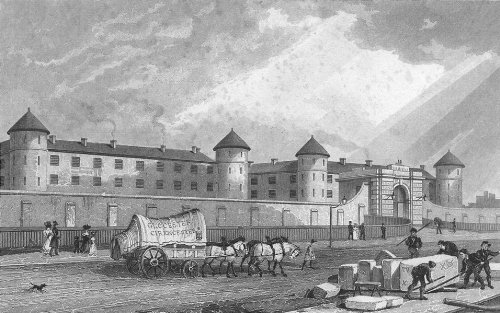

Millbank Penitentiary from Illustrated London, or, a series of views in the British metropolis and its vicinity, engraved by Albert Henry Payne, from original drawings. The historical, topographical and miscellaneous notices, by W. I. Bicknell. London: E. T. Brain & Co., 1846

Millbank, on the other side of the Thames to Vauxhall, takes its name from the mill belonging to Westminster Abbey. The mill stood on a lonely and marshy riverside road linking Westminster to Chelsea until it was demolished by Sir Robert Grosvenor who built a house there in about 1736.

The house was pulled down around 1809 and a prison (Millbank Penitentiary), designed by Jeremy Bentham, was built at a cost of £500,000 and finally finished in 1821. For a period, it was the largest prison in London.

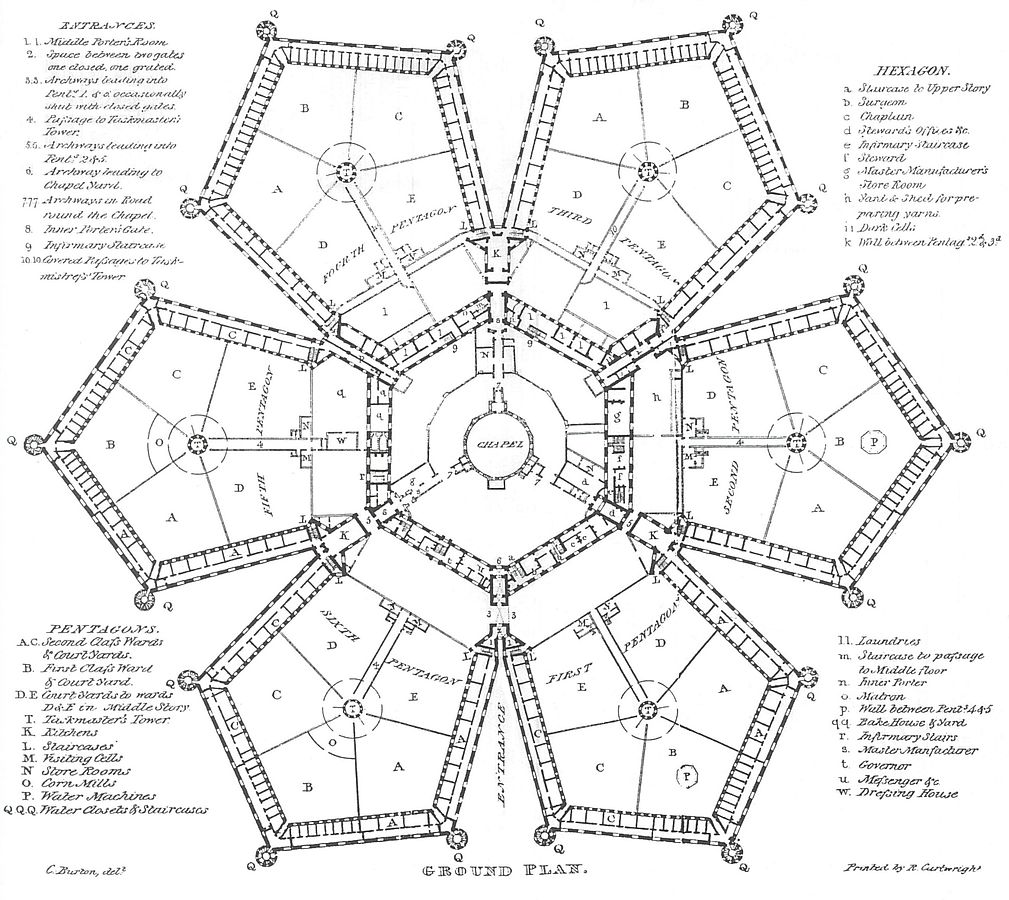

The prison walls formed an irregular octagon and enclosed seven acres of land. The layout was wheel-like with the Governor’s house in the centre, with six buildings radiating out to the outer wall turrets forming the spokes.

Millbank Penitentiary, 1829

It was a cold gloomy prison with a maze of passages totalling three miles in length. The prison was intended to house up to 1,000 transportation prisoners at any one time. Each had a separate cell and was forbidden to talk to any other inmate. Prisoners were forced to manufacture shoes or mail bags. The general conditions were very bad, with epidemics of cholera and scurvy in 1822-3 that affected half the prison (30 died). The average stay was for about three months which allowed staff time to decide on the destination for each prisoner.

All Great Britain and Ireland transportation prisoners were processed through Millbank with about 4,000 passing through its walls each year.

In 1843 it was converted to house general prisoners and later it held military prisoners. It was closed in 1890 and pulled down in 1902 to make way for the Tate Gallery.

It was only when Thomas Cubitt started developing Pimlico in the 1820s that the area was built up. In David Copperfield, Dickens mentions that the area was mainly “a melancholy waste”:

“A sluggish ditch deposited its mud at the prison walls. Coarse grass and rank weeds straggled over all the marshy land in the vicinity. In one part, carcasses of houses, inauspiciously begun and never finished, rotted away. In another the ground was cumbered with rusty iron monsters of steam-boilers, wheels, cranks, pipes, furnaces, paddles, anchors, diving-bells, windmill-sails and I know not what strange objects accumulated by some speculator and grovelling in the dust underneath which, having sunk into the soil of their own weight in wet weather, they had the appearance of vainly trying to hide themselves.”

Tradescant Road and South Lambeth blog has an interesting piece on the history of Millbank, including an aerial photograph of the building, taken from a balloon on 9 May 1891.