Added 13 June 2015

By David Coke

The extraordinary commercial success of the re-launched Vauxhall Gardens in the middle of the 18th century encouraged other entrepreneurs to believe they could imitate it. Pleasure Gardens mushroomed all over London, around Great Britain, and then throughout the world. Most of these lesser ‘Vauxhalls’ were short-lived and, frankly, uninteresting, and have left little behind barring the name of the odd street and tavern in the area where they stood. A small group of these imitators, however, clustered around the original Vauxhall Gardens itself, like a brood of cygnets around the adult swan; because of their proximity to Vauxhall, and their close relationship with it, they have become an integral part of its history, and so deserve our special interest and consideration.

Detailed maps of small areas of London’s less exalted quarters from before the Victorian era are remarkably rare. For reasons that are not entirely clear the Vauxhall riverside is exceptionally well served in this respect, with at least three high quality maps being produced over a 170-year period. The first is the well known manuscript map of ‘Faux Hall Manour’ created by Thomas Hill in 1681; the purpose of this plan was to map the property of Christ Church, Canterbury in south Lambeth, and to record the various tenants and rents payable. The area around Vauxhall Manor itself is so closely populated that Hill has to include an expanded detail of it at the lower left corner. Two copies of this map are preserved in archives today – one at Canterbury Cathedral, and the other in the British Library.

The last of the three, dating from 1859, is not strictly a map, but a bird’s-eye-view. It is at the lower left corner of a large illustration in the London Illustrated News of 9 April called ‘The West End Railway District, London.’ In the foreground is Vauxhall Bridge, its eastern end surrounded by a very detailed view of all the streets and buildings on the site at that time (fig.1). Vauxhall Gardens, in its final season, can be seen at the lower left corner, to the left (east) of the railway line.

Fig 1: ‘The West End Railway District, London from the London Illustrated News of 9 April 1859, showing Vauxhall Gardens in the lower left hand corner

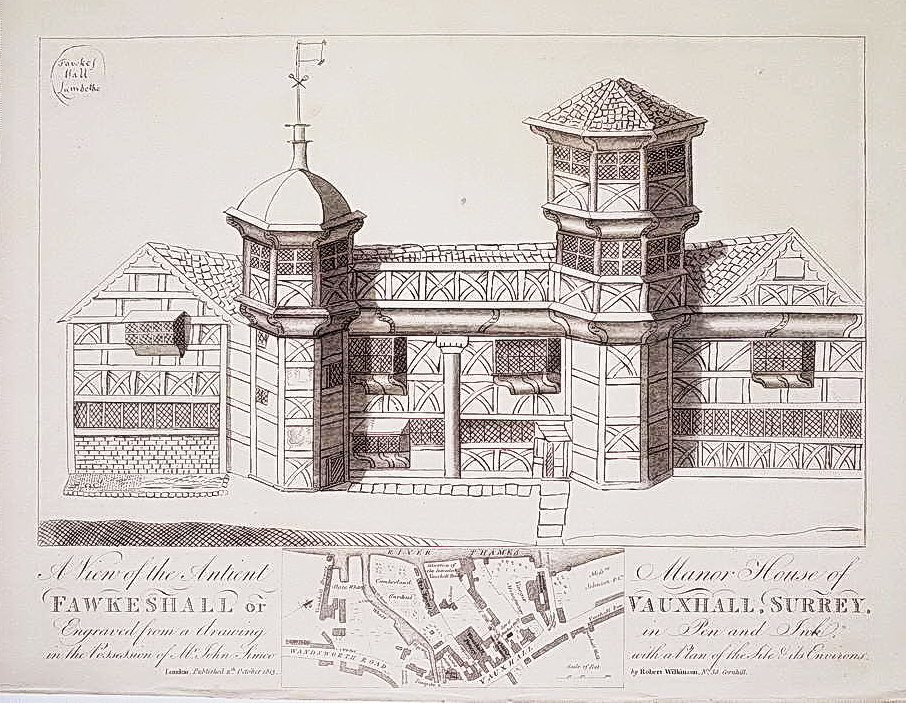

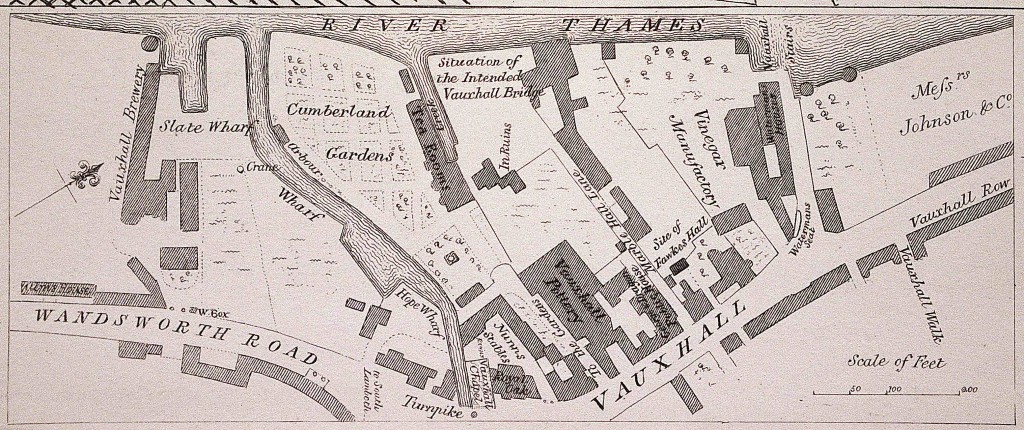

Between these two important historical documents is a third and more obscure map. Because of its up-to-date and minute detail, it is just as important and just as interesting as the others, despite its tiny size. It appears, almost as an afterthought, in an anonymous print called ‘A view of the Antient Manor House of Fawkeshall or Vauxhall, Surrey,’ engraved in 1813 from an old drawing then in the possession of a book dealer and antiquarian called John Simco (c.1750-1824) (fig.2); the main subject of the print is a large timber-framed house with two hexagonal turrets breaking out from the facade, and gabled wings at either end. Tucked in between the image and its inscription is the ‘Plan of the Site & its Environs’, showing where the house stood in relation to its immediate context. The print was published in 1819 by Robert Wilkinson as a plate in the first volume of his ‘Londina Illustrata’.

Fig. 2: ‘A view of the Antient Manor House of Fawkeshall or Vauxhall, Surrey,’ engraved in 1813

Measuring only 54 x 118mm, the ‘Plan’ from the print, which I am here calling the ‘Vauxhall Cross Plan’ (fig.3), represents a 180 x 425 metre section of the riverside area of Vauxhall at the beginning of the 19th century, and at the transition from working countryside to populated town. The plan shows what actually existed on the ground at the time, picking out individual buildings and features as small as the ‘Waterman’s seat’ where owners of Thames wherries would have waited until late in the evening for their passengers to return from Vauxhall Gardens or one of the other local attractions, to ferry them back to the opposite shore.

Fig 3. Vauxhall riverside, 19th century

Vauxhall Gardens, just outside the scope of the plan, was already more than 150 years old by the time this print was created, and was at something of a low ebb. Except for occasional special events and patriotic celebrations, fashionable society had abandoned Vauxhall Gardens. Only five years after this print was made, the garden was offered for sale, but no buyer could be found to carry it on, and rumours of its final closure were renewed every season. As we now know, these rumours were premature, and the gardens continued for another four decades, with some of their most profitable seasons, under new management and ownership, still to come; from 1822 onwards, by permission of the monarch, the gardens adopted the new name ‘The Royal Gardens, Vauxhall’, recognising the consistent patronage of several Princes of Wales since 1732.

The virtual monopoly that Vauxhall had enjoyed as a summertime evening entertainment had been broken many years before. Opportunistic entrepreneurs were opening pleasure gardens, many even called ‘Vauxhall’ and imitating its features, not only throughout London, but all over the country, and throughout the world. Even in Vauxhall itself, just yards from the venerable old Pleasure Garden, at least five new evening resorts were created. These are little-known today, principally because they suffer from a lack of visual and written documentation, which has kept them out of the history books.

The sites of three of these resorts are included on the Vauxhall Cross Plan. The ‘Situation of the Intended Vauxhall Bridge’ in the centre of the plan had, until c.1800, been Marble Hall Gardens. To the left of that the Cumberland Gardens are marked on the plan, and at the left edge, on the map’s compass point, would later be the Royal Brunswick Gardens, attached to Brunswick House (the building now restored and occupied by the London Architectural Salvage and Supply Company or LASSCO). These two latter sites, and the ‘Slate Wharf’ (owned by Mr. Frances in the 1840s) between them, are today largely covered by the St George Wharf residential development. The first Vauxhall Bridge, opened in 1816, its approach road obliterating what was left of Marble Hall; to its right (north), Burnett’s Vinegar Manufactory, and the site of Fawkes Hall are both now occupied by Vauxhall Cross, Terry Farrell’s MI6 building.

Though grandly named, Marble Hall had humble industrial origins. During the second half of the 17th century, it was part of the marble cutting mill and depot of Gerard Weyman, responsible for supplying much of the stone used in London for gravestones. The marble business had closed well before 1740, when an entrepreneur called Joseph Crosier advertised in the London Daily Post that he proposed holding evening assemblies at Marble Hall Gardens, for which he would charge 2s 6d for one visit, or £1 5s. for a season ticket. Even though we know that Crosier ‘enlarged, beautified and illuminated’ the gardens, and built a Long Room facing the river, for dancing, these prices must have been some of the steepest for any entertainment in London at the time. But the business prospered, at least into the following decade, when Nathan Hart, a teacher of music and dance, took it on as a summertime assembly. In the off-season he ran an academy on Essex Street in the Strand, where ‘grown gentlemen are taught to dance a minuet and country dances in the modern taste and in a short time.’ This remarkable polymath also taught music, fencing, European languages, navigation and mathematics. His teaching skills were put to use at Marble Hall as well, where gentlemen and ladies were taught to dance in private, partnered only by members of Hart’s family, before having to expose their skill (or lack of it) in public.

In its early days, Marble Hall’s Long Room gave it a huge advantage over Vauxhall Gardens, which was, at this time, an entirely open-air resort, subject to the weather and to the limited capabilities of outdoor lighting technology; this latter factor meant that, without a cloudless full moon, Vauxhall had to close around 10pm, when the reservoirs of oil in its lamps ran out. The Scots Magazine II, of June 1740, in telling its Scottish readership about the rich array of entertainments in London, reports that:

at Marble-hall, near Vaux-hall, a ball is established to relieve us from the necessity of coming home at ten; where parties bent on pleasure, may be favour’d with an opportunity of sitting up till day-light, amidst company enough to keep them awake.

And, no doubt keeping the whole neighbourhood awake too; in view of this, it is not surprising to find that Marble Hall became one of the many victims of the 1752 act to license places of public entertainment. Like many of its peers, it had to re-invent itself as a tea-house or coffee-house, and an advertisement of 1756, preserved in the Lambeth Archives (Lambeth Landmark, no. 10859) enumerates its new attractions; it had become an ‘ordinary’ (or restaurant) with ‘a continuous Supply of Hot Provisions’, but also with ‘private Subscription Assemblies’ for dancing (‘private’ so as to circumvent the licensing act). The Long Room could be hired for private concerts, assemblies, lectures or other events, and it was particularly emphasised that the riverside landing-place (for ferries and wherries) as well as the passage through to Vauxhall Gardens would be kept in good order, clean and well-lit, making it a more attractive approach to Vauxhall than the scrum at Vauxhall Stairs.

Marble Hall gardens were closed by 1800, and the site was cleared in 1813 to make way for the highway to Vauxhall Bridge. The dwelling house adjacent to the gardens, also called Marble Hall, is presumably the building to the south-west corner of the gardens, marked on the Vauxhall Cross Plan as ‘In Ruins’.

Just to the left of the ‘Ruins’ on the plan is marked a large ‘Tea Rooms’. This was the principal building, about 80 feet long, of the neighbouring Cumberland Gardens , the only one of these three riverside resorts that is delineated with any detail on the Vauxhall Cross Plan, and the only one that was fully functioning at the time. We see a dozen or more roughly rectangular areas of grass and trees, divided by a grid of gravelled walks; apart from the ‘Tea Rooms’, there are three small buildings, one ‘arbour’ on the southern walk, another in the northern corner, and a third at the eastern or inland end of the gardens fronting a large lawn with trees around the edge and a small structure, possibly an orchestra stand, in the middle. This plan appears to be the best surviving visual evidence for the layout of the Cumberland Gardens. A drawing of the interior of the Tea Rooms dated 3 August 1817 in the Lambeth Archives (Lambeth Landmark no. 1277) tells us little of the gardens apart from the fact that the room looks relatively smart, with many windows, a curved bar, and with a genteel and even fashionable clientele.

It appears that the gardens first opened in May 1774, when a Mr. Smith, possibly the same Mr Smith who was first Commodore (1775-1779) of the Cumberland Fleet (which in 1830 became the Royal Thames Yacht Club) advertised in the Morning Chronicle that he could accommodate parties up to a thousand strong, in his house and garden, then called Smiths Tea Gardens. His two main selling points were the situation of the garden on the banks of the Thames (‘which by nature is supposed to be unequalled’) and the excellent meals he could provide. He cannily emphasised the convenience of the site, close to Vauxhall Gardens; he hoped that ‘it will be found convenient for such companies as are going to Spring gardens or Vauxhall by water, to land there and drink Tea, &c. before going in, or supping, after leaving the said gardens; there will be a Cold Collation in the larder during the Vauxhall season.’ So Smith is actively exploiting the strictly-observed opening times of Vauxhall, as well as its notoriously mean and expensive refreshments.

The connection between Smith’s Tea Gardens and the Cumberland Fleet sailing club lay in the fact that the club would dine there following its sailing races on the river. The gardens were, conveniently, the finishing post for many such races. After their races, the contestants would require a more substantial feast than was available at Vauxhall, so Smiths Tea Gardens were ideal, even though the company would probably decamp to the larger gardens after supper for the superior entertainments there, and, occasionally, for the presentation of a cup to the winner of the race. The first of these cups was presented to the club in 1775 by the Duke of Cumberland, who also allowed them to use his name for the club. In the 1780s, these races had become such a popular spectator sport that they were appropriated by Vauxhall Gardens, which mounted special ‘Sailing Fetes’ on race days, with nautical themes in the music, the works of art, and the decorations. On these days, the Duke of Cumberland himself would occasionally take supper at Vauxhall, attracting huge crowds to see him. On 25 June, 1781, for instance, Vauxhall was permitted to announce that Prince Henry Frederick, Duke of Cumberland and Anne his Duchess would dine there that evening following the race; it is said that eleven thousand visitors flocked there just to get a glimpse of the royal couple.

Smith’s Tea Gardens survived the blow of losing the sailing matches, even continuing their own races, under the title of the Clarence Fleet, and mounting special events during the season. In 1779, for instance, playing Vauxhall at its own game, they advertised a ‘Fête Champetre, or Grand Rural Masked Ball’ to take place there on 22 May at 10pm, with an admission price of one guinea. However, five years later, Mr Smith had given up the gardens, and sold on the lease to an experienced and successful publican, Luke Reilly, who also ran the Freemasons Tavern in Great Queen Street. In the press on 18 May 1784, Reilly announced his proprietorship, as well as the change of name from Smith’s Tea Gardens to the Cumberland Gardens, capitalising on the tenuous connection with the Duke. Reilly continued his predecessor’s marketing techniques, continually pushing both the ‘Cool and refreshing situation’ beside the Thames, and the proximity to Vauxhall. Reilly’s advertisements draw attention to the walks, arbours and Tea Room. In the Autumn of 1792, Reilly offered his garden and its buildings as board and lodging for up to thirty French aristocrats ‘forced from their native land’ by the authoritarian and unpredictable republican regime at home. However, by the end of the century, the lease had been sold, and the garden’s clientele were becoming increasingly unfashionable and even local. When the lease was again offered for sale in 1803, having been rented to Mr Hodkinson, the gardens included a covered skittle ground and a billiard room.

Like Vauxhall, the Cumberland Gardens capitalised on Royal celebrations. To honour the wedding of Princess Charlotte of Wales and the Prince of Saxe Coburg in July 1816, the proprietors engaged a Herr Kraus from Danzig to create a ‘Grand Aerostatic Exhibition of a number of Beautiful Figures among which the Duke of Wellington on horseback larger than life, a Boar, a Dog, and a number of Balloons.’ These were presumably illuminated tableaux suspended below gas balloons. To accompany the exhibition and refreshments, the proprietors employed a military band that would play from the opening of the gardens at 12 noon.

By the time they were again sold, early in 1824, the pleasure garden aspect had been superseded by a less sophisticated image, and it had become The Royal Cumberland Tavern, still with an assembly room and tea-garden (with ‘gravel walks and flower beds . . . shaded by stately timber trees’), but with a newly built ‘tap’, or bar-room, to appeal to the expanding local population.

Even in the 19th century, the reduced cost and more generous measure of the refreshments at the Cumberland Gardens were a continuing problem for Vauxhall, especially for the waiters there, who earned all their income from serving food and drink; in the second decade of the 19th century, James Smith (b.1775) wrote in a memoir of Charles Dignum, one of the principal singers at Vauxhall, that he, Smith, had written a song for Dignum to sing at Vauxhall about the food, intended to ‘encourage the waiters, who complained that the company stole off, at twelve, to eat and drink in Cumberland-gardens, at a cheaper rate.’

Such, indeed, was the success and fame of the Cumberland Gardens that Warwick Wroth, the pioneering historian of the London pleasure gardens, numbers them amongst the sixty-four such places he includes in his 1896 book on the subject. He described the garden as small, ‘about one acre and a half in extent’, but ‘pleasantly situated’ on the riverside. In fact, they were almost surrounded by water, at least at the western end, with the River Effra to the south, the Thames to the west, and the Vauxhall Creek to the north, adjacent to the Tea Rooms. It is ironic that, though surrounded by water, the Tea Rooms were destroyed by fire. At about 4 o’clock in the morning of 25 May 1825, fire broke out in the building, destroying it within an hour, and leaving the gardens, according to the press, a ‘smoking waste’. The family living there were lucky to escape with their lives, and with the cash-box. The fire appears to have been accepted as an accident, although none of the Vauxhall waiters, returning home in the early hours, would have been without a motive for arson. The gardens were never re-opened, and Robert Bailey, William Knott and Catharine Gibbs, the last proprietors of the Cumberland Gardens, Vauxhall, were declared bankrupt in April 1827. The land was later occupied by the South Lambeth Water Works, who had installed a steam engine there by 1837 to pump water from the river; they were succeeded on the site before 1860 by the South Metropolitan Gas Company, whose Phoenix works were built on the site of the old Tea Rooms.

The site was no stranger to destructive fires, and it is one such that offers a solution to one of the little mysteries presented by the Vauxhall Cross Plan. Between the Cumberland Gardens and the Turnpike is a group of buildings including Mr Nun’s livery stables, the Royal Oak tavern and the Vauxhall Chapel, an independent chapel, only recently re-opened by its minister, the Rev. Thomas Gardner, which had acted at one time as an assembly room – it is marked as such on Stockdale’s New Plan of London (1797). Below the name ‘Nunns Stables’ on the Plan is a tiny and indistinct word, inexpertly added, and the Vauxhall Chapel is not blocked in with hatching like all the other buildings in the plan. Clearly some last-minute amendment has become necessary to keep the Plan up-to-date. Indeed, the drama is given in some detail by the contemporary press. The Annual Register of August 1813, relates that on the morning of the 12th:

at two o’clock a destructive fire happened at the house of Mrs. Morgan, fishmonger, near Vauxhall turnpike. It appears that the family had been ironing, and the fire, which was made on the hearth, there being no stove, caught the wood-work, and the premises were soon in flames. Mrs. Morgan had only time to make her escape by the roof of the house to the Royal Oak tavern. Another female on the first floor escaped, with a child in her arms, by getting on the leads.

The fire extended with great rapidity to the cheesemonger’s adjoining, which also is quite consumed. Vauxhall Chapel, which stood at the back of both, was also included in the conflagration. The proprietor of the Royal Oak tavern [Thomas Bayliss] was compelled to remove all his furniture, the fire having caught the corner of his premises, but fortunately the arrival of the engines prevented their destruction.

So, as the Vauxhall Cross Plan suggests, the Vauxhall Chapel had lost its roof, and was probably no more than scorched walls when the Plan was printed only two months later, and the two shops, which must have adjoined the west end of the chapel were mere ‘ruins’, unworthy even of being marked with walls. The Royal Oak, whose whole southern wall adjoined the chapel, had an almost miraculous escape. Allen’s History of Lambeth (1826), remarks that it had been described as having ‘galleries round it.’ In other words, it was a classic Tudor tavern with a galleried courtyard, almost certainly timber-framed. Its escape from destruction in 1812 was only a temporary reprieve, however; the old building was demolished to make way for the new road to Vauxhall Bridge, probably only a year later. The Bridge House inn, at no.213 Upper Kennington Lane, run by Richard Smith in the 1880s, occupied a site close to where the Royal Oak had stood, and appears to have been its direct successor (see the large house in fig.2 lower left corner).

The Royal Oak was not only the main venue for official local meetings, but it also had close connections with Vauxhall Gardens; it was the favoured hostelry of the Vauxhall musicians, and it was where they and the male singers held their annual summer dinner. It was also where Jonathan Tyers, the great proprietor of Vauxhall Gardens from 1729, chose to meet with his ‘Wits Club’ in the 1740s. The old Royal Oak has no discernible connection with the pub of the same name now at 355 Kennington Lane.

A little way to the north of the Royal Oak on the Vauxhall Cross Plan is marked the Vauxhall Pottery, the manufactory founded in 1683 by John de Wilde. This building was the main casualty of the new road to the bridge; however, the factory appears to have moved only fractionally, tucking itself in between the new road and the George and Dragon Public House on Marble Hall Lane – this pub being one of the few buildings (and businesses) on the site to have survived into the 20th century, finally falling to the demolishers’ hammers only in 1962. De Wilde’s pot-house flourished on its new site until 1865, producing tin-glazed earthenware and salt-glazed stoneware.

During the summer months, when Vauxhall Gardens were open, it was not unusual for several hundred watermen to be employed ferrying fashionable visitors to the south bank from London and Westminster; while their charges were being entertained at the gardens, the watermen normally had to await their return. This regular influx every evening during the summer provided a ‘captive audience’ for local taverns. It is no surprise to find that the Royal Oak and the George and Dragon were not alone in providing refreshments. The Vine, adjacent to the Fawkes Hall site (but not named on the Plan), competed with The Fox Ale House and the White Lion nearby, and with the Three Mariners on Fore Street, and The Pilgrim on Kennington Lane only slightly further away. The ‘Waterman’s Houses’ shown on the lane leading from Vauxhall Stairs to the high road of Vauxhall no doubt also provided more than bed and board for the men. Much of the spirits and the beer consumed in these premises was produced locally.

The whole of this site between Marble Hall Lane and Vauxhall Stairs (or Lack’s Dock) was occupied by the Pratt and Mawbey family for their distillery and vinegar works, taken on in 1810 by Sir Robert Burnett who continued the trade; in the 1920s it became a regional office and depot for the Anglo-American Oil Company (the predecessor of Esso). Today, of course, the MI6 headquarters designed by architect Terry Farrell stands on the site.

Returning to the south (left) end of the Plan, the ‘Slate Wharf’ next to the river Effra lay between the Cumberland Gardens and what was then the Vauxhall Brewery. Between the Brewery and the river is a small building of circular ground-plan that may be a windmill, several of which lined the south bank of the Thames. To the east of this site, between the area left blank on the Plan (apart from the compass point), and the Wandsworth Road, is a terrace of houses here called ‘Almshouse.’ Founded by Baron Noel de Caron from Flanders, an envoy to the English Court who lived locally, in around 1620, the alms-houses were not actually built until 1662, due to problems arising from Caron’s will. Occupied until 1852, they were then found to be in a dilapidated state, and demolished. The land on which the old building had stood was sold to Price’s Candle manufactory and the money used to build new alms-houses in nearby Fentiman Road in 1854. To the right of the alms-houses is marked ‘W. Box’, presumably a sentry box for the watchmen who patrolled this area.

This site on the left of the plan has a more exotic history than is suggested by the Plan. Immediately to the south (left) of the alms-houses was Belmont House, a fine Georgian house that was built on this site in 1758, and which, remarkably, still stands today, overshadowed by the modern towers of St George Wharf. The history of the house is well covered elsewhere on this website but what is less well-known is that Belmont (later Brunswick) House owned a substantial garden, part of which was opened in 1839 by a Mr. S. King as a small pleasure garden, taking advantage of the troubles of its larger neighbour at Vauxhall Gardens, which opened only irregularly in 1839, and not at all in 1840, because of the bankruptcy of its owners. It had been obvious for a few years that all was not well at Vauxhall, and several efforts had been made to sell it, but without success, so Mr. King, in common with other local entrepreneurs, thought it worth investing in a venture that endeavoured to fill the gap in the market. Sadly for Mr King, Vauxhall made an unexpected recovery, after which he could no longer compete.

While it lasted, though, the Brunswick Gardens enjoyed some success; a watercolour plan of 1844 in the Lambeth Archives (Lambeth Landmark no. 4549) shows a well-appointed garden right on the riverside. The orchestra is on the upper floor over the boxes on the south side. A single lawn is surrounded by a gravel walk, with two ranges of boxes on the north and south sides. An ‘Assembly Room’ was on north side, with a row of ‘Rustic Boxes’; there was also a bar, proprietor Mr Hodges. At the riverside was a covered promenade platform on piles over the river. A coffee house and ‘bun manufactory’ are marked as part of the south range of boxes. The length of the pleasure garden is only double the width of the house, so all the buildings must have been crammed in around the lawn. However, the admission price was just one shilling, and Mr. King’s garden was even able to imitate Vauxhall’s ‘Royal’ title, with the justification that the Duke of Brunswick, brother-in-law to the Prince Regent, had lived in part of the house for a couple of years from 1811, so presumably walked in the garden from time to time. Coincidentally, his son, Prince Charles, laid the foundation stone for the Surrey side of Vauxhall Bridge in 1813.

The Lambeth Archives hold a second document relating to the Royal Brunswick Gardens, which is a handbill (Lambeth Landmark no. 7340) of around 1840, announcing forthcoming concerts:

S. King, Proprietor of the above beautiful Gardens, once the resort of Royalty, has the pleasure to announce to his Friends and the Public, that, regardless of expense, and to satisfy the increasing taste for good Music, he has entered into arrangements with Mons. Laurent, Sen., Founder of the Promenade Concerts in this Country, for the purpose of giving Promenade Concerts D’Ete a la Musard et a la Strauss, on a magnificent scale, with a Band of Thirty Performers of first-rate Talent, both Native and Foreign. Under the direction of Monsieur Laurent, Jun. The Proprietor has the satisfaction to add, that in consequence of numerous applications, the celebrated Comic Singer, Mr. Howell, and several other first-rate Vocalists have been engaged. Composer and Musical Director, Mr. Blewitt. Admission, One Shilling, including a refreshment ticket – Children half price.” first concert on 6 July. The London and Westminster Steam Boat Co. would ferry visitors to and fro @4d.

The handbill includes a woodcut image of the gardens, as seen from the river, with a paddle-steamer just pulling up at the jetty. Steamboats had become a hugely successful and popular mode of travelling, and, with the new bridges, had effectively robbed the Thames waterman of their ancient trade.

Jonathan Blewitt (1782-1853) had been composer and organist at Vauxhall Gardens until 1839, and the younger Mons. Laurent had also been employed there – these were musicians of the highest calibre (and cost), and to employ thirty musicians as well as several singers must have involved Mr King in huge expense. This expenditure, and the very low admission cost (which included refreshments) are just two factors contributing to the gardens’ demise in around 1845. On top of this, Vauxhall returned to its old form in this year under the powerful and creative management of Robert Wardell, and the appalling weather during the whole season, which seemed not to affect Vauxhall, must have put intolerable strain on any business that did not have the firmest foundations.

The Brunswick Gardens clearly were no match for Vauxhall, and in 1845, a satirical print appeared in Punch (Landmark Lambeth no. 11617) showing the tumbledown buildings on site, with ‘To Let’ notices facing the river, and the caption:

Every true friend of the Constitution should rush to the Nine Elms Pier at Vauxhall, and see if anything can be done to save the House of Brunswick from a fate that is impending over it, or, from the river that is yawning under it. Patriotism may do much, but the plasterer can do more; and though the English enthusiasm may be of some use, we would rather put the House of Brunswick in the hands of a few stout Irish labourers.

Although the political message here is laboured and obscure (unless it refers to the prolonged absences of Victoria and Albert, whether in Germany or at Osborne House, and maybe even to the Chartist movement’s most popular leader, the Irishman Feargus O’Connor), it is clear that the neglected condition of the gardens is being equated with the equally vulnerable state of the British royal family.

In fact, though, it appears that fears for the state of the gardens were as unfounded as the political ones. The illustration of a small detail of the ‘West End Railway District’ from the Illustrated London News of 9 April 1859 (fig.4) shows the Brunswick Gardens still in place, with several of its original buildings. The garden can be seen between Belmont House (marked no. 40) and the river towards the top left corner of the image. By this time the house had become a club for railway workers. Beyond it is the huge arcaded building of the Nine Elms Railway Depot, and in front of it (towards the foreground) is the Brunswick Wharf, where slate can be seen piled up; in front of that, on part of the old slate wharf, is the factory of Price’s Candles (no. 39), and then, on the site of the Cumberland Gardens, the imposing neoclassical building that was the Retort House and coal store of the Phoenix Gas Works, just next to the road to Vauxhall Bridge which is itself on the Marble Hall site. Old Vauxhall Gardens, in its final months when this print was published, is off the left, not visible in this detail, but just included at the lower left corner of the complete image.

Fig 4: ‘West End Railway District’ from the Illustrated London News of 9 April 1859, showing the Brunswick Gardens still in place.

There is little more to be said about the Vauxhall Cross Plan; however, this article’s original purpose was to explore the smaller pleasure gardens of Vauxhall, and that story involves more of the area than just the riverside. Several London pleasure gardens were set up as a result of the discovery of springs of mineral water. Bagnigge Wells and Sadler’s Wells are two of the more famous ones, but Lambeth had its own spas as well, inland from the river. The full story of the Lambeth Wells is related elsewhere on this website, alluding to the spa set up in the reign of William and Mary, which developed in the 18th century into a concert room and dance hall; as with many such places, it was deemed, in the 1750s, to have become ‘a nuisance’ and even ‘a common brothel’, so lost its licence. Nothing daunted, though, it joined the nearby Marble Hall in becoming a ‘tea-garden’. It even managed to survive into the twentieth century as a pub called the Fountain, on the east side of Lambeth Walk, near the junction with Lollard Street, as it is today. Charles Knight, the prolific commentator on London’s culture, adds a little colour to the story of Lambeth Wells, mentioning in an article in the Penny Magazine of 16 December 1837 that, in order to attract popular favour, the proprietor of the Wells, not content with regular concerts, ‘advertised at one time a “grinning match” the successful competitor in the art of making hideous faces was rewarded with a gold-laced hat.’

However, the most ephemeral of the pleasure gardens set up around Vauxhall was actually the closest to it. The Royal Victoria Gardens, despite its noble title, lasted only three years, between 1837 and 1840. It lay on the eastern boundary of Vauxhall Gardens itself, two acres of the rectangle now occupied by five blocks of the Vauxhall Gardens Estate and bounded by St. Oswald’s Place (ex. Miller’s Lane), Tyers Terrace, Vauxhall Street and Kennington Lane. A watercolour plan of the Victoria Gardens is preserved at the Museum of London, showing the entrance on Miller’s Lane adjacent to a tavern. Entering the garden visitors would first see, on the left, a building marked on the plan as ‘Mechanical Figures’, next to the Assembly Room, with a stage to its right; to the south of these buildings was an area of flower beds, with a ‘Covered Music Stand’ in the middle; this overlooked a large area of lawn in the centre, which was bounded to the left by a serpentine row of ‘Rustic Boxes’ and a bar; opposite this, to the right, is a Refreshment Room; to the south of this entertainment area is a chapel on the left, and Mr Miller’s House, with Miller’s Nursery bounding Miller’s Lane; between Mr. Miller’s House and Kennington Lane is a terrace of private houses. The garden is described in a press notice announcing its ‘re-opening’ in 1837 [Guildhall Library, Fillinham Collection] as being ‘laid out with trees, plants, evergreens, paintings and decorations of various kinds, a new covered promenade 90ft long, brilliantly illuminated, an elegant dripping grotto, figures of brutes, China pagoda, Monkeys, mechanical figures, &c.’ Apart from the last four of these attractions, it sounds very like Vauxhall Gardens. It is likely that the Victoria Gardens was opened, like the Brunswick Gardens, in the expectation of the immediate demise of Vauxhall, whether by a competitor or by someone closer to home is not known. It may even have been waiting for its neighbour to close so that it could take on some of its staff, even some of its buildings. Its closure, in the same year as the bankruptcy of Vauxhall’s proprietors, its defiant closeness, and even its royal title all suggest that the two were linked by more than a boundary.

The presence of Vauxhall Gardens and its smaller satellites in south Lambeth is known to have contributed significantly to its development, its economy and its character. The gardens directly employed hundreds of seasonal staff, and were supplied with the raw materials for their refreshments and their infrastructure by local or regional suppliers; they were responsible for a boom in the number of watermen ferrying customers from the north to the south bank of the Thames; the gardens also created a tendency for musicians, actors, acrobats, firework-makers, artists, singers, dancers, and all sorts of entertainers to move to the district, giving it something of a Bohemian air even today. Vauxhall Gardens attracted residential development to the area, and eventually brought not only the Regents (or Vauxhall) Bridge across the Thames, but also the railway station to its doorstep, and it initiated a continuing tradition of nocturnal entertainment in an area that could otherwise so easily have been overrun by the spread of the light and heavy industries which had been monopolising and polluting much of the riverbank since the mid 17th century. The ‘Vauxhall Cross Plan’ is a vital piece of the jigsaw that relates the extraordinary history of this often forgotten district of London, and it shows just how much of the riverbank here remained green until well into the 19th century.

David Coke is co-author with Alan Borg of Vauxhall Gardens: A History (New Haven and London: published for The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by Yale University Press), 2011. This is an original article written for the archive.