A recent discovery among a batch of printed ephemera from Victorian Vauxhall by Vauxhall History co-editor and co-author of Vauxhall Gardens: A History David Coke throws new light on the life of a remarkable resident of Kennington – the conjuror and collector Henry Evans Evanion (1832-1905).

Evanion’s vast and wide-ranging collection of playbills, prints, advertisements and other ephemera associated with the Victorian entertainment scene in England is well known; the bulk of it was purchased by the British Museum in 1895, but other museums, libraries and private collections across the world hold large numbers of further items from it.

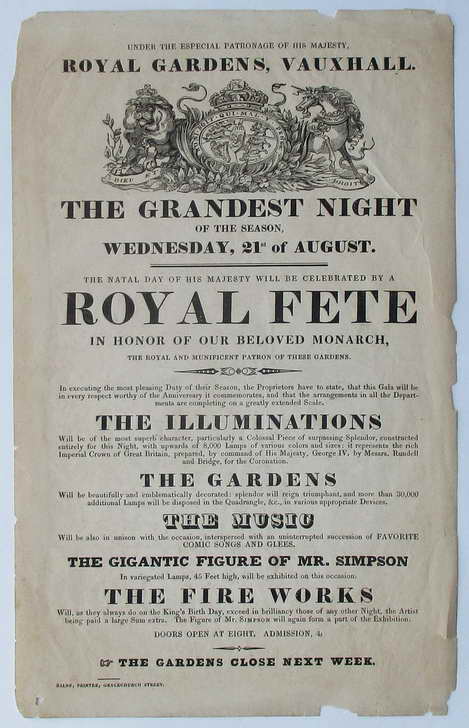

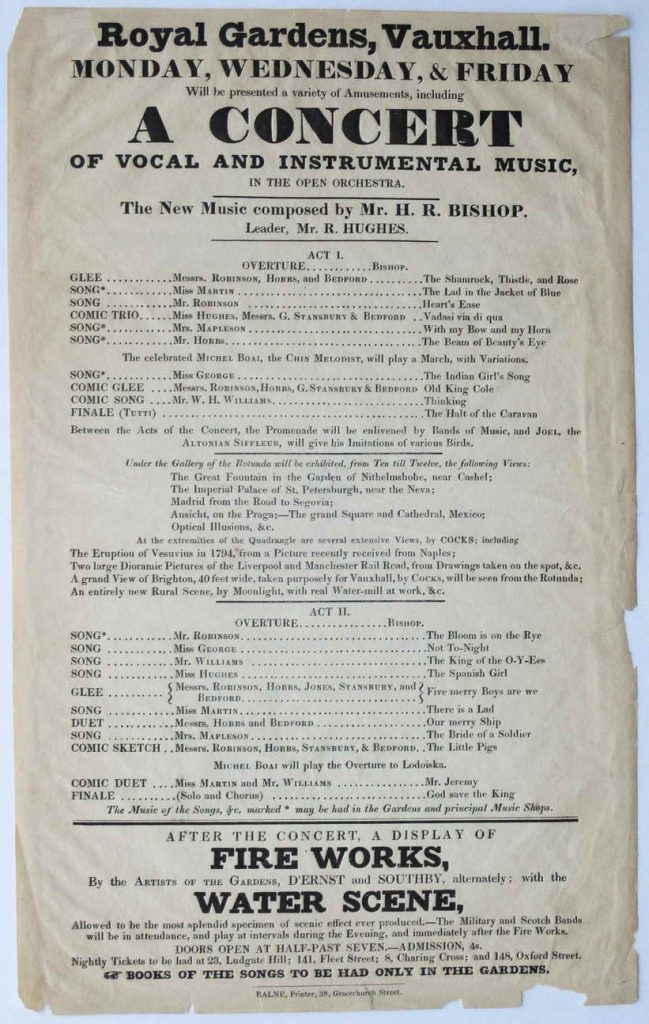

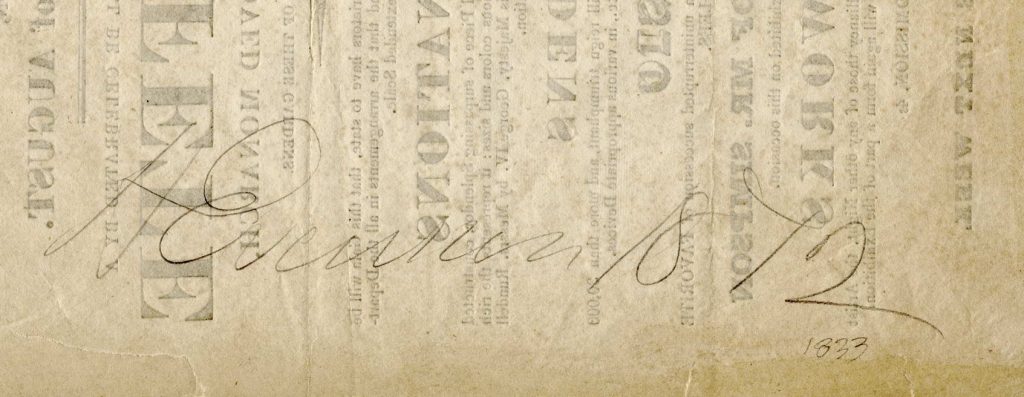

This Evanion discovery, which throws new light on Evanion’s family and his collecting, consists of (i) a pencil signature on the back of a Vauxhall Gardens handbill advertising the ‘Royal Fete’ on 21 August 1833 (Fig.2) and (ii) a brief autobiographical note in the same hand scribbled in pencil on the reverse of another handbill, this one advertising a concert series in 1831. The signature (i) reads ‘H. Evanion 1872’; the significance of the date is unclear, although the official change of his surname from Evans to Evanion had only recently taken place, so may just have been trying out his new signature. (Fig. 4). The autobiographical note on the back of the 1831 handbill (ii) is less easy to decipher, but has now been transcribed as follows: “I was Connected with / Vaux’ Gardens from / 1840 to 59 / Also my Grandfather & / Father. / H. Evanion Collection / of Bills, Prints, Letters, / Letterpress, remarks, posters / and Advertisements / Continued to collect 1846 / up to 1888 5 Collections / the Best sold to Mr. Muset / 1888.” (Fig. 5). The writing of ‘Mr Muset’ is obscured, so the reading of this name may be wrong.

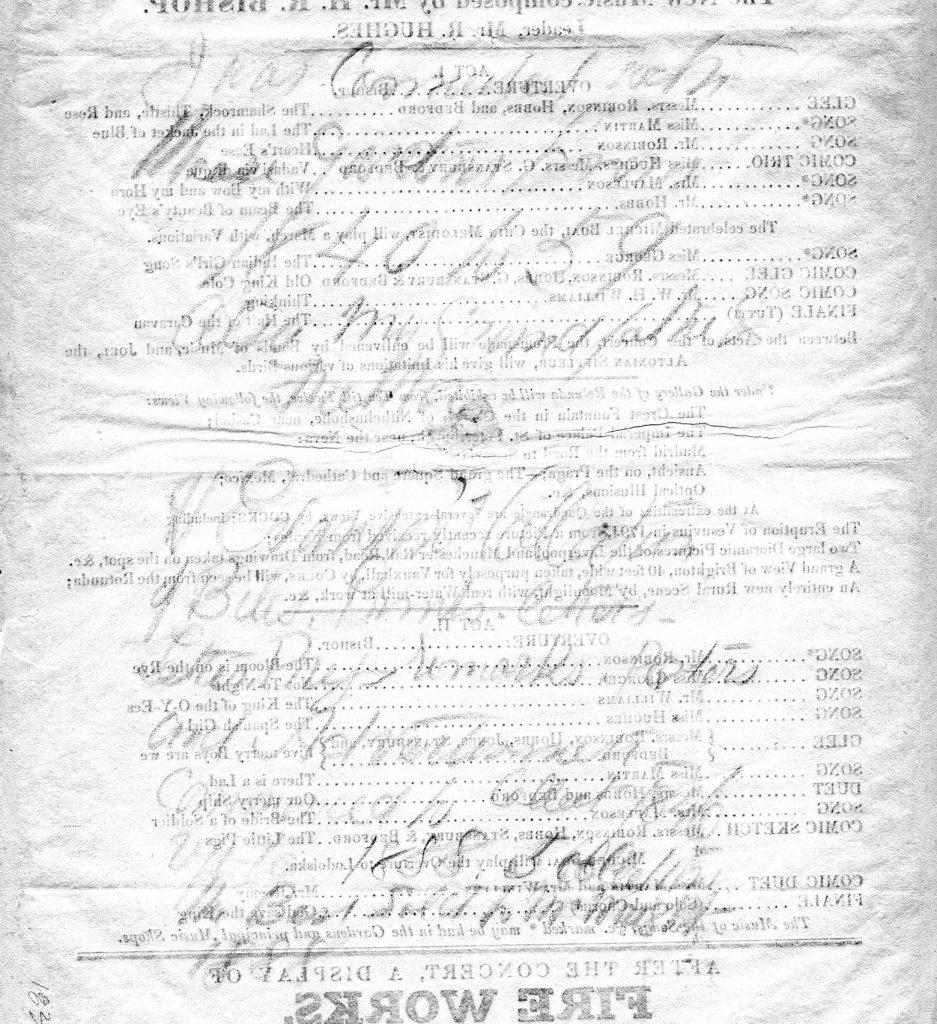

Fig. 2: Handbill (i) for a ‘Royal Fete’ at Vauxhall Gardens in 1833 [CVRC 0832].

Fig. 3: Handbill (ii) for an 1831 concert series at Vauxhall Gardens [CVRC 0833].

Fig. 4: Evanion’s signature on the reverse of Fig.2. The significance of the date ‘1872’ is unclear.

Fig. 5: Evanion’s autobiographical note on the reverse of Fig.3.

The autobiographical note, brief as it is, gives several new facts about Evanion. First, it states that his father and grandfather were both involved at Vauxhall Gardens; second, it affirms that his collection began seriously in 1846, when he was just 14 years old, and, finally, that he sold many of his best items to an unidentified ‘Mr. Muset’ in 1888. Evanion would have considered his ‘best’ items to be those most closely related to conjuring and magic, especially those with illustrations. Vauxhall letterpress handbills of the 1830s and 1840s would not have been highly valued even by Evanion, although today many of them are vanishingly rare or even precious unique survivals.

It is likely that the mysterious buyer, ‘Mr. Muset’, mentioned in Evanion’s note was the ‘wealthy collector in Paris’ who bought the part of Evanion’s collection previously seen by H.H. Montgomery, the cleric and historian[1]Henry Hutchinson Montgomery, The History of Kennington and its Neighbourhood, London: Stacey Gold 1889, p.86.. From the available evidence it appears that this was at least part of the collection that was later acquired in France by Robert Gould Shaw and presented by him in 1915, bound into nine elegant volumes, to the Theatre Collection at Harvard University, of which Shaw himself was the first curator. [2]Harvard Theatre Collection, TS 952.2F.

Both items with the Evanion manuscript on the back were acquired as part of a group of ten Vauxhall Gardens handbills, at the estate sale of the collector Stephen O. Saxe, of White Plains, New York by an American collector, and have since been repatriated to the UK. It is possible that other items in the group derive from Evanion’s collection, but the only evidence for this would be their unusually fine condition. Stephen O. Saxe (1930-2019) had been a set designer for stage and television, but on his retirement in 1985, his abiding interest in 19th-century typography and printing was allowed free rein, leading to published books and articles, to the founding of the American Printing History Association (APHA), and to an extensive collection of print samples, typefaces and even presses. His collection, and his encyclopaedic knowledge, were generously and happily shared with many other interested parties. Saxe was too young to have acquired these items directly from Evanion, but, from their unusually good state of preservation, it is clear that they were in one or more similar but unidentified collections between 1905 and the 1980s; the private collections of Arthur J. Margery (1871-1945) and James B. (Jimmy) Findlay (1904-1973) are both known to have held items from Evanion’s collection. [3]James Black Findlay, ‘Evanion’ in The Sphinx magazine, vol.XLVIII, no.11, Jan.1950, 291-4. Saxe could well have acquired these items in the UK from Findlay’s estate.

Most such Vauxhall ephemera has suffered much worse treatment than these pieces, because they were cheaply printed on lightweight paper, and then either pinned or pasted on walls or billboards in all weathers, or handed out in the street, and finally thrown away as worthless (Fig.6). These handbills were intended to last no more than a few days. The fact that these items from Saxe’s collection have lasted almost two hundred years is partly due to the fact that Henry Evans’s family was directly involved at Vauxhall Gardens as suppliers of refreshments for at least two generations before Henry was born. The young Evanion is bound to have accompanied his father and grandfather on their delivery trips to the Gardens, and is likely to have picked up handbills himself, or been given them by indulgent members of staff. If he was only eight years old when these visits began in 1840, as stated in his note shown in Fig.5, it is likely that this is how his collection began, possibly with an illustrated handbill of something like a balloon ascent by Charles Green, or of one of the famous Vauxhall firework displays, that the boy found lying around in a back-room. No value was attributed to such throw-away items once the performance had taken place, so they became so much scrap paper. It is not impossible that Henry’s obsession with collecting, as well as his fascination with performance, juggling, and sleight of hand were both inspired by Vauxhall’s brilliant 19th-century spectacle and performers.

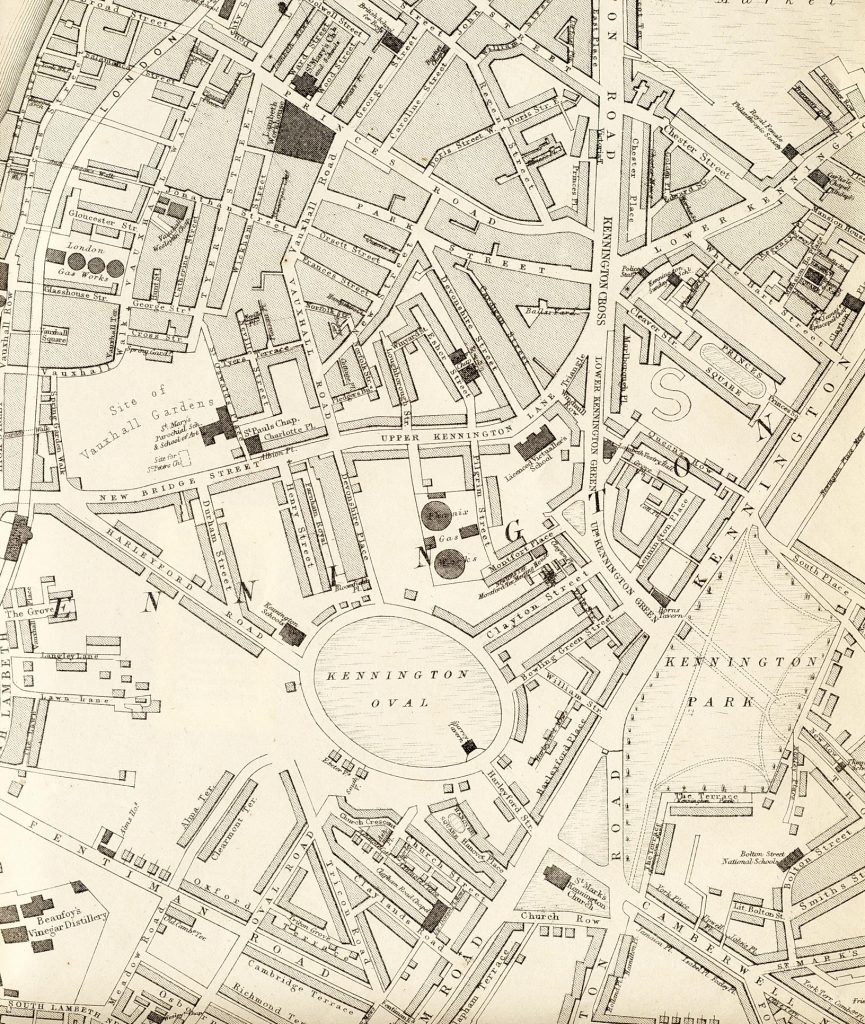

Henry Evans was the eldest son of Thomas (1810-c.1849) and Susan Evans (1810-c.1883), confectioners and victuallers of Kennington Lane. In the 1841 census, Henry is recorded at the age of about 10 living with his parents and his brothers Robert (8 years old), James (6) and Thomas (3), at Windmill Row, Upper Kennington Lane (south of the intersection of Kennington Lane and Kennington Road) (Fig.7). Only seven years later, he had launched his career as a conjuror, illusionist, ventriloquist and juggler; his first professional engagement was at the Rock Inn, Kemp Town, Brighton, as a support act to a ventriloquist called Newman and his family. In the same year, he put on a solo show called a ‘Soiree Fantastique’ at the Town Hall in the small town of Langport in Somerset; he played many such towns and villages around the British Isles during his career.

Since childhood Evans had practiced magic tricks on a makeshift stage in the loft of his family home to audiences of his friends and brothers, before becoming a professional magician, working on his own and with the Newman family. In the 1860s, he performed three times for members of the royal family, at Sandringham and at Marlborough House; amongst his illusions on the noted occasion at Sandringham was ‘The Grand Feat of the Globes of Fire, Fish and Birds’.

In the 1850s, Evans started to use the professional name Evan Ion, maybe in tribute to a perceived Welsh ancestry, but later that decade it was clear that his act needed a more exotic headline, so he contracted the name to ‘Evanion’, at the same time adopting a French accent during his act. His illusions and ventriloquism always included an element of humour, which proved popular with audiences, whether schoolchildren or members of the royal family. A review of an Evanion performance published in the Morning Advertiser of 23 December 1873 states that:

trick followed trick with wonderful rapidity, and a profusion that speaks highly for Mr. Evanion’s resources. He is not only a very skilful professor of the art of legerdemain, but he is happy in possessing a rich vein of comic humour, which he infuses largely into his conversation either with the spectators or with the assistant whom he summons from among the spectators and the result is to excite laughter as well as wonder.

Henry later took on the name Evanion as his legal surname.

Evanion’s advertising posters not only capitalised on his royal connection, but also made big claims for his act. In one poster now in the British Library, he proclaims, in the manner of a music-hall ’barker’, “Mr Evanion, who, alone, unaided by confederates, and without all the ordinary apparatus, Deceives the Eye, amazes, bewilders, and baffles the keenest observer, will display his truly miraculous Acquirements in Prestidigitation which surpass everything hitherto presented to the Public, in fact exhibiting powers that seem impossible to be achieved by human agency.” A ticket of 1865, also at the British Library, calls his act a ‘Wonderful and amusing entertainment . . . Exhibiting Startling and Extraordinary Illusions, Laughable Ventriloquial effects & Necromantic Feats. Something New under the Sun.’

Whether his act lived up to all these claims is unclear, but he does appear to have had a long career in magic, with some modest success, and was still active, according to his publicity, until his final illness. His income, however, was never sufficient to tempt him to abandon his father’s confectionery business at 221 Kennington Road (just north of the junction with Chester Street, now Chester Way).[4]Elizabeth Harland, ‘The Evanion Collection’, British Library Journal, vol. XIII/1, Spring 1987, p.65. And Post Office Directories, 1875-1890. Having said that, it is clear that his fees for an evening’s entertainment were of a professional standard. One of Evanion’s advertising handbills that must date from the 1880s gives his fees as either five guineas, three guineas or two guineas for a two-hour evening entertainment for children. The price depended upon the selection of illusions and magic to be performed, but all three included ‘Distributions of Presents, Programmes &c.’ It is known that his drawing room show for adults was charged at ten guineas.[5]J.B. Findlay, ‘Evanion’, in The Sphinx, vol. XLVIII/11, Jan. 1950, p.291.

It was probably a similar type of ‘Drawing-Room’ show that Evanion performed at the Crystal Palace in Sydenham during a series of six shows at the end of 1880, for which he received half the takings at the door, which came to £20 7s.6d. Later shows at Sydenham, which appears to have been a regular fixture for Evanion, included his ‘Extraordinary Flag Illusion’, as well as ‘The Japanese Marionette’, ‘The Mystic Parrot’, The ‘Fan Fan Enchantment’, ‘Vulcan’s Chain’, the ‘Extraordinary Experiment of Wireless Telegraphy by Cards’. and the ‘Japanese Lady’s Reception’.[6]J.B. Findlay, ‘Evanion’, in The Sphinx, vol. XLVIII/11, Jan. 1950, illustrations on pp.293 & 294.

Bookings like the Crystal Palace would no doubt have been highlights in Evanion’s career, with long periods of no magic work at all. It is likely that Henry’s mother Susan, and then his wife Mary Ann in fact provided most of the family income by running the confectionery business for him, while he was happily occupied with his stage-work, whether performing, lecturing or rehearsing, or else researching the history of magic at the British Museum Reading Room, where he spent every spare hour, presumably much to the frustration and irritation of his long-suffering wife. Henry and Mary Ann (née Evans) had married in 1865 at St Mark’s church, Kennington; there is no record of any children born to the couple. Mary Ann, who was three or four years younger than her husband and may have been related to him, appears initially to have accompanied Henry in his act, being called a ventriloquist in her own right, but the confectionery business would have been a full-time occupation for her from the time when her mother-in-law Susan was no longer able to work; it would therefore have made sense for her to give up performing and to do what she could to support herself and her husband, and to look after the widowed Susan in her old age.

It was already known that T.H. Evans, Evanion’s father Thomas Henry Evans, had been a ‘Punch-maker for upwards of twenty years to the ‘Royal Property’’ (i.e. The Royal Gardens, Vauxhall).[7]Harvard Theatre Collection, Shaw Volumes, VIII p.85, 1859. It was also known that ‘Henry Evans of Kennington Lane’ was supplying ‘Ices and Confectionary’ to the Gardens in the 1850s[8]George Stevens’s Vauxhall account books in the Lambeth Archive, W/162/7., and that a Mr Evans (maybe Evanion himself, or one of his brothers) was, in 1854, helping to staff Vauxhall’s Lower Bar, at a salary of £1 1s. per week, and looking after the reserved seats at 15 shillings a week. Thomas Henry Evans the punch-maker, had also been the landlord of the Black Prince public house in Prince’s Road, until April 1849; but the ‘Henry Evans of Kennington Lane’ who supplied ice cream and confectionery must be a reference to Evanion himself and his wife Mary Ann carrying on his parents’ trade. Henry had, after all, become a professional pastrycook by the time he was twenty years old, following in his father’s footsteps. Without his family business as a supplier to Vauxhall Gardens, it is likely that Evanion would not have been able to carry on his career in magic.

The role played by Henry’s grandfather at Vauxhall, as mentioned in the autobiographical note, is undocumented, but presumably also related to the provision of refreshments from around 1800. In the 1841 census, Thomas and Susan Evans and their four sons are living next door to Thomas and Jane Evans, both aged 60, and Thomas Sr is described as a fruiterer. These must be Henry’s grandparents, because ten years later, that same Thomas Sr., by now a pastrycook, and his wife Jane are living at 1 Upper Kennington Lane, with Evanion’s mother Susan, and three of her sons – the 20-year-old Henry himself, by now fully qualified as a pastrycook, and his younger brothers Robert and James, aged 18 and 17, probably both at work in the family business. As a fruiterer, Thomas the elder could have supplied Vauxhall Gardens with the oranges and lemons that were usually on the bills of fare, as well as fruit for tarts and pastries, and for the notorious Arrack punch (supplied for two decades by the Evans family) as well. By 1851, Evanion’s father, Thomas the younger, had disappeared from the records, so had presumably died, which may be the reason why the Black Prince pub needed a new landlord in April 1849. Another ten years on (1861) and the widowed Susan is living with her sons Henry and James (by now a painter and decorator) at 26 Park Place; this was a curved terrace of houses on the north side of Kennington Lane opposite Windmill Row (see Stanford’s 6-inch Library Map of London and its Suburbs, 1862). Henry’s other brother Robert had married and set up his own household by 1860. No trace of Henry’s youngest brother Thomas can be found after the 1841 census, when he was just 3 years old.

Henry Evans Evanion lived in Kennington all his life, moving house several times within a small circuit, from his parents’ house on Windmill Row, first to his grandparents’ house at 1 Upper Kennington Lane, then with his mother and brother James to Park Place (Kennington Lane), then, following his marriage, to 18 Pilgrim Street, where Montford Place is now, next to the Pilgrim pub (in the 1871 census), then to 22 Kennington Road according to the 1890 Electoral register (see map at Fig.7 for locations); in the 1891 census, Henry and Mary Ann are shown living at 9 St Anne’s Road, where Robert Evans, a widower, was also living with his adult son and daughter; this Robert, described as a ‘Theatrical Employee’ in the census, must be Henry’s brother; as Robert had lost his wife, and Henry may have been in financial difficulties, it is likely the brothers thought it would make sense for them to share a house. St Anne’s Road, between Brixton Road and Clapham Road, just south of The Oval (and just off the map in Fig.2), was renamed Southey Road in 1937; this was the only time Henry’s home was marginally outside Kennington’s boundary. Henry and Mary Ann had moved to their final home, back in Kennington proper, at 12 Methley Street well before the next census in 1901.

It was at Pilgrim Street in 1871 that we see Henry’s legal surname given as ‘Evanion’ rather than Evans for the first time, much to the confusion of the census-taker, who has to make several attempts at his name. It is also here that his occupation is first given as a ‘Professor of Legerdemain’ (sleight of hand), and Mary Ann’s as a ventriloquist. His mother Susan is still alive, aged about 63, and still at work in the family’s confectionery business. In 1871, Henry and Mary Ann had been joined at Pilgrim Street by Charlotte Puris, Henry’s 64-year-old aunt who was a mantle-maker[9]A dress-maker, specialising in ladies’ tailoring.. By the time of the next census, in 1881, Susan has taken Charlotte’s place with Henry and Mary Ann, and the family appears to be living over the shop at 221 Kennington Road. Mary Ann herself is by this time being called a confectioner in her own right, suggesting that she was by now running the family business in Susan’s place.

The closure of Vauxhall Gardens at the end of the 1859 season must have been a cruel blow to Evanion’s family, as they lost their best customer, and an assured source of summer income. Evanion himself would have lost a great source of free material for his collection as well, although he may have been allowed to sort through the scrap paper store before it was used to light the bonfires during the demolition of the gardens. In addition, Evanion lost his regular contact with all those clowns, jugglers, mimics, contortionists, ventriloquists, ball-walkers, fortune-tellers, tight-rope artists and magicians, who performed at Vauxhall in the last three decades of its life. After 1859, though, the confectionery business did survive, first under Susan’s care, and then under Mary Ann’s; the site of Vauxhall Gardens was built over with houses, schools, pubs and a church, providing many new potential customers, although the new inhabitants were largely in the lower income brackets, so expenditure on luxuries like sweets and pastries would have been strictly limited. There is no doubt that the business suffered, and the several house moves made by Henry and Mary Ann suggest a downward trajectory in their fortunes; it appears that they only narrowly avoided destitution at the Lambeth Workhouse.

In the last year of Evanion’s life when he was very ill with cancer and in dire poverty, he met and became a friend of Harry Houdini, who admired Evanion’s collection hugely, especially the ephemera associated with the great magicians of the past including Robert-Houdin, Katterfelto, Boaz, Breslaw, Pinetti and others. Houdini purchased many items from Evanion for his own collection, partly in order to support him in his old age, poverty and sickness[10]Harry Houdini, The Unmasking of Robert-Houdin, New York, the Publishers Printing Co., 1908. Houdini later remembered Evanion as a dear old friend who had introduced him to a vast range of fascinating characters through his collection. Houdini’s own collection of ephemera, including numerous items bought from Evanion, is now largely held at the US Library of Congress, and at the University of Texas (Harry Ransom Center).

Apart from the sales to Houdini and to the Parisian collector, Evanion in his poverty had also sold a large part of his collection to the British Museum Department of Printed Books (now the British Library) in 1895. This was done in two tranches, on 5 July and 3 October, and amounted to around 6,000 items in all. The British Museum curators, at that time, had to have the trustees’ approval for any purchase over £20, so the Evanion Collection was acquired for just under that sum, in order that it did not have to be reported to the trustees, who would have considered it beneath their notice or interest. Since all these sales had been to provide funds for the impoverished husband and wife, the £20 from the British Museum, and the apparently paltry sums given by Houdini, would not have gone very far to support the couple in their old age.

It is to be hoped that the ‘wealthy collector in Paris’ was more generous, but this, sadly seems unlikely, for, as Houdini himself tells us, at his first meeting with Evanion, when the famous escapologist was on tour in London in 1904, Evanion appeared as ‘a bent figure, clad in rusty raiment’, who the hotel’s concierge had not dared to send up to Houdini’s suite because he appeared so shabby. As a result, Evanion had been kept waiting for three hours in the hotel lobby before the two men eventually met. Evanion stood with difficulty and approached Houdini ‘with some hesitancy of speech but the loving touch of a collector’ as he opened the parcel of ‘treasures’ he had brought as bait for the great man. The bait worked, and Houdini, despite a bout of influenza, rushed over to Evanion’s home early the following morning. The two men pored over Evanion’s collection, and became so deeply engrossed in it that Houdini was missed that evening at the hotel, and he had to be dragged away from Evanion’s basement home in Methley Street by his brother and his doctor at 3.30 the following morning.

Houdini visited Evanion for the last time at his Methley Street home, on 7 June 1905, only ten days before his old friend died of throat cancer at St Thomas’s Hospital. Methley Street, of course, is now famous as the childhood home (if only briefly) of another entertainer who knew all about severe poverty and deprivation, Charlie Chaplin. When Harry Houdini, on his visits, saw how low Evanion had sunk and how sick he was, the great man quickly set up a fund for his benefit through an advertisement in The Encore magazine, donating five pounds himself. All too soon this fund had to pay for Evanion’s funeral, with the residue going to his widow, Mary Ann, who survived him by just a few months.

Evanion’s chief legacy today is his vast and all-embracing collection of Victorian entertainment ephemera, which has been, and continues to be, of inestimable value to scholars and amateurs of the many subjects that it covers. The young Henry Evans and his wife Mary Ann would be staggered that, a century later, single items that he picked up in the back rooms of Vauxhall Gardens for nothing now sell for many times the £20 he received from the British Museum for his entire collection of 6,000 items.

David E. Coke

I gratefully acknowledge the invaluable assistance of Karen Coke in her determined and patient research into Evanion’s family; this is all new research, not included in previous biographies.

Further reading online

Untold Lives: Evanion the Royal Conjuror Plays With Fire

Elizabeth Harland on the Evanion collection at the British Library

The Unmasking of Robert-Houdini, by Harry Houdini

References

| ↑1 | Henry Hutchinson Montgomery, The History of Kennington and its Neighbourhood, London: Stacey Gold 1889, p.86. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Harvard Theatre Collection, TS 952.2F. |

| ↑3 | James Black Findlay, ‘Evanion’ in The Sphinx magazine, vol.XLVIII, no.11, Jan.1950, 291-4. |

| ↑4 | Elizabeth Harland, ‘The Evanion Collection’, British Library Journal, vol. XIII/1, Spring 1987, p.65. And Post Office Directories, 1875-1890. |

| ↑5 | J.B. Findlay, ‘Evanion’, in The Sphinx, vol. XLVIII/11, Jan. 1950, p.291. |

| ↑6 | J.B. Findlay, ‘Evanion’, in The Sphinx, vol. XLVIII/11, Jan. 1950, illustrations on pp.293 & 294. |

| ↑7 | Harvard Theatre Collection, Shaw Volumes, VIII p.85, 1859. |

| ↑8 | George Stevens’s Vauxhall account books in the Lambeth Archive, W/162/7. |

| ↑9 | A dress-maker, specialising in ladies’ tailoring. |

| ↑10 | Harry Houdini, The Unmasking of Robert-Houdin, New York, the Publishers Printing Co., 1908. |