The text of this page is based on two articles that appeared in the Vauxhall Society’s newsletters during 1983.

Stockwell tube station

In previous Newsletters we have described the history and architecture of some tube stations within the Society’s area. But the station at Stockwell, and former railway depot nearby (of which hardly a trace remains) are of particular interest both for what they were and what they might have been.

Like the stations at Kennington and Oval, Stockwell was originally opened as part of the first deep-level underground railway in Britain, and was owned and worked by the City & South London Railway Co. (CSLR). The Company had started life as the City of London and Southwark Subway, with plans to build a line, wholly in tunnels, from the north end of London Bridge to the Elephant & Castle. Power was to have been provided by a continuous cable, rather as the famous San Francisco tramcars are driven even to this day: the necessary Act of Parliament was passed in 1884.

New advances in electric traction during the 1880s, however, led to a change of plan before the line opened. The small rural village which had been the Stockwell of the 1860s had by then turned into a prosperous and fashionable suburb. The prospect of a regular commuter traffic into the City was seen as an even more valuable prize than the humbler folk of the Borough would provide. The new line was thus extended southwards and electrified throughout. Its terminal station at Stockwell was opened by Edward, Prince of Wales, on 4 November 1890 and opened to the public a few weeks later. The change of plan was a bold one, since operating conditions on the renamed CSLR were to be far more arduous than on any existing electric system at that time, and a completely underground electric railway was quite unprecedented.

At Stockwell the railway ended at an island platform, having tracks each side, and all fitted within a single 26-foot wide tunnel. The same kind of layout, now rare on the London underground, can still be seen at a few places such as Clapham Common and the Angel. Lighting in the station was originally by fish-tail gas-lamps.

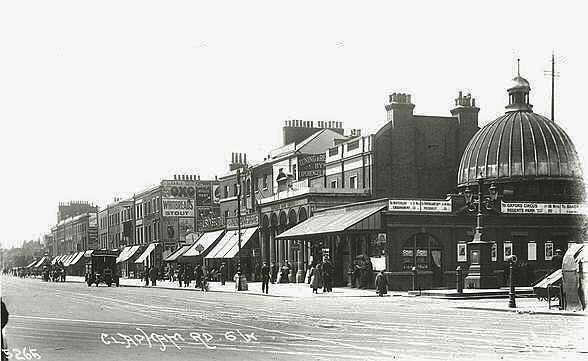

Stockwell Station, c 1918

As one approached Stockwell station from the north, a side tunnel branched off up an amazing 1 in 3½ incline – to reach the depot and workshops. These lay in the angle between the Stockwell and Clapham Roads, just south of Spurgeon’s Orphanage, on a site now occupied by council flats. Rolling stock for repair was dragged up the incline by chain attached to a steam-driven winding engine. This system gave trouble, however, and in 1905 it was replaced by a 20-ton hydraulic lift which could raise one passenger car or one locomotive at a time from the tunnel level to the surface.

Apart from the storage sidings for rolling stock, this depot contained workshops where trains were overhauled and in the 1890s, some of the Company’s own electric locomotives were actually built. The lifts at stations along the line were hydraulically operated by three 100-hp pumping engines at the Stockwell depot, and a compressor plant was also there to provide air for train brakes. Primitive though it now seems, at the end of each trip to the City, the diminutive CSLR locomotives had to recharge their brake reservoirs from a supply point in the Stockwell station platforms.

Finally, the depot contained the electric power station where three (later four) huge steam-driven dynamos fed current to the live rail at 500 volts DC. The equipment was modernised and enlarged in the early years of this century, as the CSLR extended both north and south of its original route and the service steadily intensified to as many as 28 trains per hour. In the early days, the depot steam engines chugging away each morning as rush-hour passengers poured into the lifts and trains, must have made an impressive and dirty sight.

Externally the Stockwell station was typical of the new line: a single-storey brick building designed by T.P. Figgis, surmounted by a handsome dome containing the machinery for two lifts. These lifts could each carry 50 people up and down the 45-foot deep shaft which connected the platforms with street level. Together with the station buildings they were swept away in the modernisation programme of the 1920s.

Stockwell Shelter

Although nothing now survives of the original Stockwell station buildings, a good impression of what they were like can be gained by looking at Kennington station. Stockwell station was initially a great success with its clientele and, to cope with increasing traffic, the railway company repeatedly had to order new carriages. By 1908 the fleet had grown from 30 of these “padded cells” as they were nicknamed (from their low headroom and absence of windows) to 170.

In the same year, the City & South London carried over 20 million passengers but, even so, could scarcely pay any dividend on ordinary stock. The reason for this poor financial performance was not hard to seek. Competition from the new motor buses and electric trams was severe along the CSLR route, and the rate of technological advance on the other underground electric railways, which now wormed their way under central London, made the pioneer line seem antiquated.

In 1912 the London Electric Railway Co. (LER), which had already acquired most of the rest of the London tube network, bought out the CSLR and began a programme of new investment. Stockwell’s traffic improved with the help of a publicity drive and coordination agreements with other train and tram operators, who offered through bookings to many new destinations.

From June 1915, the rather primitive generating machinery at the Stockwell depot was retired. In its place a transformer substation was built and fed from the parent company’s huge new power station at Lots Road, an arrangement which continues to this day.

The next major developments at Stockwell started as part of a programme of economic recovery in the early 1920s. During 1921 the number of unemployed rose to almost 2 million, and Lloyd George’s coalition government passed a Trade Facilities Act, designed to encourage programmes of works creating new jobs. The Chairman of the LER, Baron Ashfield, quickly took advantage of the new Act by putting forward a £6 million tube development scheme. At first, trains continued to serve the station while modernisation went ahead. Then, a train struck some building equipment inside the tunnel and the station was closed, along with others on the former CSLR, from November 1923 to December 1924.

During that year of closure, Stockwell station and depot were transformed. The depot became a working site, with most of the old buildings demolished and the original lift for raising rolling stock used to bring out debris and take down new materials. Out came the spoil produced as the tunnels were steadily enlarged throughout their entire length, in order to cater for new trains; in went steelwork and thousands of the familiar white tiles for lining station walls and passages.

The sidings at Stockwell depot became redundant after the connection with the Hampstead branch of the Northern Line was effected at Camden Town, as trains could now be stabled in the new depot at Golders Green. The workshops at Stockwell were also superseded by the new overhaul facilities opened in 1922 on the site of former market gardens at Acton. The original Stockwell station buildings were demolished and replaced by a spacious booking hall behind a new frontage clad in cream terracotta tiles with black dressings. The same effect was used at the rebuilt Oval and Clapham North stations (which still retain these features). The lifts were replaced by two reversible escalators, flanking a fixed stairway; the platforms were rebuilt in separate station-size tunnels and lengthened. The antiquated signal box was scrapped and replaced by a more modern power-operated system.

At the end of all these works, the depot site could be sold, and a journey from the re-opened Stockwell to the City was five minutes shorter: the ride, in brand new trains, was incomparably smoother and more comfortable So robust were these trains that when they were eventually withdrawn by London Transport in 1965, after subsequent service on other lines, a selection of the best were shipped to the Isle of Wight where they are still at work today.

The success of the modernisation was obvious: in the year after re-opening (1925) traffic increased 32%. Then followed a largely uneventful period, remembered chiefly for the transfer of ownership to the London Passenger Transport Board, formed in 1932. The popularity of the extension southwards to Morden gradually put more and more strain on Stockwell patrons, who increasingly found the trains over-crowded by the time they reached their station. In this overcrowding were the seeds of a scheme for an entirely new north-south deep-level tube railway, which was partially constructed in wartime and has never been completed.

During the heavy air-raids of 1940, many Londoners began using tube stations such as Stockwell as shelters. At first the authorities disapproved, but their view soon changed and arrangements for sanitation, feeding and even entertainment began to be provided. Plans were also drawn up, by the end of 1940, for the LPTB to construct at Stockwell (and nine other sites) a pair of large parallel tunnels beneath the existing tube stations. These tunnels are about 1400 feet long, 16 feet 6 inches in diameter, and were equipped as shelters for up to 8000 people each; their eventual purpose, in peacetime, was intended to be part of an express underground line, duplicating the Northern Line for much of its length and making fewer stops. Each shelter tunnel is divided horizontally to form upper and lower levels, and by transverse walls, to create eight separate dormitory or living areas. The accommodation is reached by shafts and stairs from the ordinary tube station above, as shown in the diagram. Access is also provided by two shafts direct from the surface, capped by concrete block-houses. These structures are visible in the centre of the traffic roundabout at the junction of South Lambeth Road and Clapham Road (beside the clock tower, and behind the end of the parade of shops a short distance south of Stockwell station entrance. The ventilation systems are designed against gas and smoke, and the electrical systems against failure from a variety of causes.

The Stockwell shelter was completed in September 1942, but was not finally opened for public use until 9 July 1944, after the assault by V1 flying bombs had begun. In the interim, the shelter was officially ‘held in reserve’, and probably used as billetting accommodation. By early 1945, it was closed to the public and used for a time as a transit camp for HM Forces personnel en route through London. London Transport, the nominal owners of the Stockwell shelter, maintained their option to use it for railway purposes until the early 1970s, when it passed to the Government’s Property Services Agency. Its present use is unknown. [2010 addendum: The shelter houses the Guardian newspaper’s archives, among other uses.]

The final chapter in the history of Stockwell station opened in 1967, when approval was given by Transport Minister Barbara Castle for construction of the Brixton extension of the Victoria line. The new tube, approaching from Vauxhall, was aligned to give easy interchange at Stockwell with the existing Northern line platforms. This interchange was seen partly as a way of improving travel tines from south London to the West End, but also as a relief to overcrowding on the Bakerloo and Northern lines north of Waterloo.

Construction of the Victoria line at Stockwell was difficult, due to the presence of water bearing gravel and the need to pass very close to existing tunnels without disturbing them. These works proved expensive and time-consuming with the result that the surface buildings were finished hurriedly to a simplified design. They consist of a plain brick elevation replacing the 1924 edifice, and enclosing an enlarged booking hall. This is finished in a functional, contemporary style, relieved by a mosaic floor which was specially laid by Italian craftsmen. Automatic ticket gates were installed and, rather unusually for a tube station, public lavatories, though these are now restricted to staff only [2010 addendum: these facilities have since been withdrawn]. From the booking hall, a third escalator was provided to reach the platforms, where the decorative tiles, by Abram Games, are representative of ‘The Swan’, a noted local hostelry.

The renewed Stockwell station now copes remarkably well with heavy wear and tear from its users, and in the 90-odd years since its opening has seen many changes. It has in fact been progressively rebuilt and extended to the point where very little of the original remains; the aim of this article has been to give some idea of what came before the structure we see today – and indeed the considerable part which we do not see.

References

A. A. Jackson and D. F. Croome, Rails Through the Clay

J. R. Day and J. Reed, The Story of London’s Underground

C. M. Harris, What’s in a Name? The Origins of Station Names on the London Underground

London Transport, The Brixton Extension of the Victoria Line

N. Pennick, Bunkers Under London

N. Pennick, Tunnels Under London