By Olga and Michael Leapman

A story as striking and incidents as strange as ever have occurred in the most startling fiction.

‘The Times’, July 1862

Murder is often seen as the quintessential Victorian crime and scores of books have been written about the most notorious killers of the age – Jack the Ripper, Wainewright the Poisoner, William Palmer to name a few. Fraud is an altogether more complex offence, as Michael and the late Olga Leapman argue in this hitherto unpublished paper. The outline for a book that was never written, it is based entirely on research by Olga, who died in 2019.

The sunny Saturday morning of 31 March 1857 was one that William Roupell would remember ruefully throughout his long and painful life. Shortly before 11am he drove in a long procession of horse-drawn carriages to the hustings – a wooden platform erected near the north entrance to Kennington Common in south London for the purpose of the Parliamentary election. He and his supporters had gone to hear the declaration for the two House of Commons seats for Lambeth. There were three candidates, all Liberals: the two who had previously held the seats and Roupell, at 25 making his first bid to enter public life.

The returning officer, Mr Onslow, stepped on the platform to announce the result. The number of qualified electors in Lambeth – this was before the introduction of universal male suffrage – was just 20,276. Each was allowed two votes, and about half of them turned out. Roupell had come top of the poll with a remarkable 9,318 votes, meaning that some 90 per cent of those voting had made him one of their two choices. William Williams won 7,648 and a bitter William Wilkinson (who had topped the poll at the previous election) lost his seat, with only 3,234.

Roupell was triumphant. In an excited address to the electors he claimed – none too convincingly – that he was not “puffed up” by his success and would try to fulfil his new responsibilities. He described his overwhelmingly victory as ‘a triumph of liberty and truth over the modern system of timeserving and hypocrisy’.

Hypocrisy? William Roupell, who on that memorable March day seemed on the threshold of a glittering political career, sure knew a thing or two about hypocrisy. For by the time he stood on those hustings he had already embarked irrevocably on a career of deceit that was to turn all his promise, all his hopes and ambitions, to ashes.

***

You will not come across Roupell Street unless you are looking for it. Concealed among a maze of back streets only a few hundred yards from Waterloo Station, Roupell Street comprises what Bridget Cherry, in The Buildings of England, has described as ‘very modest early nineteenth-century workers’ terraces’. Modest maybe, but their proximity to central London, combined with a surprisingly secluded aspect, has today transformed them into desirable town houses for the professional middle class, including some Members of Parliament. What these upscale residents may not know is that their bijou and appealing little street played a central role in a sensational political and financial scandal that transfixed mid-Victorian London.

The houses were built by John Roupell, a wealthy iron smelter and property owner from Peckham, south-east London. The estate was to be passed on to his son Richard who in 1815, in his early thirties, began a liaison with Sarah Crane, a carpenter’s daughter aged just seventeen. They cohabited (at least at weekends) but John disapproved of Sarah and would have disinherited Richard had they married. That did not deter them from having four children out of wedlock – John, born in 1826, William in 1831, Sarah in 1834 and Emma in 1837. Richard’s father died in 1835 and eventually, in 1838, Richard married Sarah, the mother of his children. They had one more son after that, in 1840 – and to celebrate his being their only legitimate heir they named him after Richard. The stage was now set for a tragedy that would leave the family in despair, its reputation in tatters.

Richard senior was a bad father. Although he kept his wife and children in comfortable circumstances in a large house in Streatham, he continued to stay five nights a week in a smaller house in Cross Street, off Blackfriars Road. An autocrat who brooked no argument, he quarrelled violently with his eldest son, John, who went abroad in 1851 and did not return. His second son, William – the central character in this melodrama – was superficially more amenable, though ambitious from an early age.

After leaving school, William worked as a rent collector for his father, and continued to do so when he began legal studies in the Inner Temple at the age of 18. Eager to become a man of substance, even to enter public life, he involved himself in business dealings with his uncle Frederick Watts, his mother’s brother-in-law. It was an era of frenzied financial speculation, with fortunes being made and lost in the City on volatile stocks in the new railway companies and other tempting but unreliable securities. Either through deception or mischance, William’s deals went wrong and he soon ran up considerable debts.

By 1855 his position was so serious that he crossed a fatal chasm: he began, casually at first, to dabble in fraud. Working for his father, it was quite easy for him to gain access to the deeds of the family properties, so he knew how official documents were worded and what they looked like. From there, it was a short step to forging deeds of gift that would name him as the owner of various of his father’s properties and allow him to raise money on them. In this way his debts were soon paid and he began to live the life of a well-heeled bachelor.

Richard Roupell senior died in September 1856 in the Cross Street house. William and his mother visited him on his deathbed. While his mother stayed downstairs, William went to the first floor office to search his father’s bureau and found a will leaving most of the family fortune and property to Richard – his youngest but only legitimate son, then a schoolboy of sixteen. This was not the only problem with the will from William’s point of view. More threateningly, if it were allowed to stand it would bring to light the forged deeds by which he had raised money on property that was now legally part of Richard’s inheritance. So he concealed the real will and, over the next few days, forged a new one – in the form of a codicil dated a few days before his father’s death – in which all the estate was left to his mother, with she and William acting as executors. He then persuaded his mother to waive her rights as executor, leaving him to dispose as he wished of the entire inheritance, valued at some £300,000.

His frauds had transformed William into a young man of great wealth and supreme confidence, not to say hubris. Still only 25, he became a well-known dandy at the Inns of Court, striding about in a distinctive suit of white drill (heavy cotton), with matching hat and boots. He appeared to believe that his criminal acts could forever stay concealed, and decided that it was time to taste the fruits of public life. In 1857, less than a year after his father’s death, he ran for Parliament for the Lambeth constituency, as a Whig reformer.

William used his stolen riches to spend lavishly on the campaign and he came top of the poll, while his party, led by Lord Palmerston, enjoyed a comfortable majority. The defeated candidate instituted an action alleging that William had bribed voters, but it was dismissed. He took rooms in St James’s Square and was a familiar figure at salons and society functions. He served on several parliamentary committees, although he spoke in the chamber infrequently. He remained popular in Lambeth and was re-elected in 1859. Now his political future seemed assured, and to cement his local reputation, he contributed generously to raising a volunteer regiment, the First Surrey Rifles. As a reward for this selfless work he was invited to meet Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace. Surely nothing now could hamper his elevation to high office?

On 3 February 1862, at the Horns Tavern in Kennington, William delivered his annual ‘account of stewardship’ to a crowded gathering of his constituents. He coolly listed the achievements of Lord Palmerston’s administration – including the abolition of duty on newspapers, plans to embank the Thames, the removal of the tolls on the Dover Road – and regretted that there had been no progress on two of his other favourite causes, the secret ballot and reform of the Bankruptcy Act. He ended by expressing sorrow at the recent death of Albert, the Prince Consort. The MP was loudly cheered, as always, and a resolution of support was carried unanimously.

***

Seven weeks later, on 30 March 1862, William Roupell fled to Spain and began the procedure for resigning his seat in Parliament.

The trigger for his abrupt departure was that his brother Richard, now over 21, had apparently discovered his frauds and was starting legal proceedings to reclaim the properties that were rightly his. By now William had sold most of them to innocent third parties who had no idea that he was not the legal owner, but who now faced having to forfeit the properties to Richard. The first case, concerning the Norbiton Park estate in Surrey, was to be heard at Guildford Assizes on 18 August 1862, and some of the most eminent counsel in the land had been retained by both sides.

A few days before the trial was due to begin, a sensational, scarcely credible report circulated that William had returned to London and would be giving evidence at the trial, in which he would confess to his forgeries. He had been spotted walking in Richmond with Annette Haslam, the wife of the solicitor to whom he had been articled.

Just why he left a place of safety (Spain had no extradition treaty with Britain) to face inevitable prosecution remains a mystery. He claimed he had finally ‘been awakened to the enormity of my sin’. More likely – and there were hints of this later in the mysterious letters to the newspapers from his acquaintances – he had been threatened with blackmail by somebody close to him who knew of his forgeries. Suspicion focuses on Frederick Watts, his mother’s brother-in-law and the early business partner in whose ventures William had lost so much money. Was it Watts, then, who finally betrayed William to Richard?

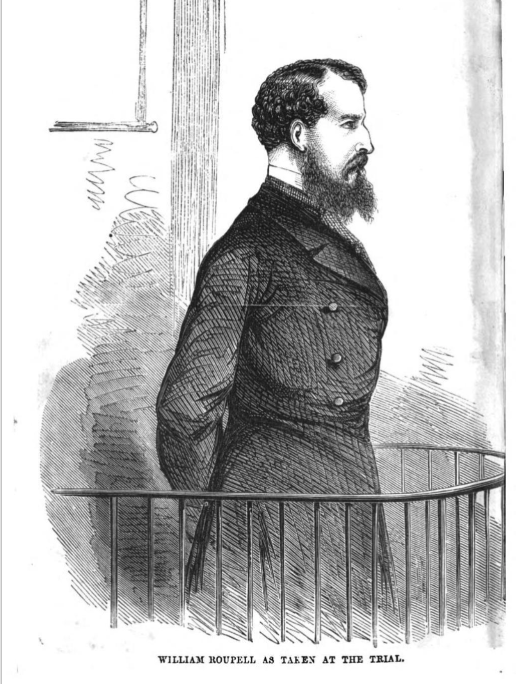

At the trial, which attracted enormous interest from the press and public, another theory was put forward by counsel for Mr Waite, the unfortunate man who had bought the property from William and now faced having to forfeit it to Richard. The lawyer argued that William had not in fact forged any deeds, but was claiming to have done so to enable his younger brother to claim property that had been legitimately sold.

After two days there was an out-of-court settlement. Mr Waite was allowed to keep title to the estate after paying Richard Roupell £8,000 – about half its value. Other cases involving people who had bought property from William were later settled on the same basis. The Guildford judge ordered William’s immediate arrest on charges of forgery and perjury. He was taken to Horsemonger Lane Prison in Southwark, and then to Newgate Prison, to await trial. Nobody from his family visited him in gaol, but Mrs Haslam did.

At his trial at the Old Bailey on 24 September 1862, William pleaded guilty. In a long personal statement he claimed that the first fraud had been perpetrated to repay a favour for a close acquaintance who had previously lent him money to buy books for his legal studies. This was again believed to refer to Watts, who had by now fled the country, never to return. William denied that he had been a libertine or a gambler, as press reports had suggested. He was sentenced to penal servitude for life.

In the normal course of events William would have been transported to the colonies to serve his sentence, but he avoided that because his presence might always have been required in court for further civil litigation. The longest trial was at Chelmsford in July 1863, concerning the Great Warley estate near Brentford in Essex. It lasted eight days and received massive publicity. Several handwriting experts were called as witnesses. The identification of handwriting was a new and developing science – Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had Sherlock Holmes dabbling in it a few years later – and the experts disagreed on whether William had forged his father’s signature on the will and the deed of gift.

At the end of the trial the jury, after long deliberations, failed to agree a verdict. The mysteries surrounding the case remained. These are

- Was Watts truly the villain of the piece (Mrs Watts gave evidence in her husband’s absence, but was often scarcely coherent.)

- Why did William return voluntarily from Spain?

- Did he really forge the documents, or was he conspiring with his brother to reacquire the properties he had legitimately sold, as some lawyers were still asserting?

- What was his relationship with Annette Haslam, and what role did she play in the affair?

From then on, although there were rumours of further trials in the offing, all disputes were settled out of court. William remained in prison, mostly at Portland, where he was called ‘the good convict’, and on one occasion helped to entrap a corrupt warder who persuaded prisoners to get their relatives to send him money in return for favourable treatment. He worked for some years in the prison hospital, helping and comforting the sick. He was released on 22 September 1876, after serving 14 years of his sentence.

He went back to live with his mother and sister Sarah in the old family house in Streatham. The local vicar, anxious that he should be welcomed back into the community, walked round the parish arm in arm with him. When their mother died in 1878, aged 81, he and Sarah moved into a smaller house nearby.

His political ambitions clearly at an end, William Roupell spent the rest of his life as a poor but apparently honest bachelor and devout churchman, highly regarded by the community. A keen gardener, especially interested in growing fruit, he became a founder and president of the Streatham and Brixton Horticultural Society.

His brother Richard, who had by now settled all the outstanding legal cases, moved out of the family home as soon as William was released from prison. Richard died in 1883, aged 42 and unmarried. His estate was valued at £13,225, nearly half of which was left to Mrs Linklater, the wife of his solicitor. The family house, which he still owned, was left to his mother. He left William an annuity of £52, to be paid at £1 a week. His sister received an annuity of £200 until she died in 1894, aged 60. Her estate, valued at £126, was bequeathed to William, who died in March 1909 at the age of 77. Two hundred people attended his funeral at West Norwood cemetery.

For more on the Roupells and shady 19th-century property goings-on, see Judy Harris’s The Roupells of Lambeth: Politics, Property and Peculation in Victorian London (Streatham Society, 2001, £6.40 including p&p).