Arles, Auckland, Baltimore, Barbados, Brussels, Canterbury (NZ) Charleston, Nashville, New York, Melbourne, Pavlovsk, Philadelphia, Stockholm, Toronto, are some of the places that at one time had ‘Vauxhall Gardens’. David E. Coke, historian of Vauxhall’s original and much-imitated Royal Vauxhall Gardens open-air pleasure resort, tells their story and wonders in what part of the world may languish the remains of Vauxhall’s original ‘Gothic Orchestra’ bandstand.

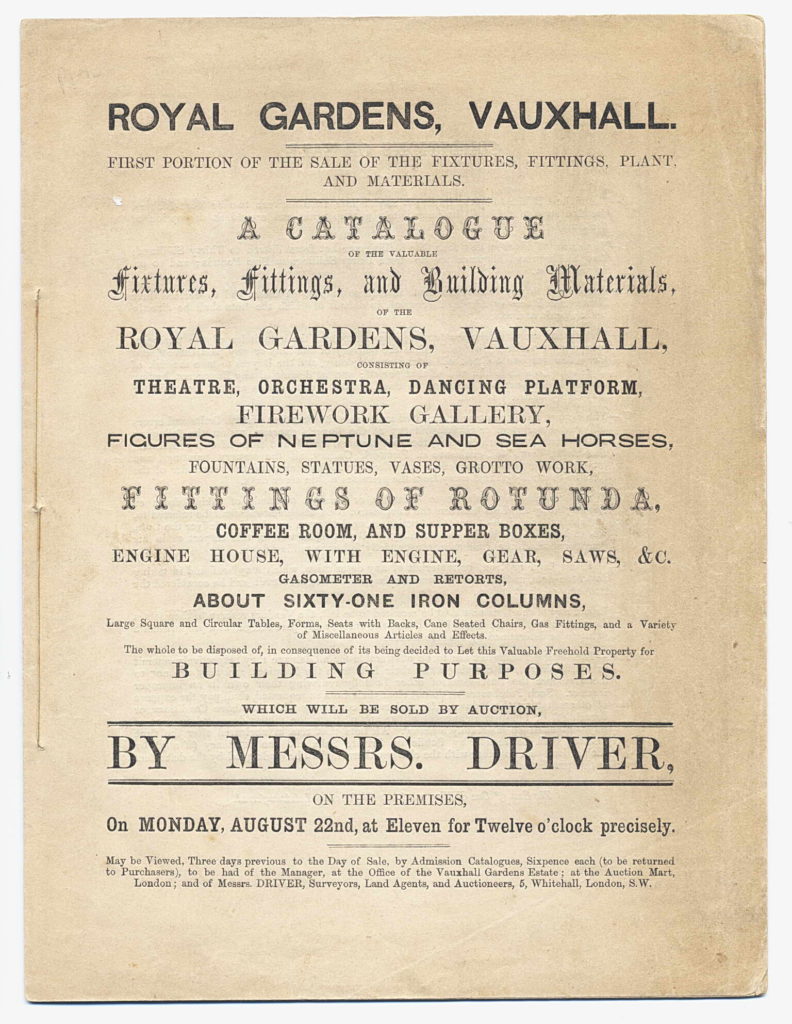

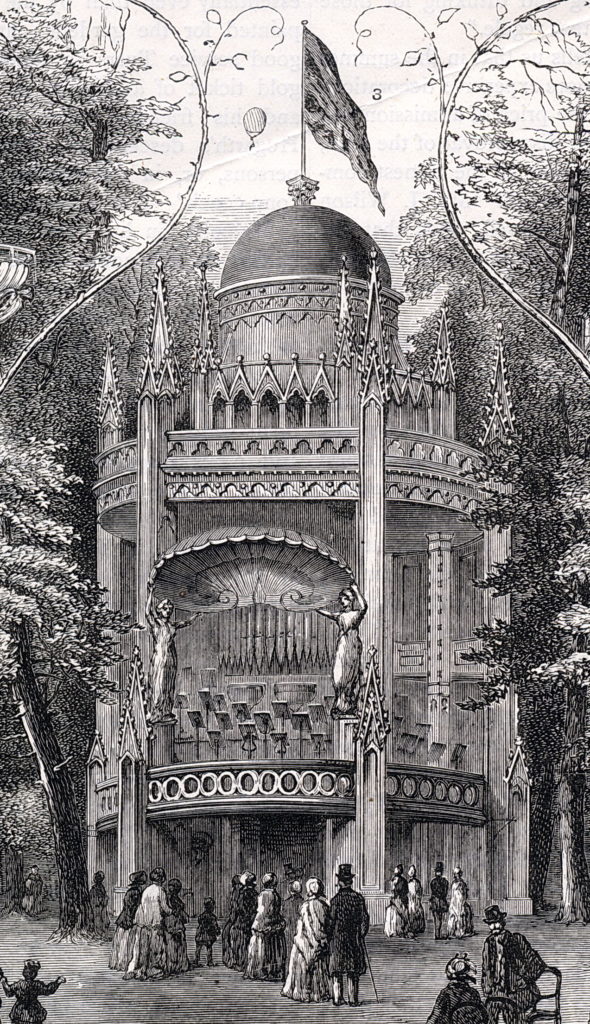

At their disposal sale of the ‘Fixtures, Fittings, and Building Materials of the Royal Gardens, Vauxhall’, on 22 August 1859, the auctioneers, Messrs. Samuel and Robert C. Driver of Whitehall, sold as lot 125 (Fig.1):

The entire erection of the elegant Circular Orchestra with minarets, leaded cupola roof, and gallery, American, Stout and Oyster Bars, with the fittings, shelves, and 2 beer engines and pipes, metal top counter, stairs frontispiece, and pipes, and machinery of organ, bellows, & 2 figures on pedestals, supporting shell sounding-board, 4 looking-glass panels, &c., &c.

At the auction, which took place at the gardens, the Orchestra building fetched £99, but no record was kept of the purchaser. Its current whereabouts are unknown.

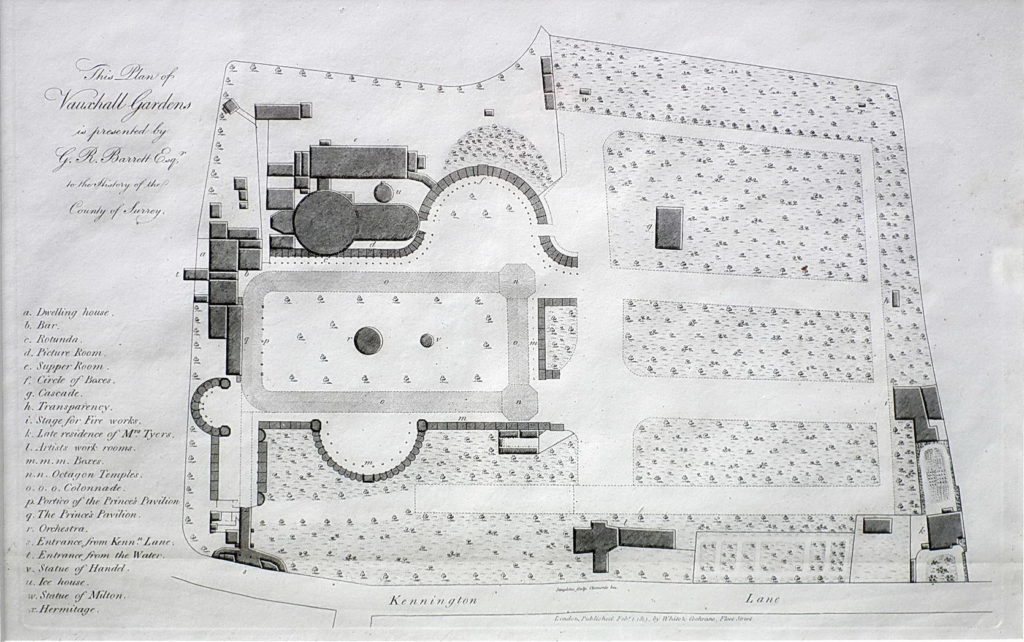

The ‘Orchestra’ or bandstand had stood on that spot, in the centre of the Grove at Vauxhall Gardens, by 1859 ‘Royal Gardens, Vauxhall’, for more than a century, since 1754. (Fig.2)

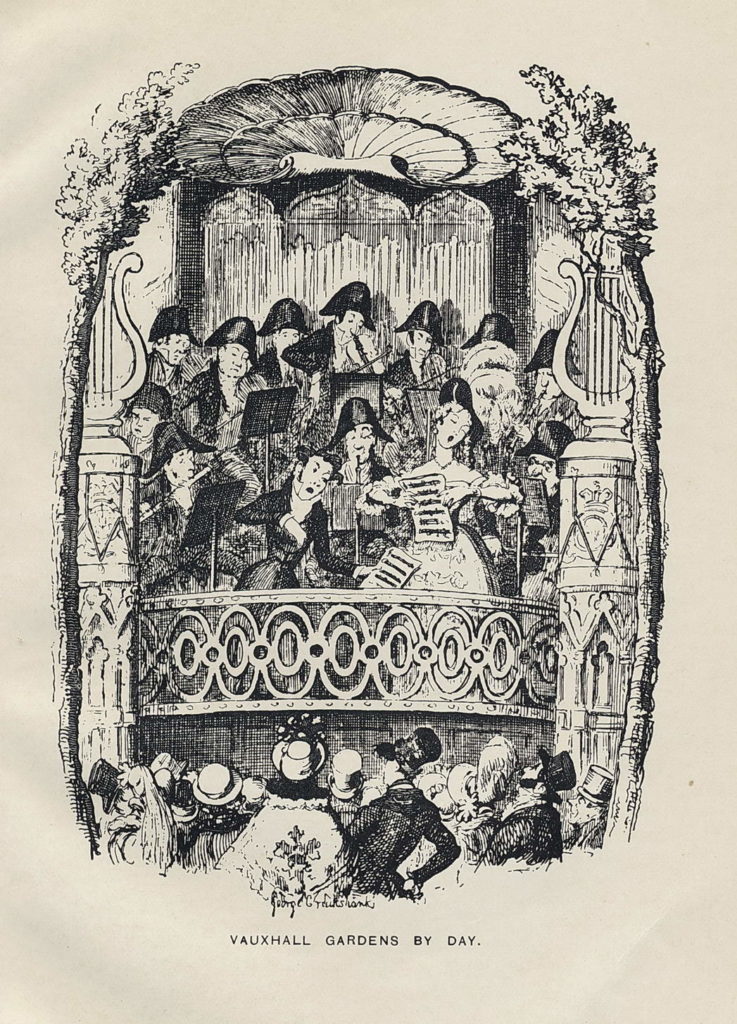

During that time it had undergone several major alterations and many refurbishments, but, basically it was the same structure that Jonathan Tyers himself had commissioned to replace his original rather uninteresting outdoor Orchestra-stand. The new building would have been known by all the great Vauxhall musicians from Handel onwards. (Fig.3)

The various bars that Mr. Driver tells us are housed in the ground floor of the Gothic building were recent makeshift additions to the noble old building, as was the Ice Cream bar which is visible in the extraordinary photograph taken in 1859 and preserved in the Lambeth Archives. More worthy additions were the great ‘shell’ sounding-board, added in 1824 by the Gardens’ carpenter Thomas Lowe, and supported on two huge decorative lyres set on top of sculpted drums.

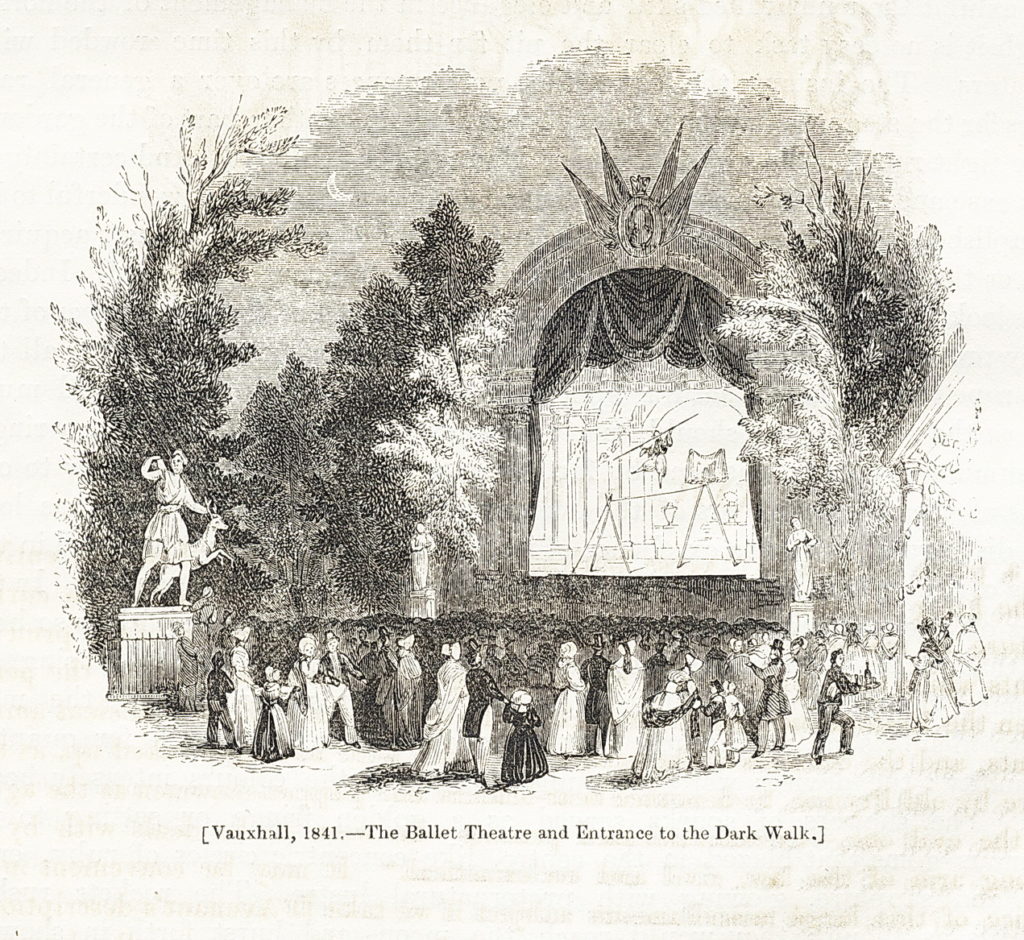

That year the Orchestra was re-painted in pink, white and gold. The lyres and drums were later (1845) replaced with draped female figures or caryatids on pedestals to support the shell, during the overhaul and redecoration of the building carried out by the chief painter and decorator, Mr Hurwitz, “in the most costly taste.” (Fig.4)

If nothing else survives of the Orchestra, these two supporting figures may do so; it was suggested that they might have been re-used in the old portico of the Tate South Lambeth Library (long ago removed), which had its own pairs of caryatids supporting the small roof, but those figures, according to contemporary prints, were rather different.

The great shell sounding board can be seen lying on the ground in a watercolour by James Findlay in the Museum of London, painted on the spot while the building was being demolished for removal in November 1859. It is obvious from this and other late views of the Orchestra that the building was in less than pristine condition, extensively oil-stained and scorched from the illuminations, and that it would have needed considerable restoration to be re-erected somewhere else. But presumably, the fact that somebody paid almost £100 for it suggests that it was destined for a new use, rather than merely scrap or firewood (£100 to a skilled tradesman or a household servant would have been two years’ wages, or would have bought six horses, 18 cows, or 151 stones of wool). The organ would have been worth something, even after a century of hard use, the lead from the cupola would have had some scrap value too, and even the bar-room equipment may have been worth preserving, but £99 would have bought all of that as new, and more besides, so it is probable that the building was intended for a life of its own after Vauxhall closed.

Maybe it was re-used at another pleasure garden, either in this country or overseas. There were so-called ‘Vauxhalls’ all over the world, mostly short-lived and mostly fairly disreputable, but there may have been one or two with higher aspirations, even one that was started up by a member of Vauxhall’s own staff, finding himself out of work. Some staff members are known to have emigrated to the USA and to Australia. Most of the UK Vauxhalls had closed by 1859, so it may be more fruitful to look further afield; the USA had many Vauxhalls, in Charleston, Nashville, Baltimore and Philadelphia, but especially in New York where a pleasure garden called the Palace Gardens was developed from 1858, very much inspired by the earlier pleasure gardens; Palace Gardens were built on an open lot between Fourteenth and Fifteenth Streets, New York, by Cornelius V. Deforest and his partner called Tisdale. Here they even erected ‘a large, two-level octagonal orchestra, a fireworks platform and several arbours.’ This Orchestra is shown in an 1858 print of the gardens, and it is probably not the Vauxhall orchestra, although not so different either, suggesting that, even though the Vauxhall Gardens Orchestra was over a century old, its shape and size would still have been acceptable to a later 19th-century audience.

In Australia and New Zealand, Vauxhalls, Cremornes and Ranelaghs came and went with surprising rapidity through the 19th century – Adelaide, Kalgoorlie, Perth, and, of course, Sydney and Melbourne all have well-recorded pleasure gardens. The best known of the Antipodean gardens was the ‘Vauxhall’ at Dunedin in the South Island of New Zealand, founded by Henry Farley in 1862. A Mr C. Farley had directed the re-enactments of the Battle of Waterloo at London’s Vauxhall in the 1820s and ’30s – maybe Henry was a relative.

One of the best set-up pleasure gardens in Australia was Cremorne Gardens (named for the successful gardens in Chelsea) in the Melbourne suburb of Richmond, founded in 1856; here £60,000 was invested by George S. Coppin in his new venture. Coppin was consciously trying to emulate London’s Vauxhall, and his nostalgic entertainments included ‘Golden Age’ fireworks, with balloon ascents, music and dancing; he even emulated Vauxhall’s great illuminated dioramas, showing the “Siege of Sebastopol” with artillery and fireworks in 1856. Might he have wanted to re-erect the old Orchestra at his new pleasure garden? He certainly had the capital to do so.

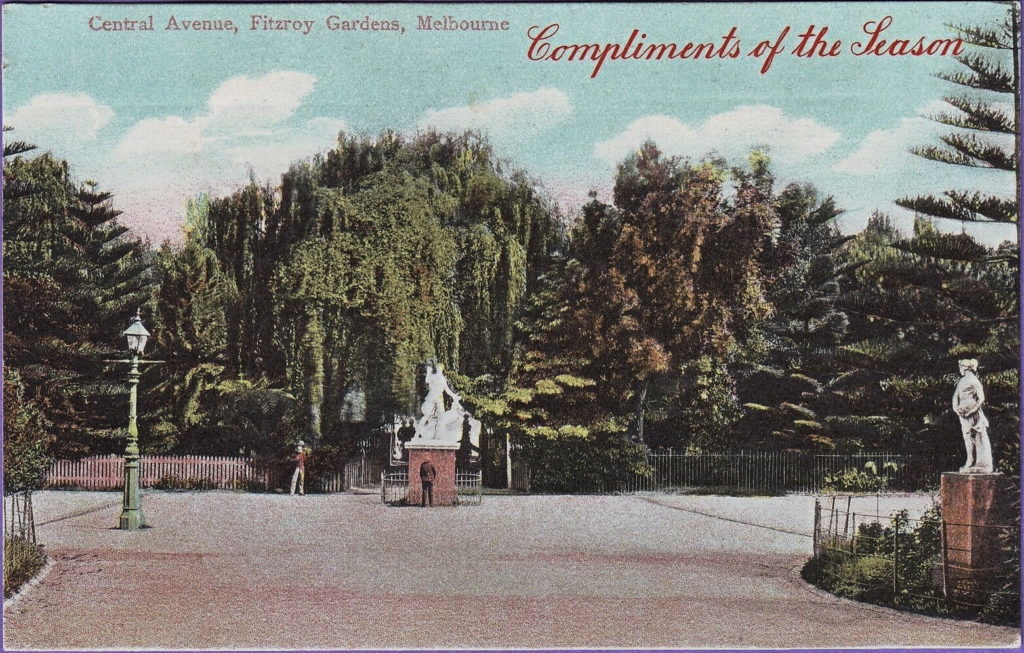

Melbourne is absolutely the kind of city where Vauxhall’s old Orchestra could so easily have reappeared; it is probable that other features of Vauxhall Gardens had already found their way there in the 1860s; the numerous statues displayed from before 1864 until the 1930s in Melbourne’s Fitzroy Gardens, some of which look very like statues known to have been installed at Vauxhall in the 1820s, were sold at the same sale (lots 129–134) as the Vauxhall Orchestra – did the buyer take them out to Melbourne, and did the same buyer also acquire the Orchestra, dismantle it and pack it up, and then transport it 10,500 miles to a new home and a new life? Having paid the equivalent of five hundred days skilled wages for the old building, maybe he did. It would surely have been a worthwhile investment as a good selling-point for his new business. There was widespread ‘homesickness’ among emigrants who found themselves cut off from English culture and English history, so any link with ‘home’ would have been treasured and much visited. Many emigrants would have known Vauxhall before leaving England, and reports of events at Vauxhall were carried in the Australian and New Zealand press until its closure, so everybody would have heard of it even if they did not know of it personally. Australia still has an outstanding array of fine park bandstands, largely built between the 1870s and 1920s and beautifully maintained today, which are the direct descendants of Vauxhall’s Orchestra, helping new immigrants to feel at home. (Fig.5.)

Both the Vauxhall and Fitzroy Gardens statues were cast from artificial stone, painted white; such objects would not have been easily available in Melbourne at the time, so were worth the considerable cost and difficulty of transporting them from London. Most of the statues were unremarkable classical standing figures, usually female, emblematic of the seasons or of mythological characters. The one distinctive piece portrays ‘Diana arresting the Flying Hart.’ This same subject had been installed, the same size and precisely the same model, at Vauxhall, and appears in an engraving of the Ballet Theatre in the 1840s. (Fig. 6)

Whether the two were identical or not is still open to conjecture, but there appears to be no compelling evidence against the possibility. The eventual disposal of the Fitzroy statues may have been brought about by the difficulty and expense of maintenance, once the artificial stone began to break down, more than a century after their manufacture. (Fig. 7)

If the Orchestra did not find its way to Melbourne with the statues, there are at least two other possible Antipodean stopping-points, whether at Kohler’s Vauxhall in Canterbury, New Zealand, launched in 1860, or William Colby’s Vauxhall Gardens in Auckland a few years later. Both are poorly recorded in the visual documentation, so it is not obvious what sort of architecture they included.

Taverns, parks and suburbs named Vauxhall are found world-wide; these are sometimes all that remains of a public garden or concert-room; Marseille and Arles in the south of France both have Vauxhalls; places as diverse as Barbados, Brussels, Toronto, Stockholm and Pavlovsk too. These would appear to be unlikely candidates for acquiring the Vauxhall Orchestra, particularly when the start-dates for the Australian and New Zealand gardens coincide so closely with the end-date of Vauxhall itself, and others do not. On the other hand, there is no accounting for the eccentricity of that one Vauxhall aficionado who became so obsessed with the gardens that he wanted to keep the iconic Orchestra building himself for no obvious reason other than sentimental attachment. One such might be John Fillinham, one of the great collectors of Vauxhall memorabilia, who with his friends Theodosius Purland and F.W. Fairholt attended the ‘last night forever’ and heard the tenor Russell Grover sing ‘Nevermore’ to close the evening.

The Orchestra may still be languishing, in pieces, in a warehouse just yards from its original site, or it may have been taken to the other side of the world, or else it may not have survived at all. If this is the case, though, was any relic preserved ? – the old organ’s keyboard, the caryatids, the shell-shaped sounding board, a gothic pinnacle from the roof, or just a music-stand, all visible in the illustration, are all possible survivals.

If you know of anything that could be the Vauxhall bandstand, David E. Coke would love to hear from you through the contact page on his website www.vauxhallgardens.com.

© David Coke, 1 July 2019

All images are from originals in the author’s collection, and copyright to the collection © CVRC, 30 June 2019.