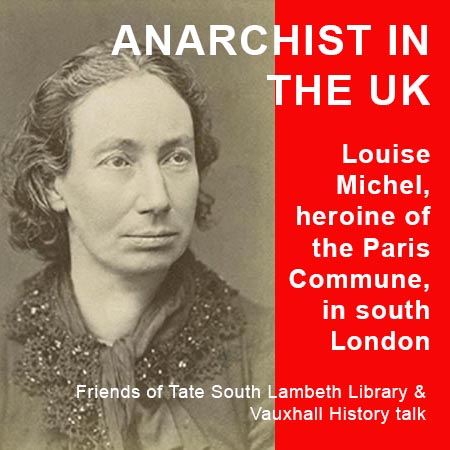

In 1883, Louise Michel, a notorious political radical and veteran of the Paris Commune, was invited to view the Lambeth Workhouse. In this article, published to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the last day of the Commune, 28 May 1881, Vauxhall History co-editor Naomi Clifford looks at the context of the visit and its meaning.

Louise Michel, whose lectures in this country are at present attracting some attention, has paid a visit to Lambeth Workhouse, with the view of inspecting the provision made for the comfort of the aged and unfortunate poor.

South London Press, 13 January 1883, p.12.

On Thursday 11 January 1883, Miss Frances Lord, a newly elected member of the Lambeth Board of Poor Law Guardians, along with “several [unnamed] ladies”, escorted a tall, thin middle-aged Frenchwoman dressed entirely in black around the workhouse in Renfrew Road, Kennington. Lord’s softly spoken and polite guest asked many questions and made a few remarks on the provision for the poor in England compared to France, and afterwards returned to her friends in Fitzrovia. She was the famous socialist and anarchist Louise Michel.

Michel had taken part in the insurrection that led to the establishment of the Paris Commune in March 1871, ten weeks of socialist government established in defiance of the right-wing republic. After its terrible and bloody fall during which, she later admitted, she had set fire to buildings, she was sentenced to hard labour in a penal colony. If that were not bad enough, she was also an enemy of organised religion and an avowed atheist. So, why did Frances Lord invite her to tour the workhouse?

Louise Michel and the Paris Commune

Louise Michel was born out of wedlock in 1830 in Vroncourt-la-Côte, a tiny hamlet in the Haute Marne, about 175 miles south-west of Paris. Her mother was a chambermaid for the local gentry; her father was probably the son of the house, whose family accepted her, brought her up and paid for her education. As a young woman she worked as a schoolteacher, first locally, and later in Paris. From an early age she was attracted to radical ideas about society, women’s rights and the education of children.

By 1860 Michel had moved to Montmartre in Paris, where she opened a school which she ran on her own principles, by which children learned through play and discovery, and without the influence of the Catholic Church. During the 1870 Siege of Paris, when the city was cut off from the outside world by 30,000 Prussian troops camped outside the walls, she ran the vigilance committee for Montmartre, her responsibilities including the provision of first aid (ambulancières) to the National Guard defending Paris and requisitioning and redistributing food to those in need – Paris by then had begun to starve. She joined the National Guard herself, a highly unusual move for a woman, and was active in political clubs, where radical ideas were discussed.

Michel participated in the famous stand-off on 18 March 1871 between government troops and the people of Montmartre. Government troops had attempted to surreptitiously remove the cannon stored on the hill and Michel was among those who actively confronted them. The events of that day led directly to the establishment of the Commune and the subsequent (second) siege of Paris. During the downfall of the Commune at the end of May, often called the Bloody Week (La Semaine Sanglante), Michel was on active duty with the National Guard and she led the defence of the barricade at Clignancourt and in the Père Lachaise cemetery. Afterwards, at a court martial, she was charged with trying to overthrow the government, encouraging citizens to arm themselves, using weapons and wearing a military uniform but remained utterly unrepentant, admitted all the charges and requested the death penalty. Instead she was given a life sentence of hard labour in the French penal colony in New Caledonia in Polynesia.

When the French government granted a general amnesty to Communards in 1880 she was released and made the journey back to France, stopping off in London. It was the start of a growing affection for the city. Although Britain was a monarchy and an empire, forms of administration she detested, she was impressed by its strong tradition of political asylum – there were no immigration restrictions and refugees could not be extradited for political crimes.

London! I love London, where my exiled friends have always been welcomed, London, where old England, standing in the shadow of the gallows, is still more liberal than the French bourgeois republicans are.

Quoted in Bullitt Lowry, Elizabeth Ellington Gunter (eds), The Red Virgin: Memoirs of Louise Michel (2003). University of Alabama Press, p.149.

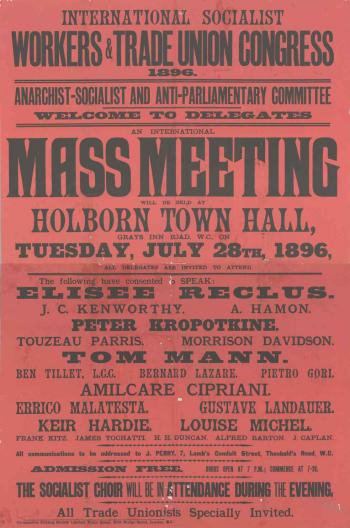

In July 1881 Michel was back in London to attend the Anarchist Congress. The British press was deeply hostile. “Her countenance is full of hate and discontent,” reported the Dublin Evening Telegraph whose “Lady Correspondent” observed her at a public meeting at Cleveland Hall[1]Cleveland Hall, at 54 Cleveland Street, Marylebone, was the centre of the British secularist movement. It is no longer standing.: “Her fingers work in a nervous, agitated manner, and her whole frame is evidently under the influence of internal excitement. She was attired in black, with a cutthroat-looking bow of scarlet ribbon beneath her chin.”[2]29 July 1881, p.4. The Graphic reported that “Mdlle. Louise Michel announced a second Golden Age, and counselled her hearers ‘not to spare their blood in bringing it about.'”[3]23 July 1881, p2. but dismissed the ideas under discussion would ever gain a foothold in Britain. In late 1882 the World labelled her “slightly mad about the revolution”; her rooms in the Boulevard Ornano in Paris, full of “gloom and discomfort”, littered with books, showing “the scholar’s carelessness doubled with the unthrift of poverty;” her clothes were shabby and she was “dreadfully unkempt”.[4]Quoted in Civil & Military Gazette (Lahore), 22 December 1882, p.5.

A visit to the Lambeth Workhouse

On Sunday 7 January 1883, Michel returned to London for a week-long series of 12 lectures at Steinway Hall in Lower Seymour Street[5]The premises, a showroom for pianos and concert hall, were opened in 1875 on what is now known as Wigmore Street. and, as always, took the opportunity to network with potential donors to her projects and, this time, to promote specific causes: education, women’s rights and social justice.

What prompted Miss Lord to invite Michel to see Lambeth Workhouse?[6]We have no direct evidence on whether Lord extended the invitation or Michel suggested it herself. Michel was in high demand, so it is more likely that Lord invited her. Frances Lord,[7]Henrietta Frances Lord (1848-1923)., then aged 34, was a feminist, suffragist and Lambeth Poor Law guardian with a strong social conscience. She had studied at Girton College, Cambridge, and at University College, London. She was a friend of the writer and anti-war campaigner Olive Schreiner, who admired her 1882 translation of Ibsen’s The Doll’s House. Ibsen’s biographer later wrote that it was the playwright’s radicalism that induced Frances Lord to translate his work, which might indicate why she was drawn to Louise Michel.[8]Elizabeth Crawford, The Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928. Routledge, p.357.

Perhaps also Lord had become aware that, rather than the violent overthrow of governments, Michel would be taking women’s education as her theme and that she would also be raising money to fund a shelter for Communards in London who had fallen on hard times. We can speculate that Michel accepted the invitation because she wanted to see how a workhouse with a reputation for humanity operated.

Lambeth Workhouse had not always had a good name. In January 1866 journalist James Greenwood of the Pall Mall Gazette went undercover in the old Lambeth workhouse in Princes Road. His report, ‘A Night in a Workhouse’,[9]12 January 1866, pp.9-10. exposed appalling conditions. He described inhumane overcrowding (30 men in a room under 10 metres square), bloodstained beds and “mutton broth” baths.

No language with which I am acquainted is capable of conveying an adequate conception of the spectacle I… encountered.

James Greenwood on Lambeth Workhouse in 1866.

The new Workhouse complex in Renfrew Road, built five years later at a cost of £42,000, was designed to hold 820 inmates, and included dining halls, a bakehouse, corn-mill, workshops, laundry and engine room. The buildings were heated by open fires and ventilated.[10]See workhouses.org’s page on Lambeth.

The British press was noticeably warmer towards Michel during her 1883 visit than previously. The conservative publication St James’s Gazette, expecting a rough political firebrand, reported instead that she was a “quiet, unpretentious, and well-mannered” woman who advocated, quite reasonably in their opinion, for women’s education to be put on an equal footing as men’s so that they could earn money and keep themselves.[11]10 January 1883, p.6.

On Thursday 11 January 1883, Louise Michel left Fitzrovia, where she was staying with friends, and headed to Waterloo to be met by Miss Lord. They stopped first at the Old Vic in Waterloo, which had recently been revived by Emma Cons, who used it to provide education and cheap performances to working people. Michel and Lord afterwards walked on to Surrey Lodge in Kennington Road, which Cons had helped establish four years earlier as a new way to do social housing, to meet Cons herself and take a look around.

Frances Lord wrote about the visit to the Dwellings for the Westminster Gazette: “She [Miss Cons] told us of their history, their balance-sheet, and their success. Fire-proof walls, coal-box, side-board; as to sports, balconies for play; public wash-house, roofs for drying ground, public meeting room, and, above all, the great central garden for children to romp about in, all told Mdlle. Michel that whoever had thought about all this must be somebody who had worked among the poor for years, and resolved that sooner or later they should have this good thing, at rent within their means, if intelligence and love could give it them.”[12]Frances Lord’s account was reprinted in The Englishwoman’s Review of Social and Industrial Questions, Vol. 14, p.91. London: Office of the Englishwoman’s Review. The women then went on to Lambeth Workhouse in Renfrew Road.

Here they stood in the Relief Hall while the “poor people” filed in for a free meal. Michel inspected the Relieving Officer’s book and Lord explained his duties, which included visiting every new case of destitution to explain that no money would be paid out until the children went to school, and that the Board would pay the school fees. They chatted as they toured the corridors.

“Then no man or woman need starve in England,” remarked Michel.

“Nobody is to starve,” replied Miss Lord. “But sometimes the poor people do not know where to apply, and in some parishes the food is bad, the relieving officers are careless and so on.”

“Yes, of course there will be mistakes, but still there is a meal here for all and a shelter for old age,” said Michel. “Your government is very intelligent to let you all take your part in the work of public institutions, I do not wonder you all love your monarchy and do not wish to change it.”

“I think we are always changing it a very little, but we never knock things down violently, we try to prepare for change. This is the way we women have gradually come to take our modest share in public duty. First we got ready and then we began, it’s no use to start till you’re ready, is it?”

Michel admired some funeral wreaths laid out on a table and Lord explained that the daughter of a former Guardian who was “always so fond of the poor people in the workhouse and came to see them often” had sent them in.

“Was it not good of her to think of them in all her trouble?” said Michel, adding “I understand England.”

That afternoon, Frances Lord accompanied Louise Michel to her next lecture at Steinway Hall. “She said… that those wreaths and the public garden for the children’s play in Surrey Lodge had thrown more light than anything she had ever seen before on the good forces that are always at work in our free country,” said Lord. In the evening, she and Michel dined with the Reverend John Llewllyn Davies,[13]Llewllyn Davies was the father of the children who inspired J.M. Barrie’s stories of Peter Pan. a theologian and Anglican priest active in Christian socialist groups.

Reporting on the visit two days later, the South London Press crowed that “Her visit to Lambeth seems to have inspired her with the idea that in Poor-law matters, they do not ‘do these things better in France.'”[14]13 January 1883, p.12.

On Monday 15 January Michel was back in Paris and continuing her life as a political activist and writer. Two days later, in London, at a scheduled meeting of the Lambeth Board of Guardians, members expressed surprise that Miss Lord had been happy to associate with “a woman of extreme views”. “No doubt she [Michel] had uttered many foolish things,” said Miss Lord in defence of her decision. “But still, like others the reports of her were exaggerated.”[15]South London Press, 20 January 1883, p.5. Despite the personal criticism, Frances Lord had ensured that the work of the Lambeth Guardians had gained useful publicity. Its work had been framed as humanitarian and respectful by one of the severest social commentators of the day.

In France, Michel continued to be harassed by the government and followed by police spies. Two months after her visit to London, in March 1883, she led a demonstration in Paris of unemployed workers during which she encouraged them to loot some bakeries, for which she was sentenced to six years in solitary confinement.[16]She was released after three years. She used the time to write her memoirs.[17]Mémoires de Louise Michel, écrits par elle-même (1886). Paris: F. Roy, available to read in French at Gallica and in English at Google Books. They contain her reminiscences of the day she spent with Frances Lord in Lambeth.

She wrote she had been misunderstood on the subject of workhouses. Her hosts thought she was enthusiastic about them, but that was not the case. “I only stated the pleasure I felt over England’s considering it a duty to be concerned about people who have neither food nor shelter. The thing that struck me—and I immediately said so—was the care with which in some workhouses, Lambeth for example, they soften the refuge where old Albion piles its poverty.”[18]The Red Virgin: Memoirs of Louise Michel, University of Alabama Press (2003), p.148. The Lambeth Board of Guardians were certainly on the right track in terms of kindness and humanity—but for Michel, “the green branches on the old tree cannot rejuvenate the rotten trunk.” She thought a social revolution would certainly take place in Britain, but because there was the outward appearance of care for the poor, it would take longer than elsewhere in Europe.

A life in south London

In 1890, after years of persecution by the French authorities, during which she was imprisoned and forcibly committed to a mental hospital, Louise Michel returned to London, where for the final 15 years of her life she lived semi-permanently. Soon after she arrived, Michel and other exiles established a school in Windmill Street for the children of anarchists.[19]The school moved to Fitzroy Street and closed in 1892 after bombs were found in the basement, probably the work of a police spy who had taken a job as the school’s assistant.

The last phase of her life was highly productive. She frequently appeared at radical and socialist rallies and poured out articles, memoirs and poetry. Initially she lived in Fitzroy Street in Fitzrovia (where French exiles tended to cluster), moving to East Dulwich in about 1894, and later to Sydenham and Streatham.

Michel was a popular speaker on both sides of the channel and her name continued to have major pulling power at radical and socialist meetings. She regularly returned to France to give speaking tours and it was on one of these that she fell ill, dying in Marseilles of pneumonia at the age of 75. She was buried in the Levallois-Perret cemetery in Paris. Her funeral was attended by 100,000 people.

Further reading and useful links

Naomi Clifford’s talk on Louise Michel in south London, for Vauxhall History and Friends of South Lambeth Library, is available to watch on YouTube

https://youtu.be/k9g69r-P9m0

Transpontine blog on Louise Michel’s places of residence in south London http://transpont.blogspot.com/2014/05/louise-michel-paris-communard-in-south.html

The classic biography of Louise Michel is by French historian Edith Thomas (published in 1971). It is available in an English translation to borrow from archive.orghttps://archive.org/details/louisemichel00thom/

Paul Foot’s remarkable 1979 lecture on Louise Michel. If you are not an SWP supporter, don’t let some of the rhetoric put you off.

https://youtu.be/IfQojkzsikE

In Our Time on the Seige and Commune of Paris (BBC Radio 4 – with Melvyn Bragg) https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000d8rv

Watch out for the publication of Duncan Bowie’s forthcoming book on Dulwich radicals for the Dulwich Society. It will include a chapter on Louise Michel.

References

| ↑1 | Cleveland Hall, at 54 Cleveland Street, Marylebone, was the centre of the British secularist movement. It is no longer standing. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | 29 July 1881, p.4. |

| ↑3 | 23 July 1881, p2. |

| ↑4 | Quoted in Civil & Military Gazette (Lahore), 22 December 1882, p.5. |

| ↑5 | The premises, a showroom for pianos and concert hall, were opened in 1875 on what is now known as Wigmore Street. |

| ↑6 | We have no direct evidence on whether Lord extended the invitation or Michel suggested it herself. Michel was in high demand, so it is more likely that Lord invited her. |

| ↑7 | Henrietta Frances Lord (1848-1923). |

| ↑8 | Elizabeth Crawford, The Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928. Routledge, p.357. |

| ↑9 | 12 January 1866, pp.9-10. |

| ↑10 | See workhouses.org’s page on Lambeth. |

| ↑11 | 10 January 1883, p.6. |

| ↑12 | Frances Lord’s account was reprinted in The Englishwoman’s Review of Social and Industrial Questions, Vol. 14, p.91. London: Office of the Englishwoman’s Review. |

| ↑13 | Llewllyn Davies was the father of the children who inspired J.M. Barrie’s stories of Peter Pan. |

| ↑14 | 13 January 1883, p.12. |

| ↑15 | South London Press, 20 January 1883, p.5. |

| ↑16 | She was released after three years. |

| ↑17 | Mémoires de Louise Michel, écrits par elle-même (1886). Paris: F. Roy, available to read in French at Gallica and in English at Google Books. |

| ↑18 | The Red Virgin: Memoirs of Louise Michel, University of Alabama Press (2003), p.148. |

| ↑19 | The school moved to Fitzroy Street and closed in 1892 after bombs were found in the basement, probably the work of a police spy who had taken a job as the school’s assistant. |