Every year in the UK, around Bonfire Night, about 500 children under the age of 16 end up in hospital A&E departments suffering from firework injuries. Many of these youngsters will be scarred for life, for most of the burns are to eye, head or hands. In Victorian times, Vauxhall Gardens was a favourite showground for firework displays and by the middle of the 19th century, the surrounding area of Lambeth and Southwark was home to numerous makeshift firework ‘factories’. David E. Coke lifts the lid on the terrible human cost of this explosive, unregulated local industry.

Life was precarious in mid-Victorian London, nowhere more so than in the south London boroughs of Lambeth and Southwark. This unflinching article, not for those of a sensitive disposition, commemorates the horrific deaths of two little girls, caught up, through no fault of their own, in a shocking catastrophe on an ordinary day in an ordinary London street 165 years ago.

It was on a calm summer evening in 1858, during the heatwave that helped to create the ‘Great Stink’ of the partly dried-up river Thames, that the tranquility of Southwark in south London was suddenly and shockingly shattered by a series of terrifying explosions. In fact, The Belfast Newsletter of 15 July reported breathlessly that the noise ‘could only be likened to some convulsion of nature; for miles round, the houses were shaken to their very foundations’. Was this an act of war, or a piece of new technological discovery gone horribly wrong? Locals probably knew exactly what it was, and had been expecting something like it for a while – the local fireworks factories were well known and widely dreaded.

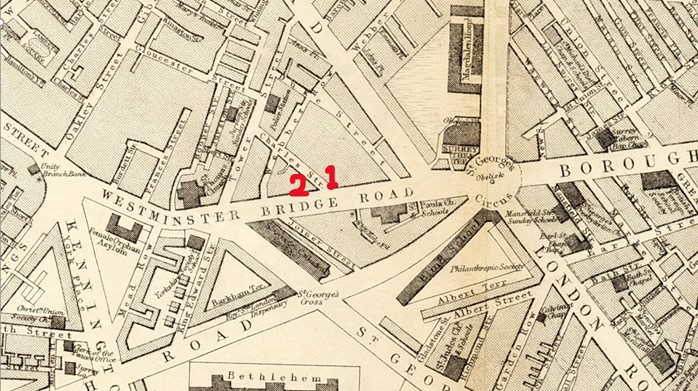

Even though it was one of the most lethal and damaging event of its kind, the accident at Madame Coton’s fireworks factory on 12 July 1858 was by no means the first time this had happened in that area, or indeed to Mme Coton, whose factory had already suffered three fires. Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper of a few days after the explosion stated that ‘this very house [Mme Coton’s] had already been three or four times destroyed. Yet, the wreck cleared away – more gunpowder was calmly brought into the Westminster-road, to be elaborated into catherine-wheels and rockets’. It was said that the scars and chips on the obelisk in the middle of nearby St George’s Circus are the results of several local firework factory explosions. [Fig.1] Nor were these lethal accidents restricted to London – just six months before Mme Coton’s factory exploded, Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper of 7 February 1858 reported a similar incident two days earlier at George F. Bywater’s firework factory in Sheffield, Yorkshire, which resulted in three fatalities.

The press, whether local, national or indeed international, covered the 1858 incident and its consequences in lengthy detail. A letter was published in The Times five days after Mme Coton’s disaster, from somebody called Watson who says that he was ‘more acquainted with firework makers than the generality of people’. He had told a friend that he had been to Vauxhall Gardens one day when he thought the fireworks rather poor – ‘Why, what can you expect at the prices they pay for them?’ said his friend, adding, ‘Madame Cotton cannot afford to pay a proper workman; she has nothing but boys and girls. We shall hear of another blow-up before long.’ The letter then continued in rather more technical terms: ‘To intrust boys with the preparation of crimson stars is madness, containing as they do so much chlorate of potash and sulphur that friction alone will inflame them.’ Jack Watson (possibly related to the letter-writer), one of Mme Coton’s three boys, was paid three shillings a week at a time when adult workers in similar semi-skilled trades would be earning up to ten times that sum. Jack and his two young colleagues had been only recently employed by Mme Coton while the demand for fireworks was at its height.

The Daily Telegraph of 14 July, spoke for many when it asked, ‘How many fire-work factories are there in the metropolis? Where are the next hundred persons to be burnt, scorched, flayed, and put in danger of their lives?’ It went on to say that north of the river, most nuisances had been cleared away, yet London’s streets could still ‘explode without an instant’s notice, to shake the foundations of houses for miles round, to scatter a scalding composition through entire streets, and to crowd the hospitals with blackened victims, mutilated, scalped and disfigured for life’. And in the most evocative and emotional of all the reports of the 1858 incident, the writer endeavoured to describe the horror of Mme Coton’s disaster in words: ‘Here a child had the flesh seared from its back; there a policemen was blown down under the hoofs of a panic-stricken horse; in one direction a man’s hands were so suddenly consumed that the ligaments parted from the bone; in another a young girl was stripped of her clothes in the midst of a flaming whirlwind.’ He aptly compared the scene, with all its smoke, fire, din, flying timbers and scorching rubble, to being on the gun-deck of a man o’war at the height of battle.

Mme Coton herself (born plain Frances Tucker in Lambeth on 25 January 1824) had been brought up in the fireworks trade – her father Edward Tucker called himself an ‘Artist in Fire Works’, and she had been previously married to William Coton, of Bird Street, Vauxhall, another firework-maker, so she was thoroughly immersed in the industry; even though her first husband, whose name she kept, died young, most likely in a work-related incident in 1854, it is no surprise that she chose this as her career, and involved her second husband, William Bowyer Bennett (16 August 1829–2 April 1909) in her trade as well.

Possibly because of its proximity to both Vauxhall and Cuper’s Gardens, the Westminster Bridge Road area had become home to several firework producers in the 19th century. [Fig.2] Sarah Hengler had been based at Asylum Buildings on the Westminster Bridge Road, just west of St George’s Circus; Samuel Drewell was more or less next door, and Mme Coton and Henry Gibson (previously known as Cannon) lived and worked opposite to them. In nearby Lambeth, several more pyrotechnicians, including H.W. Darby, and J.G. d’Ernst, both working for Vauxhall Gardens among others, had set up shop. Since the turn of the century, the demand for firework displays, whether private, public or royal, had risen exponentially, and there were always people willing to risk their lives, both in the manufacture and the display of fireworks, for the rich rewards on offer. But it was acknowledged to be a dangerous trade; both Sarah Hengler and John D’Ernst had died in explosions, on 9 October 1845 and 28 February 1842 respectively, and Darby’s workshop at 5 William Street in Lambeth had exploded on the very morning before Mme Coton’s incident, only to be moved just around the corner to 98 Regent Street (today called Courtenay Street). Unlike other such events, however, Mme Coton’s explosion was widely reported, not just in London newspapers and periodicals, but around Britain, and internationally too.

Madame Coton, the stage-name of Frances Ellen Bennett (eldest daughter of Henry and Hepzibah Tucker), who was in charge of the fireworks at Vauxhall and Cremorne pleasure gardens in the 1850s, normally used her home at 4 Elizabeth Place on Westminster Bridge Road for the less dangerous stages of her manufacture, and for finishing the pyrotechnics that had been manufactured at her Peckham factory. Her house was on the eastern corner of the junction (nearest St George’s Circus) between Charles Street (now Gerridge Street) and the Westminster Bridge Road, on the north side of the main road more or less opposite the church and school of St Paul’s (now the St George’s RC Primary School; St Paul’s Church survived the explosion, but was destroyed by German bombs in 1941). Mme Coton lived at the house with her husband, William Bowyer Bennett (they had married on 24 November 1855), their servant Hannah Welsh and a little girl who was named as Caroline Bridges in the Morning Chronicle of 14 July. Further up Charles Street, a few houses away from Coton’s, was Mr Sumpter’s house, used by Mme Coton as an additional store and factory.

It appears that the week of Monday 12 July that year was to be especially demanding for Mme Coton and her team. Having been closed all the previous year, Vauxhall was open every day except Saturday in the 1858 season, and a ‘Grand Juvenile Fete’ was due there on the Thursday, for which fireworks were essential; the Bennetts had been fully occupied since the previous Monday in building up a good stock for Vauxhall’s displays. The result was that the house at Elizabeth Place had become a staging-post and storehouse between the Peckham factory and the Gardens.

There is little doubt that it was Mme Coton, not her husband, who was the driving force behind the business – her word was law. William Bennett is known to have transported fireworks to the performance venues, and he may also have done a certain amount of administrative work but he had little to do with the actual manufacture or display, and in one judge’s words was little more than a cipher. Mme Coton was reported by her 30-year-old foreman, Edwin Tucker (possibly a relation, who said he had been an ‘artist in fireworks’ all his life) to be a self-willed woman, someone who would not take orders from anybody, and who only asked someone’s opinion to ignore it; ‘she was master and mistress both’ in the household and the business. Tucker grumbled that ‘she has called me a fool many times.’ Appropriately for a pyrotechnician, she was clearly something of a dragon, but highly respected. At least one newspaper reported that Mme Coton had tried her best to extinguish the fire before escaping from the house, getting herself terribly burned in the process.

The newspaper reports are confused and sometimes misleading, but the train of events at Mme Coton’s house that July day in 1858 started sometime before 6 o’clock on that Monday evening. In order to cut her overheads and beat the cut-throat competition from other manufacturers, Mme Coton was employing children (boys and girls) in her manufacturing business, and it was a ten-year-old boy called David Bray, working in the back kitchen, who first raised the alarm when he noticed that the ‘red fire’, which was particularly volatile, had caught fire on his bench. Once he realised the danger, he called out to alert the others in the house, and his brother William (aged 13), who was working upstairs, tried to follow him out of the house, but was badly burned on the staircase, where the fire had spread with alarming speed. The Brays were from Park Street, Kennington Cross, where they lived with their mother Elizabeth. Alfred Dashwood, a painter working for the Gibsons on the day, apparently aided the boys’ escape from the burning house, and coincidentally (or maybe not) both Bray brothers grew up to enter the painting trade themselves, and to have wives and families of their own. Dashwood’s wife Mary, their daughter (Emily, 14, or Alice, 10), and son (Christian, 5), and a little girl called Sarah Ann Vaughan Williams were all part of the crowd in the street and in Gibson’s house in Melina Place at the time of the disaster.

Mme Coton’s stock-in-trade was mainly spectacular commercial fireworks, very much larger and more powerful than the domestic sets we are used to today. It was estimated by George Harrison, one of Mme Coton’s adult employees, that eighty or ninety of her large rockets were in the house at the time. The fire soon caught the more explosive and volatile elements of the house’s contents and there was a first relatively minor explosion at the back of the house, which caused local people to pour out into the street to witness the disaster. The first fire appears to have started before 6pm, with the first explosion about ten minutes later. Some fifteen minutes after that, once three fire engines and some police had arrived, the second much more powerful explosion, or series of explosions, happened, flinging burning rubble at the crowds in the street and at neighbouring properties, causing most of the injuries and damage.

It was the second series of explosions that saw at least one of the rockets shoot into Henry Gibson’s house (1 Melina Place) on the other side of Charles Street, setting fire to it; fortunately Gibson had only a tiny stock of fireworks in the building, and, as a result, his house did not explode. It did, however, suffer major structural damage from the subsequent fire, and its neighbours on Melina Place, Westminster Bridge Road, were severely damaged as well. Gibson later said that he was deafened by the second explosion. It was not until 10 o’clock that evening, following the several explosions, and fierce fires, that the fire brigades got things largely under control.

Apart from the firemen, who worked assiduously and without a thought for their own safety, despite the potential danger of more and larger explosions, one of the many heroes of the hour was the 40-year-old Alfred Dashwood, who was painting the front of Henry Gibson’s premises, on the opposite corner of Charles Street in Melina Place. As soon as he realised what was happening at Coton’s he ran to the building and dragged out three children (presumably William Bray, Jack Watson and Caroline Bridges), all terribly burned. He got them into a cab to be taken to the nearby St Thomas’s Hospital, but then found his own five-year-old son outside on the road, who had been trampled by the fleeing crowds, his collar-bone broken. This son, named Christian after his grandfather, survived the incident and went on to become a plasterer and house-painter himself; he was recorded as living with his widowed mother at Hercules Buildings in the 1881 census.

Other brave souls were a Mr F. Bonham or Banham, livery-stable keeper of 9 Obelisk Yard, who was hit on the back of his head by a huge rocket while he was trying to carry a small girl out of the danger zone, and James Davies, also dangerously burned while trying to rescue other victims. Bonham/Banham’s wife Catherine is stated to be a widow in the 1861 census, so it is possible that her husband eventually died of the injuries he received on that day. Another rescuer, John Secker, carried a ladder to the window of the next door house to aid the escape of a man stuck on the upper floor, but was himself blown off the ladder across the road, where he, too, was trampled by the panicked crowd, although not fatally.

Sad to relate, one of the ladders erected by a rescuer was climbed by a group of men who had been drinking heavily, in the vain hope that they could do something to help; having bravely rescued a chair from the flames, they were all blown into the street by the second explosion, and badly injured; one of the subsequent recorded deaths was that of John Murray, aged 40, one of this group, and a habitual hard-drinker, who suffered a compound fracture to his leg; he died on 27 July at St Thomas’s Hospital. Equally upsetting is the fact that the so-called ‘light-fingered gentry’ were soon active among the crowd, picking the pockets of the rescuers and even stealing the turncock’s tools.

The fire-engines of the parish and of Messrs. Hodges, the local distillers, and some policemen were on the scene even before the second explosion but were unable to calm the confusion and panic; they could only try to keep people away, and flood the buildings with as much water as they could raise from the local water-mains. These mains had been opened for them by Thomas Dunn, the turncock of the Lambeth Waterworks Company, who was himself badly injured, particularly to his head and face when his hat was burned off as he was drawing the plug from the water-main as the second explosion hit him; he was taken to the hospital with little hope of survival. As with several others whose lives had been despaired of, however, the treatment they received from the house-surgeons must have been exemplary, allowing several very serious cases to survive the disaster, if badly scarred. But then again, there is evidence that at least two of the injured died several months after the explosion, and these delayed deaths were never among the ‘official’ statistics of this event.

Thomas Dunn the turncock can be seen with his tools in his hand and being blown backwards, in the centre of the first of two illustrations of the incident in the Illustrated London News of 24 July. [Fig.3] This dramatic engraving shows the scene at the moment of the second and biggest explosion, with flaming debris flying out from Mme Coton’s house, and the whole place on fire. Men, women, children and animals can be seen fleeing the danger to left and right, and past the neighbouring shops (one of which is Mr Herring’s Coach works) on Charles Street in the centre; to the right of centre can be seen a man being blown over on top of a group of children – this was reported to be Mr Phillips, a hat-manufacturer of the Borough Road, blown forward by the concussion of the explosion. To the left of Thomas Dunn is the pony-cart of a scrap and rag-merchant called Lyon Barnard (aged 28) of 5 Gibson Street, with his four passengers being blown to the floor; Mr Barnard was apparently ‘much hurt’ while his passengers were lucky enough to escape unhurt although ‘a good deal shaken’; Lyon Barnard’s death at Guy’s Hospital was recorded on 15 December 1859, just 17 months after the explosion. In the illustration, Barnard’s horse is unsurprisingly taking fright at all the noise and rockets, some of which can be seen to be shooting towards Henry Gibson’s building on the left. To the right of Thomas Dunn can be seen a running woman surrounded by rockets, her long black dress ablaze and her hat flying off. Could this be the fiery epicentre of the disaster, the only likeness we have of Mme Coton herself?

Despite all the heroics and the staunch efforts of the police and firemen, it is said that over three hundred people were injured during this incident, some seriously, others less so. Around 60 people were admitted to hospital, and at least four died. Nine houses suffered serious damage, and the newly erected St Paul’s Church, in common with all the neighbouring houses, had its windows blown out. One of the several miracles of the incident was that Mr Drewell’s firework factory, next door but one to the church, and Mr Sumpter’s building on Charles Street, used as a workshop and store by Mme Coton, both escaped entirely unscathed, as did the local timber-yard. If any of these had been caught up in the disaster, the fire brigades would have been overwhelmed, and the damage would have spread out of control.

There would not normally have been so many people in the street, so it is likely that the number of injuries was made considerably worse by ‘sight-seers’ initially attracted by the commotion but soon panicked into running away again. The Standard newspaper of 14 July reported that, following the first explosion and fire, ‘a crowd gathers and grows denser every minute’. It appears that many of the serious injuries were suffered by passers-by in the street, and by locals endeavouring to preserve lives and property.

In Coton’s premises at the time of the incident were the young Bray brothers, David and William, a 13-year-old boy named Jack Watson, Mme Coton herself, with a servant, Hannah Welsh, an adult employee called George Harrison, and the unnamed little girl – probably Caroline Bridges. It appears that Hannah Welsh, the servant, was the last to escape (with her sleeve on fire), and was able to report to the police that the house was then clear of people. Both Mr Bennett and Edwin Tucker were out on business at the time. Hannah Welsh and George Harrison survived, along with the Bray brothers. William Bray thought that Mme Coton had escaped from the building with him, seemingly without serious injury, but it is clear that at some stage Mme Coton herself was very seriously injured, suggesting that, if she did indeed escape with William, she must have returned to the house, whether to fetch valuables or to rescue somebody is unclear. Because of the horrifying injuries she received during this disaster, the legendary Mme Coton, fireworker to Vauxhall and Cremorne Gardens, died at Guy’s Hospital after a week of excruciating pain; she was just 34 years old. She was cremated and laid to rest at the City of London Cemetery (Square 9, grave 1215). Vauxhall’s fireworks were carried on for the last few weeks of the 1858 season by Signor Duvalli, normally a tight-rope walker, but dragooned into a new role by the proprietors.

It was fortunate for around 60 of the injured that they were taken straight away after the accident to the surgery of Dr Donahoe, almost opposite Mme Coton’s, at no. 3 Westminster Bridge Road. The doctor treated many of the wounded, and, according to The Times on the following day ‘did all that was possible, that humanity or surgical skill could devise’ to help. Without this remarkable doctor in his surgery many more deaths would have been inevitable. His colleagues Mr Bateson on the Waterloo Road and Mr Solly at St George’s Circus treated another handful of cases.

The inquests, which then almost immediately followed loss of life, found that William Bowyer Bennett, as owner of the house where it all started, should answer charges of manslaughter. He was originally convicted on one charge of manslaughter, in the case of Sarah Ann Vaughan Williams, but the following November he was cleared on appeal, on the grounds that he had openly carried on his business for years without any authority trying to stop him; he was acquitted in the case of Caroline Bridges, under a different jury, suggesting that the appropriate laws lacked clarity. He was able to keep up his late wife’s business into the following year, presumably with the help of Edwin Tucker; the final season of Vauxhall Gardens ran for just six days between 18 and 25 July 1859, but the final printed programme announced a ‘Brilliant Display of Fireworks on a surpassing Scale of Magnitude, by Bennet, late Coton’.

After the final closure of Vauxhall the year after the explosion, Bennett was able, probably with some relief, to return to his former occupation as a publican. By the time of the 1861 census, he had remarried (Mary), and was publican at the Jolly Gardeners on Princes Road, Lambeth, later moving on to different pubs in Hayes, Battersea, and Tottenham. At his death aged almost 80, quietly at home in Tottenham, he left effects to the value of £1,475.

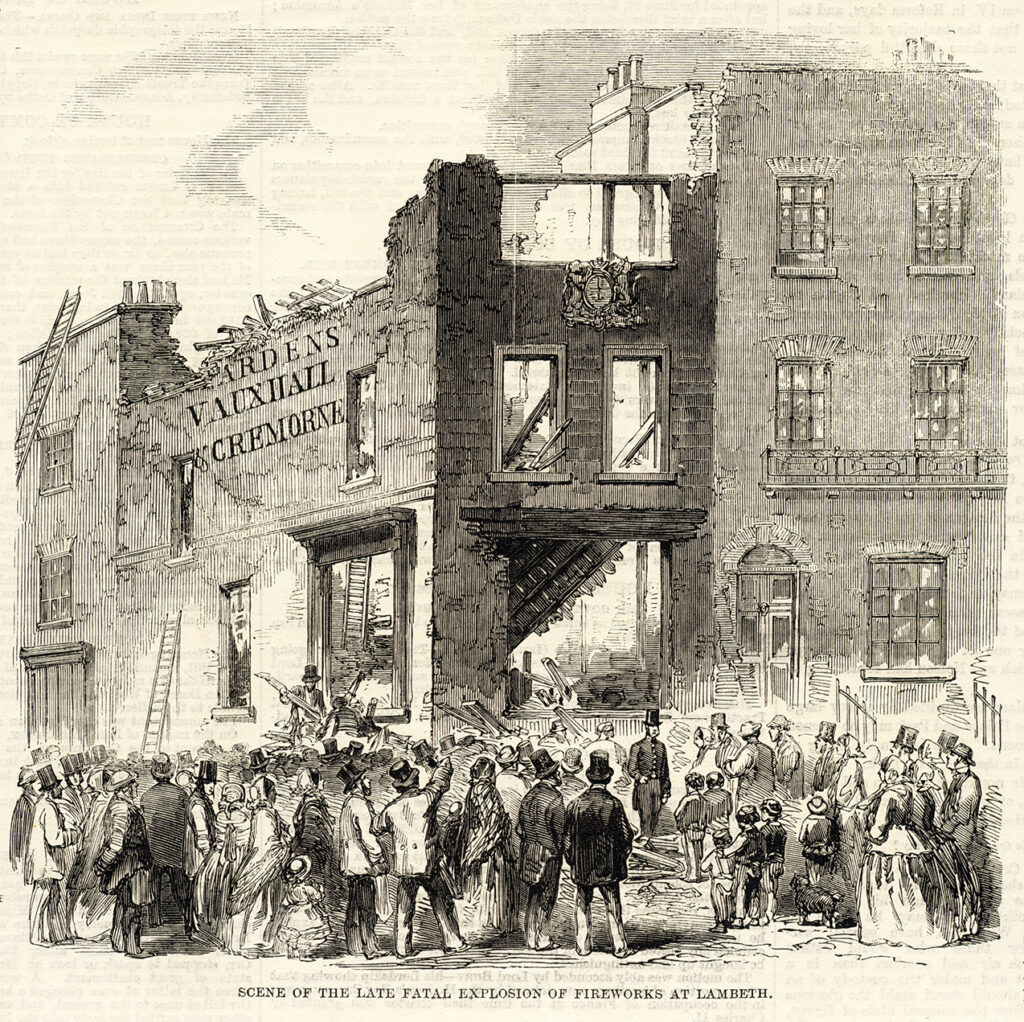

The second engraving in the Illustrated London News of 24 July [Fig.4] shows the immediate aftermath of the explosion. From the obvious scale of the destruction it was clear to the crowds of sight-seers on the Westminster Bridge Road that Mme Coton’s building would need total demolition, if only to make it safe. The Royal Warrant coat of arms and plaque can be seen still clinging to its place below the second floor windows on the Westminster Bridge Road façade of the building. Below it, a police constable can be seen trying to keep people away from the ruin, but faced with such a crowd on his own, he is having limited success, despite the fact that the danger of falling masonry and other debris is by no means over.

Although no houses from the period survive on the site today, all the damaged houses must eventually have been repaired, but was Mme Coton’s re-built from the ground up? The site in 2023 is free of housing, and supports only a row of five free-standing garages next to a playground, so it is possible that the house was never rebuilt. Demolition of the ruins of Coton’s house started on the Thursday after the explosion, undertaken by John Ramsey the landlord. Ramsey was ordered to take down before mid-August all four badly damaged buildings in Elizabeth Place and Charles Street in his ownership. The landlord of Gibson’s was a Mr Cole, who had the same responsibility for his properties in Melina Place. This site too appears to be vacant in 2023, backing onto a late Victorian school building (more recently a business centre), which looks as though it could well have been built soon after the explosion.

The strength of feeling at the ratepayers’ meeting reflected the fact of the many severe injuries, the several deaths, and the widespread damage to property caused by the incident – at least nine buildings including the two firework factories and their neighbours had been seriously damaged. The first death was that of Sarah Ann Vaughan Williams just 11 years old, the only recorded fatality on the day of the incident. Sarah’s father Edwin, a portrait painter and teacher of astronomy from Bridgnorth, had just moved with his wife Mary and their family into rooms nearby; Sarah had been sent out to post some letters, so she was not on the spot at the time of the first blast; however, she soon returned and, thinking herself safe on the other side of the street, called in to meet Mrs Gibson and the Dashwood family not long before Gibson’s house too was engulfed by fire after one of Mme Coton’s rockets had flown through a broken window, hastening their need to escape; according to the testimony of Mr Dunn (reported in the Lloyds Weekly Newspaper of the 18 July), ‘in endeavouring to escape, [Mrs Gibson] was caught by the sulphurous flames, which rose high over her head, and such was the suffocating nature of the smoke that she was unable to move until pulled bodily away by those standing near, and even then she was crying out for the poor girl [Sarah Williams] who perished in the ruins.’ Her visitors Mrs Dashwood and her daughter escaped before her; whether she was overcome by smoke or hit by falling debris, Sarah Williams never left the house alive, and her cremated remains were discovered the next afternoon by ‘Bob’ the fire-dog belonging to Mr Henderson, chief officer of the D section of the fire brigade. It was reported that Sarah’s elder brother Valentine, who would have been about 17 at the time, identified her body, but this must have been an appallingly distressing thing for him to have to do in the circumstances.

Caroline Bridges, the daughter of John, a wheel-wright or ‘wheeler’ (misleadingly called a ‘whaler’ in one report), was seen by a police constable, George Pike, standing between the two houses, just before she was blown right across the road by the second explosion at Coton’s; the constable ran to pick her up and found that her clothing was on fire, so he doused her with water, and had her sent to the hospital where she was found to have serious burns around her face, hands, back and neck. She became delirious and died at midday on the Wednesday. Her younger sister, Mary Ann, was also badly injured on her feet and legs during the incident – it is likely that she was the ill-fated little girl who was seen trying to run away towards the river, but was overtaken by a rocket that set light to her dress, following which she was knocked down by a horse and her legs were run over by the wheels of the cab taking some of the other casualties to hospital. On the Saturday after the incident, their poor mother, also called Caroline, had to apply to the Lambeth Police Court for help from the poor-box to enable her to have her daughter Caroline decently buried. She said that the burial could have waited until they were able to raise the funds from their friends and family, but the body was so badly burned that decomposition overtook the time available; burial had become urgent, and she had her other injured daughter to care for as well. She was given ten shillings. Members of the public were touched by her story and made such small contributions to her as they could. It is also known that local tradesmen in the parish got together to raise a fund for Henry and Elizabeth Gibson, who lost everything in the fire, and were, like Mme Coton, uninsured. Elizabeth Gibson’s injuries were so severe that she was kept in at St Thomas’s Hospital for 11 weeks.

The article in the Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper already quoted above goes on acerbically:

Reform must be purchased by sacrifices; and twenty maimed babes of the gutter could not count against the singed eyebrow of a young viscount! It is sad to arrive at the conclusion that this long neglect on the part of the legislature of the dangers of the Westminster-road is the consequence of the plebeian character of the neighbourhood.

Had Mme Coton’s factory, the writer asks, been within rocket-shot of a royal or noble house, would she ever have been allowed to carry on her trade there ‘at the risk of obliging her Majesty or Lord Lansdowne with an occasional explosion?’ Obviously not. More importantly, on Friday 16 July, just four days after the explosion, the ratepayers of St George-the-Martyr, Southwark, convened a meeting at the girls’ school-room, St Paul’s school, opposite the site, to urge the government to bring in measures to prevent the manufacture of dangerous and explosive products ever again taking place in residential areas. The outcome of the meeting was that a petition should be sent to the Home Secretary, Spencer Horatio Walpole, asking that ‘very stringent measures may be adopted by Government to prevent not only the sale but the manufacture of such dangerous commodities in the vicinity of public roads and inhabited houses.’ [Fig.5] The Coroner, Mr Serjeant Payne, when judging the case of some of the subsequent deaths, pointed out that, under the statute of William III, 9th and 10th, c.7, it was enacted that no fireworks of any description were to be made by anyone, except by the Government, for Government purposes. This law was still current in 1858 and had been backed up by the Metropolitan Building Act, 7 & 8 Victoria, 84, so it should have been enough to prevent the manufacture anywhere, let alone in residential areas.

This legal history led Walpole to conclude that the law was already sufficient to put a stop to the manufacture and sale of fireworks in residential areas, if only it were properly enforced by the parish authorities. He was quite right in asserting that the current laws would criminalise new firework factories being set up, but they did nothing to close down existing ones. Bit by bit, however, as the old factories closed, and new ones were disallowed, the danger of fireworks factories in urban streets would disappear. Several reports after Mme Coton’s disaster refer to the vain efforts of Southwark’s parish Inspector of Nuisances, a Mr Wellman, to entrap local shopkeepers into selling fireworks so they could be sued; but the laws were poorly drafted and confusing, therefore ineffective. Government inertia meant that the protection of the public from such dangers took a long time to come into effect. It was not until 17 years later that the Home Office finally took the first tentative step of instituting annual inspections of explosives factories under the Explosives Act 1875 (38 Victoria.c.17).

So, despite all the news reports and petitions to government, the four deaths directly resulting from that day’s incident actually had very little immediate effect on the existence of firework factories in towns and cities around Britain. By the time of another, even more lethal, explosion at Mr Fenwick’s firework factory on Broad Street Lambeth, on Tuesday 4 November 1873, during which eight people, including four more young children, were killed, all the Illustrated London News (15 November 1873) could say rather feebly was, ‘The law prohibiting this dangerous manufacture in common dwelling houses should be more strictly enforced.’ However, over the years these dangerous factories and warehouses were banished to isolated places, and it must be hoped that the tragic deaths of those two little girls had some influence on this outcome. Mme Coton knew very well that she was putting her life in danger every day, and John Murray was so drunk that any inhibition he may have felt about approaching a burning firework factory were quickly overcome, but Sarah Williams and Caroline Bridges were the classic innocent bystanders, fatally caught up in the ‘flaming whirlwind’ that wreaked such havoc in an ordinary London street on that July evening in 1858.

—–

Of the 300 or so injuries received on that day, most were minor and could be treated at home – first degree burns, abrasions, bruises and the like; around 70 were treated by local doctors, especially Dr Donahoe, but also Mr Bateson on the Waterloo Road and Mr Solly on Blackfriars Road. It is not known whether any of these patients went on to develop more serious conditions, or, indeed, died from their injuries. There are four ‘official’ fatalities – Sarah Ann Vaughan Williams (on 12 July), Caroline Bridges (on 14 July), Mme Coton herself (on 20 July), and John Murray (on 27 July) – for each of whom inquests were held.

Around 40 people are known to have received serious or life-changing injuries and/or third-degree burns, and to have been treated at St Thomas’s or Guy’s Hospital. Several were lucky to survive at all:

Lyon Barnard, rag and scrap merchant (‘injuries to his legs’)

Frances Ellen Bennett / Mme Coton (fatality)

John Bennett (13) (‘burnt arms and face’)

Mr. F. Bonham, Livery-stable keeper (‘his case is pronounced to be one of extreme danger’)

David Bray (10)

William Bray (12/13) (‘fearfully injured’)

Caroline Bridges (11) (fatality)

Mary Anne Bridges (9), Caroline’s sister (‘fearfully burnt about the lower part of her abdomen’)

Joseph or James Brooks (13) (‘run over and seriously injured’ ‘Severe contusion of face’)

Charles Cherwood (23) (’burnt’)

Emily Clark (16) (‘so much injured that not a feature of her face is recognisable’)

Charles Coble (22) (‘burnt in the head’)

George Cooper (‘doubts are entertained of his ever recovering . . . both his eyes have been destroyed… the lens of his eye being torn out’)

Richard Corner (69) (‘knocked down and run over’)

J. Crampton (or Crumpton or Frampton) (4) (‘frightfully burned about the lower extremities’)

Lydia Crampton (39) (‘burnt in the back’)

Christian Dashwood (4 or 5) (‘a broken collar-bone’)

James Davies, boot maker (‘dangerously burned’)

John Davies, nephew of the bootmaker James Davies (‘blown a considerable distance into the air, and, in falling, he dropped upon the water gushing from the plug, which again lifted him two or three feet from the ground, but fortunately the force of water discharged was the means of saving his life’)

Emma Delaney (14)

George Delaney (9) (‘probably blinded’)

Thomas Dunn (the turncock) (‘burned around the face and head, causing it to swell to double its size’)

Elizabeth Gibson (‘so severely burnt about the back and thighs as to render her case most dangerous’)

T. Gibson (48)

George Glew (26) (‘very much burnt’)

Mr William Harris, publican, the Equestrian Tavern

Edward Hart (16) (‘very fearfully burned face and arms’)

Master Johnson (‘received a tremendous wound on his head, and blood flowed from his mouth’)

Mr Lock, possibly Police Constable 80L (see below) (‘knocked down and trodden upon’)

Mr Mannering

John D. Murray (40) (fatality)

Mr Paget, a confectioner, and his daughter

Mr Patterson, publican

Mr Phillips, hat maker (’blown over by the concussion’)

Police Constable 80L (‘blown under a horse and cart, the horse treading on his knee’)

Master Rawlins (‘seen near the explosion but missing’)

Richard Sampson (16) (‘very much burnt – serious case’)

John Secker (‘much hurt about the arms and chest by being trodden upon’)

Mrs Smith (‘much injured’ with Miss Vokes)

Miss Vokes (‘struck by a shower of rockets’)

Mr Wallace

Mr White, landlord of the Crown tavern (‘knocked down’)

Sarah Ann Vaughan Williams (11) (fatality – ‘burned almost to a cinder’)

Most of the information in this article is drawn from contemporary newspapers – The Times, The Daily Telegraph, The Morning Chronicle, and Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper in particular, but many others repeated the stories, often with their own additions and amendments. Some of the articles were published in the four or five days following the disaster, but others follow the later inquests and trials and other consequences. Several of the articles confuse or misreport names and ages. All the main information about the protagonists has, as far as possible, been checked through genealogical and other sources by Karen Coke.