich College, for £ 1,065, and sold five years afterwards by the astute actor – who knew how to turn a penny, and made good use of his savings – for £ 2,000. It was of him, probably, that it was purchased by James I, who rebuilt the manor-house. The last fragment of the old palace – the “Old Barn,” or “Long Barn” remained till near the close of the last century; and the old manor-house itself, having served for some years as a Female Philanthropic School, finally disappeared in 1875. From an account of the building, published at the time of its demolition, we gather the following interesting particulars:- The first object which struck the visitor was the canopied head to the outer doorway, supported by finely carved trusses. The entrance door was very massive, and the large lock and unwieldy bar were suggestive of the times when every precaution was necessary for the safe custody of property. The rooms were square and lofty, with old-fashioned chimney-openings. The finest specimen of decorative art was, without doubt, the modelled plaster ceiling in the back room. The enrichments were finely undercut and in alto-relief, the mouldings and border being in true character with the other portions. The staircase was of massive oak, and the mouldings cut in the solid. The doors and the wainscot dado were also solid oak, the latter being a particularly fine specimen of wainscoting. The substantial timbers, door, and window-frames and heads to the last were in an excellent state of preservation. The estate having been leased to a speculative builder, the old house was demolished in order to make room for modern residences. Here, on a waste piece of land belonging to the Prince of Wales, as part of the old royal palace and demesne, lay for some years a quantity of the marble statues which had been removed from Arundel House, in the Strand, and which afterwards decorated “Kuper’s Gardens,” the site of which we shall presently visit. Here they were discovered by connoisseurs, and were purchased, some by Lord Burlington for his villa at Chiswick, and others by Mr. Freeman, of Fawley Court, near Henley-on-Thames, and by Mr. Edmund Waller, of Beaconsfield. Others were cut up and used to make mantel-pieces for private houses in Lambeth.

Kennington Common and Church

It would appear that Kennington is still regarded as an appanage of royalty; at all events, it gave the title of earl to the hero of Culloden, William the “butcher,” Duke of Cumberland, the younger son of George II. The duke’s name is kept in remembrance here by Cumberland Row, close by the Vestry Hall, Kennington Green: it forms a low row of cottages, bearing date 1666. Their unfinished carcases had been used as a lazarhouse [leper house] during the great plague of the previous year. The Prince of Wales, it may be added, is still the ground landlord of several streets in Kennington.

The manor of Kennington subsequently reverted to the Crown, and was granted by Charles I, when Prince of Wales, to Sir Noel Caron and Sir Francis Cottington. Sir Noel Caron was Dutch Ambassador to the English Court during the early part of the seventeenth century. He erected here a handsome mansion, with two wings. On the front was the inscription, “Omne solum forti patria.” He built also on the roadside the almshouses near the third mile-stone for seven poor women. His name is inscribed on their front, with the date, 1618, and a Latin inscription to the effect that “He that hath pity on the poor lendeth to the Lord.” Caron House, and the gardens attached to it, are memorable as having been granted by Charles II to Lord Chancellor Clarendon, who sold them to Sir Jeremias Whichcote. The London Gazette tells us that the prisoners from the Fleet were removed hither after the Fire of London; it was pulled down soon after, and the last remains of the house were removed early in the present century. What remained of it in 1806, when Hughson wrote his “History of London and its Suburbs,” was used as an academy, and still retained its former name of Caron House. Not far from it was-and perhaps still is – a spring of clear water called Vauxhall Well, which is said not to freeze in the very coldest winters.

A portion of the site of Sir Noel Caron’s park is absorbed in the well-known cricket-ground called Kennington Oval, which shares with “Lord’s” the honour of being the scene of many of those doughty encounters between the heroes of the bat and ball which have made the “elevens” of the north and south, of Surrey and Nottingham, Kent and Sussex, United and All England, all but immortal. The Oval, which, within the memory of living persons, was a cabbage-garden, covers about nine acres of ground, and is set apart entirely for cricket-matches. It was first opened as a cricket-ground on the 16th of April, 1846, as the speculation of a man named Houghton. The Surrey Club have held it for many years on a lease from the Duchy of Cornwall, to which the land hereabouts still belongs; a fact which is kept in remembrance by the “Duchy Arms” inn, “Cornwall” Cottages, &c.

At various times, Kennington has been the residence of many eminent persons, among whom we may mention John, seventh Earl of Warrenne and Surrey, father-in-law of John Balliol, who died here in 1304; David Ricardo, the celebrated political economist; the Duke of Brunswick; William Hogarth; and Eliza Cook, who lived here for many years. It has also been the home of many persons connected with the theatres. Here died, in 1877, Mr. E. T. Smith, of Cremorne, the Alhambra, and Drury Lane celebrity.

Kennington in its day has seen its deeds of violence; for it appears that in 1323 Elizabeth, the wife of Sir Richard Talbot, of Goderich Castle, in Herefordshire, was forcibly seized at her house in this parish by Hugh Despencer, Earl of Gloucester, in conjunction with his father, Hugh, Earl of Winchester, and carried off. It is satisfactory to know that for this act the Despencers suffered the extreme penalty of the law; the head of the younger one being set up on London Bridge. Their estate, of course, became confiscated and pounced upon by royalty; and the king very naturally bestowed it on the Prince of Wales, to whom it still belongs.

Text source Perseus Tufts University

See also Extract about Kennington in the period before the Norman Conquest from History of Kennington by the Rev H. H. Montgomery, published in 1889. It is a charmingly written work, and now a valuable collector’s item.