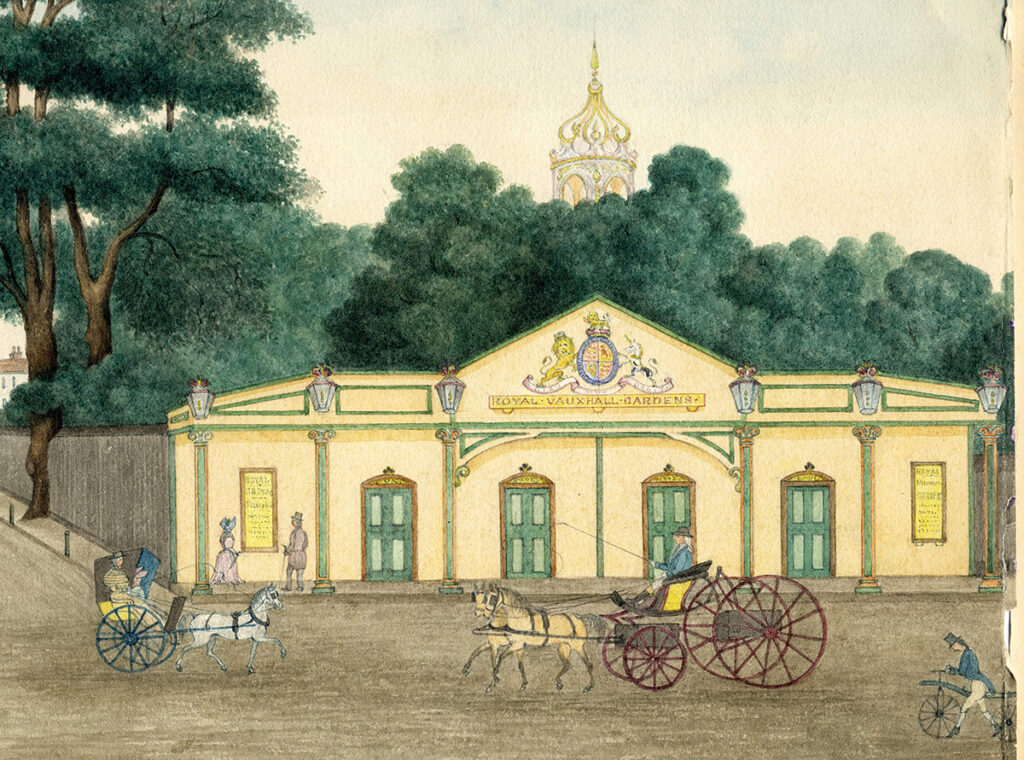

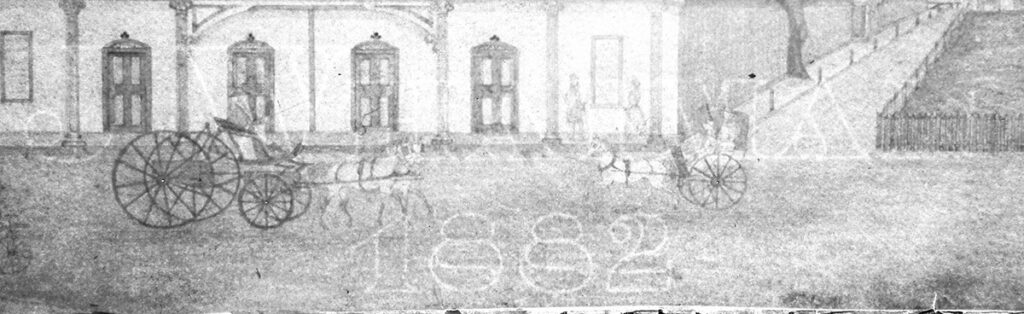

The recent discovery of an anonymous 19th-century watercolour painting of ‘The Coach Entrance, Royal Gardens, Vauxhall’ has sparked a series of questions about its purport, its authenticity and its odd topography. Vauxhall History co-editor and co-author of Vauxhall Gardens: A History David Coke suggests an intriguing answer to these questions.

This watercolour painting of the so-called Coach Entrance (or Kennington Lane Entrance) to Vauxhall Gardens surfaced in a private collection in the United States. The owner, who inherited the collection from her mother, offered the painting for sale on a well-known online auction site. It is now back in the UK and is the subject of ongoing research; this essay is the first result.

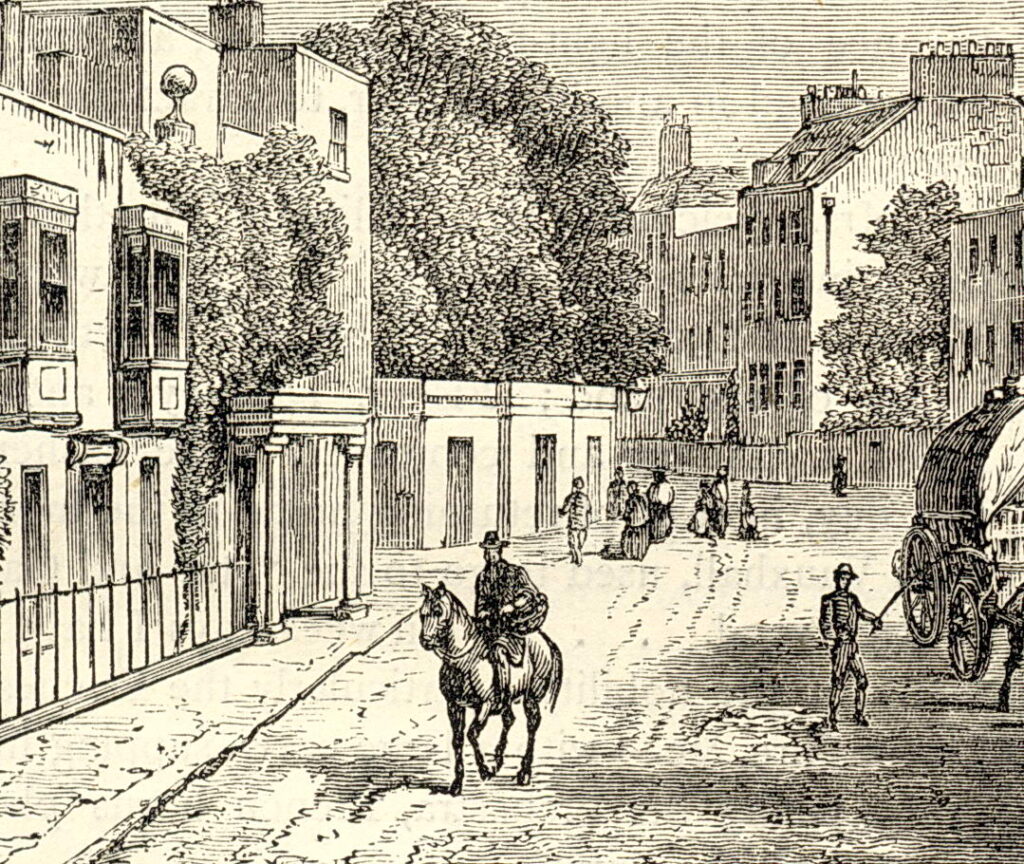

Vauxhall Gardens’ Coach Entrance was situated at the south-west corner of the gardens, overlooking Kennington Lane (in the foreground of this picture), roughly on the spot where the Royal Vauxhall Tavern stands today. It would have been a famous local landmark, even to people who had never visited the Gardens. It was built around 1830, replacing a simpler earlier structure[Fig.2], and was demolished with the rest of the gardens in 1859.

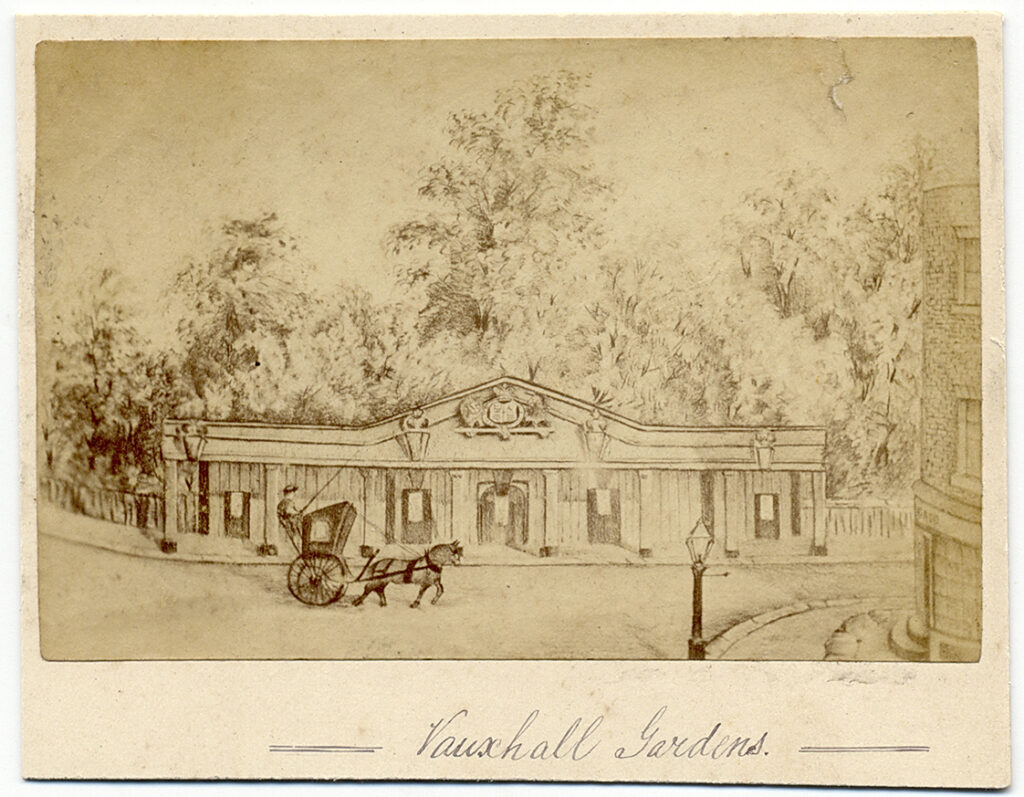

It is known from a group of 1850s watercolours that the Coach Entrance of the final decades of Vauxhall’s life was a small and relatively simple building [Fig.3]. It was little more than a frontage with a covered colonnade to shelter pedestrians and a central pediment bearing the Royal coat-of-arms; there were kiosks behind the façade for the door-keepers, with a covered way leading into the Gardens; like many of its fellows at Vauxhall, the building was made entirely of timber. Its purpose, as the name suggests, was to provide a convenient entrance to the Gardens for visitors who arrived by coach. They could be dropped off at this entrance and pay their admission fee without having to walk the fifty metres or so to the main entrance through the Proprietor’s House. Their vehicles would then be driven to the adjacent grassed coach park, where the horses were watered and rested before the journey home later the same evening or early the following morning. Coachmen were able to take advantage of the many local public houses, including the popular Vauxhall Tap, the Royal Oak, the George & Dragon, the Vine, Marble Hall, the Pilgrim, the Black Prince, and several other smaller inns.

Four main doorways punctuated the façade of the Coach Entrance, and the covered portico was supported on eight columns. The parapet had a number of crowned lanterns fixed to it; the boundary fence enclosing this corner of the gardens curved away to the left of the Coach Entrance, running as far as the Proprietor’s House. Behind the fence were many mature trees, through which Vauxhall’s Orchestra building could sometimes be discerned, but only in winter when the trees were bare.

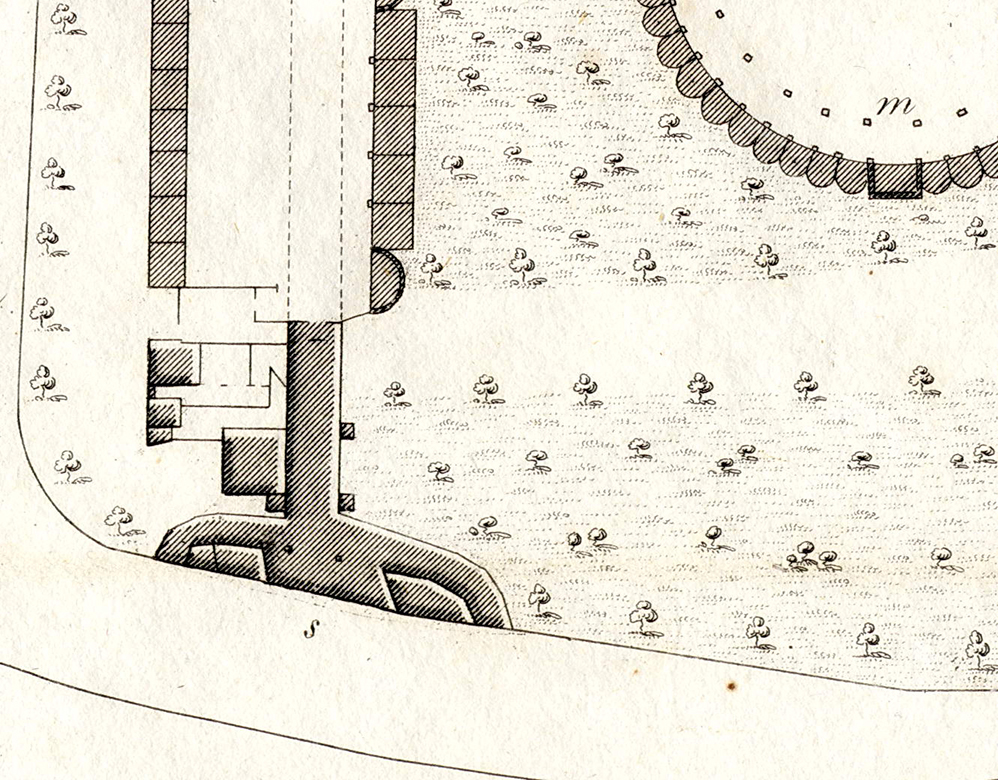

The new watercolour agrees with this topography in general, but not in its details. It shows the building as it never quite was. The basic geography is fine, but the boundary at the south-west corner of the gardens (to the left of the Coach Entrance building) was never a right-angle, always a curve, as the Royal Vauxhall Tavern’s façade still is [Figs. 4 & 5]. Neither does the architectural detail of the yellow Coach Entrance in this new watercolour agree with any of the previously-known images, especially in its parapet design, which is more elaborate than it should be, with green panels and tapered ends [Fig.6]. Most of the other images also show four doorways, but with a larger central opening, usually closed, making five in all, without the flanking advertising noticeboards. They invariably include eight columns supporting the portico, rather than the six seen here.

The white house immediately to the left of the large tree has to be the Proprietor’s (or Spring Gardens) House, but it is too small and the wrong shape. The entrance gate in front of it is in the wrong place; the corner of the Coach Field should be canted, cutting off the corner so as to make a wider splay for coaches coming out of what is now Goding Street onto Kennington Lane towards the new Vauxhall Bridge away to the left; although it may well be historically correct, the little grey ‘sentry-box’ on the extreme left of the image does not appear on any plan or in any other known image, and the Vauxhall Tap should only have three windows on the first floor, not five [see Lambeth Borough Photos]. The final anomaly is the prominent Gothic turret behind the trees immediately beyond the central pediment of the yellow building. This might be thought to be the pinnacle of Vauxhall’s outdoor Orchestra-stand, but it could not be – the Orchestra is well recorded in the visual documentation at all periods and it never had a turret like this on top; in any case, from this viewpoint, even the highest point of the Orchestra would be completely obscured by the trees when they were in leaf.

For an amateur topographical watercolour, these anomalies might be explained by artist’s licence, by the artist misinterpreting original sketches, or by alterations and additions to Vauxhall’s stock of buildings, land and attractions. An alternative explanation could be that the artist was presenting a view of what might have been – specifically a design for a new proposed building on this site. Without additional evidence, and because of the highly defined detail of the picture, this would have been the most logical interpretation of the new watercolour.

However, closer inspection of the paper on which it is painted reveals the most important clue in this puzzle; held up to the light, it can be seen that the paper has a manufacturer’s watermark – ‘J. WHATMAN 1882’ [Fig.7]. This watermark dates the picture to more than two decades after Vauxhall Gardens had closed, so it could not be a design, and must have had a very different starting-point. There is nothing about the present physical state of the watercolour to suggest that it is anything other than a genuine work from the 19th century, so an intentional later forgery can be ruled out. But the artist clearly did not paint this scene from life, and must have invented it to look like something from fifty years earlier, based on a little bit of historical research.

An obvious feature of this picture is the trio of vehicles seen on Kennington Lane. The side-by-side two-wheeled Hackney or ‘Coffin Cab’ at the left end of the building is of a type developed in the 1820s and illustrated by George Cruikshank in Dickens’s Sketches by Boz of the 1830s; the two-horse Perch Phaeton in the centre is a typical high-status vehicle of the same period, and, on the right, the walk-along velocipede, although still around, would have been a little old-fashioned by 1830. The costume worn by the men and women who populate this scene all back up the other details to suggest a date for the imagined scene in the 1830s, but painted half a century later.

In view of this determined retrospection, it may just have been the work of a local painter catering to the nostalgia that certainly existed for Vauxhall Gardens at the end of the 19th century but, if so, it would surely have shown the inside of the Gardens, not just the utilitarian Coach Entrance. However, this very real nostalgia had several important results: it was during this late Victorian period that some of the great collections of surviving Vauxhall ephemera, now in major museums and libraries, were created. Warwick Wroth’s seminal book The London Pleasure Gardens of the 18th Century, based on his own collection (now in the Museum of London) was published in 1896, as was H.A. Rogers’s Views of Some of the Most Celebrated By-gone Pleasure Gardens of London. The important collections of Robert Gould Shaw (Harvard Library Theatre Collection), of James Winston (Bodleian Library, Oxford), of Jacob Henry Burn and of Henry Evanion (both in the British Library), of Wroth himself, of F.W. Fairholt (Theatre Museum, London) and of other avid collectors all stem from this period, when the regret for the irrevocable loss of Vauxhall Gardens, and all that it represented, was at its most insistent.

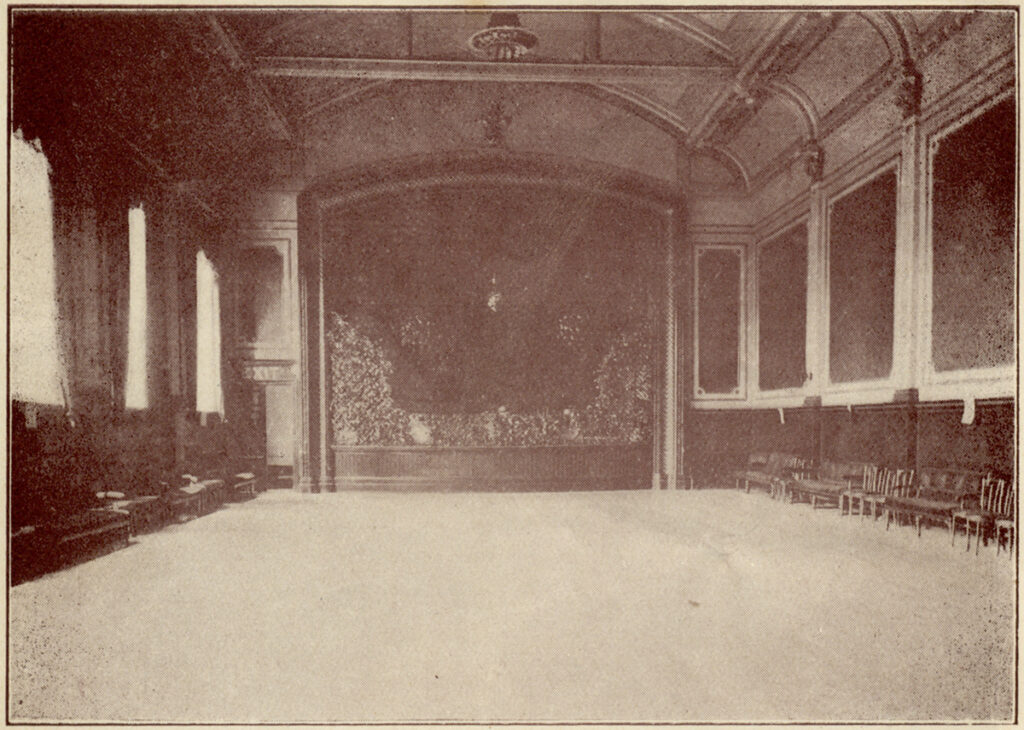

In addition, there was one significant occasion at this time that might have prompted the creation of works like this new watercolour. This was the ‘Vauxhall Revival and Bazaar’ held in June 1888 at the Assembly Room of William Buxton’s recently rebuilt and extended Horns Tavern at the junction of Kennington Park Road and Kennington Road [Figs.8&9].

Held under the aegis of the Women’s Liberal Association, this grand event was organised by a distinguished group of patronesses headed by Catherine, the wife of Prime Minister W.E. Gladstone. The Revival, which has never been fully written up, included reconstructions of Vauxhall supper-boxes where visitors could take refreshments, surrounded by illuminations and music, and imagine themselves back at Vauxhall Gardens. It also included a ‘picture gallery and museum’; the museum would have displayed real ‘relics’ from the gardens, such as, for instance the life-sized marble statue of Handel by Roubiliac (owned at that time by the Littleton family of Novello’s the music publishers), and some of the supper-box paintings by Francis Hayman and his studio; the ‘picture gallery’ would have shown images of the Gardens in their hey-day, with topographical prints of the period, but may also have included modern re-imaginings of those buildings of which no prints survived, such as the Coach Entrance itself. The present watercolour is carefully edge-mounted on three sides in what is now a very age-toned piece of cartridge paper – the fourth side, which may have carried information about the artist, title and date, is now sadly missing [see Fig.1], so we have no idea who the artist was. However, the mount must have been introduced so as to make the picture presentable in a display of some sort, maybe in the Vauxhall Revival’s Picture Gallery at the Horns Tavern in Summer 1888. [Fig.10]

As a watercolour of a later date than the building, all the ‘faults’ and discrepancies can be explained. All of the buildings to the west of the gardens (the left of the picture), including the Vauxhall Tap, would have been swept away by the arrival of the railway viaduct in the 1840s; the Proprietor’s House, the Coach Entrance itself, and the pleasure garden were long gone, replaced in the 1860s by three hundred terraced artisans’ houses.

Memories become very fallible after thirty years, and human nature tends to idealise those views of which we hold the fondest memories. Some of the details in this watercolour, however, have the ring of truth about them – the flock of sheep grazing in the ‘coach field’ to keep the grass cropped, the ‘sentry-box’ on the left with its miniature belfry [fig.11], and even that problematic Gothic turret – possibly a half-remembered feature of the Gardens that had actually existed at one time, but is otherwise undocumented.

This attractive image has all the qualities we would expect of a painting done from memory by somebody who might have known the building in their younger days and has romanticised that memory because of what he or she knew was beyond it – the magical world of Vauxhall Gardens, of which they had heard so much from their parents and grandparents but probably never visited themselves. As such it is an entirely valid record of how one feature of Vauxhall Gardens was recalled by local people long after the pleasure gardens had been demolished and replaced with ten streets of houses, a church, a pub and two schools, and Vauxhall had become just another suburban district of London south of the river.

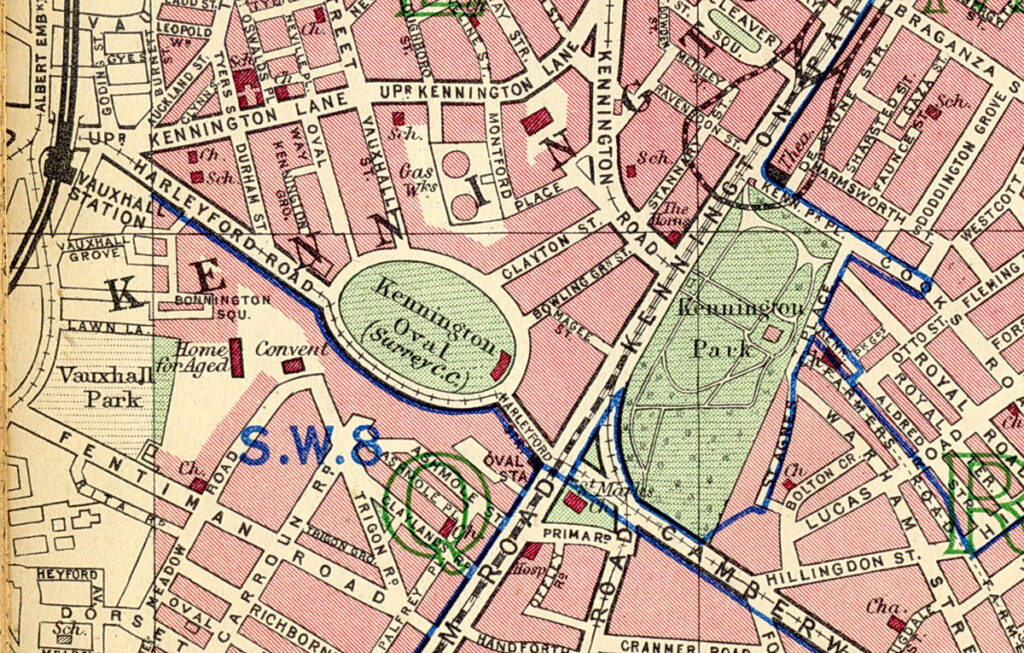

Layers of London

For Vauxhall History’s maps of the layout of Vauxhall Gardens visit the Layers of London website.