Malcolm Green was there in the 60s and 70s when the Council demolished more streets of Victorian terraced houses than the Luftwaffe – all to make way for soulless, isolating high-rise flats, desolate and dangerous open spaces resulting in widespread social breakdown.

Slum clearance started as a social movement in the 1920s and 30s with the aim of replacing unsatisfactory, overcrowded and unsanitary housing with modern accommodation. It was fuelled by government grants, and a side objective of giving employment during the depression. This led to the demolition of Victorian properties, some of low grade, particularly tenement blocks, but also to the wholesale demolition of many streets of terraced Victorian houses, including the streets between Hartington Road and the Wandsworth Road.

Hartington Rd SW8 in 1907. Most of the left side of the street was demolished as slums in the 1950s

Architecturally it was driven by the principles of Corbusier who advocated consolidating accommodation into flats surrounded by green open spaces for recreation and communal activities. His iconic building was the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, copied across Europe. The resulting proliferation of high-rise blocks of flats across our cities had unintended consequences. Firstly the demolition of streets caused the breakdown of longstanding social networks. Secondly the housing density of the flats was generally less than that of the Victorian terraces. Thirdly the open spaces became areas of desolation and danger since no one had considerate ownership of them. Finally the flats led to isolation and unhappiness compared to the sociability of street living.

Unité d’Habitation, Marseille

Following the 1939–45 war slum clearance was taken up again. For reasons that are not clear, the Victorian practice of having WCs at the rear of the property or in the yard was considered old fashioned and unsanitary. Terraces were declared “unfit for human habitation” by the Local Council Medical Officer, who generally walked (or later drove) down the streets without inspecting the houses internally. Large areas were designated for clearance, so that properties fell in value and the only purchaser if one fell vacant was the council, who could buy at a distressed price. These properties were left to decay, or were boarded up, thus exacerbating the downward spiral of the area, so that the compensation value on eventual compulsory purchase was low.

Terraced streets, and indeed whole areas, were demolished, often with little idea as to what should replace them. The destruction due to slum clearance was hugely greater than anything inflicted by the Blitz. By the 1960s the disadvantages of high rise increasingly acknowledged, so cleared areas were turned into new design lowish-rise houses or flats, left as open spaces, or used for schools or offices. Some of the cleared areas have only been built on in the last decade or two. Part of the problem was that while purchase and demolition were relatively cheap (and supported by government grants) there were insufficient funds for rebuilding, particularly as it became clear that earlier concrete structures had short lives.

I became involved in the issue of slum clearance because with my wife Julie I owned 5 De Laune Street, part of the “Braganza Street Slum Clearance Area” behind Kennington tube station, stretching from Ambergate Street in the north to Kennington Park Place in the south and comprising some 200 Victorian terraced houses of 3–4 bedrooms each and designated for demolition by Southwark Council in about 1967. During this time, I was a junior doctor at St Thomas’s Hospital. By 1970 about a third of the houses were owned by the Council and boarded up. There was no market for the remaining houses, other than the council.

5 De Laune St SE17

A small group of residents, led by Toby Eckersley, formed a task force to fight the demolition order. We were represented at the public enquiry and demonstrated that the medical officer on whose signature the houses were deemed “unfit for human habitation” had never entered any of them. We also argued that the cost of demolition and rebuild was six times greater than the cost of refurbishing the houses (refurbishment costs would fall largely on private owners rather than the public purse). The Inspector rejected both arguments: the former on the grounds that in his opinion the houses were indeed unfit (even though he also had never been inside any) and the second on the grounds that funding was “not a relevant consideration”. Our barrister advised us that the latter point was correct, but we appealed to the High Court nevertheless.

A grade 2 listed “short life” house after 40 years ownership by Lambeth

The High Court rejected our appeal on the grounds that longstanding case law stated that public bodies were not required to consider finances when proposing such schemes. The case would have rested there and the houses would have been demolished, were it not for Desmond Keane, a young barrister living at 23 Lansdowne Gardens. He heard our story, looked into

the case and decided it should be tested in the Court of Appeal, since it was against reasonable expectation that finances should not be a “relevant consideration” in public schemes. Thanks to his skill and the wisdom of the judges the Appeal Court decided that finances were indeed a relevant consideration and that the decision to demolish was therefore ultra vires.

This judgment has itself become case law [1]“In Eckersley v Secretary of State for the Environment (1978) the Secretary of State confirmed a compulsory purchase order for the acquisition of land to permit the clearance of slum properties, by … Continue reading.

Southwark Council backed off and the houses in Kennington still exist, have been refurbished, provide valued accommodation, and change hands for substantial sums.

The decision that demolition must be justified financially was the final nail in the coffin of Slum Clearance. However we live with the consequences of this well-meaning but flawed policy today. It shaped the urban landscape around us.

Lambeth also embraced Slum Clearance both pre- and post-war. Indeed Lambeth and Southwark were known as “bulldozer boroughs”. Lambeth bought up Victorian houses when they became vacant under their so-called “Short Life” scheme (“short life” as they were soon to be demolished). As recently as 2000 Lambeth still owned some 2,000 properties across the Borough bought in the 1960s under this scheme. These have been slowly sold off over the last decade, although there are still scores remaining in Council ownership.

Viceroy Road and Lansdowne Green Estate 2010

After WW2 Lambeth demolished the streets between Hartington and Viceroy roads and the Wandsworth Road to build the Lansdowne Green estate, which opened in the mid 1960s.

Thorne Rd in 1922

In the 1960s the area to the north of Thorne Road including the Victorian terraces on the north side of Thorne Road were designated as slums, and demolished in the early 1970s. The area south of Thorne Road was next in line, but was saved by the bell. In 1968 this area was designated as the Lansdowne Conservation Area, and by the late 70s many of the houses were listed grade 2. Now, demolition would be a criminal offence!

Thorne Road, 2012: Terraced housing on one side

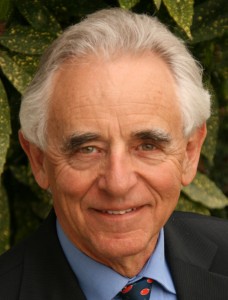

Malcolm and Julie Green

Malcolm and Julie Green

Malcolm qualified as a doctor at Oxford and St Thomas’s Hospital. After training posts and a research period at Harvard he was appointed a consultant physician to St Bartholomew’s and Royal Brompton Hospitals in 1974. He converted as a full time respiratory specialist to the Royal Brompton in 1986 where he remained until retirement from clinical practice in 2006. He was knighted for services to medicine in 2007.

Malcolm and Julie lived in De Laune St, Kennington in the late 1960s before buying a house in Hartington Road, Stockwell, in 1969. They moved to Lansdowne Gardens in 1973 where they have lived since, and are now among the longest standing residents. The house was in a state of disrepair when they bought it, with a closure notice on the semi-basement and two flats in the upper floors. They carried out considerable refurbishment then and have since restored the fine friezes and other features to their former glory.

References

| ↑1 | “In Eckersley v Secretary of State for the Environment (1978) the Secretary of State confirmed a compulsory purchase order for the acquisition of land to permit the clearance of slum properties, by virtue of powers contained in Part 3 of the Housing Act 1957. It was decided that the confirmation was ultra vires on the ground that there was a failure to take into consideration comparative costs of demolition and rebuilding.” (Introduction to administrative law, Hawke N, Parpworth N, Cavendish Publishing, 1998). (Full judgement available for legal eagles!) This decision had wide-ranging consequences beyond housing in that for the first time (!) it required public bodies to justify and be accountable for the financial implications of their policies. It seems inconceivable today that it could ever have been otherwise. |

|---|