The text below has been compiled from various websites, particularly Peter Higginbotham’s Workhouse site and England’s Poor Law Commissioners and the Trade in Pauper Lunacy website.

Related links

Inquest on boy flogged at Lambeth Workhouse

‘A Night in a London Workhouse’ (song)

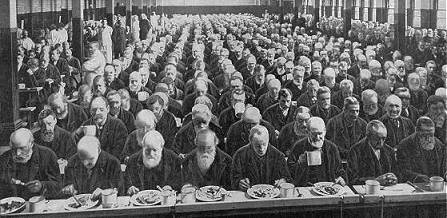

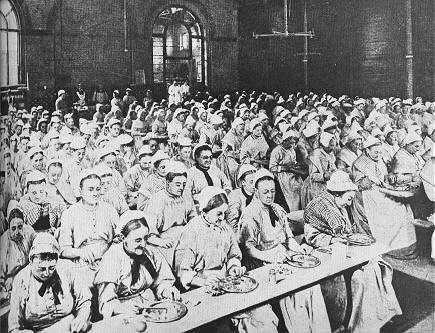

The workhouse system provided basic sustenance for the very poor, infirm and aged, often in return for some unpaid work. First established during the Elizabethan era, a Parish would elected overseers to provide relief for the sick, and work for the able-bodied poor, in the Parish workhouse. Parishes could provide either outdoor relief (usually in the form of food), or indoor relief in the (residential) workhouses. In 1662 the law was changed and enabled the overseers to expel any poor not born in the parish where they sought relief. Conditions varied but were generally harsh and punitive, for example on entering the workhouse an individual lost all voting rights and was subject to a regime of meagre food and irksome work such as stone-breaking. Parishes often took out contracts with local businesses to run their workhouses and asylums. The Lambeth Workhouse was north of Lower Kennington Lane and east of Renfrew Road.

Around 1820 Mr Mott, a Lambeth shopkeeper, decided that most paupers were pampered and later stated:

“Some rates were applied for which I thought exorbitant, which induced me to investigate the management of the parish; and in consequence of that investigation, the rates were greatly reduced.” Mott decided that he could manage the parish poor “better… and at a cheaper rate” than the parish officers. About 1831 Mott secured the contract for “maintenance of the poor of Lambeth, at 3/11d per head – men, women and a few children – able bodied, decrepid, impotent, all included.”

There were on average 700 indoor paupers in Lambeth and it was said by the Lambeth Vestry that the contract system had saved them £3,000 a year. Mott had found the Lambeth workhouse scales half an ounce out when he took over: half an ounce in favour of the paupers; due to an accumulation of dirt on the scale that took the weights. So he had the scales scrubbed and adjusted “with nicety”, annually by a scale maker and daily by the people who used them. Mott was adamantly opposed to what he called: “The tendency… to a constant increase of diet and accumulation of comforts from the interference and influence of humane but mistaken individuals.” The example he gave was of a county magistrate who had distributed some small parcels of tea to several of the old inmates at Lambeth and had recommended an allowance for the “comforts” of tea and sugar to the elderly paupers. Mott remonstrated with the parish officers, but to no avail. Ever since they had “allowed ninety-five old inmates 6d each week in addition to their allowance of food” and this had cost the parish over £125 a year. “Humane individuals rarely calculate upon the tendency or aggregate effect of such alterations,” Mott complained. The extension of this indulgence, however, was checked by the contract system. “But had the workhouse been under the old management, the probability is that the indulgence would have been extended to the greater proportion of the inmates.” He considered that paupers were not entitled to such indulgence.

At one stage Mott became a ‘Guardian of the Poor for the parish of Lambeth’ as well as being a contractor to the same Guardians. Under his influence the Lambeth Parish sent their ‘lunatics’ to Mott’s Peckham House Lunatic Asylum. This asylum also took in people from about 40 other parishes.

Residents of Mott’s etablishments would have a meagre diet, for example dinner, on alternate days, at Peckham was officially “meat, potatoes and bread” and “soup and bread” (“The soup is made from the liqueur in which the meat for the whole establishment is boiled the previous day, together with all the bones, with the addition of barley, pease, and green vegetables”). The seventh day was “Irish stew and bread”. The quantity of meat used was not stated. But there were numerous complaints of short measure, poor quality, fraud and false accounting. In October 1829 an official inspection found “the pea soup distributed to the paupers to be sour, of bad quality in other respects, nor do they conceive the bread which they saw given with it was in sufficient quantity”. In 1830 the kitchen was “extremely dirty ” wholly insufficient in size ” the persons employed in it “slovenly and the utensils bad.”

These findings did not stop Mott from becoming an Assistant Commissioner of the Poor Law Commission in 1834 and setting up yet more establishments. Mott’s houses were seriously overcrowded, with poor equipment and facilities, the staff were poorly trained and managed, the death rates were high and there were complaints of physical abuse.

During the later part of the 1830s and early 1840s the Poor Law Commission attempted to abolish all out-door relief, sending the able-bodied as well as the sick to the workhouse. This was very unpopular and many deserving cases preferred to suffer at home rather than go into the workhouse. Consequently the total numbers claiming help dropped and Mott is reported to have said “The Poor Law Amendment Act may indeed be called an act of renovation, for it causes the lame to walk, the blind to see and the dumb to speak.”

In the early 1840s another of Mott’s establishments (Haydock Lodge near Winwick in South Lancashire) was found to be:

1. grossly overcrowded

2. afflicted with dysentery and diarrhoea

3. lacking adequate supplies of water for baths

4. lacking sufficient blankets

5. serving poor food including liquid diets two days running

6. taking in too many seriously ill patients

7. physically ill-treating patients

8. have a very high death rate

9. slow in acting on the recommendations of visiting inspectors

10. maintaining inadequate accounts

Because of Mott’s position, it appeared to many that the Poor Law Commissioners were, among other things, running an asylum and permitting the ill-treatment of patients. This caused a major scandal and Mott was sacked in 1842.

From the 1870s the discipline was relaxed and orphans would be placed in smaller institutions or with foster parents. By the end of the 19th century workhouses had become more specialised, serving the functions of hospitals and asylums.

The remaining administration block of the Lambeth workhouse in Renfrew Road has been redeveloped and is currently home to The Cinema Museum. As a child Charlie Chaplin was an inmate in Lambeth Workhouse, when his mother faced destitution.

Peter Higginbotham’s Workhouses website has a section devoted to Lambeth workhouse.