This article appeared in the March 1982 edition of The Vauxhall Society’s Newsletter.

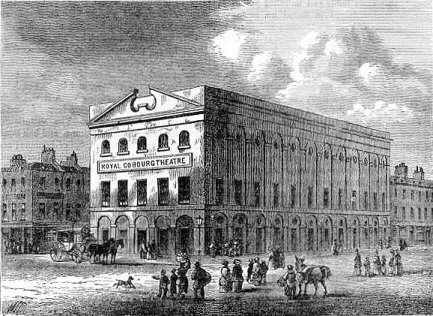

The Coburg Theatre, later renamed the Old Vic

In May last year [1981], our best-known theatre, the Old Vic, went into liquidation with debts of £400,000. The closure was a direct result of the Arts Council’s decision to withdraw its grant (the National Youth Orchestra and D’Oyly Carte Opera were other famous names which suffered a loss of support).

The Old Vic has lived through many vicissitudes of the battle to keep live theatre going in the face of penury, and it is probably not finished yet. Its foundation as the Royal Coburg Theatre in 1818 was followed by years of struggle to attract audiences even though the recently opened Waterloo Bridge made access from the West End much easier. In those days the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, and the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, had completely exclusive rights to perform ‘legitimate drama’ – in effect, any work of literary or artistic merit. Other companies’ productions regarded as too similar to theirs were immediately threatened with prosecution: so the Coburg had to rely on melodramatic spectacles, harlequinades, pony races and aquatic effects. As the surrounding neighbourhood developed its predominantly industrial character, its audiences grew more in numbers though very much poorer.

The Theatre attempted a re-launch in 1833, renaming itself the Royal Victoria, and was in fact visited by the young Princess shortly after the event. But the revival soon led into a period of decline, alleviated somewhat by the passing of the Theatres Regulations Act of 1843. The Act removed the monopoly of the Theatres Royal, and allowed the Royal Victoria, shakily at first, but in the end triumphantly, to mount productions of Shakespeare’s best loved works.

Another renaissance, this time in a completely different guise, took place in the 1880s. The Old Vic, as it had come to be known, was by then a centre of rowdyism, drunkenness and vice. Its financial collapse provided a group of radical philanthropists, led by Emma Cons, with a chance to start an ambitious project in practical moral reform. With her friends, Emma Cons had formed the Coffee Music Halls Co. Ltd, to provide ‘purified entertainment’ for working people without the usual intoxicating drink. She found wealthy backers, including the manager of the Gaiety Theatre, John Hollingshead, and on Boxing Day 1880 opened the Royal Victoria Coffee Hall in the modified and redecorated Old Vic premises. Standard variety acts, ‘tidied up’ to suit the new proprietors, were interspersed with intervals for tea and sandwiches. Thursday was ‘ballad evening’ and Friday a lantern slide show.

Once more, the Old Vic struggled, and after little more than a year Emma Cons’ company was in financial difficulty. This time, the clothing and woollen magnate, Samuel Morley, came to the rescue, and the great adventure in working-class adult education began, with series of public lectures in the theatre alternating with dramatic productions. In time the students at these lectures formed the nucleus of what is now Morley College, named after their original patron.

The story of the Old Vic in the 20th century, in some ways as chequered as in the 19th, is beyond the scope of this article. But the point has been made: the theatre has seldom found it easy to keep going, though its spirit never seems to die. Let us hope that spirit will revive once more to carry on providing dramatic entertainment for the people of London. Or perhaps the spirit is alive and well, but in keeping with its popular origins has simply moved across the road to the Young Vic? Even since this article was written, the ‘Old Vic’ has re-opened, albeit briefly, for the annual presentation of ‘Toad of Toad Hall’.