By David Coke

In 2019 I attended a lecture intriguingly entitled ‘The Shows and Sights of Georgian London – a Board Game tour of the Metropolis’ by Professor Adrian Seville at the Society of Antiquaries in Burlington House. Professor Seville is a leading authority on English board games and has created what must be the finest collection of historic board games in the UK, so the talk promised to be interesting and wide-ranging.[1]Visit Adrian Seville’s website www.giochidelloca.it for his database of 2,500 examples of antique board games.

I had heard a rumour that Vauxhall Gardens, the great pleasure garden of Georgian London, made an appearance on children’s board games in the 19th century, so I was planning to ask the speaker whether he had come across this in his collecting. But the lecturer soon pre-empted my question, and Vauxhall Gardens turned up with some regularity throughout his talk, much to my surprise. Vauxhall was the only one of the pleasure gardens to occur in this context, but it did occur, and frequently.

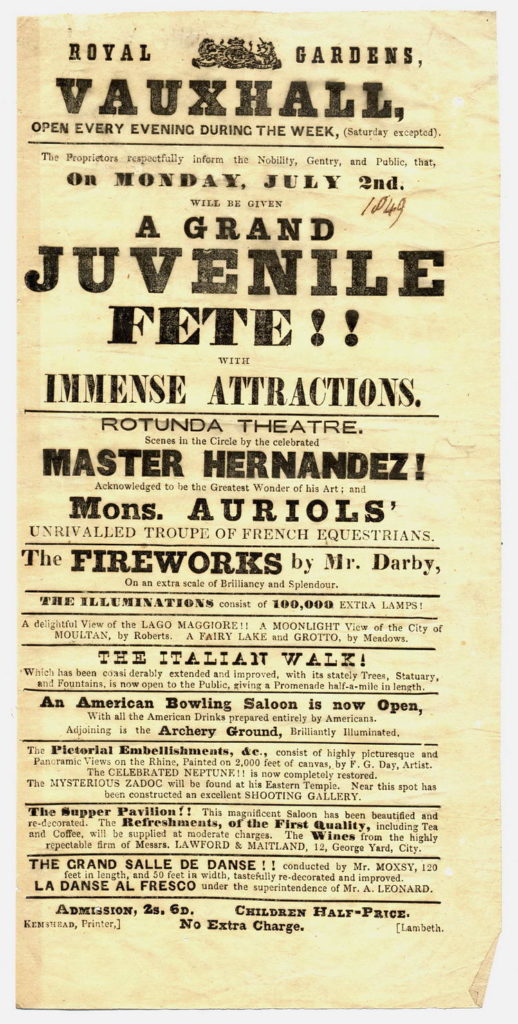

It is clear that Vauxhall Gardens, which did not close until 1859, was so familiar to everybody that its use in this context was unremarkable. Its commonly-held reputation today as a notorious place of low morals was, in the early 19th century, sufficiently forgotten to allow its uncontroversial inclusion in a game for children. The closely-crafted atmosphere of Vauxhall Gardens at that time, as, indeed throughout its life as a pleasure garden, was one of what American theme park designers would later call ‘safe danger’. Children were taken to Vauxhall by their parents throughout its history, and in the 19th century some of its most successful events were to be the so-called Juvenile Fetes, introduced for a younger audience by the new lessees, Frederick Gye and Thomas Bish, in 1821, and held regularly thereafter.

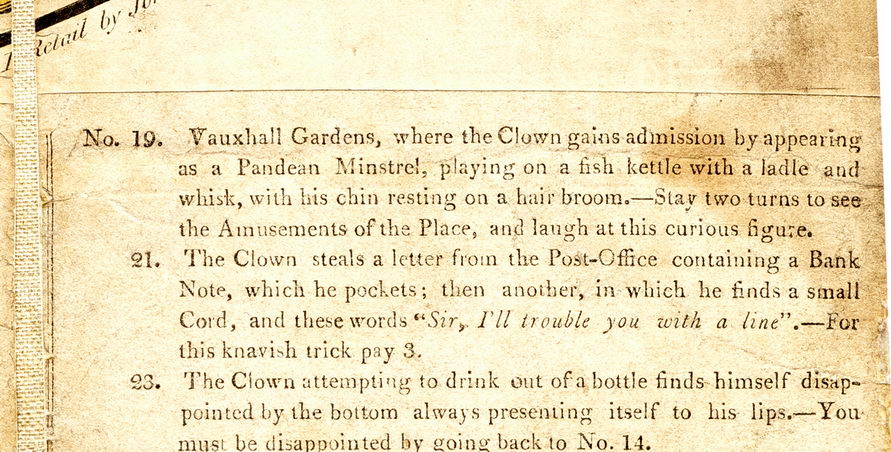

Early board games, marketed for this same audience, were printed on paper supported on a linen base and often folded for storage into a pouch or slip-case, much like road maps of the 20th century. They were usually ‘race’ games, in which the winner was the first to land on the final square after surviving several set-backs. The 20th-century equivalent would be something like Snakes and Ladders, in which players can be made to go back, or pay forfeits, as well as forward, depending on where they land. Nineteenth-century games often included a long set of instructions, detailing what to do if a player landed on particular squares. More often than not, players would be keen to avoid the Vauxhall Gardens square on the board, because if you landed there you would have to spend two turns enjoying the entertainments, or else you would have your pocket picked and lose all your counters – ‘safe danger’ could hardly be better illustrated.

Race games formed part of a long tradition going back at least to the later 16th century, when the first printed games were published and sold. Although these games are known to have been printed since the 1580s, the earliest known printed board game in Britain, called The Game of the Goose, was first recorded on its entry at Stationers Hall in June 1597. Board games are always rare survivals because they were so well used by their young owners, and would be disposed of once they looked worn and dirty, to be replaced by something newer and more exciting.

Traditional dice were not normally used in playing these board games; this was because of their association with gambling, and also because of the consequent heavy taxation imposed on their sale. This prompted the reintroduction of a toy called a teetotum – a small spinning top that was often prescribed as a dice-substitute for use with children’s board games.

These teetotums could be hand-made at home, so were a useful tax-free substitute for dice. Some are very attractive small objects in their own right. In use, they are significantly quieter than dice, so may have recommended themselves to parents for that reason as well. Two 20th-century games continued to employ teetotums – one a cricket game called ‘Owzatt!’ and the other a gambling game called ‘Put-and-Take’, both of which I knew in my own childhood in the 1950s.

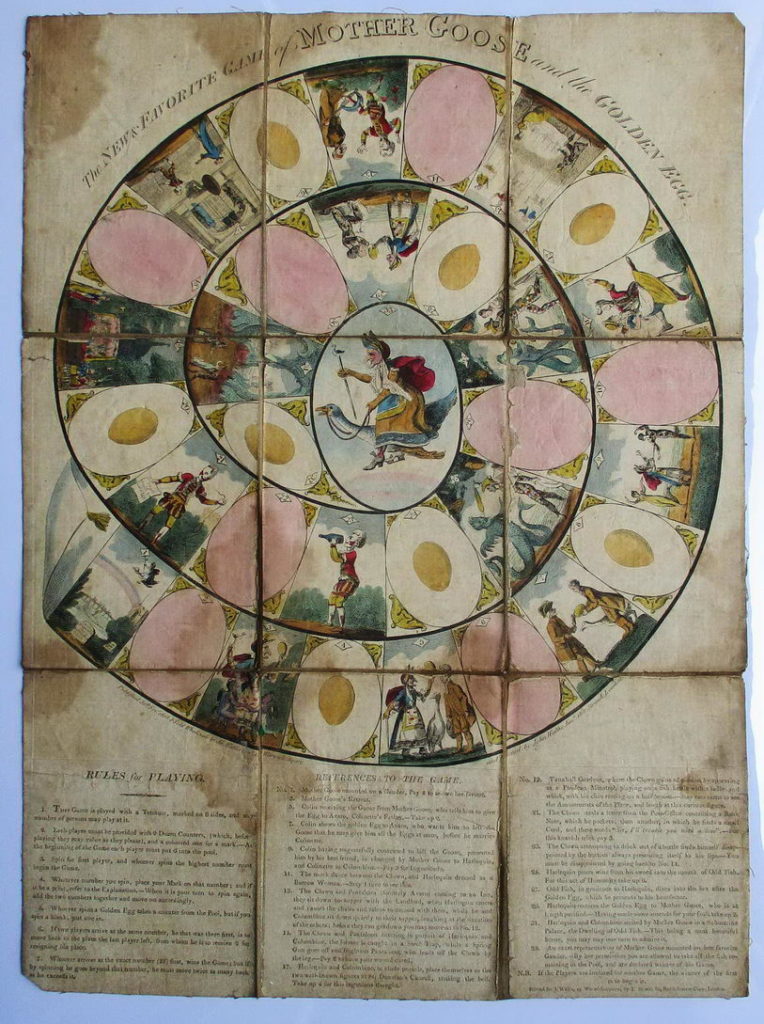

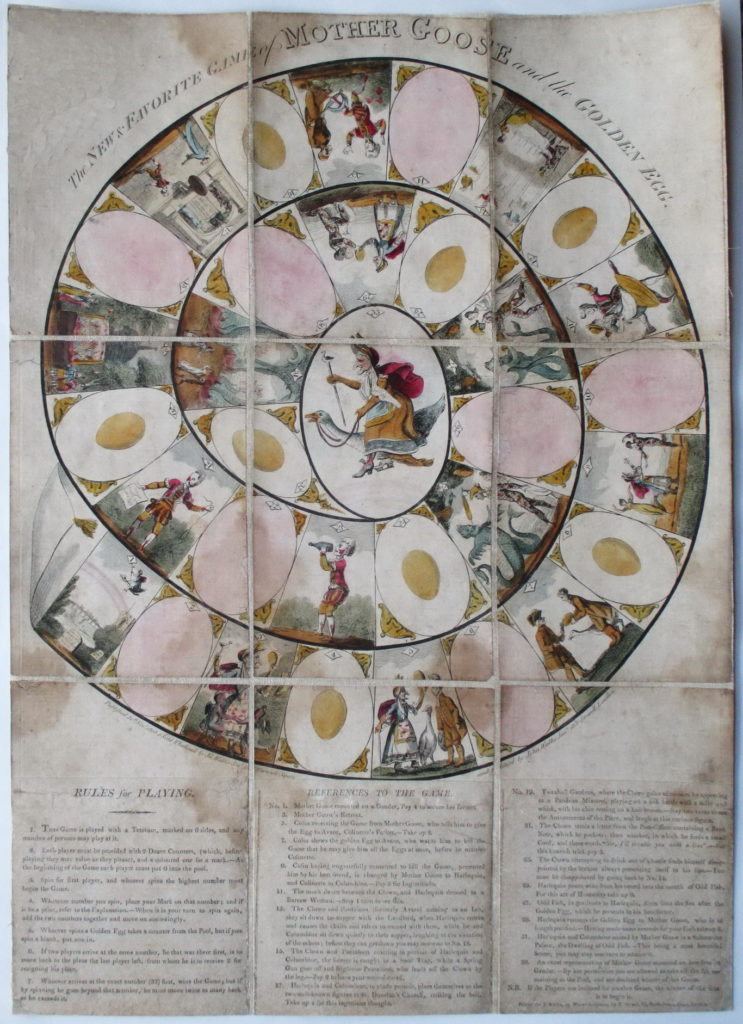

The earliest game mentioned in Professor Seville’s talk in which Vauxhall Gardens played a part was called ‘The New & Favorite Game of Mother Goose and the Golden Egg,’ first designed and published in 1808 by John Wallis Sr. of 13 Warwick Square, and retailed by his son John Wallis Jr. of 188 Strand, London. This was produced as a hand-coloured etching on paper backed onto linen and folded into a card pouch. A fine example of this game is in Professor Seville’s collection, and another, less well preserved, has recently entered my own Vauxhall Gardens collection from the dealership of Tony Mulholland in Sussex, whose catalogue notes have provided some of the description I have used in this essay.

The Game and its Source

The source for the idea behind this version of the game of Mother Goose is not hard to discover. In autumn 1806 the 35-year-old Thomas John Dibdin was approached by Thomas Harris, manager of the Covent Garden Theatre, to write a Christmas pantomime. Thomas Dibdin had been something of a theatrical jack-of-all-trades, having had some success as an actor, a singer, a songwriter, and even a scene-painter, but his strength lay in writing all sorts of theatrical productions, not least the production of pantomimes. Dismayed at the lack of time to prepare anything for Harris, Dibdin dusted off an old script that had been rejected by the same theatre five years earlier: Harlequin and Mother Goose, or The Golden Egg. The comedian and dancer Joseph Grimaldi (1778–1837) was to play the dual role of Squire Bugle and Clown, and other roles were, according to one source, ‘given to members of the Bologna family of acrobats’. This was the family of John Peter (or ‘Jack) Bologna (1775–1846), brought to England as a boy by his family who had formed a troupe of tumblers. Jack Bologna worked at some of the main London theatres, first at Sadler’s Wells in 1792 and later at Covent Garden, specialising in pantomime. There is meant to be a watercolour at the Museum of London by T.M. Grimshaw of one of the performances of ‘Mother Goose’ in 1808, with Jack Bologna as Colin/Harlequin, Miss Searle as Colinette/Columbine, Joseph Grimaldi as Squire Bugle/Clown, Louis Bologna as Avaro/Pantaloon and Samuel Simmons as Mother Goose; sadly I have been unable to trace this picture.[2]It is poorly reproduced in the ‘John Bologna’ entry in P.H. Highfill, K.A. Burnim and E.A Langhan’s A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers & other … Continue reading

Thomas Dibdin’s pantomime opened at Covent Garden Theatre on 26th December 1806,[3]Universal Magazine January 1807, p.62, which includes a rather sniffy criticism of the production, as beneath the critic’s serious notice, despite the audience’s rapturous response. directed by Charles Farley (who later directed the re-enactments of the Battle of Waterloo at Vauxhall Gardens); Mother Goose was preceded on stage by a version of George Lillo’s 1731 tragedy The London Merchant or the History of George Barnwell, a piece based on a popular ballad, in which an apprentice is seduced into an association with a vicious prostitute, leading to his eventual execution for theft and murder. This gloomy story left the audience hungry for something to amuse and entertain them, which is exactly what Dibdin and Grimaldi had come up with. After the pantomime’s opening scenes of illicit youthful love between Colin and Colinette, and Squire Bugle’s cruelty, Mother Goose, portrayed as a benevolent witch, transforms the characters into their pantomime personas; Grimaldi’s Squire Bugle becomes the ‘Clown’, while the young lovers are magically recast as Harlequin and Columbine.

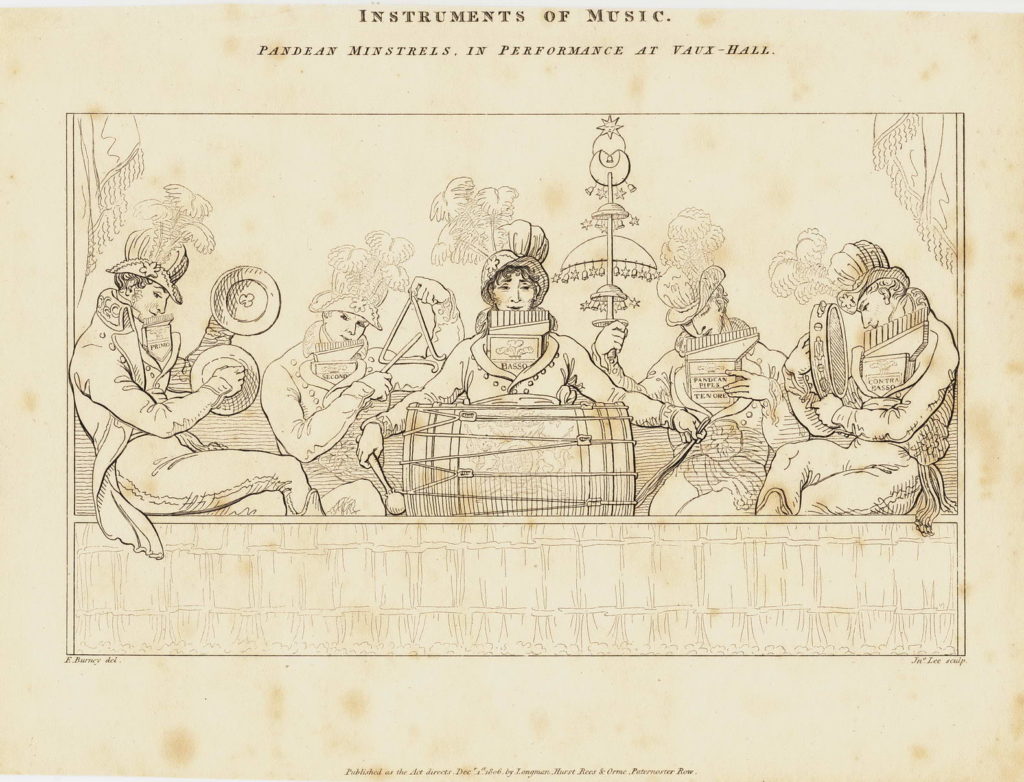

A series of scenes of slapstick violence plays out including an episode in Vauxhall Gardens; here, the Clown and Pantaloon manage to cheat their way in by disguising themselves as two of the so-called ‘Pandean Minstrels’, using various domestic utensils – a fish kettle with a ladle and whisk, and a household broom, as noted in the games instructions.

The Pandeans, who played different sizes of pan-pipes, and various percussion instruments, were a popular group of musicians from southern Europe. They first appeared at Vauxhall, dressed in exotic, quasi-military costume, in 1803, gaining huge popularity from the start, especially among female visitors, subsequently reappearing there every season for more than 20 years. The engraving of them by John Lee after E.F. Burney (1806) shows why the Clown chose the disguise he did, and why its success, under comic circumstances, might just have been credible, while the audience could all see through it.

Even though he was not happy with the pantomime himself (partly because of the amount of strenuous work it involved), Grimaldi had found in the Clown his most famous vehicle and he was, finally, after years of supporting roles, a ‘star’. The production ran for almost a hundred nights in 1806/7, making the Covent Garden proprietors the unprecedented profit of £20,000. ‘The New & Favorite Game of Mother Goose’, published as a board game two years later, commemorated one of the most remarkable events in London’s theatrical history, and it allowed families to recreate their memories of the pantomime in the comfort of their own homes. Other printed items of the time inspired by the pantomime, including illustrated writing sheets, proved equally popular.

Dibdin’s pantomime strongly recalled the long tradition of the Commedia dell’Arte, in which Harlequin and Columbine played regular parts, but it also prefigured later pantomimes based on fairy stories with fantastic and magical characters in mythical settings. Dibdin’s original work has been adapted and altered many times since it was first written; the story of Mother Goose has come down to us in many forms, often quite different from the pantomime. Perrault’s moralising fairy tales, translated into English in a publication of 1729, popularised the name, but the fame and spread of the story appear to derive almost entirely from the success of Dibdin’s pantomime, leading to the adoption of Mother Goose as a purely English figure.

Board Games

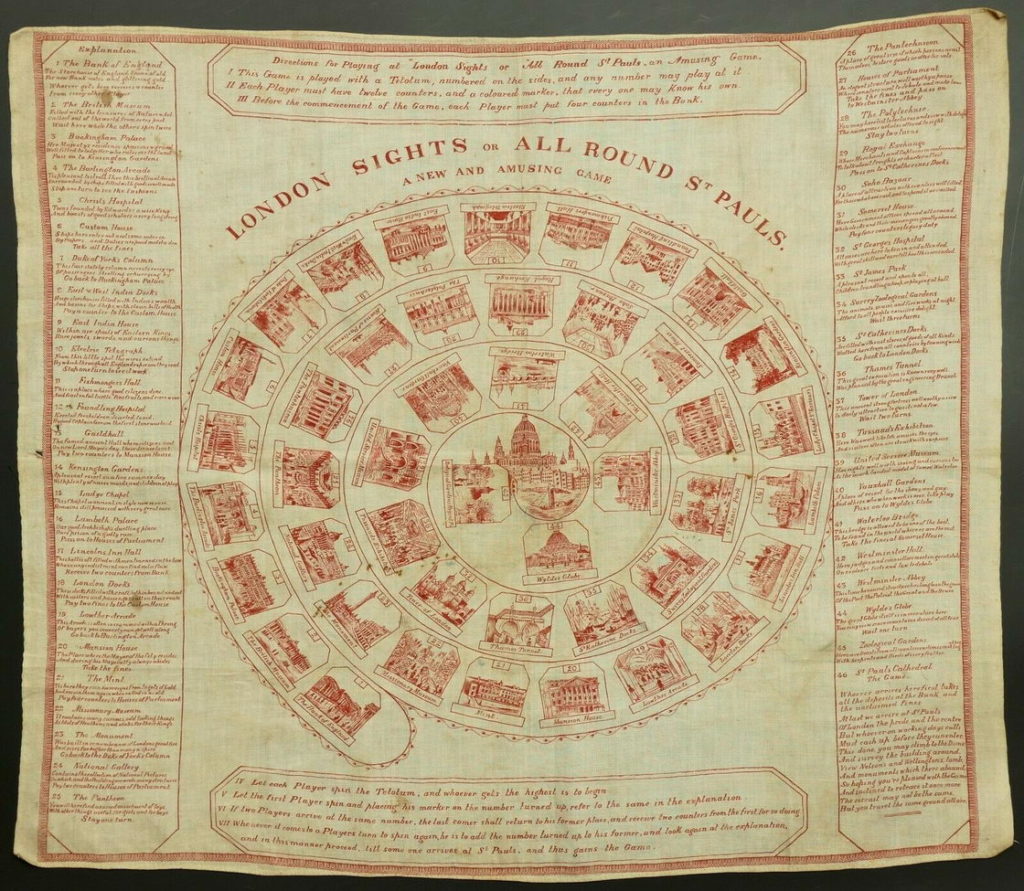

After the first of the really popular board games, others soon followed, several with London themes, and with names like ‘The Panorama of London’ (published by John Harris 1809). Square 30 is Vauxhall Gardens, where the player has to ‘pay [with some of his counters] to hear the music and singing.’ ‘The Survey of London’, by William Danton was published in 1820. This had several well-produced views of London sights, with moral captions to most illustrations. The game ‘Scenes in London’, published by Edward Wallis (younger son of John Wallis Sr.), in 1825, included the Cosmorama, the Monument, and the British Museum among several other sights. Square 16 is Vauxhall Gardens, where the player has his pocket picked, so losing all the counters he has left. The Vauxhall illustration shows a night-time crowd in front of the illuminated Orchestra, with glowing tableaux of moons, stars and festoons. ‘London Sights, or All Round St. Paul’s, a new and amusing game’ was printed on a cotton handkerchief, possibly as a souvenir for visitors to the Great Exhibition of 1851. A nice example of this has recently been acquired by the Foundling Museum in Brunswick Square, London because the 12th space shows the Foundling Hospital as one of the great tourist sights of London. Of course, Vauxhall is there too, as square no. 40.

This game, incidentally, is one of the few where to land on Vauxhall was actually a good thing, because you were instructed to move forward four squares to ‘Wylde’s Globe’, an attraction that ran only from 1851 until 1856, so giving a tight date bracket within which the undated game must have been produced.

Conservation

When the ‘New and Favorite Game of Mother Goose and the Golden Egg’ arrived in my collection, it was pretty fragile, stained with some unidentified brown splashes, and in a tired state generally. It had also, unsurprisingly, lost its original slip-case. However, it was otherwise remarkably complete, and its ‘Vauxhall Gardens’ square (the reason I acquired it) was clear and colourful, despite being split in two by one of the folds of the game. This uncommon survival was a good case for careful conservation treatment, but, because of its mixed materials and its fragility, it would need a real expert. Somebody I had worked with before was a paper conservator called Pamela Allen; Pam and her husband Stephen are both expert paper conservators, and Stephen has archive experience too, including book conservation and lining paper onto linen backings; Stephen also has previous experience of a similar board game of the same period, so their combined skills and long experience were invaluable. The game was passed to them in October 2019, and returned to me over three months later.

The conservation process raised several points of interest about this game which would not otherwise have come to light, and which may be otherwise unknown. First, running vertically through the first square of the game, the paper has an incomplete watermark ‘JOHN DICKINSON & CO. 1810’, showing that this impression of the game was printed at least two years after the plate was made, and on a paper of high quality. It is not known how many impressions of individual games would have been produced, or indeed how long they were produced for, but it would take several hundred sales to justify the initial outlay and production costs.

It soon became apparent to the conservators that the spiral of the game itself was printed (by the intaglio process) on different paper stock (the one with the watermark) to the letterpress instructions at the bottom of the game. The paper for the ‘game’ area is a ‘laid’ paper (showing the mesh marks of the manufacturing process) thinner and smoother than the letterpress ’instructions’ paper; it is also very strong; the instructions are printed on a slightly heavier hand-made ‘wove’ paper, with no watermark. The odd aspect of this is that it was normal practice for etchings and engravings (intaglio prints) to be printed on a soft, sized paper that could be moistened, and would easily collect the ink from the engraved lines. This means that the printer of the game area (Thomas Sorrell, of 86 Bartholomew Close, London) was highly skilled and took considerable time and effort over the project. It might also suggest that Dickinson’s new fine laid paper was not entirely suitable for the relief process of letterpress.

The 1810 date of the watermark corresponds to the time that Dickinson’s mill installed a state-of-the-art paper-making machine; the watermark itself is of a standard type for handmade paper, although it could easily have been incorporated into a machine-made product too. John Dickinson’s company, founded in 1804 in Hertfordshire, became a significant player in the stationery industry in England. By 1809, he had already patented a new process for making continuous sheets of paper at his Nash Mills in Apsley. Previously, only single sheets of limited size could be made, but Dickinson’s process began to produce extended lengths on his ‘endless web’ machine, in fact a revolving cylinder of mesh, onto which the pulp was drawn before being finished under a dandy-roller which also produced the watermark. Dickinson specialised in manufacturing fine and lightweight but robust paper. Because of its size, and its combination of thinness and strength, Dickinson’s paper would have been ideal for use in John Wallis’s new folding board game. What is obvious is that the production process which mounted the paper onto its linen backing must have been quite sophisticated, probably using new static steam presses. Linen and paper react quite differently to drying out from any wet-gluing process, which is likely to lead to the structure curling, as the conservators found when they tried to reinforce the paper sections after removal from the linen, even with very fine backings, before remounting them onto linen – a standard type of intervention for preserving old paper, but one that had to be abandoned in this case because, without the intervention of a steam-press, it was distorting the sections of the game. The original linen backing was not reused as a backing for the conserved paper sections, partly because it was too damaged at the edges and retained some of the contaminants that had damaged the paper surface, and partly because the original linen had been in two pieces roughly sewn together in the middle of the game area, putting unnecessary stress on the paper in that area; a full sheet of clean 19th-century linen was sourced by the Allens for the replacement, retaining the characteristic colour and texture of the original.

Stephen Allen the conservator said to me after the work was completed, ‘We have spent more time thinking and planning this conservation project than physically doing any work,’ but the work was certainly done, and the game is now very much more presentable, and, more importantly, is in the best possible condition to survive for another two centuries, so long as it can avoid being played on by children who spill their hot chocolate (or worse) over it.

All images, except where shown, are © David Coke.

References

| ↑1 | Visit Adrian Seville’s website www.giochidelloca.it for his database of 2,500 examples of antique board games. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | It is poorly reproduced in the ‘John Bologna’ entry in P.H. Highfill, K.A. Burnim and E.A Langhan’s A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers & other Stage Personnel in London 1660–1800, Carbondale & Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1973, vol.2 (of 16), p.190) |

| ↑3 | Universal Magazine January 1807, p.62, which includes a rather sniffy criticism of the production, as beneath the critic’s serious notice, despite the audience’s rapturous response. |