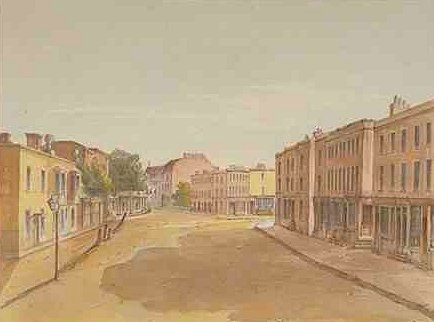

Entrance to Vauxhall Gardens

Under Charles II public entertainments were once more became fashionable and England strove to outdo the extravagances of the court of Charles’s French cousin Louis XIV. In 1661 the famous garden at Vaux-le-Visconte, designed by Andre Le Notre, was opened with a fete in honour of the young king, and in the same year the ‘New Spring Garden’ at Vauxhall opened to the public.

At first it expected to provide their own entertainment. John Evelyn visited the New Spring Garden on 2 July 1661, and Samuel Pepys records in his Diary, under 29 May 1662; ‘I took the boat, and to Fox-hall, where I had not been a great while. To the Old Spring Garden, and there walked long, and the wenches gathered pinks. Here we staid, and seeing that we could not have anything to eat but very dear, and with long stay, we went forth again without any notice taken of us, and so we might have done if we had anything. Thence to the new one,’- the New Spring Garden -‘ where I never was before, which much exceeds the other; and here we also walked, and the boy crept through the hedge and gathered abundance of roses, and after a long walk, passes out of doors as we did in the other place. In the following year the French traveller, Balthazar Monoconys, describes the ‘Jardin Printemps’ as ‘lawns and gravel walks dividing squares of twenty to thirty yards enclosed with hedges of gooseberry trees within which were planted raspberry bushes, rose bushes and other shrubs, as well with herbs and such vegetables bordered with jonquils, gills flowers, or lillies, led to numerous arbours or little supper boxes where the visitors could partake of a cold collation’. It was also in 1663 that George Villiers, the second Duke of Buckingham, was granted letters patent for the establishment of a glassworks at Vauxhall. The glassworks, which was situated just to the north of the Spring Garden, was under the direction of Venetian craftsmen introduced by the Duke, and among its products were plate glass for the windows of carriages and mirrors glass.

Sir Samuel Morland, Master of Mechanics to King Charles II, who had earlier acquired the old Manor House of Vauxhall, demolished it and built himself a new house on the site. In 1665 he acquired the Spring Garden, adjoining Copt Hall. John Aubrey, writing in Antiquities of Surrey, records that Morland built “fine room at Vauxhall the inside all of looking-glass, and fountains very pleasant to behold; which is much visited by strangers. It stands in the middle of the garden, covered with Cornish slate.

Doctor Jonathan Swift visited the Garden on 17 May 1711, and Addison, writing in The Spector of Tuesday 20 May 1712, describes a visit to Vauxhall in the company of Sir Roger de Coverley:

As I was sitting in my chamber, and thinking on a subject for my next Spector, I heard two or three irregular bounces on my landladys door; and at the opening of it, a loud cheerful voice inquiring whether the philosopher was at home. I immediately recollected that it was my good friend Sir Roger’s voice, and I had promised to go with him on the water to Spring Garden, in case it proved a good evening. We were sooner come to the Temple Stairs, but we were surrounded by the crowd of having seated himself, and trimmed the boat with his coachman, who, being a very sober man, always serves as ballast on these occasions, we made the best of our way to Fauxhall. We were now arrived at Spring Garden, which is exquisitely pleasant at this time of year. When I considered the fragrancy of the walks and bowers, with the choir of birds that sung upon trees, and the loose tribe of people that walked under their shades. I could not but look upon the place as kind of Mahometan paradise. Sir Roger told me it put him in mind of a little coppice by his house in the country, which his chaplain used to call an aviary of nightingales.

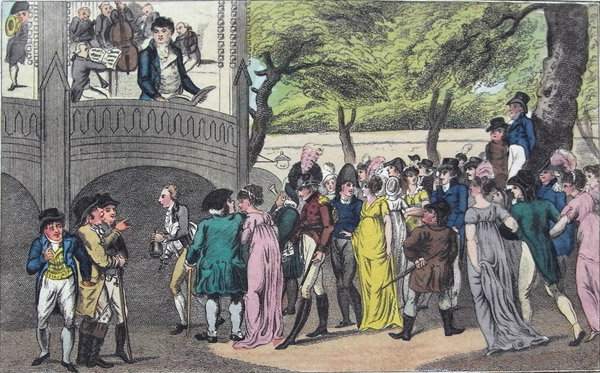

Syncopated pick-pocketry: this picture, from David Coke and Alan Borg’s Vauxhall Gardens: A History (Yale, 2011) is the headpiece to a song called ‘One Half of the World Don’t Know How t’Other Lives,’ which the popular tenor Charles Dignum performed at Vauxhall Gardens. The print, published by Laurie & Whittle in 1805, neatly represents the mixed audience for music at Vauxhall Gardens. There’s Mr Dignum singing in the famous bandstand (called ‘The Orchestra’), and so as far as the authors know, this also the only representation of a constant problem to the Vauxhall Gardens proprietors – a pickpocket at work in the crowd (see the group of three people, lower left). The print in itself may be a little light-fingered in that it is loosely based on a celebrated 1784 Rowlandson print of Vauxhall Gardens.

While musing there, “a mask who came behind him gave him a gentle tap on the shoulder, and asked him if he would drink a bottle of mead with her, but the knife, being startled at so unexpected a familiarity told her she was a wanton baggage, and bid her go about her business. We concluded our walk with a glass of Burton ale and a slice of hung beef. As we were going out of the garden, my old friend, thinking himself obliged, as a member of the quorum, to animadvert upon the morals of the place, told the, mistress of the house, who sat were more nightingales and fewer strumpets.

In 1728 Elizabeth Masters granted a lease of the 12 acres of the Spring Garden to Jonathan Tyres, of ‘Denbies’, Dorking, Surrey, for 30 years at £250 per annum. William Hogarth, the painter, who had recently married, moved to lodgings in South Lambeth in the following year and met Tyers. Together they devised the spectacular re-opening of the Garden – the Ridotto al fresco-on the evening of Wednesday 7 June 1732. The doors were opened at 9.00pm and tickets were one guinea each. A report in the press of the time stated that

The Daily Advertiser of 21 June 1732 gives a somewhat different account:

After the first night, the admission charge was reduced to one shilling per person and season tickets in the form silver or bronze medallions were issued. Hogarth, who was responsible for the design of the medallions, was given a life ticket in gold to admit ‘a coachful’ and bearing the inscription ‘in perpetuam beneficii memoria’.

The Prince of Wales who, as Duke of Cornwall, was Lord of the Manor of Kennington in which the Garden was situated, became an enthusiastic patron and frequent visitor to the Garden. On 6 July 1735, just a month after the opening of the covered orchestra loggia, he went to Vauxhall by water from his house at Kew. In the following year, a newspaper report of 16 August records that

By the mid- 1730s the layout of the Garden, including the broad tree-lined avenues was well established. The raised Orchestra building was central feature, enhanced by the installation of an organ in 1737. The 1738 season opened on 26 April with the issue of one thousand tickets at twenty-four shillings a piece-each ticket containing silver to the value of three shillings and sixpence. The same year saw the erection of a life-size statue of the composer, George Fredrick Handel, executed by Louis Francois Roubiliac at a reputed cost of three hundred pounds. This is believed to be the first recorded instance of a statue being erected to a living celebrity.The establishment, by Hagarth Francois Gravelot brought together a talented group of students included the young Gainsborough, a number of whom carried out paintings for the decoration of the ‘supper boxes’ at Vauxhall. A number of these were executed by Francis Hayman, a theatrical scenic artist, who worked from designs by Hogarth.

1743 saw the erection of the rotunda or ‘umbrella room’, designed by George Michael Mose, and executed in stucco-work by French and Italian craftsmen. Then had a diameter of some seventy feet and is described in a contemporary account as ‘..an edifice framed in the highest delicacy of taste’. The ceiling was adorned with painted festoons of flowers terminating in a point, and resembled the dome of an august royal tent. The roof was contrived so that ‘sounds never vibrate under it; by which means, music is heard to the greatest advantage’. There were 16 sash windows, each framed with elegant carving, and crowned by a plume of feathers-the crest of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales-as were the frames of the 16 oval looking-glasses which interspersed them so that a spectator standing in the centre of the rotunda might see himself reflected in each. Under the windows, set on brackets between twin white vases, were sixteen fine white busts portraying eminent personages, ancient and modern. In the centre hung the magnificent chandelier, eleven feet in diameter, with three rows of arms carrying a total of seventy-two candles. The inside of the doorway was framed by a rail supporting wax candles held by artificial roses.1745 saw the introduction of vocal music with performances by Mrs Arne, wife of the resident composer Dr Thomas Arne. By 1748 the charge for a season ticket for two persons had risen to two pounds. One of the most popular events ever to take place at Vauxhall Gardens was the rehearsal for Handels ‘Music for the Royal Fireworks’ on 21st April 1749. Although the rehearsal was without the fireworks, around one hundred musicians were employed and the spectators are reported to have numbered some twelve thousand . The following year 1750, saw the opening of Westminster Bridge and as the new Kennington Road was not yet built, Tyers purchased and demolished a number of old houses in Red Lion Yard, opposite Lambeth Church in order to provide access to a coach-way to Vauxhall. Such was the novelty of visiting the gardens by coach that on the first night the coaches reached all the way from Vauxhall to beyond Lambeth Church, a distance of nearly a mile.In 1751 the Gardens’ great patron, Fredrick Prince of Wales, died, to be succeeded by Prince George, later to become King George III. It was feared at the time that this event would have lessened public enthusiasm for the Gardens, but this does not appear in any way to have interrupted it. The orchestra building was rebuilt it 1757 ‘in ‘Moorish’ Gothic style, and in the following year Tyres became the sole proprietor of the Gardens.The Dark walks at Vauxhall acquired come notoriety during the latter pert of the eighteenth century, and in 1763 they were closed by order of the magistrates, though they were reopened in the following year after lighting was provided. In 1767 Jonathan Tyers died and ownership of the Gardens passed to his sons, Thomas and Jonathon. A further ‘Ridotto Al Fresco’ was held on 10th June 1769 attended by some ten thousand visitors. For this event a covered collonade was erected in the Grove and the whole garden was illuminated by around five thousand lamps. Music continued to play an important role in the programme of entertainment’s provided at Vauxhall and many well-known singers and musicians were engaged to perform there. The singer, Mrs Weichsell, was a frequent performer and James Hook was appointed as organist in 1774.

The behaviour of those frequenting the gardens was not always what might have been wished and in 1773 The Vauxhall Affray attracted much adverse publicity whilst in the following year, it is recounted that on 4th September ‘fifteen foolish bucks were detained for breaking lamps and causing other damage. There was no police force patrolling the Gardens at this time, but order was maintained by a detachment of soldiers. A constant topic of conversation was the exorbitant cost and the diminutive portions of the refreshments provided there and the sliced ham was particularly notorious. In one account it was claimed that a newspaper could be read through a slice of Tyers’ ham or beef, and it is reputed that a certain carver was employed on his promise to cut a ham so thin that the slices would cover the whole garden like a carpet of red white. A Report, ‘in The Connoisseur of 1775, describes a family visit to the Gardens and the father, they are half-a-crown a piece and no bigger than a sparrow.’ At which his wife retorted. ‘You are so stingy, Mr Rose, there is no bearing you. When one is out a party of pleasure, I love to appear somebody, and what signifies a few shillings one in a way, when a body is about it?’ Encouraged by their mother, the young ladies asked for ham also upon its arrival their father lifted a slice on his fork and pronounced: A shillingsworth here weighs an ounce-that is sixteen shillings for a pound-a reasonable profit, surely. If ham weighs thirty pounds, why your master makes twenty-four pounds on every ham, and if he buys the best and salts them himself they cost him ten shillings apiece.

Visits by celebrities and members if the aristocracy played an important part in the social life at Vauxhall: the presence of the Duke and Duchess of Camberland on 25th June 1781 attracted some eleven thousand visitors and 1784 saw a celebration of the 100th anniversary of the birth of George Fredrick Handel. Rowlandsons well-known drawings of the Gardens at around this time shows how many famous personalities of the period, including Dr Johnson, James Boswell and Mrs Thrale, The Prince of Wales and the Duchess of leader of the orchestra, James Hook the organist, and a number, of the other players. In 1785, Tom Tyers sold his interest in the Gardens to his brother, Jonathan, who became manager. The 1786 season saw a Jubilee Ridotto to celebrate the twenty-fifth year of the reign of King George III, for which a further fourteen thousand lamps were provided to enhance the illuminations. A supper-room was added, to the left of the rotunda, and Handels statue repositioned at the rear of the Orchestra.

On the death of the younger Jonathan Tyers in 1792 ownership of the Gardens passed to Bryan Barret, High Sherrif of Surrey, who was married to Tyers daughter Elizabeth. A Masked Ball was held on 31 May contemporary accounts describing the Gardens as a Blaze of Light. Admission charges were raised to two shillings, or three shillings on Gala nights. Toward the end of the century new forms of entertainment were introduced, with fireworks first exhibited in 1798 and Balloon ascents, by M. Garnerin and his two companions, in 1802. In 1809 ownership passed to George and Jonathan Barratt and during the following years many of the fine trees were cut down to permit the building of a collonade. A banquet was held at the Gardens on 20 June 1813 in celebration of the victories of the Duke of Wellington. Vauxhall Bridge opened in 1816, providing more convenient access to the Gardens and it was in the year that the tightrope walker, Mme Saqui, was engaged to perform at a fee of one hundred guineas per weak.

The Barrett family, sold their interest in the Gardens in 1821 to Messers T. Bish, F. Gye, and R.Hughes for a reputed figure of £30,000, and on 3 June the following year they re-opened, by permission of King George IV, as The Royal Gardens, Vauxhall. Although the admission charge was then raised to three shillings and sixpence it is recorded that 133,279 visitors were admitted during the 1823 season and 120,00 in the 1826 season when the charge persons paying for admission on any one night that year was 20,137 though this was probably later exceeded when the Gardens were opened free of charge on the occasion of the Coronation of William IV. Spectacular displays were popular and re-enactment of the Battle of Waterloo with fireworks and one thousand horses and foot soldiers were major attraction in 1827. 1883 saw a decline in the quality of the clientele and on 2 August a one shilling night attracted 27,000 visitors. Later on 19 August, a benefit night was held in honour of Mr Simpson who had acted as Master of Ceremonies for 36 years, a central feature being a fortified effigy of Simpson executed in coloured lights.

The balloonist, Charles Green, made an ascent from the Gardens in 1835, remaining airborn for the duration of the night. In the following year, on the afternoon of 7 November, he lifted off in company with Messrs Monk and Holland in a giant balloon, later named Nassau, which descended at Coblenz the following morning, a distance of nearly 500 miles having being covered in 18 hours.

In July 1837 Mr Green and the Nassau were involved in an unfortunate experiment which resulted in the death of Mr Cocking who had planned to descend from the balloon by means of a parachute suspended some 40 feet below it, watched by a vast crowd at the band of the Surrey Yeomenry played the National Anthem. Mr Gye, the proprietor of the Gardens, had tried to dissuade Mr Cocking from the experiment but Mr Cocking had wind and the parachute held the balloon steady as it rose perpendicularly for about ten minutes before being obscured by cloud. Mr Green said he had asked to ascend to 8,000 feet but had not been able to rise beyond 5,000, as it was difficult to throw out ballast without it falling into the parachute. The effect of the parachute detaching itself from the balloon had caused the balloon to rise suddenly to a height of nearly five miles during which ascent Mr Green and his companion, Mr Spencer, were almost overcome by only by the use of tubes connected to a bag containing air that they managed to survive, and the Nassau eventually landed close to the village of Offham, near Malling, in Kent.

In 1840 the Gardens closed but they re-opened in July 1841. Mr Alfred Bunn, the stage manager, published a periodical pamphlet entitled Vauxhall Papers with anecdotes about the Gardens which appeared three times a week at sixpence a copy, but this folded on 23 August after only 16 issues. The Gardens again closed on 8 September and the following day they were auctioned for £20,000, though the furniture and fittings were sold, including a couple of dozen painting by Hayman at around 30 shillings a piece.

The Gardens re-opened yet again in 1845 with twelve MCs and 40,000 lamps and the following year the oil lamps were replaced by gas lightening. 1947 saw the spectacle of A view of Venice with imitation water and a Grand Venetian Carnival was held in 1849 with 60,000 lamps. There were further balloon ascents, but the building of the railway viaduct from Nine Elms Waterloo, cutting the Gardens off from the river and smothering them with a pall of black smoke, together with the rival attractions of the Crystal Palace at Sydnham Hill eventually brought about the demise of one of Londons most enduring places of entertainment after more than two hundred years. The final ‘Last Night’ was on the 25th July 1859, following which the site and its contents were sold by auction on August 22nd , realising the sum of £800. The building of St Peter’s Church commenced in 1863 and it was consecrated the following year. The adjoining vicarage, St Peter’s House at 308 Kennington Lane, is the only remaining structure to survive from the time when the Gardens flourished.

Bibliography

ALLAN, Mea The Tradescants (1964)

ALLEN, T. History and Antiquities of the Parish of Lambeth (1827)

BOULTON, William The Amusements of Old London (1901)

BUNN, Alfred (ed) Vauxhall Papers (1841)

COKE, David The Muses Bower (1978)

DIRCKS Life of The Marquess of Worchester (1863)

DUCAREL, A. C. History and Antiques of the Archiepiscopal Palace of Lambeth (1785)

GARDINER, D.The story of Lambeth Palace (1930)

GODFREY, W. H. (ed) London Topographical Record Vol XIV (1928)

HILL, G. The Electoral History of the Borough of Lambeth (1879) HODGKINSON, T. Handel at Vauxhall (1969)

LEITH-ROSS, P. The John Tradescants, Gardeners to the Rose and Lily Queen (1984)

LONDON COUNTY COUNCIL, Survey of London, Vols XXIII & XXVI (1950-51) LYSONS, D. Environs of London (1799-1806)

MANNING & BRAY County History of Surrey (1814)

MONTGOMERY, H. H. History of Kennington and its Neighbourhood (1889)

NASH, A.D. Living in Lambeth, 1086-1915 (1951)

NICHOLS, J. History and Antiques of Lambeth (1786)

RAWLINGS, A. G. The Parish Church of St Mary-Virgin, Lambeth

SCOTT, W. S. Green Retreats: The Story of Vauxhall Gardens 1661-1859

SOUTHWORTH, J. G Vauxhall Gardens (1941)

TANSWELL, J. History and Antiques of Lambeth (1858)

WALFORD, E. Old and New London, VOL VI

WROTH, W. London Pleasure Gardens 1896