by Eric Dymock

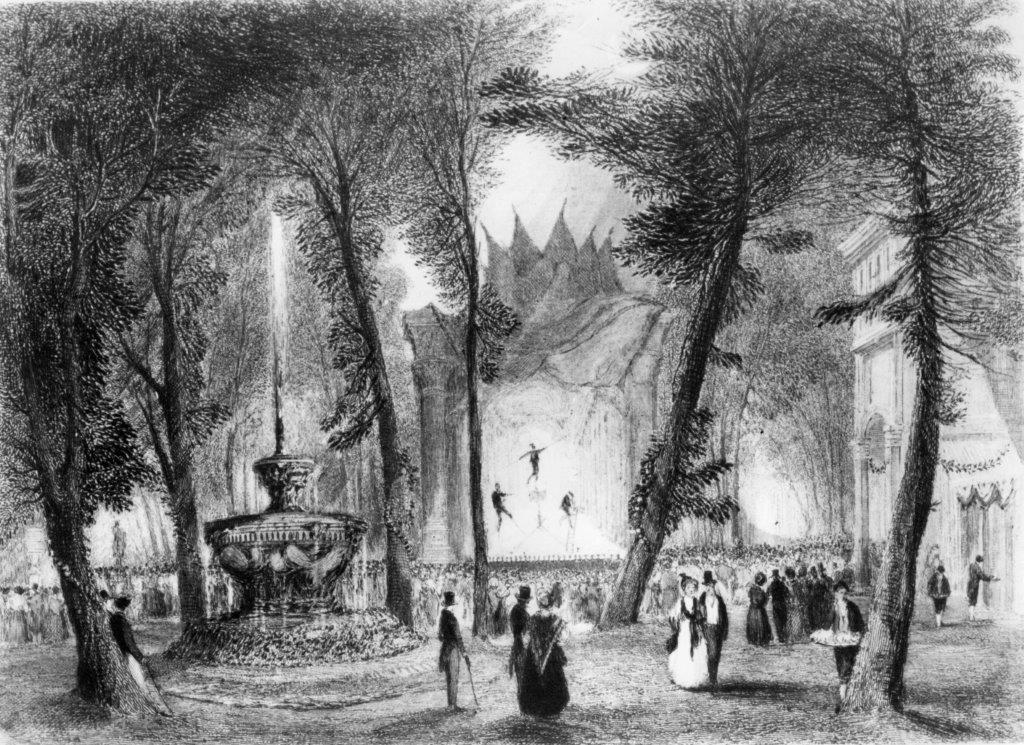

Why do all Russian railway stations carry the name of an English middle-class car? In the 1780s Michael Maddox, an English theatre manager and a visitor to Vauxhall Gardens, decided to export the concept of the pleasure garden to St Petersburg, Russia. The new attraction was called ‘Vokzal’, after the location of its London inspiration. In 1837 the first Russian railway ran from St Petersburg to the Pleasure Gardens and the station was called Vokzal (Вокзал). The word endured as a generic term for railway stations, so St Petersburg, for instance, has Vitebsky Vokzal, Finlyandskiy Vokzal, Ladozhskiy Vokzal and Moskovsky Vokzal, at the junction of Nevsky Prospekt and Ligovsky Prospekt, the oldest and busiest.

Vauxhall always was more than a car. The district on the south bank of the Thames since the Middle Ages had, by the 21st century, entered British industrial and social history. For more than a century the name has been applied to horseless carriages, limousines for Edwardian royalty and aristocracy as well as a dynasty of sports cars with an international reputation. Vauxhalls carried staff officers to battle in the Great War and spanned distinctions of class and wealth afterwards. Joining General Motors in 1925 transformed it from a purveyor to the nobility and gentry, to a mass market manufacturer claiming a little piously, “Quality is a right, not a privilege.”

Vauxhall was often subject to loose language and a casual disregard for spelling. In the 12th century, up-river from Westminster, it owed title to the unpopular Plantagenet King John (1167-1216), of Magna Carta fame. The miscreant monarch had granted Fawkes de Breauté, an unwholesome mercenary, the Manor of Luton, also making him Sheriff of Oxford and Hertford. By way of thanks for serving as a royal fixer, the King issued a decree marrying de Breauté to a rich heiress, Lady Margaret de Redvers. Widow of Baldwin de Redvers of the powerful Fitzgerold family, she had a nice house by the river in leafy Lambeth. After she married de Breauté the Thames-side residence became known as Fawke’s Hall, Fox Hall and finally Vauxhall. Once young Henry III came to the throne, and following an unsuccessful plot to seize the Tower of London, de Breauté, along with many of John’s cronies, fell from favour, fled to France and died in penury. Fawke’s Hall was quite properly restored to the Fitzgerolds.

The first published mention of Vauxhall Gardens as a resort of pleasure appeared in the diary of John Evelyn ion 2 July 1661, under its original name, The New Spring Garden. His fellow diarist Samuel Pepys was to become a regular visitor, who mentioned it in his diary of 29 May 1662.

Vauxhall Gardens was patronised by Charles II, prospered for nearly two centuries and in April 1749 Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks was played to a paying audience. The Rt Hon George Canning featured the Gardens in poetry, Fielding, Smollett and Dickens visited, William Makepeace Thackeray described them in Vanity Fair and the Prince Regent liked to dine there. However, by the 19th century its new habitués, gamblers and ladies of the night, led to its decline. In 1836 Vauxhall was the starting point of English balloonist Charles Green’s flight to Weilburg Germany, an 18-hour trip of 480 miles (772km), but the Gardens’ rustic attractions were subsiding due to industrial growth. Matters came to a head in 1857 when Scottish engineer Alexander Wilson set up an iron works at 90-92 Wandsworth Road, by Vauxhall Junction railway station. Wilson made refrigeration plant, boilers, Excelsior Steam Pumps and had an Admiralty contract for high-pressure engines in naval pinnaces. He also turned out compound twin and triple steam expansion engines for Thames river vessels plying between Westminster and Hampton Court.

The area became absorbed into the sprawling cityscape of Greater London, and industrial smoke and grime from the railway and Wilson’s works finally did for the Gardens, which closed in July 1859. Wilson’s enterprise survived until 1894 before facing financial collapse. The proprietor proved an indifferent businessman so a receiver John Henry (Jack) Chambers was called in and Wilson went off to become a consulting engineer. With a workforce of 150 the firm became The Vauxhall Ironworks Company Ltd.

Following reorganisation at the turn of the century, one of its brighter apprentice marine engineers, Frederick William Hodges, suggested making cars. To find out how, the management bought one, probably a Canstatt-Daimler, and built two belt-driven replicas. Hodges tried out different sorts of engines, some ambitious with opposed pistons, which he tried out on his boat Jabberwock, and it was 1902 before he and J. H. Chambers, the 1896 receiver, accomplished the first production Vauxhall vehicle. Harry Pratt, who bored-out the cylinder of the first engine, remained with Vauxhall his entire working life, retired in 1946 and died in 1964 aged 93. Produced in the spring of 1903, Harry Pratt’s car began a lineage that was to become Britain’s longest-established motor manufacturer.

Chambers drew up a second car, then resigned in 1904, taking his expertise back to the family business, engineers, millwrights with a bottling machinery sideline in Belfast. At 15-23 Cuba Street he made a car like the Vauxhall, which sold well with a Northern Irish market pretty much to itself. Chambers’ factory moved to bigger premises in 1914 at 126 University Street, and the Vauxhall design remained the basis for vehicles made until 1927, making Chambers’ company the longest-surviving car maker in Ireland.

Manufacturing cars in the early years of the century was something of a gamble, so the Vauxhall Ironworks partners stuck to established principles. Their engineering was good and the cars well made, with a single cylinder and chain drive. About 70 were sold the first year, but by the time the 3-cylinder 12/14 was ready for production, the old ironworks lease was running out. Car manufacture had been crammed into four times the area of the former marine engine works and there was no room to expand.

A bigger factory was needed, so Vauxhall moved to Luton, by coincidence to what had been Fulk’s old country estate, amalgamating with neighbouring West Hydraulic Engineering to form Vauxhall and West Hydraulic Ltd. A site of six acres, one rood and twenty perches, or nearly 2.8 hectares, on Gallows Road (later more circumspectly named Kimpton Road) was bought for £1750 on 18 April 1904. Luton was expanding industrially. The municipality had just installed public electricity; a site was available, there were plenty skilled workers from the town’s traditional hat-making industry and the works had a siding on to the Midland Railway’s main line.

The car business separated formally from West Hydraulic in 1907, yet its variety of products was almost its undoing. None got the attention it deserved, so the car business was hived off for £17,000 by young director and shrewd merchant banker Leslie Walton. He and Percy Kidner became joint managing directors of Vauxhall Motors, William Gardner was chairman and the former Wilson apprentice F.W. Hodges taken on as consultant engineer. Alfred John Hancock joined as works organiser, and the group was completed with the recruitment of gifted young engineer Laurence Henry Pomeroy (1883-1941). A premium apprentice with the North London Railway and former draughtsman with John Thornycroft at Basingstoke, Pomeroy was only 23 when he joined as Hodges’ drawing office assistant, and although he left in 1919 his work had a profound influence on Vauxhalls for two decades more.

Fulk Le Bréant’s enduring legacy was a heraldic emblem. A griffin or gryphon, the half lion half eagle, had hung over the entrance to the old Vauxhall pleasure gardens and was kept for Le Bréant’s second fiefdom, Luton. It became a feature of Vauxhall cars. Another, the famous bonnet flutes, appeared on the engine cowling of the 1905 18HP, a styling touch suggesting speed and airflow. It may have been gimmickry but it lasted 50 years and the shape of radiator and engine cowling became an industrial icon that identified more than a make of car. On suburban driveways they were emblematic of the emerging British middle class. Just as the mock-Parthenon radiator of the Rolls-Royce identified the upper class, or the Ford oval the blue-collar working class, Vauxhall’s mid-Atlantic style of the 1930s following its capture by GM, marked out staunch prosperous middle Britain.

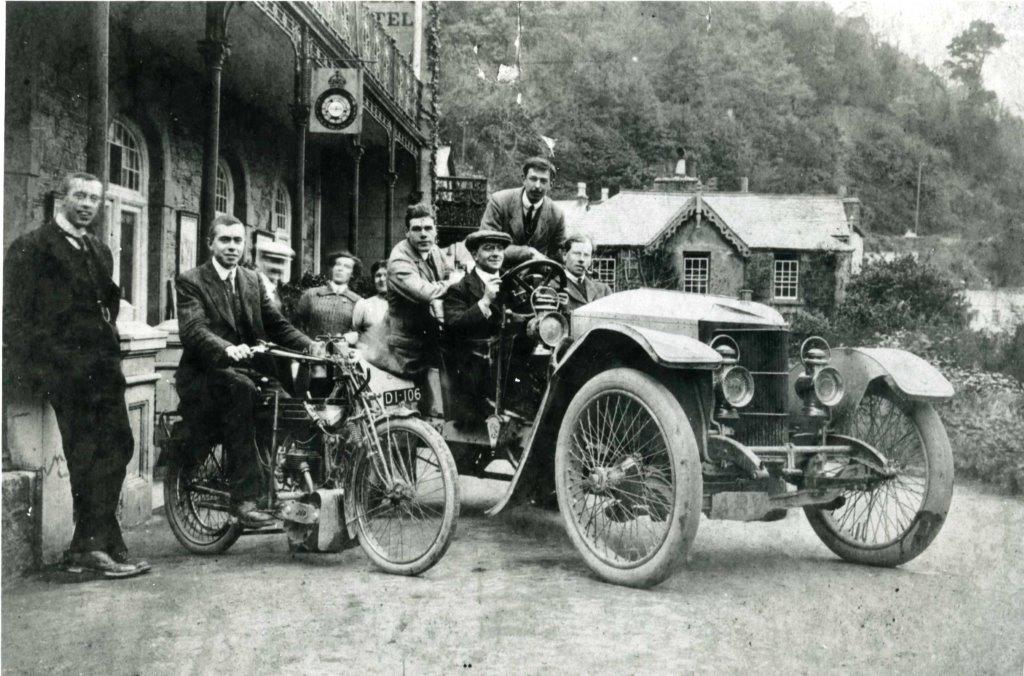

Taking part in sporting competition secured Edwardian reputations and Vauxhall was keen to make its name. The ambitious Pomeroy was enthused when the RAC published regulations for its 2000 Miles (3219km) International Touring Car Trial of 1908 and the directors resolved to develop a car for it. The designer was quick off the mark. The formidable F.W. Hodges was on holiday in Egypt, so his young understudy started work at once on a radical new design. With no chance of Hodges catching the next flight home, Pomeroy worked without interference and the company entered a prototype known as the Y-type. Later A-types or 20HP cars ensured Vauxhall’s place among great Edwardians.

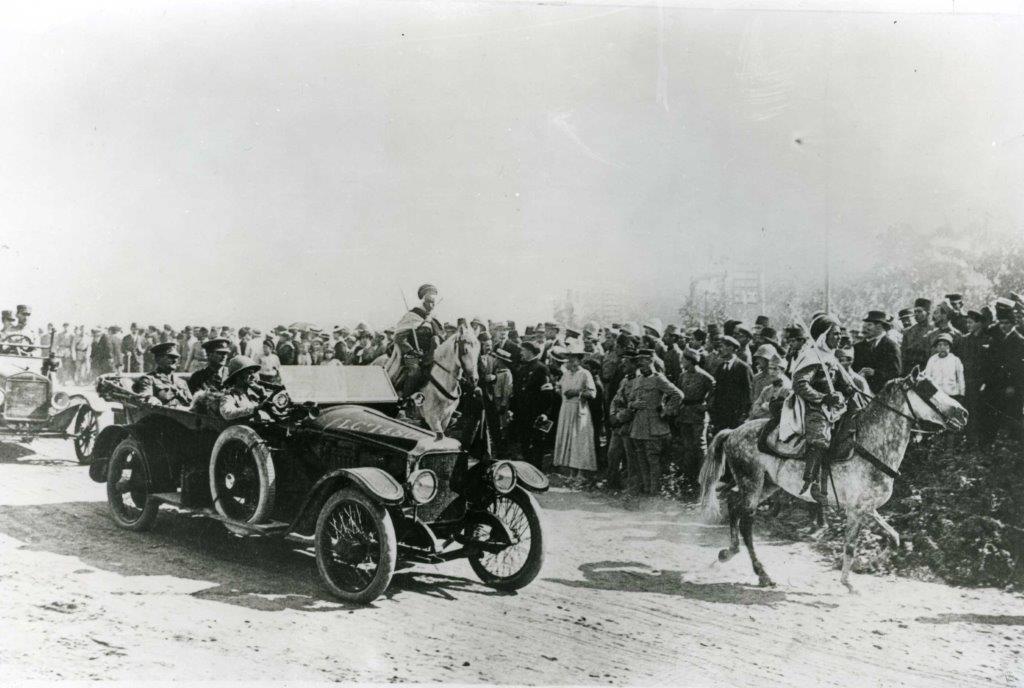

Work cascaded from the drawing board of the talented Pomeroy. In 1910 a motoring competition formed another Vauxhall landmark. Kidner was eager to take part in the trial organised by Prince Heinrich of Prussia, enthusiast brother of Kaiser Wilhelm II. The long-distance reliability test, to which the Prince gave his name, combined the prestige of a Monte Carlo Rally with the social cachet of Ascot. It followed a tortuous 1150-mile (1850km) route to Munich from Berlin, and for many of the 200 entrants the aristocratic patronage amounted to a command performance; an archduke sponsored Ferdinand Porsche’s Austro-Daimler.

The Prince had been instrumental in endurance trials since 1907 and the 1910 event was tougher than ever, with 17 special tests from Berlin to Bad Homburg via Braunschweig, Kassel, Nürnberg, Strasbourg and Metz. Road sections alternated with hill-climbs and speed tests, cars had to be fully equipped and all four seats occupied. Austro-Daimler entered three and finished first, second and third, a crushing defeat for Mercédès establishing another industry precept; motor racing was not only useful for motivating customers but also provided encouragement for management and engineers. Porsche had been determined that his production Austro-Daimler would meet Mercédès’ challenge and developed it into one of the best sporting cars of the 1920s.

Pomeroy’s engineering was almost as wide-ranging as Porsche’s and he relished his opportunity. Notable Vauxhalls after the Y-type included some capable of competing with Porsche’s Austro-Daimlers. Prince Henry’s regulations had encouraged long-stroke, large capacity engines, so Pomeroy adapted a 4-cylinder for a team of three. His 3.0litre, however, was no match for Porsche’s 5.7litre, nor was Pomeroy quite up to the advantages the Germans gained from clever interpretation of the rules, yet the Luton entry was trouble-free and all gained finishers’ awards. The 1911 production version at the Olympia Motor Show in October was duly called the Prince Henry.

Company publicity stressed that among the reasons for such a strong performance was light weight; the body and chassis were narrow and tapered, and Pomeroy gave a great deal of thought to the precise curves and flutes on the radiator and bonnet. He aimed at good aerodynamics and adequate cooling, although his son Laurence Evelyn Wood Pomeroy (1907-1966), technical editor of The Motor from 1936 to 1958 was sceptical. “Unfortunately the 3litre radiator had insufficient cooling area and was notorious for boiling if driven fast upon a summer’s day. Nevertheless this small light car was tremendous fun to drive and I remember as a boy long journeys sitting in the dickey-seat of my father’s two-seater.”

Arguably, the Prince Henry was the first true British sports car, although by no means the only conspicuous Vauxhall to claim the title. In 1909 A.J. Hancock drove a single-seater known as KN up Shelsley Walsh at record speed and went on to break Brooklands class records at 88.6mph (142.6kph). Whimsical names were a Brooklands custom; KN was an allusion to Cayenne pepper, advertised as “Hot Stuff”. The following October a narrow-bodied single-seater with KN’s engine became the first 20HP formally timed at 100mph.

By 1909 Vauxhall was making nearly 200 chassis a year, for each of which the coach-building industry constructed bodies. In 1910 nearly 250 were turned out, as well as commercial quantities of speed-boat engines. The cars were elegant and upmarket and in 1911, after Kidner won his class in reliability trials, were well regarded by the Russian Imperial family. St Petersburg again. Vauxhall set up a workshop there staffed by British fitters and printed catalogues in Russian.

Promoted to works manager in 1910, Pomeroy designed an ingenious overhead cam engine for the Prince Henry team cars which was, alas, never used. With astonishing prescience he proposed moving camshafts lengthways, bringing a second set of cams into play which altered valve timing and lift, effectively reconfiguring the engine. At slow speeds one set of cams provided smooth economical running, at high speeds others enabled the valves to gulp a bigger charge and produce more power. Engines with fixed valve openings could not manage both. Pomeroy’s invention was a generation ahead of its time but materials and techniques to make it work were not yet available. Each cam had to be painstakingly shaped by hand and it was the 1980s, when metallurgy enabled sufficiently tough steel, before variable valve timing was re-invented.

Kidner had another success in February 1912 with the C-type Prince Henry in Swedish winter trials. He constructed a canvas screen, rather like the dodger on a ship’s bridge to deflect snow, and drilled holes in the floor to draw in heat from the engine. He arrived at the Stockholm finish only to be excluded from results for being too far ahead of the field.

Vauxhall took part in the Coupe de l’Auto voiturette races of 1911, 1912 and 1913, and in 1914 twin overhead cam engines were designed for the TT and the French Grand Prix, but the company’s official competition programme was dogged by misfortune. Some cars only did well after being disposed of to private owners. Pomeroy’s influence was waning and although he spent much of the First World War experimenting with his clever camshafts, he resigned soon afterwards for a career with the Aluminum Company of America. His work with Pierce-Arrow and Peerless on engines and lightweight cars secured his reputation among the most inventive and prolific automotive engineers.

Pomeroy’s successor at Vauxhall, Charles Clarence Evelyn King, had an unconventional background for a senior engineer in the motor industry. Mystic and artist, he had been apprenticed as a mechanic with the Adams Manufacturing Company and the Société Lorraine. He left France during the war after trying to earn a living as a painter. Yet CEK, as he was known in company memos, was instrumental in Vauxhall design for 30 years.

Joseph Higginson of Autovac also influenced Vauxhall. In 1913, only weeks before Shelsley Walsh, he asked for a 4.5litre engine in a small Prince Henry. Pomeroy was equal to the occasion and came up with the first 30-98. Nobody was really sure what the figures represented – there was a 98-30 Mercédès about the same time – but the name stuck to a car with a narrow aluminium body and no doors. It also had a new rounded radiator, unlike the V-shaped Prince Henry prow, and Higginson used it to great effect, beating the latest Sunbeam and setting records that remained unbroken for 15 years.

Between 1914 and 1918 Vauxhalls were used by British staff officers. A 25hp Vauxhall took King George V to Vimy Ridge, another carried General Allenby on his triumphant entry into Jerusalem, and a Vauxhall was the first car across the Rhine into Germany following the Armistice. In the 1920s the 30-98 re-emerged as an 80mph (129kph) sporting rival for the Bentley, whose design had been influenced by WO Bentley’s recruitment of Vauxhall engineer Harry Varley.

Vauxhalls were still not for the man in the street, however, and the 2.3litre 14/40 of 1925, ostensibly at the cheaper end of the market, cost a formidable £750. The customer base was dwindling and even the splendid 4.2litre OE, with overhead valves and four-wheel brakes, couldn’t save the day. Despite its reputation Vauxhall was not making enough to remain in business. By 1924 it was selling only 1400 cars a year and although sales steadied in 1925, price reductions looked essential for 1926. Astonishingly, despite sleeve-valves being the ruin of distinguished makes in Britain and elsewhere, Vauxhall’s last independent engineering decision incorporated them in the extraordinary S-type. Sporting Vauxhalls were not selling well even though advertised as The Car of Grace that Sets the Pace. The S-type (slogan, Superexcellent) was expected to compete with Daimler, Rolls-Royce, and Sunbeam.

It was not to be.

Vauxhall made progress in due course but it was not an uninterrupted catalogue of achievement. Magnificent sporting cars were all very well but, together with Bentley and Napier, it would not have survived the Depression of the 1930s as an independent manufacturer. The cars were too expensive for that. Instead, under General Motors, Vauxhall changed its ways, went into popular cars and, drawing on the great corporation’s resources, could afford pioneering technical advances such as independent front suspension, synchromesh gearboxes and unitary chassis-less construction.

The success of Ford in Britain since 1911 had tempted General Motors. It had been looking for production capacity in the UK and after being rebuffed by Austin in 1925 it went after Vauxhall. Alfred P. Sloan Jnr, president of GM, encouraged a deal to buy the ordinary shares for $2.5m and by 1931 Vauxhall production rose to 5000 a year and GM put a £500,000 expansion programme in hand; it was still only a twentieth of what Austin and Morris were making, however. Except for some Chevrolets in Denmark in 1923 and Belgium in 1925, Luton was GM’s first manufacturing plant outside North America. In January 1929 Opel at Rüsselsheim, Germany was next, following the Opel family’s reorganisation of the company it had founded in 1898. GM bought 80 per cent of Adam Opel AG, taking this to 100 per cent two years later.

Photo © Eric Dymock.

Vauxhall stopped making expensive cars, ceased competing at the top end of the market and went over to popular volume production. It did not neglect innovation however, beating Rolls-Royce by several months in 1932 to synchromesh, and then pioneering unit body-chassis structures together with the celebrated “knee-action” independent front suspension. GM established a successful truck and van division, Bedford, gaining export sales that sustained the passenger car business through lean times. In 1933 Vauxhall and Opel together made more cars than GM was exporting from North America.

Vauxhall’s family cars, the Cadet, Light Six, Big Six, and later the Ten-Four, Twelve-Four, and Fourteen-Six were larger and softer sprung than contemporaries. They evoked Chevrolet or Buick style in 1937, with decorative grilles ahead of the radiator, although the traditional Vauxhall fluted bonnet survived. The 1930s finished with a flourish, the 25HP with a variety of bodies returning fleetingly to a classier clientele. By 1939 Luton was making 30,000 a year, one in ten of all the cars built in Britain and far from its position of being outsold five to one in the 1920s, Vauxhall joined the Big Six with Austin, Morris, Ford, Standard and Rootes (Hillman, Humber and Sunbeam-Talbot). Furthermore, it was selling as many Bedford lorries and light commercials as it was Vauxhall cars.

On the outbreak of war in 1939 car production stopped. Vauxhall made a handful of 10HP saloons for the government, turning instead to making a quarter of a million Bedford trucks for wartime service. The military QL was its first venture into four-wheel drive. Luton presses turned out five million jerricans; spare fuel canisters so robust that they were copied without reference to their German designers. The presses also made 750,000 steel helmets. Luton made six-pounder armour-piercing shells, and the sheet-metal department not only did development work on Mosquito, Halifax, and Lancaster bombers, but also became involved with mines and radar equipment. From 1942 military lorries were also being made at a new Bedford plant in Dunstable.

Vauxhall’s secret war included work on a batch of the first jet aircraft engines, but its grandest assignment was the development and manufacture of the Churchill tank. In 1940 the United Kingdom had only 100 tanks available for defence and Vauxhall took on the task of putting a new one into production as quickly as possible. Taking its title from John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough as much as Winston, Britain’s wartime prime minister, it was produced in a hurry to meet the emergency. Work on the Churchill continued regardless of a bombing raid by the Luftwaffe on 30 August 1940, in which 39 workers were killed. Twice as heavy as contemporary cruiser tanks, Infantry Tank Mk IV was slow, but reached production within a year even though the manufacturer felt obliged to put a note in the handbook saying, in effect, its imperfections were acknowledged but the need for fighting vehicles was urgent. Over 5,600 were built, proving adaptable and successful in North Africa, Italy, North-West Europe and the Russian front.

After 1945, obliged to export the bulk of its production to meet Britain’s war debts, Vauxhall resumed with cars almost identical to the pre-war H, I, and J. By the autumn of 1947, when horsepower was abandoned as a basis of car tax, there was little point in keeping the 10HP separate and it was amalgamated with the 12HP. During the course of a £40m factory expansion in 1948, the range was rationalised into the L-type Wyvern and Velox, with new frontage and boot but much the same middle. This was a practical way of introducing a new range, keeping up to the mark in appearance and preparing for the E-Series Wyvern and Velox in 1951, based on a 1949 Chevrolet although perhaps less well proportioned.

A wyvern was a medieval winged two-footed heraldic dragon that could have been confused with Vauxhall’s griffin symbol; velox was Latin for swift or rapid, a name coined by Vauxhall in 1913 for a 30-98, and both modern models were in for long production runs. In the company’s golden anniversary year of 1953, production exceeded 100,000 for the first time and included the millionth Vauxhall. The Luton plant expanded to 80 acres (32 hectares), employed more than 13,000 and once again a major (£35m) programme was put in hand to extend the car production building and finally move Bedfords entirely to Dunstable. Within four years there were 22,000 employees and turnover was £76m.

GM made tentative steps in the 1980s to promote Opel in Britain in co-operative competition with Vauxhall. It was rebuffed when the sturdy heritage of Fulk Le Bréant showed British buyers were reluctant to relinquish the treasured title. By the end of 1983 579 British Vauxhall and 224 Opel dealers were merged to become joint Vauxhall-Opel dealers. It was not long before they reverted once again to plain Vauxhall, which had come a long way from being the name of a South London, or even a St Petersburg railway station.

Eric Dymock

Motoring correspondent of The Sunday Times 1982-1995 Eric Dymock trained as an engineer, joined the road test staff of The Motor, covered grand prix motor racing for The Guardian and The Observer 1966-1980. Contributor to Thames Television and BBC motoring programmes, The Times, Financial Times, Daily Telegraph. Winner of four Jet Media Excellence Awards, the Guild of Motoring Writers’ Montagu Award, and the Jim Clark Memorial Award for 2004.

Eric Dymock writes:

Vauxhall Model by Model From 1903 by Eric Dymock (2016, ISBN 978-0-9574585-4-3) details the company and cars from their origins in Thames-side London, through Edwardian racing cars made in Luton, to its takeover by General Motors in 1927. It went over to popular models, pioneering synchromesh gearboxes, unitary bodies, and the famous knee-action independent front suspension. The Cadet, Light Six, Big Six, and later 10-Four, 12-Four, and 14-Six were 1930s family cars of genteel respectability. Mid-Atlantic styling after World War II brought Velox, Cresta and Victor. The Viva entered the motoring lexicon in the 1960s as Vauxhall returned to motor racing through Dealer Team Vauxhall, and later VXRacing winning the British Touring Car Championship. GM Europe brought the Opel-engineered Cavalier in 1975, first to Luton and then Ellesmere Port.

The book is now (2020) out of print, but Dove Publishing Ltd has a limited number of copies for sale at £30 including postage, signed by the author, and a few with presentation slipcases at £40.

Contact Dove Publishing, 5 Abbey Park, Torksey, Lincoln LN1 2LS or email eric@dovepublishing.co.uk. Payment through Paypal on application.