The following article appeared in the Vauxhall Society Newsletter in the early 1980s

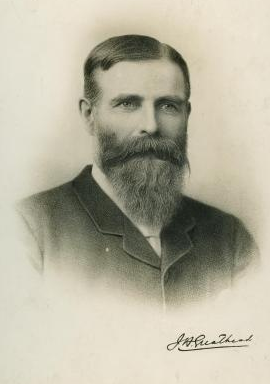

James Henry Greathead

Three of London’s oldest tube stations are at Kennington, Oval and Stockwell, and one of the very newest, at Vauxhall itself.

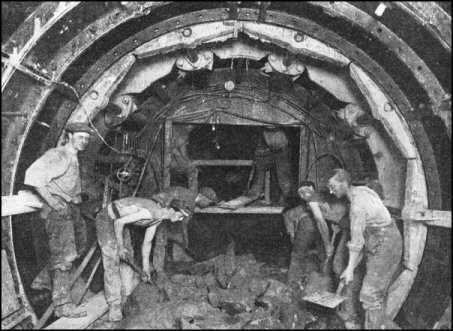

The oldest stations were completed originally by the City and South London Railway Co. and opened, after three years of work, by the Prince of Wales on 4 November 1890. The Company’s line ran from King William Street in the City to Stockwell and was the first deep-level underground electric railway in the world. Its method of construction, using a tunnelling shield patented by James Henry Greathead (1844-1897) became standard for virtually all the later tube railways of London up to the building of the Victoria Line in the 1960s.

In the first year over 5 million people used the line. Even so, the revenue from all these enthusiastic Kenningtonians and sightseers was insufficient to pay any dividend on the Company’s shares – a result which much of the capital investment in London’s tube railways was to duplicate ever afterwards. Nevertheless, the City & South London was seen by its promoters as a success, and soon led to a flood of other underground railway schemes, of which the Central London Railway from Shepherd’s Bush to the Bank and the Waterloo & City were the quickest off the mark. In the peak year of its success, 1902, the City & South London paid a 3.25% dividend on ordinary stock.

The Greathead Shield

If we were to journey with a typical turn-of-the-century traveller – a banker’s clerk, say, from Kennington to the City, we should probably wonder why the line was so popular. We enter the single-storey brick booking-hall of Kennington New Street (as it was then called) through a large doorway situated diagonally across the corner of the station building. This was a favourite feature of the architect T. P. Figgis, which he repeated at several other stations. The interior was not tiled until the Northern Line modernisation scheme of 1922-24 when the booking office was moved from one side to its present position below the edge of the dome. The dome we cannot see much of from the inside, because it contains the lift machinery – hydraulic originally, although Kennington became (in 1897) the first station ever to have a lift converted to electric operation. Over the years, other stations were also converted, until the hydraulic main, fed by the power station at Stockwell, was eventually abandoned.

We buy our 2d ticket (a flat fare) and descend the 60 feet shaft to the lower lift landing from where passages slope up and down to reach the murky wooden platforms. The northbound and southbound platforms are at different depths, and staggered each side of the shaft, so as to minimise the walking distance for passengers. Each station tunnel, brick-lined, is only 200 feet long and ten feet narrower than the one we know today; it is however electrically lit, in place of the yellow gaslight which originally served the line.

A typical wait of five minutes is rewarded by the rumbling approach of a three-car train, drawn by a tiny orange-painted locomotive at a gallant speed of just under 15mph. Entrance to the varnished wooden cars is via a ‘verandah’ at each end, guarded by a gateman. He closes the lattice gates before we move off down the sharp slope away from the station, which is designed to give us a good start. A notice in the car warns against the virtually impossible feat of riding on the car roof, at a penalty of £2.

The accommodation provided by these “padded cells” is decidedly cramped. A ceiling only seven feet high – and no windows apart from small quarter lights above the high-backed inward-facing padded benches. The lamps, fed from the traction supply (live rail), go dim as the train accelerates, and on the climb up to King Willam Street from under the bed of the Thames, they fade to a dark red.

On our way, we pass through Elephant & Castle station, with its standby locomotive in case we fail, and then Great Dover Street (now known as Borough). There was no station at London Bridge in those days, although one is under construction as part of a deviation and extension of the line to Moorgate Street (now Moorgate). The route we follow has been laid out originally for cable rather than electric haulage, and it abounds in tight curves and steep gradients, which no doubt contribute to the generally noisy ride. At the little island platform terminus of King William Street, we alight and take the lift to the surface, where, blinking in the unaccustomed brightness of the daylight we proceed on our way.

The halcyon years of the early 1900s were soon over for the proprietors of Kennington New Street. The City & South London Railway (CSLR), running from Stockwell to Moorgate and later Euston, was suffering increasing competition from tramways along Clapham Road and Kennington Park Road which had been taken over and electrified by the London County Council. In 1912, Underground Electric Railways Co of London, which had already acquired several other tube lines, made an offer to the CSLR shareholders. Without huge new investment, the little pioneer line could never fend off the competition, and the offer was thankfully accepted.

Since the Underground Co controlled other tramways and the London General Omnibuses through bookings between different modes of transport were greatly expanded (something impossible today). The T-O-T (Train-Omnibus-Tram) tickets introduced in 1914, enabled one to ride from Kennington to Clapham by tube and continue the journey southwards by tram or bus. An integrated transport system moved a step closer.

Within three years of the takeover, Kennington enjoyed the sort of boom in traffic that might have kept the CSLR independent. Much of this was due to the First World War, with the constant movement of troops and reductions in road services owing to staff shortages and requisitions of vehicles. As a precaution against air attack, street lighting was dimmed and travel by tube seemed safer and brighter by comparison. The beginning of Zeppelin raids in May 1915 produced a new and unexpected clientele for the underground stations – frightened crowds prepared to camp out on platfoms and stairs overnight.

So severe was the congestion at Kennington by 1918 that a platform queue system was introduced. Passengers queued opposite the point where the entrance gates on the tube cars were expected to stop; but there was little saving in time and many more station staff were needed. The experiment was abandoned within a year.

The case for modernisation had now become acute, and in 1922 works began which were to transform Kennington out of all recognition – below ground level. First, the train tunnels had to be enlarged and the platforms extended to take faster and more modern rolling stock. To speed the work, Kennington and Borough stations closed in May 1923 and a limited service ran from other stations. Substitute buses were also put on, and the LCC, hoping to increase the popularity of its trams, strengthened services along Clapham Road.

Then, in November 1923, after a train collided with engineering works near Elephant & Castle, the whole route from Euston to Clapham was closed. A year later, in December 1924, services were re-introduced on what we know now as the City branch of the Northern Line. Through trains could run from Clapham to Edgware, a journey of 52 minutes costing 10d (4p). Traffic increased by a third in 1925 as a result of these improvements. Kennington station however was in use as a working site for the new connection to Charing Cross (now Embankment) and did not reopen until July 1925.

Passing below the Bethlem Hospital (now the Imperial War Museum) and Lambeth Workhouse, this connection involved a complicated junction, with four platforms, at Kennington. Not surprisingly, illuminated train destination indicators were required

to help passengers find their way through the considerably more complicated network of lines. To complete the modernisation, new rolling stock with pairs of sliding doors and much improved lighting was delivered to work the services through Kennington. Some of this stock, now fifty years old, is still at work on the railways of the Isle of Wight, having been sold to British Rail in 1966.

The architecture and services through Kennington have remained relatively unchanged since the 1920s. The atmosphere of the station remains commonplace and these days rather more grimy. Trains terminated at Kennington from the south (always an unusual occurrence) for some months in 1939-40 while flood gates were installed as a precaution against bombs falling on the Thames and puncturing a tunnel. And after the war, Kennington might have become an interchange station with a new deep-level tube to Raynes Park and Cheam which was projected but never built. Today, few signs of the station’s origins with the CSLR are evident: below ground, some projecting edges in the station tunnels show where they were lengthened; on the surface, the fine dome remains in place, albeit disfigured by access doors to the lift machinery. Inside, one wonders how long we shall wait before there is a fresh modernisation on the scale of fifty years ago?

References

Rails Through the Clay, by A. A. Jackson and D. F. Croome. Allen & Unwin, 1962

The Story of London’s Underground, by J R Day. London Transport, 1969