Edited version of a Vauxhall Society/Friends of Tate South Lambeth Library lecture on 1 July 2015 by David Toothill, Southbank Mosaics

I founded Southbank Mosaics in 2004, working alongside volunteers, with the twin aims of making mosaics of the highest standard with a strong social mission of supporting homeless people and working with young people in trouble with the law. By 2005 we had established ourselves as a Community Interest Company (not for profit, aiming to run as a business and create jobs, while working for our community’s improvement: a social enterprise) and began paying staff. We won our first major commission putting art work into some of Network Rail’s tunnels running out of Waterloo station.

“There have now been a total of five projects where Network Rail has worked with Southbank Mosaic. The results have always been spectacular, brightening up dark and dingy railway arches and tunnels… Southbank Mosaic are a leading example of involving local people in regeneration, particularly the more marginalised members of the community” Peter Marshall, Network Rail

We also partnered Lambeth and the Light at the End of the Tunnel team for many of our early projects. Since then this has been a well-trodden path for us; undertaking work which connects the public and private sectors with Southbank Mosaics acting as bridge. We were the first social enterprise in the construction business in the UK. We look at the surface of the built environment and imagine ways in which it can be enhanced. Mosaic is an architectural medium and there is a renaissance in its use to civilise and decorate public space, which Southbank Mosaics have supported. Situated in the crypt of St John’s Church, Waterloo, Southbank Mosaics now have over 250 installations in the world’s premier cultural estate, the Southbank, as well as in other locations in central London. These installations have been paid for by groups ranging from Transport for London, Network Rail, Brentford Market, Cleanology and the City of London Corporation.

Our work includes the world’s first memorial for homeless people who have died locally, situated in St John’s Churchyard Garden, Waterloo. This was built by homeless people whose names are included on the ceramic leaves of the installation. In addition we have installed an award-winning sculpture garden at St John’s churchyard which is tended by St Mungo’s volunteers.

Our work with young people in trouble with the law provides an alternative to custody for individuals on community service orders. We have worked with groups sent to us by the London Probation Trust and our Youth Offending Service, giving them a useful introduction to art and design, working alongside them to leave a permanent impression on the neighbourhood while supporting their rehabilitation through community engagement. We strive to share the highest quality of art with the dispossessed.

I wanted to deliver accredited courses to our students and in 2007 we became a registered training centre with the National Open College Network. In 2011 I heard Dr Will Wootton of Kings College call for a School of Mosaic and since that time I’ve been working with him to develop an accredited diploma and foundation degree course. We took this idea to a round table discussion at King’s College where the overwhelming response was positive. In 2014 we won an award from Social Investment Business to work with PwC and develop a Business Plan to this end. We also discovered there was no degree course in the UK in mosaic studies, and it appears there is none in the world which is odd for an art form that dominated Western and Islamic art from 400-1400 CE. Considering its architectural potential to respond to the minimalism of concrete and grass which dominates the British public realm, there is a good case to be made for artisan studios opening in towns and cities which want to link their streets to history, attract visitors and improve their profile. If the Arts & Crafts movement of the 19th century changed British interiors for good, then we are ready to train a generation of mosaic artisans to transform British exteriors for ever.

Another 19th-century programme – to build prisons – is also being questioned by our practice. The privatisation of prisons in America has seen the prison population grow to 1% of the entire country, over 2 million in gaol. We want to take a different direction. Prisons were built throughout the Victorian period as a response to moving away from use of the death penalty, with the continuing hope of reforming the offender. Our feeling is we now need a new movement to take us away from locking kids up behind bars. At Southbank Mosaics we have focused on the youth section of the criminal justice system, where the evidence is that 75% reoffend, up to 95% have mental health issues and 25% self-harm. Surely there are better ways: community responses, therapies, tagging, education training, for example what Southbank Mosaics does: exploring young people’s creative potential and ability to leave their mark on their neighbourhood in a positive way?

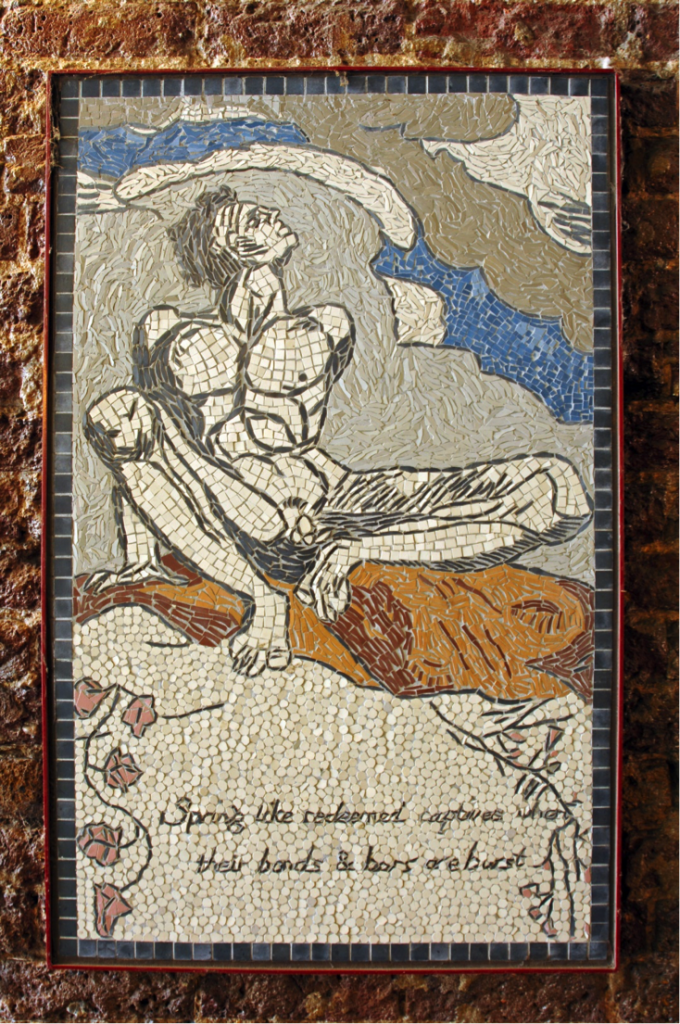

Our two most significant pieces of work to date have been 1. Blake’s Lambeth with 70 installations of mosaic interpretations of William Blake’s work in the tunnels leading out of Waterloo station and around Hercules Road, where Blake lived 1790-1800. This project is still on-going with 70 works of street art to date. 2. The installation of Queenhithe Mosaic in 2014 on the north bank of river Thames marking the port out of which modern London grew. Queenhithe Mosaic is a timeline, which uses time dated tiles collected from the Thames as a frame and has 164 panels depicting some of the highlights of the history of the dock. It is 30 metres long and our largest work to date.

When we first started working in North Lambeth we based ourselves in the Southbank area to help with the ubiquitous concrete in its public spaces. We were authoritatively told by the representatives of the major institutions to keep away from the main areas and concentrate on the by-paths, which we did – putting much of our work into tunnels and back streets. The Queenhithe Mosaic symbolises our acceptance, as we now have a prominent place on the river front, albeit the north bank.

We are currently pursuing two other projects, Shakespeare’s London and a display of the Shields of the Guilds. Gaining permission and support can take many years but we have shown we have the stamina and talent to achieve whatever task is set us. We are ready to work with other artists, architects and horticulturalists to re-imagine the public realm, link streets to their roots, put in fountains, seating and murals to build civic pride and delight visitors and employ artisans to make our neighbourhoods more attractive.

The definition of mosaic is a surface formed of discontinuous material and a form of art or decoration where small pieces of glass, stone or ceramics are inlaid to form pictures or patterns. The oldest mosaics come from Uruk in modern Iraq and date from the Sumerian times – at least 5000 years old. From there mosaic spread to the Mediterranean where it became established as a major art form, achieving remarkable heights in works in Pella (Greece), Pompei (Rome), Ravenna (Italy) and El Djem (Tunisia) among many other places and examples. For one thousand years it was the Western and Islamic world’s dominant art form, patronised by emperors, sultans, emirs, czars and popes. There is an incredible amount of mosaic, so much that it is largely left to look after itself and although durable, is certainly at risk of being lost.

In Britain there are 1794 ancient mosaics discovered and yet 80% of these have been re-buried, because that is our best way of preserving them. Thus the call by Kings College (London University’s Will Wootton) for a School of Mosaic.

Southbank Mosaic’s key focus has been to civilise and decorate public spaces today, so there seems to be three main reasons why the move towards establishing a School teaching the only degree course in applied mosaics in the world could prosper in London: 1.) Creating jobs in any neighbourhood, improving our public realm and making the environment more attractive; 2) preserving our history – which gives us a broader and deeper perspective on the achievements and failures of our past and thus a better informed opportunity to make life better in the future; 3) taking advantage of London as a major cultural centre with an outward-looking approach to knowledge and commitment to excellence.

David Tootill lives in one of the Coin Street Coops at the Southbank and is married with five children. Prior to setting up Southbank Mosaics David was a primary school teacher in Southwark “teaching everyone else’s children with no time for my own.”

“Setting up Southbank Mosaics allowed me to concentrate on things I enjoyed most: being creative, spending time with my family, improving my neighbourhood, working with community groups, and striving for excellence.”

“I’d first noticed mosaic as a student travelling in the summer in St Mark’s Square in Venice, then later in the Golden Temple in Amritsar. I wondered how could such beauty be possible outside and open to the elements? Mosaic seemed to me an ideal expression of our aspirations to live a better quality of life. Another “heaven on earth” was the Alhambra in Granada. If war and its consorts are the lowest aspects of humanity, then mosaic is its opposite and one of our highest achievements (along with music, fine art, architecture and horticulture). Mosaic is a metaphor for London – all its peoples, tribes, creeds, clans, colours, faiths and freedoms coming together to make a brilliant whole.”