Vauxhall, or ‘Voho’ in estate-agent’s patter (the ‘Soho’ of the south bank), attracts gay people both as a place to live and for the clubs and bars that surround the site of what was once the Vauxhall Gardens open-air resort (1661–1858).

One notable event in the history both of the Gardens and of the capital’s gay life was the Ridotto al Fresco or outdoor masquerade and ball held on 21 June 1732 to relaunch the Gardens under a new management. Among those attending was ‘Princess Seraphina’, a trans person called John Cooper, who borrowed a gown, cap and smock to join the fine ladies in the throng. One of the waiters got drunk, put on a dress and also joined in. He was rumbled ‘and turned out of doors’, not because of his female attire but because he had not bought a ticket.

Princess Seraphina, meanwhile, appears to have danced or otherwise whiled the night away, the ‘night’ lasting until 5am.

However, Seraphina/John Cooper pops up the next month, July 1732, as the star of a rather different spectacle – in the courtroom at the Old Bailey.

This was a time, as the historian Rictor Norton writes, when sodomy was a hanging offence.

Ross Davies

By Rictor Norton

Masquerades flourished in London from the 1720s, and took place in assembly rooms, theatres, brothels, public gardens – and ‘molly houses’, or clubs where gay men gathered together. Some of the ‘mollies’ or ‘sodomites’ who frequented these disorderly pubs and coffee houses adopted female mannerisms, mimicking the voices of women, having bitch fights, and adopting ‘maiden’ nicknames for themselves, such as Pomegranate Molly, Primrose Mary (a butcher in Butcher Row), Dip-Candle Mary (a tallow chandler), Aunt England (a soap-boiler), Lady Godiva (a waiter), the Duchess of Gloucester (a butcher), and Black-eyed Leonora (a Drummer of the Guards).

Some of these men occasionally dressed as women, and sometimes, especially during the Christmas and New Year holiday period, private drag balls called ‘Festival Nights’ were held at the molly houses. For example, on 28 December 1725 a group of 25 men were apprehended in a molly house in Hart Street near Covent Garden and were arrested for dancing and misbehaving themselves, and they fought with the police officers while dressed in their masquerade habits. Some of these men had previously stood in the pillory for ‘assault with intent to commit sodomy’. In 1728 nine ‘male ladies’ were arrested at a private drag party at the Whitechapel home of Jonathan Muff, known as ‘Miss Muff’. The man who played the fiddle at these parties protested that ‘I only went to Muff’s house, to learn to play the violin’, but the jury did not believe him, and he was sentenced to death for sodomy. (While anal intercourse was a hanging offence, any other sort of sexual relations between men, including soliciting, was a misdemeanour punishable by up to two years in prison. Sex between women, though not strictly illegal, was viewed as abominable, and women disguised as men, including some women who married other women, were prosecuted for fraud and usually put in the pillory or flogged. There was no lesbian subculture, though there was a thriving gay male subculture, at least in London.)

Some of the molly houses were quasi-brothels, and had ‘Marrying Rooms’ where men engaged in mock ‘Wedding Nights’. Most of these were just part of the revelry, but some men entered into formal ‘marriages’ to mark long-term relationships. For example, in 1728 a molly wedding was celebrated in a molly pub in the Mint, run by a man nicknamed Sukey (Susan) Bevell. The two men who got married were nicknamed Hanover Kate and Queen Irons; they were attended by two men acting as bridesmaids, nicknamed Miss Kitten and Princess Seraphina; and guests at the wedding included a molly couple who were said to be ‘deeply in love’ with one another, nicknamed Madam Blackwell and St Dunstan’s Kate.

Though this wedding is described in a pamphlet by the street robber James Dalton and sounds like a satire, the men can be identified by examining court trials and newspaper accounts. Queen Irons was a recent French immigrant named John Hyons; his husband was a butcher named John Coleman. In late October 1726, both men had been convicted of assault with intent to commit sodomy with one another. They were sentenced to stand in the pillory, to pay a fine of 5 Marks, and to suffer three months’ imprisonment. After they got out of prison, they married one another, perhaps as an act of defiance as well as commitment. A bawdy song allegedly sung by Queen Irons had the refrain ‘Among our own selves we’ll be free’.

In the wedding party, St Dunstan’s Kate’s was a man named Powell who worked as a clerk at St Dunstan’s church; perhaps he was the one who performed the ceremony. The bridesmaid Miss Kitten was James Oviat; he was a member of James Dalton’s gang, who regularly blackmailed men after offering to have sex with them and then threatening to accuse them of sodomy. The other bridesmaid, Princess Seraphina, was John Cooper; he was an unemployed gentleman’s valet who earned money by prostitution, and by arranging meetings between sodomites. He went in drag to one of the very first open-air masquerade balls, a ridotto al fresco, given at Vauxhall Gardens on 21 June 1732.

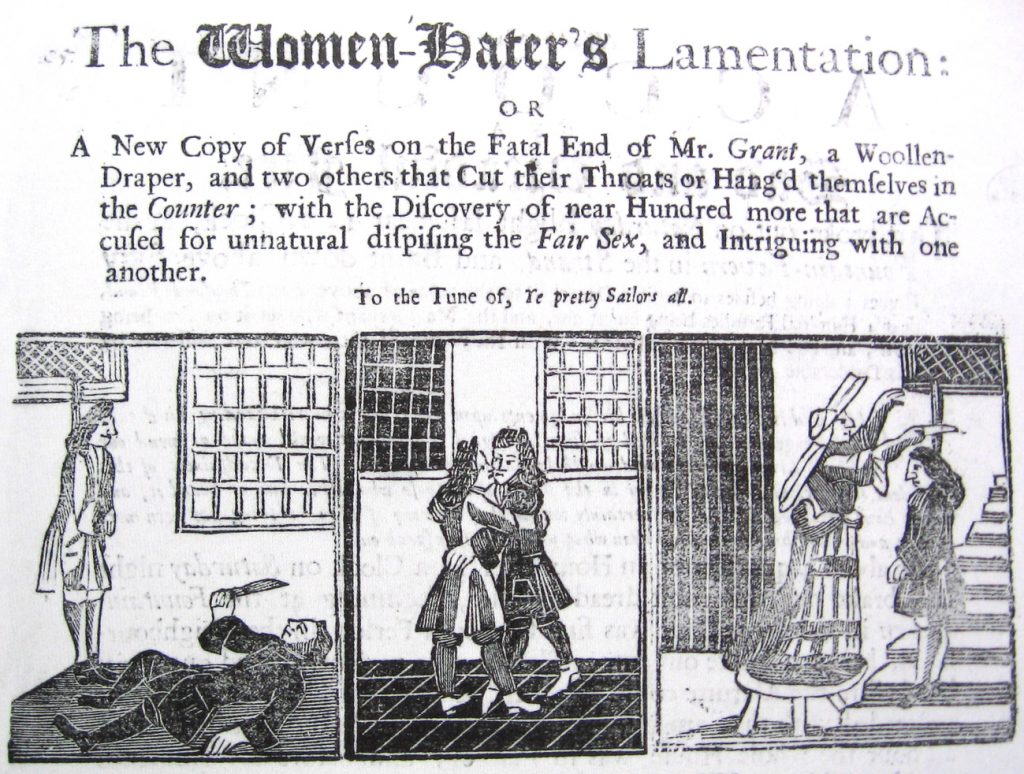

Several men committed suicide following a raid at a molly house near the Stock Exchange in London in 1707. From a broadside ballad, The Women-Hater’s Lamentation (1707). Image courtesy © Rictor Norton

As commercial masquerades became fashionable for the wider public, it is only to be expected that some gay men would have exploited their opportunities. Such masquerades were first organised by the impresario John James Heidegger at the Haymarket Theatre from 1717 onwards. His ‘Midnight Masquerades’ were tremendously successful, and drew 800 people a week. They provided many people with the opportunity to explore fetishism and transvestism. Men disguised themselves as witches, bawds, nursing maids and shepherdesses, while women dressed as hussars, sailors, cardinals and Mozartian boys. In the early days of the fashion, Richard Steele, co-founder of the early periodical The Tatler, went to one where a parson called him a ‘pretty fellow’ and tried to pick him up, and Horace Walpole, antiquarian and builder of Strawberry Hill, passed for an old woman at a masquerade in 1742. The opportunities for illicit assignations provoked a host of anti-masquerade satires, and some tracts attacked the mollies or sodomites who allegedly attended them, supposedly imitating infamous homosexual cross-dressers such as Sporus, Caligula, and Heliogabalus.

Legal records have given us some details of the life of ‘Princess Seraphina’, real name John Cooper, who appeared in court at the Old Bailey during the Sessions of 5–8 July 1732, when he prosecuted Thomas Gordon, an unemployed servant, for having assaulted him in Chelsea Fields and stealing his clothes and money on 30 May. This was the night of the Whit Monday holiday, when many people were out drinking and making merry. Cooper claimed that they met at a night cellar and drank three pints of hot beer together, then went for a morning walk as the weather was nice, and when they reached a secluded stand of trees Gordon took out a knife and forced Cooper to strip off his fine coat and waistcoat and breeches, and exchange them with Gordon’s dirty ragged shabby clothes. Gordon threatened that if Cooper charged him with robbery, he would swear Cooper was a sodomite and had given him the clothes to let him bugger Gordon. Cooper was furious at losing his fine clothes, and obtained a warrant for Gordon’s arrest at a brandy shop in Drury Lane. He brought the prosecution against him, which was a mistake, for not only did Gordon make the counter-charge that he had threatened to make, but a host of witnesses came forward to reveal that Cooper was not only a ‘molly cull’ but what we now call a ‘drag queen’ or perhaps even a ‘transgender’ individual.

A molly is put in the pillory for attempted sodomy in 1762. From a broadside ballad, Molly Exalted (1762). Image courtesy © Rictor Norton

At the trial, Mrs Holder, the landlady of the night cellar where they had drank their Huckle and Buff (that’s gin and ale made hot), said that Cooper frequently came to her cellar with Christopher (Kitt) Sandford, a tailor, and other mollies, and was a runner who carried messages between such gentlemen: ‘he’s one of them as you call Molly Culls, he gets his Bread that way; to my certain Knowledge he has got many a Crown under some Gentlemen, for going of sodomiting Errands’.

Jane Jones, a washerwoman, revealed that she had overheard Cooper and Gordon arguing in a pub, Cooper demanding his clothes back and threatening to accuse Gordon of robbery, Gordon saying he was entitled to the clothes and threatening to accuse Cooper of sodomy. She ended her testimony with the startling revelation that John Cooper was commonly known in the district as the ‘Princess Seraphina’. The judge was so taken aback that she had to repeat what she had just said, and one can imagine the jury suddenly becoming very attentive at this interesting turn of events. Her story was confirmed by Mary Poplet, the keeper of the Two Sugar Loaves public house in Drury Lane, who astonished the court with her testimony:

‘I have known her Highness a pretty while, she us’d to come to my House from Mr. Tull, to enquire after some Gentlemen of no very good Character; I have seen her several times in Women’s Cloaths, she commonly us’d to wear a white Gown, and a scarlet Cloak, with her Hair frizzled and curl’d all round her Forehead; and then she would so flutter her Fan, and make such fine Curt’sies, that you would not have known her from a Woman: She takes great Delight in Balls and Masquerades, and always chuses to appear at them in a Female Dress, that she may have the Satisfaction of dancing with fine Gentlemen. . . . I never heard that she had any other Name than the Princess Seraphina.’

Mary Ryler, one of the serving girls at the pub, said she knew the Princess very well, that he sometimes worked as a nurse, and that he dressed as a woman at ‘the last Masquerade, the Ridotto al Fresco at Vauxhall’. We can deduce the date of this event by examining contemporary newspaper reports. From late May, the very first Ridotto was advertised to take place on 7 June, which it duly did. It was intended for the Ridotto to be repeated two weeks later, on 21 June, perhaps for a less wealthy class of clientele, but on 12 June an advertisement announced a change in plans: ‘By the Desire of several Persons of Quality and Distinction. The Entertainment of the BALL or Ridotto Al’ Fresco, at Spring-Gardens, Vaux-Hall, will be alter’d on Wednesday the 21st Instant to an ASSEMBLY, where no Person will be admitted without Tickets, or with Swords or Masques. The Diversions will be after the Manner of Bath and Tunbridge Walks, with several Additions. The Doors will be opened at Seven, and the Supper-Room at Eleven.’ (Daily Advertiser, 12 June, repeated several times up to the event). Then the plan for the original Ridotto was reinstated. Here is an advertisement for it:

At Spring-Gardens,

Vaux-Hall, this Day, being Wednesday the 21st of June (instead of the Assembly already advertis’d) we are oblig’d to continue the Ball or A Ridotto Al Fresco with additional Diversions after the Manner of Bath and Tunbridge-Wells. Persons with Masques, but none with Swords, will be admitted. The Doors will be opened at Nine o’Clock, and the Supper-Room at Eleven. N.B. There will be no other Ridotto this Season. (Daily Advertiser, 21 June 1732)

The tickets were to cost one guinea. But the event of 21 June was not as successful as had been hoped:

Friday, June 23. On Wednesday night at the Ridotto al’ Fresco, at Faux Hall, there was not half the Company as was expected, being no more than two hundred and three persons, amongst whom were several persons of distinction, but more Ladies than Gentlemen; and the whole was managed with great order and decency, a detachment of one hundred of the Foot guards being posted round the garden. A waiter belonging to the house having got drunk, put on a dress, and went to Fresco with the rest of the company; but being discovered, he was immediately turned out of doors. His Royal highness the Prince, the E. of Scarborough, the L. Gage, &c. were present, and the whole affair was managed with decency and good order: about 2 o’clock his Royal Highness went away, but the greatest part of the company staid ’till 5 in the morning.’ (Grub-street Journal, 29 June 1732)

Considering that Cooper brought his prosecution case by 6 July, it is almost certain that it was this Ridotto of 21 June – the ‘last Masquerade’ of Mary Riler’s testimony – that he attended.

At the trial, Mary Robinson, a respectable lady, said that she and Cooper shared the same Mantua-makers [dress-makers] in the Strand. He once asked to borrow her suit of red damask because it ‘looked mighty pretty’; he wanted it to go to Mrs Green’s in Nottingham Court by the Seven Dials where he was to meet some fine gentlemen. Mrs Green occasionally lent him a velvet scarf and gold watch. Mary Robinson reported the Princess’s words to her: ‘Lord, Madam, I must ask your Pardon, I was at your Mantua-maker’s Yesterday, and dress’d my Head in your Lac’d Pinners, and I would fain have borrow’d them to have gone to the Ridotto at Vauxhall last Night, but I cou’d not persuade her to lend ’em me; but however she lent me your Callimanco Gown and Madam Nuttal’s Mob [cap], and one of her Smocks, and so I went thither to pick up some Gentlemen to Dance.’

A hand-coloured engraving of the Centre Cross Walk at Vauxhall Gardens, Edward Rooker (1724–1774). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

After the masquerade Mrs Robinson said ‘And did you make a good Hand of it, Princess?’ ‘No, Madam’, said Cooper, ‘I pick’d up two Men, who had no Money, but however they proved to be my old Acquaintance, and very good Gentlewomen they were. One of them has been transported for counterfeiting Masquerade Tickets; and t’other went to the Masquerade in a Velvet Domine, and pick’d up an old Gentleman, and went to Bed with him, but as soon as the old Fellow found that he had got a Man by his Side, he cry’d out, “Murder”.’

Cooper lived at No 11, Eagle Court, in the Strand, with Mr and Mrs Tull, whom he nursed through a salivation. He was their friend rather than a domestic servant; other lodgers were Mr Levit and Mr Sydney. The Princess was liked by all the women of his neighbourhood, and we can easily imagine him sitting down with them for a quiet cup of tea and a good gossip. The only person who disliked him was his cousin, a distiller in Wardour Street, who once gave him a shilling and told him to go about his business and not to scandalise the neighbours. Cooper’s prosecution of Gordon was really no more than a quarrel that had gotten out of control and could not be stopped once the wheels had been set in motion. He had nearly reached an agreement with Gordon to ‘make up the affair’, but he was egged on by two men who expected their share of the reward for capturing the supposed thief. Fortunately it had no disastrous consequences for either defendant or plaintiff; Gordon was acquitted as an honest working man, and no charges were brought against Cooper, alias Princess Seraphina.

Rictor Norton is the author of Mother Clap’s Molly House: The Gay Subculture in England 1700 –1830, and other books on eighteenth-century history and literature. The primary documents on which Rictor Norton bases this Vauxhall History article are on his online Sourcebook: Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England, rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/.

Rictor Norton is the author of Mother Clap’s Molly House: The Gay Subculture in England 1700 –1830, and other books on eighteenth-century history and literature. The primary documents on which Rictor Norton bases this Vauxhall History article are on his online Sourcebook: Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England, rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/.