If you had been with Frederick Austin the day he was left for dead on the Somme might you have helped him struggle free of a heap of English and German corpses – or might you have been one of them?

If you had been with Frederick Austin the day he was left for dead on the Somme might you have helped him struggle free of a heap of English and German corpses – or might you have been one of them?

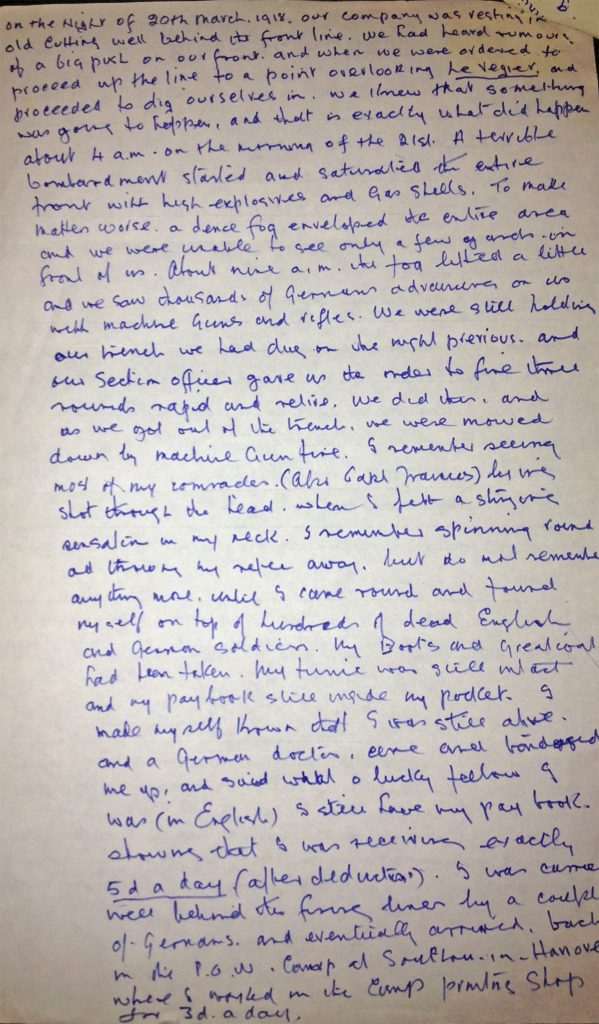

Sapper Frederick Austin was shot through the neck on 21 March 1918 in the opening hours of the massive surprise German infantry, artillery (and poison gas) assault on a weak part of the Allied line, the Somme sector. The bullet went right through Austin’s neck, but just missed his windpipe.

Austin, from Northfleet, Kent, missed the first battle of the Somme. When that began in the last week of June 1916, he was otherwise engaged in the Egyptian campaign, until evacuated home with dysentery. On 21 March 1918, however, Sapper Austin found himself in the path of the overwhelming German attack that marked the first day of the second Battle of the Somme.

At 4am on 21 March, a ‘terrible’ bombardment began, saturating the British line with high-explosive and gas shells. A dense fog then set in, so dense – Sapper Austin tells us – that he could see only a few yards ahead.

This was the start of the Germans’ last offensive on the Western Front, the one in which Wilfred Owen died, and was to inspire WWI veteran R.C. Sherriff’s elegiac play Journey’s End (1929). The German offensive was to end in their being chased back to the Rhine, surrender and revolution. The biggest defeat in German military history thus far, it was also the British Army’s greatest victory, ever. On 21 March 1918, however, it didn’t look like that.

On the night of 20 March Sapper Austin and his comrades of 104 Field Company Royal Engineers were ordered forward from their position in a railway cutting safe in the rear. They dug in overlooking a section of the front rumoured to be in the path of a big German ‘push’.

About nine a.m.,’ Sapper Austin writes, ‘the fog lifted a little and we saw thousands of German advancing with machine guns and rifles [….] our section officers gave us the order to fire three rounds rapid and retire. We did this, and as we got out of the trench we were mown down by machine gun fire.

I remember seeing most of my comrades (also Captain Francis) lying shot through the head, when I felt a stinging sensation in my neck […..] but do not remember anything more until I came around and found myself on top of hundreds of dead English and German soldiers.

My boots and greatcoat had been taken. My tunic was still intact and my paybook still inside my pocket. I made myself known that I was still alive and a German doctor [….] bandaged me up and said what a lucky fellow I was (in English).”

From Sapper Austin’s account, it seems as though his was one of the many mounds of corpses, British and German, that later in the day the Germans ‘cleared up’, stacking them in heaps for removal and burial.

Battle of Estaires. A line of British troops blinded by tear gas at an Advanced Dressing Station near Bethune, 10 April 1918. © IWM

But this ‘corpse’ came to, and crawled down the heap of bodies and to many more years of life.

Sapper Austin’s Army pay in 1918 was fivepence (2.5p) a day, twopence more than the Germans were to pay him for working as a printer in the prison camp.

Sapper Austin was repatriated on Christmas Day 1918, the Armistice having been signed on 11 November. He spent the next two years in hospital.

THE VAUXHALL CONNECTION

THE VAUXHALL CONNECTION

Sapper Austin’s eyewitness account is one of some 900 personal testimonies of the first day of both the 1916 and 1918 Somme battles. Originally collected by Martin Middlebrook for his ‘vox-pop’ histories, The First Day on the Somme (1971) and The Kaiser’s Battle (1983), the papers have come to light in Vauxhall, and now, in Armistice month, you can see these eyewitness accounts for yourself at the Imperial War Museum at Kennington.

The collection is being donated by supporters of Felix Fund, the bomb disposal charity, which is based with 11 EOD (Explosive Ordnance Disposal) Regiment, Royal Logistic Corps, at Vauxhall Barracks, Didcot.

The Somme papers came into the family of the late Holly Angharad Davies BEM, who was Vauxhall-born and as Chief Executive devoted the last years of her short life to raising money for the fledgling Felix Fund for bomb disposal personnel and their families.

Holly’s family wished the Somme eyewitness accounts both to have a suitable permanent home, open to the public and preferably near Vauxhall, and to raise money in Holly’s memory for Felix Fund’s Holly Angharad Davies Contingency Fund. Rather than to go to public auction and so risk the papers’ dispersal to private collectors, the papers were donated to the Fund. Supporters then donated a substantial sum, all of which went to the charity, and Felix Fund then gave the eyewitness accounts to IWM.

If you would like to contribute to the welfare of bomb disposal personnel and their families, contact Felix Fund citing the Holly Angharad Davies Contingency Fund.

IWM Documents.26137. IWM also has the Donald Hankey papers (IWM Documents.25410) with a letter and sketch of the turmoil in No Man’s Land on the Somme on 1 July 1916.