by David Coke

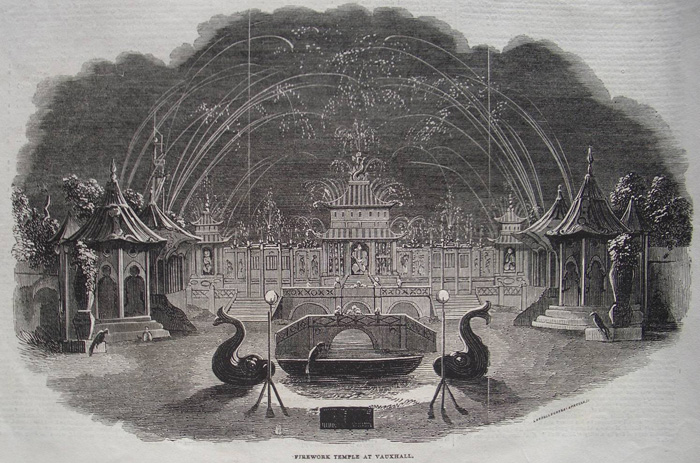

The Firework Temple

Of all the correspondence that I receive about Vauxhall Gardens, some of the most memorable comes from descendants of the people who performed or sang at the gardens. Striking among these are the descendants of firework-makers, of whom Vauxhall employed a dozen or more between 1798, when the first regular displays started, and 1859, when the gardens finally closed. And it transpires that several of the fire-workers were women, working in a fantastically dangerous and skilled craft. At least two of these women – Madam Hengler and Madam Coton – were more than skilled craftsmen, and themselves directed the fireworks at Vauxhall over significant periods. The protagonists in the following stories are the direct ancestors of two of my correspondents.

Great rivalries sprang up between the various fire-workers, inevitably encouraged by the proprietors of the gardens who wanted the grandest possible displays. But these rivalries were also dangerous, and people would take risks to achieve better results, and may even have committed acts of sabotage to undermine their rivals.

The first great fire to be associated with Vauxhall’s performers occurred in 1818, when a mysterious series of explosions destroyed the factory of Signor Vincento de Mortram in Mead Place, St George’s Fields, Southwark, leaving Mortram’s competitor, Sarah Fields, better known as Madam Hengler, in sole charge of the Vauxhall fireworks for three years. Her husband, who died in 1802, had also displayed fireworks at Vauxhall, followed later by their son, who went on to help found Hengler’s Circus. Apart from his factory, the only recorded casualty of Mortram’s fire was an unfortunate pet monkey, who had been chained to the building and so could not escape.

Madame Hengler

Mortram was re-engaged in 1821, and collaborated with his rival Mrs Hengler on the production of the spectacular ‘Eruption of Mount Vesuvius’ for Vauxhall. However, in the previous year, there had been a huge explosion and fire at the home and firework factory of a Mrs Jones, whose husband called himself ‘Assistant Fire-Worker at Vauxhall Gardens’; he was probably the same Mr Jones who was Madam Hengler’s son-in-law, and it was Mrs Jones who was the only occupant of the factory at the time of the fire. She was fortunately pulled out of the burning building by a neighbour, Mr Holmes, but she was severely injured, and was taken off to hospital ‘with little hope of recovery.’ Whether she recovered or not is not recorded, but Mme Hengler’s daughter, also Mrs Jones, certainly lived on and was involved in yet another nasty fire in 1845; on 9 October at 7.30 in the evening, fire broke out in her premises at Asylum Row, Westminster Bridge Road, probably caused by the carelessness of a boy trimming a lamp near a load of squibs. Four women, four children and a man were all working on the first floor, tying fireworks, and all escaped. However, Mrs Jones’s mother-in-law, the eighty-year-old Sarah Hengler, who had retired from Vauxhall twenty years earlier, was dozing in her chair, and could not move, due to her corpulence and disabilities. She was burned alive, screaming, having hauled herself almost to the window. A particularly cruel, if not inappropriate end for Thomas Hood’s ‘Starry Enchantress of the Vauxhall Garden . . . The Professor of Fiery Necromancy.’ A verdict of accidental death was recorded by the coroner, and several newspapers and periodicals, including ‘Punch’ ran glowing obituaries.

The last fatal fire associated with Vauxhall destroyed the Westminster Bridge Road premises of Mrs William Bennett, better known as Madam Coton, in August 1858, just a year before the gardens closed. Four people were killed in the explosion as well as a neighbour, Sarah Williams, one of the many ‘innocent bystanders’ who lost life and property in this series of fatal accidents.

It is not a great surprise to read in press cuttings of the time that the Vauxhall Firework Tower was itself destroyed by fire soon after midnight on 2 July 1837, although without causing any injuries. It was apparently the duty of the firemen employed at the gardens to hose down the firework stage from their engine following every performance. Whether this duty had been carried out on that Saturday night is not known. The fire, which raged for more that two hours before the Kennington Cross division managed to bring it under control, also destroyed the painting room, and 14 or 15 trees were burned to the ground, with up to 30 badly damaged. The fire inevitably drew huge numbers of spectators, many of whom broke into the gardens to gain a ringside seat, so adding to the damage. ‘The damage done will fall on the Phoenix Fire Insurance Office to the full extent’ we are told. The fire did not prevent the gardens reopening on the following evening.

A lot more work needs to be done on the Vauxhall fireworks, especially on the part played by women in their manufacture and display, and on the area around St George’s Fields (now the site of St. George’s catholic cathedral, opened in 1848), which appears to have been a favoured area for these lethal factories, whether associated with Vauxhall or not.

David Coke

The author would like to acknowledge the help of David Stabb and Laurence Mortram in the preparation of this article for The Vauxhall Society.

© David Coke, 23 November 2010