A new skyscraper – or two – thrusts itself up into the skies of Vauxhall-Nine Elms every year, it seems. It may be hard to imagine now, writes Andrew Rogers, but for the final third of the last century, the area’s skyline hardly changed at all.

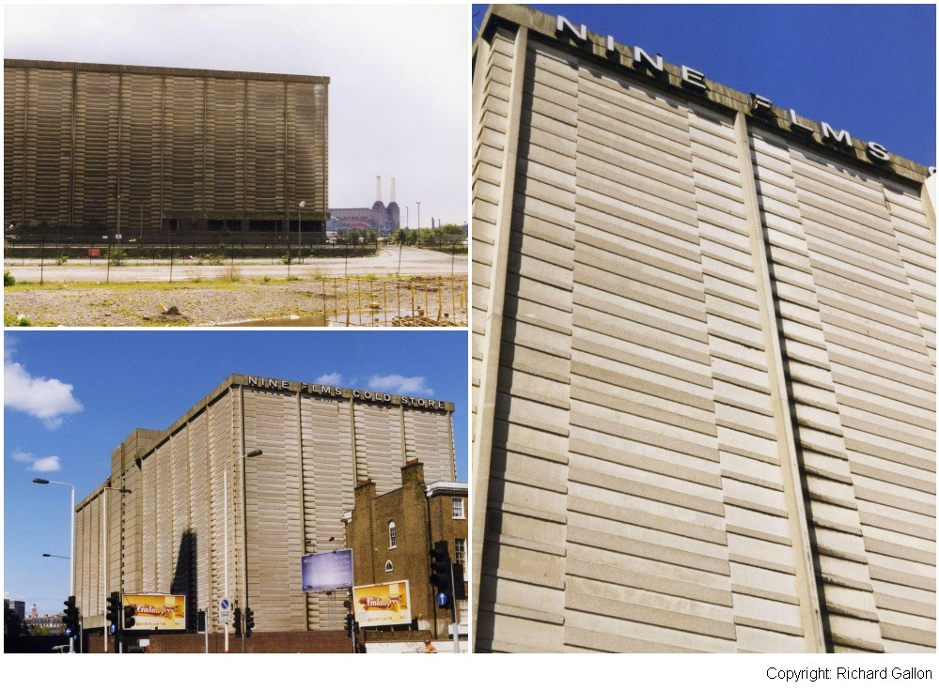

For 35 years between 1964 and 1999 almost every view of Vauxhall was dominated by one building – the Nine Elms Cold Store. And it wasn’t even the tallest.

Even when the much taller (88m) Market Towers[1]Since demolished in preparation for the ‘landmark’ (what – another one?) One Nine Elms development featuring residential, office, hotel and retail space. came along in 1975, it barely succeeded in distracting the eye from the cold store. This giant, concrete, windowless, and for years redundant, monolith was very much Vauxhall’s landmark and a symbol of SW8’s almost dystopian-looking late-industrial landscape.

For most of its life it stood empty, or if not quite empty then abandoned by its owners. It was often emphatically not empty. According to legend it was used as a cruising ground, a performance space, a recording studio, and a temple for devil worship. Some say people died in there, and that it featured in an episode of The Sweeney.[2]‘In From the Cold’. Season 3 Episode 2. Can these things possibly be true?’ Urban myths surely.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s start almost at the beginning.

1964–1979: The Chill Years

The Nine Elms Cold Store stored cold things for less than half of its life. It held meat, fish, butter and cheese for 15 years then nothing for 20.

It opened on 30 November 1964[3]‘£1M. Cold Store Opened’, The Times. Tuesday, 1 December 1964. on land previously occupied by the South Metropolitan Gas Works which in turn had been built on the site of Price’s Patent Candle Company‘s Belmont works. The current occupant is the St George Tower and the green-glass, wing-topped St George Wharf apartments. Were these to be pitted against the derelict cold store in an ugliness competition it’s difficult to say who would win.

Anyway, the cold store was built, filling in Vauxhall Creek – the last vestige of the river Effra – in the process.[4]Jon Newman (2016), River Effra: South London’s Secret Spine. Oxford: Signal Books.

The opening merited a mention in The Times which reported that ‘Europe’s most modern cold store’ had cost its owners London Cold Storage Co (one of the Associated Fisheries Group of Companies) more than £1 million to build. With a capacity of two million cubic feet it could hold more than 16,000 tons of food[5]The Times, ibid. and goods could be loaded and unloaded there faster and more efficiently than at any other cold store in Europe.[6]Refrigeration and Air Conditioning, Volume 68, Nos. 802–807. Its purpose was to store produce for frozen-food processors and distributors.[7]‘Quick Turn-round at New London Cold Store’, Commercial Motor, 11 Dec 1964.

But why here? Why Nine Elms?

One reason was that the site was available. The gas works had disappeared in 1956 and the site was being used as a coach park. According to one account, ‘Here a thieves’ market thrived, carefully observed and recorded by police officers watching from the top floor windows of Brunswick House.’

The location had excellent transport connections – river, road, and rail. Two barges could be unloaded simultaneously at the Cold Store’s 90ft Thames jetty[8]Refrigeration and Air Conditioning, Vol. 68, Nos. 802–807. and eight lorries at a time could use the four covered loading bays, according to a report in Commercial Motor.[9]‘Quick Turn-round at New London Cold Store’, Commercial Motor, 11 Dec 1964. ‘Hydraulic dock levellers are used at the lorry bays and electric pallet trucks and other mechanical aids are widely used,’ swooned the periodical in its report on the opening of the cold store.

In 1965 most of Nine Elms (including the site of the New Covent Garden Market and the since-shunted flower market) was occupied by railway yards. Today, the area’s railway history is all but forgotten but for 10 years from 1838 the area boasted its very own and quite grand railway terminus which was the end of the line for trains coming in from Woking and later Southampton. Nine Elms Station stood at the end of Nine Elms Lane (then just called Nine Elms) which at that time emerged onto the Wandsworth Road roughly opposite the end of Miles Street (not Parry Street, as now). In 1848 the line was diverted before it reached the station to the new terminus at Waterloo via a new station at Vauxhall. The now-sidelined (literally) Nine Elms area became a massive railway yard and for over 120 years served variously as a carriage and wagon works, a goods depot and a locomotive depot.

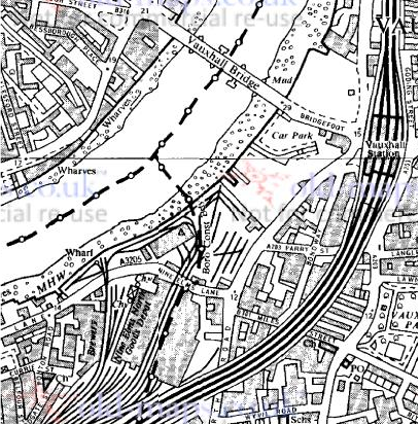

When it was built in 1965 the Cold Store was served by lines which reached it by crossing Nine Elms Lane, as this map from around 1967 shows.

At this point, Nine Elms Lane still met the Wandsworth Road just north of Miles Street. It was presumably rerouted to its current position (opposite Parry Street) in the early 1970s when New Covent Garden flower market was built.

Sadly the Cold Store’s triple-transport-threat status was short-lived – the railway yard closed just two years later, in 1967.

1979–1999: The Wilderness Years

In 1979, 15 years after it opened, the Nine Elms Cold Store closed. Why?

Advances in refrigeration, the increase in air transportation, the demise of river-based haulage seem likely factors. And Associated Fisheries’ cold storage business had been badly affected by the UK’s 1973–75 recession.[10]‘Associated Fisheries declines’, The Times, 9 July 1981. But the value of the site must have played a significant role. In fact, the Chairman of Associated Fisheries suggested so much as far back as 1973 when the Cold Store had been open for less than a decade:

Giving news to shareholders of Associated Fisheries […] Mr P. M. Tapscott, chairman refers to the proposed development of the Thames frontage on the south side of Vauxhall Bridge and the fact that AF’s Nine Elms cold store, a site of 1.6 acres, adjoins this development. Possibilities of re-development are, therefore, being closely examined.[11]‘Chairmen’s Reports’, The Times, 28 Nov 1973.

London Cold Storage divested itself of the site pretty quickly after the Cold Store closed. In November 1980, The Times reported that contracts had been exchanged on the sale of the cold store and other property for £1.67 million cash with completion due on February 5.[12]’Associated Fisheries’, The Times, 21 Nov 1980.

Which is when things begin to get really interesting at the Nine Elms Cold Store.

Development Hell

Why did it take 20 years for the Cold Store to be demolished? There’s probably a whole book to be written about it if there’s an audience for property development horror porn. Suffice to say that in the early days it involved Ronald Lyon, who could be described as a colourful property developer with an interesting business past.

Lyon got his hands on the Cold Store after the first proposal for the Effra site (which included land on both sides of the bridgefoot) fell apart.

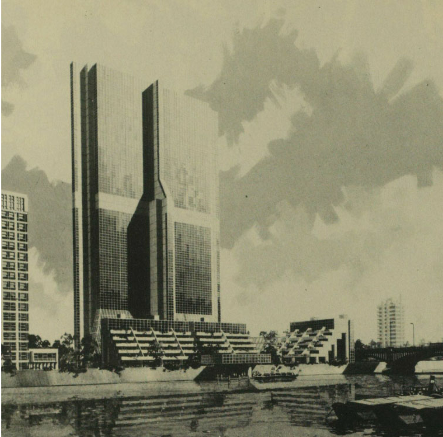

The extraordinary 150m ‘Green Giant’ project designed by architects Abbott Howard would have included 100 luxury apartments, 30,000 square metres of office space earmarked for Esso, and a gallery to hold the Tate’s sculpture collection.

Then along came Lyon, whose Arunbridge company was granted a controversial Special Development Order from the then Secretary of State for the Environment, Michael Heseltine. This SDO would essentially allow Arunbridge’s office scheme to run roughshod over normal planning procedures. Despite this unfair advantage, Lyon failed to find the funding and the scheme collapsed. The Swiss Bank Julius Baer & Co was holding the site as security against a loan and they sold it to Samuel Properties[13]‘Samuel Properties plans 1,000 flats on Green Giant site’, The Times, 8 May 1985. who in turn sold it to a Middle Eastern consortium, who then… well, you get the picture. One of the ongoing barriers to development seems to have been the Borough of Lambeth’s objection to swanky residential schemes of the kind it now welcomes with open arms.

Quite how it took two decades to knock the Cold Store down isn’t clear but one factor seems to have been the cost of demolition. One person involved in a government scheme to build a new Home Office on the Effra site recalls that the Cold Store was to be addressed late in the scheme due to the cost of demolishing it.

After a long, lingering decline, the Nine Elms Cold Store was finally put out of its misery in (I think) 1999. Thankfully Jonathan Bell was around to record the event for posterity.

But until then, the Cold Store could hardly be described as empty…

Screen Appearances

London film makers in search of ‘bleak industrial landscape bordering on dystopian’ needed to look no further than Nine Elms – even before it was abandoned. Less hackneyed, less iconic, and more alien than Battersea Power Station, the Cold Store made fleeting background appearances in films such as Villain (1971), a crime film starring Richard Burton, and The Optimists of Nine Elms (1973) with Peter Sellers. But the most thrilling use of it must surely be the 1976 episode of cop series The Sweeney called ‘In From the Cold’, which featured this exchange on the very roof of the Cold Store.

Cruising to Casualty

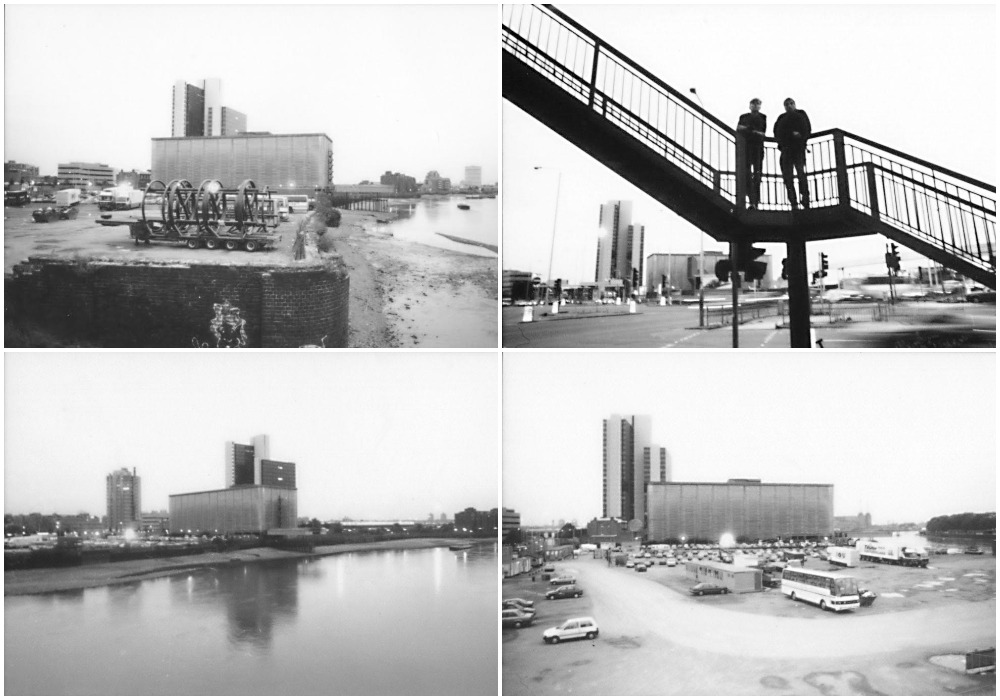

After the closure of the Cold Store in 1979 its most frequent visitors were gay men, who adopted it as a night-time cruising ground, handy for rounding off a night out at the nearby Royal Vauxhall Tavern or the Market Tavern which was housed in the Market Towers high-rise. The Cold Store was a bedroom and playroom to many liaisons over the years but was notorious for providing pleasure and danger in almost equal measure – sometimes with fatal consequences.

One visitor who narrowly escaped death but lived to tell the tale is John (not his real name):

The Nine Elms Cold Store was where you went after a night at the Market Tavern if you didn’t get lucky. You crossed Nine Elms Lane via the footbridge (pedestrians were made to navigate all the Vauxhall Cross main roads that way back then) to a gate just to the left of the wall which still shelters Brunswick House from Nine Elms Lane today. The steel gate was 10 feet high, padlocked, and there was barbed wire across the top, but a gap had been forced open at one side through which you could squeeze to get in to the grounds of the cold store. There was no such thing as site security in those days.

“It was about a 20-metre walk from the gate to the building’s entrance which was simply a big gap in the concrete – no doors. People would stand just inside the entrance so they could see who arrived – if you went any further in it was pitch black.

“Assignations would generally take place further back in the building where there were various rooms. Generally, the only things you could see were glowing cigarette tips. Sometimes people used lighters to find their way around. If you looked back you could see the doorway from the street lights outside, but nothing else. It was scary but that was part of the excitement.

“Not only was it dark but it was hazardous and you had to know what you were doing. If you didn’t turn left after the entrance you risked toppling down a 40 ft pit. Which is what I did at about 1am one Wednesday night in May 1990.

“I’d been to the Market Tavern’s Market Leathers night. I was a horny 22-year-old, I hadn’t pulled and was head-to-toe in fetish-wear – full rubber gear with 20-hole Doc Marten boots and a bomber jacket. I’d only been to the Cold Store two or three times before because I found it too scary.

I squeezed through the gate – being ultra-careful not to damage my precious rubber gear – and walked to the opening. After a brief hello to a friend who was already there, I walked on in. And then I very suddenly felt ‘funny’ – that’s how I describe it to this day. I thought I was fainting but actually I was falling 40 feet through the air. But because it was dark I didn’t know that. One reason I survived was because my body was completely relaxed thanks to my blissful ignorance.“I must have passed out. When I came round I could see lighters way above me around the top of the pit as people peered in to see what had happened to me. My friend was up there and I remember him asking with concern, but somewhat missing the point, ‘John! Did you lose your glasses?’

“Then a rescuer – someone I’d never met before – appeared almost magically from somewhere close by, scooped me up and somehow carried me outside and back out the gate. I’ve no idea how.

“He got me to his car which was parked on Nine Elms Lane. I’d badly damaged my hand which was bleeding profusely and he said he’d have to clean it up a bit and stop the bleeding. He opened the boot and a pile of wigs and dresses fell out – it turned out he was one of the main drag queens of the day. He found the kitchen towel roll he used for taking off his make-up, cleaned me up, and started driving me to hospital.

“Now at that time it seemed as though every week’s Capital Gay newspaper contained a story in which Casualty staff expressed how pissed off they were with stupidity of people who went cruising in the Cold Store so I refused to go to hospital and he took me home instead. A few hours later my flatmate – seeing the state I was in – forced me to go to the A&E at King’s College Hospital in Denmark Hill where I lied and told them I’d been hit by a car.

“At the time my injuries seemed minor considering the fall I’d taken. I’d chipped a bone in my right foot, my hand was a mess – the size of a football – and I had a sore neck. It was only in later life that the effects became clearer. Three of the discs at the base of my neck were compressed and have steadily deteriorated, meaning I sometimes lose feeling in my arms. I’ll have to have an operation at some point.

“My right hand was still bandaged a few months later when I was due to sit the final exams for my four-year university course. There was no way I could take them because I couldn’t write. Eventually it was agreed that I would take three exams by dictating the 3,000-word essays into a cassette recorder. I got a 2:2.

“I know that I was lucky to get out of the Cold Store that night with my life. Other people didn’t. What saved me was not knowing I was falling and it may have helped that I was a bit drunk. I think my boots protected my feet and ankles from greater injury. And, of course, I was saved by the brave and decisive actions of that off-duty drag queen.

“I did go back to the Nine Elms Cold Store but only once and in the daytime to try and find my glasses. Looking down over the edge of the hole was terrifying and I was shocked to see just how far I’d fallen. I never returned after that.”

The Cold Store Tapes

In 1990, avant garde musicians Chemical Plant hatched the idea of using the abandoned Cold Store not just as a recording studio, but as a part of the music.

Duo Ashley Davies and Richard Gallon created music and sounds which have been described as ‘a balance of hypnotic percussion and experimental/ambient sound montages, mixed with ethereal vocals and paranoid commentaries’. They invited saxophonist Fiona Sail and vocalist Pinkie Maclure to join them at the Nine Elms Cold Store on Saturday 9 June 1990 to create something special and unique, and the result was The Cold Store Tapes.

Chemical Plant’s Richard Gallon explained how it came about:

The music we were making at the time was loosely termed ‘industrial’ and we were interested in using such a big industrial space to provide the atmosphere for our recordings.

At that time it was still possible to just wander in. We went during the day but once you left the ground floor where it was open and light came in it was quite a spooky place. I particularly remember Fiona walking in through a door into one of the huge spaces upstairs while we were all playing. The loud echoing blast of the sax as her shadow appeared in the doorway gave me quite a start.

The idea was essentially to record the sound of the building itself and Pinkie found that she could almost make chords with her voice there, the delay from the insides of the building being so long and sustained.

We recorded everything on a portable stereo cassette recorder. Every sound was made either with voice, saxophone or pieces of metal and other objects we found there. The cassette and later CD releases were made up of edited versions of the recordings made with no effects or other treatments added so the sound is exactly as it was recorded inside the building.

Richard later put together this video using photographs and Super 8 film shot at a later date:

and took these photographs at around the same time:

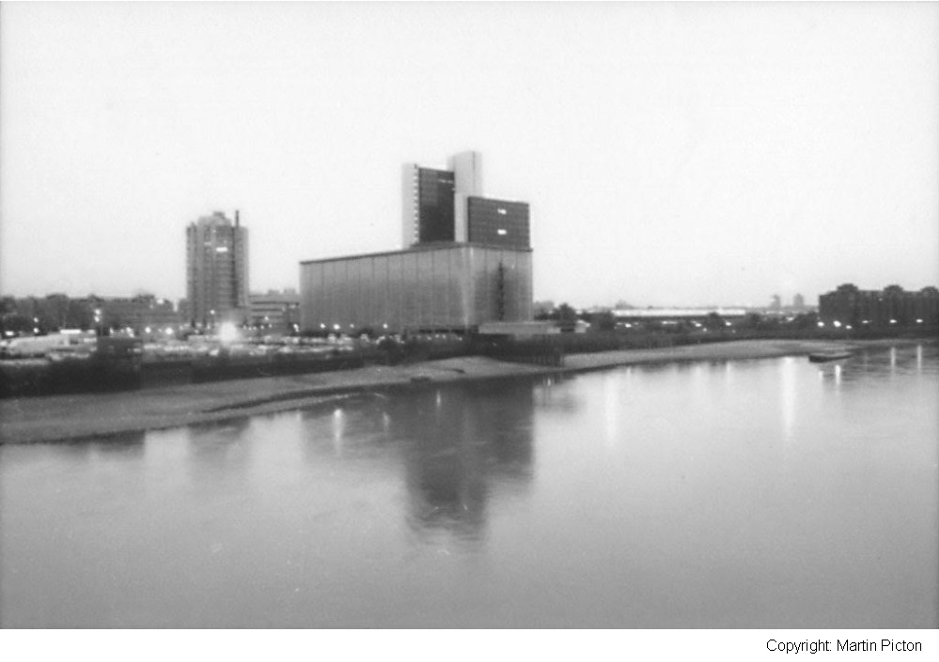

These four evocative photographs were taken by Martin Picton for use in promoting Chemical Plant’s The Cold Store Tapes:

The Cold Store Tapes are available on a CD which ‘captures this improvised acoustic performance in all of its raw intensity and allure’ from dor.co.uk.

Satanic Wrongs

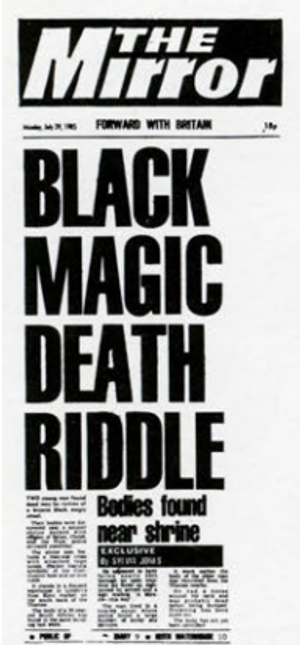

One of the alarming and persistent stories about the Nine Elms Cold Store is that it was a venue for black magic, devil worship, sacrifices, and orgies (it did see more than its fair share of orgies over the years).

In 2012, a contributor to the Urban 75 online forum member wrote:

I can confirm there was something out of the ordinary going on here in the mid 80s. I was a Met Policeman at the time and we got called there to a dead body by an anonymous caller in the early hours of the morning. There was indeed a dead guy on the stairwell, I think it turned out he had fallen through a trapdoor in the roof to his death. However… on searching one of the floors we found, by torchlight, which was pretty scary, a chamber that had been decorated. There was a bed, an altar and various restraining devices attached to the walls and pillars. Some of these were child sized. Only way to describe them was like body harnesses for pinning people up in the air. From memory it turned out the place was used by a group of squatters who had taken over a derelict terrace nearby for filming. Not the sort of film I would like to have seen. It was indeed a scary place that night, I’ve no idea what the result of the investigation was as I wasn’t involved past that night. Could have been an orgy/film/black magic set, there was all sorts of weird stuff in the room.

In fact, that devil worship paraphernalia was probably left over from a not wholly successful ‘happening’ held there in 1985 which featured ‘religious-blasphemous content and imagery’. Rob La Frenais wrote about it in Performance Magazine:[14]‘Happenings’, Performance Magazine, Issue 36 Aug/Sep 1985.

At the start there were all the right signs. A sense of nostalgia as we picked our way across the rubble at dusk, to dive into a foul-smelling hole which connected with steps that led us up and up to an antechamber, from which it was possible to see others, coming from all directions, as if drawn by a radar echo to the central focus of the building. I would not have been surprised to have been catapulted in to the invisible tennis scene in Antonioni’s Blow-up. Once inside, things looked promising too. A cavernous place, reeking of incense, with various ‘shrines’ scattered around and the confused participants making last-minute preparations.

From this point things started to go downhill. After wandering around freely, we were all herded back into the antechamber, and the organisers proceeded to make their One Big Mistake which was to kill any spontaneity that might have been present. This was to organise us into a ‘guided tour’ conducted by an ‘archbishop ‘ with an unmistakeable actorly voice, who was to introduce us to each aspect of the ‘cathedral’. The audience, which was sizeable, and who had come to participate in what had all the trappings of a ‘marginal’ event, – a seemingly illegally entered building, darkness, blasphemy (the altar was a large double bed) – immediately started showing resentment about being herded about by a bunch of drama students. The veteran extremist performance artist, Ian Hinchcliffe, who lives locally, and was here to check out events on his manor, immediately hurled abuse and smashed a handy light fitting before retiring to the pub. The organisers nervously regained control, but the evening, wonderful place, wonderful setting was lost. The genre had been hijacked, and was found wanting.

The next edition of Performance Magazine[15]‘Life and Art’, Performance Magazine, No. 37, Oct/Nov1985. featured a letter from an Andy Hazell of SW8, presumably one of the organisers:

Dear Performance Magazine, Some time ago, you like many others attended the performance in Nine Elms Cold Store, […] a night of organised chaos, power failures, headbangers and spiritual bad times. Well, I just thought you might like the enclosed as a memento. I returned from Africa to find the police had axed down my front door and turned all my worldly goods inside out hunting for evil murder weapons. Suppose it just goes to show how life and art are inextricable entwined. At least the Mirror thinks so.

Is it possible that the Metropolitan Police had found a body and the props from the happening, put two and two together and made five?

The Poetry of the Cold Store

Why did and does the Cold Store evoke such myths? Why did it draw musicians and artists to it? Perhaps because it was bewildering – how could something so big, so useless, and so ugly sit so obstinately on the riverside for so long? Even today, people talk of it almost wistfully, such it its power in the memory. Biba Dow, partner at Dow Jones Architects, even nominated the Nine Elms Cold Store as ‘the building I wished HADN’T been demolished’.[16]‘Life and Art’, Performance Magazine, No. 37 Oct/Nov1985.

It seems that each writer drawn to the Cold Store has tried to make sense of it with their own metaphor. For Will Self it was ‘a beehive of concrete beams, Venetian-blind-slatted; seeping’[17]Iain Sinclair, ed. (2006). London: City of Disappearances. London: Hamish Hamilton. while to the protagonist in Gabriel Gbadamosi’s novel, Vauxhall, ‘it looked like a dead pyramid for people who didn’t believe in God’.[18]Gabriel Gbadamosi (2013), Vauxhall. London: Telegram Books.

Perhaps people are forced to reach for metaphors because at the end of the day the Nine Elms Cold Store looked like very little else on earth and certainly nothing you might reasonably expect to find within view of the Palace of Westminster. Self – who lived nearby in Stockwell – wrote:

Although longer than it was broad or high, and from Vauxhall Bridge resembling a great sarcophagus, or the sole remaining buttress of a mighty defensive earthwork, the impression this disappearance leaves in my psyche is resolutely cubic. The Cold Store – a beehive of concrete beams, Venetian – blind-slatted; seeping. In certain lights the horizontal stria [sic] seemed to have a pattern of impressions, the bas-relief of some ancient Mesopotamian culture where frozen produce was needed for the afterlife.

At its peak the Store held anything up to 16,000 tons of chilled meat, together with – as one of its admirers hymns it – ‘some butter and cheese’. Oooh, I love that ‘some butter and cheese’: the churned-up products of the massacred beasts lying alongside them in freezing chancels and icy transepts.

To leave the last word on Vauxhall’s Nine Elms Cold Store to Self:

Only now, with heavy pinion of the Cold Store removed, have bourgeois aspirations begun to soar. A preposterous giant tuning fork has been erected by the Council in lieu of a bus stop, the gull wings of St George Wharf above, hard evidence of mass faith in ever-rising property prices. December 2004. I stroll through the brushed-steel atria and columnar courtyards of the new development. In through a quarter acre of plate glass, an African security guard dozing behind his plinth. A vast plasma screen dominates the lobby, on it Sky News conducts an interview with the latest hack to have banged the former Home Secretary’s former mistress. Where have they gone, those 16,000 tons of meat, some butter and cheese?

Addendum – ‘The Optimist of Nine Elms’ by Paul Bernays

In April 2024 film maker Paul Bernays pointed us to this short cine film he made in 1983 about the Thames at Vauxhall, featuring the Cold Store and Vauxhall Bridge.

References

| ↑1 | Since demolished in preparation for the ‘landmark’ (what – another one?) One Nine Elms development featuring residential, office, hotel and retail space. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | ‘In From the Cold’. Season 3 Episode 2. |

| ↑3 | ‘£1M. Cold Store Opened’, The Times. Tuesday, 1 December 1964. |

| ↑4 | Jon Newman (2016), River Effra: South London’s Secret Spine. Oxford: Signal Books. |

| ↑5 | The Times, ibid. |

| ↑6 | Refrigeration and Air Conditioning, Volume 68, Nos. 802–807. |

| ↑7, ↑9 | ‘Quick Turn-round at New London Cold Store’, Commercial Motor, 11 Dec 1964. |

| ↑8 | Refrigeration and Air Conditioning, Vol. 68, Nos. 802–807. |

| ↑10 | ‘Associated Fisheries declines’, The Times, 9 July 1981. |

| ↑11 | ‘Chairmen’s Reports’, The Times, 28 Nov 1973. |

| ↑12 | ’Associated Fisheries’, The Times, 21 Nov 1980. |

| ↑13 | ‘Samuel Properties plans 1,000 flats on Green Giant site’, The Times, 8 May 1985. |

| ↑14 | ‘Happenings’, Performance Magazine, Issue 36 Aug/Sep 1985. |

| ↑15 | ‘Life and Art’, Performance Magazine, No. 37, Oct/Nov1985. |

| ↑16 | ‘Life and Art’, Performance Magazine, No. 37 Oct/Nov1985. |

| ↑17 | Iain Sinclair, ed. (2006). London: City of Disappearances. London: Hamish Hamilton. |

| ↑18 | Gabriel Gbadamosi (2013), Vauxhall. London: Telegram Books. |